Empowering Local Communities: Through

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-20-1908 Journal Publishing Company

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 12-20-1908 Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-20-1908 Journal Publishing Company Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_mj_news Recommended Citation Journal Publishing Company. "Albuquerque Morning Journal, 12-20-1908." (1908). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ abq_mj_news/3504 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Morning Journal 1908-1921 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' r ..r,........r., f. n ' ni i i, ,n Kw iiiinii m f ii l'W.i m i1 ..in .r, ..r). .r I f TWELVE PAGES. ALBUQUERQUE MOKNING J01JBNAL. THIRTIclH YfcAR. Vol. CXX, Mo. 81. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, SUNDAY, DECEMBER 20, Itjr Stall SO I. a Month. Single coplea, S ceuta. Ity Currier 60 cenia a- nxuitli. (if and mir ancestors in cmhoddiiug its Stock association, arrived in Los An- in the inn dm k w bib- ships iieod-pan- s sum-tilin- in tli" liill of rights in our geles toda.v to arrange for the twelfth i ii k minor are being docked in STANDARD OIL WANTS annual convention which will be held I'll ('id sill i eon In the outer docks. CHANCE FOR Ill conclusion it is urged lll.lt the TARIFF ill this city from January (1 to 2s REHEARING IS llv floating the inner caisson from 0 granting of tin- writ would tint lie The officers will arrange the speakei the drv dock, of greater length hel'ole the (invention These w ill in- than anv now ill existence ,r i lanned clude the best in California and als. -

Stories Matter: the Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature (Pp

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 480 339 CS 512 399 AUTHOR Fox, Dana L., Ed.; Short, Kathy G., Ed. TITLE Stories Matter: The Complexity of CulturalAuthenticity in Children's Literature. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana,IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-4744-5 PUB DATE 2003-00-00 NOTE 345p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers ofEnglish, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana,.IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 47445: $26.95members; $35.95 nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010).-- Collected Works General (020) -- Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Childrens Literature; *Cultural Context; ElementaryEducation; *Literary Criticism; *Multicultural Literature;Picture Books; Political Correctness; Story Telling IDENTIFIERS Trade Books ABSTRACT The controversial issue of cultural authenticity inchildren's literature resurfaces continually, always elicitingstrong emotions and a wide range of perspectives. This collection explores thecomplexity of this issue by highlighting important historical events, current debates, andnew questions and critiques. Articles in the collection are grouped under fivedifferent parts. Under Part I, The Sociopolitical Contexts of Cultural Authenticity, are the following articles: (1) "The Complexity of Cultural Authenticity in Children's Literature:Why the Debates Really Matter" (Kathy G. Short and Dana L. Fox); and (2)"Reframing the Debate about Cultural Authenticity" (Rudine Sims Bishop). Under Part II,The Perspectives of Authors, -

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Barbara UC Santa Barbara Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Navigating a Climate of Fear: Adolescent Arrivals and the Trump Era Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6pt4w2np Author Rodriguez, Liliana V Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Navigating a Climate of Fear: Adolescent Arrivals and the Trump Era A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Liliana V Rodriguez Committee in charge: Professor Edward E. Telles, Chair Professor Victor M. Rios Professor George Lipsitz Professor Néstor P. Rodríguez, University of Texas at Austin Professor Roberto G. Gonzales, Harvard University June 2019 The dissertation of Liliana V Rodriguez is approved. ____________________________________________ Roberto G. Gonzales ____________________________________________ Néstor P. Rodriguez ____________________________________________ George Lipsitz ____________________________________________ Victor M. Rios ____________________________________________ Edward E. Telles, Committee Chair June 2019 Navigating a Climate of Fear: Adolescent Arrivals and the Trump Era Copyright © 2019 by Liliana V Rodriguez iii DEDICATION With love to Jacey and Gianna Because of you I know there is hope for a better future iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This work could have not been completed without the gracious participation of the adolescent arrivals whose narratives form the life and breath of this study. I am forever grateful to each one of them for allowing me into their worlds and I hope my work does justice to their lived experiences. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Edward Telles, Victor Rios, George Lipsitz, Néstor Rodríguez, and Roberto Gonzales for believing in me. -

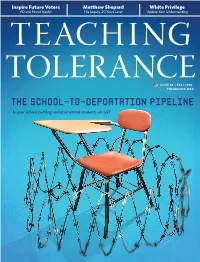

The School-To-Deportation Pipeline Is Your School Putting Undocumented Students at Risk?

Inspire Future Voters Matthew Shepard White Privilege PD and Poster Inside! His Legacy, Years Later Update Your Understanding TEACHING ISSUE | FALL TOLERANCETOLERANCE.ORG The School-to-Deportation Pipeline Is your school putting undocumented students at risk? TT60 Cover.indd 1 8/22/18 1:25 PM FREE WHAT CAN TOLERANCE. ORG DO FOR YOU? LEARNING PLANS GRADES K-12 EDUCATING FOR A DIVERSE DEMOCRACY Discover and develop world-class materials with a community of educators committed to diversity, equity and justice. You can now build and customize a FREE learning plan based on any Teaching Tolerance article! TEACH THIS Choose an article. Choose an essential question, tasks and strategies. Name, save and print your plan. Teach original TT content! TT60 TOC Editorial.indd 2 8/21/18 2:27 PM BRING SOCIAL JUSTICE WHAT CAN TOLERANCE. ORG DO FOR YOU? TO YOUR CLASSROOM. TRY OUR FILM KITS SELMA: THE BRIDGE TO THE BALLOT The true story of the students and teachers who fought to secure voting rights for African Americans in the South. Grades 6-12 Gerda Weissmann was 15 when the Nazis came for her. ONE SURVIVOR ey took all but her life. REMEMBERS Gerda Weissmann Klein’s account of surviving the ACADEMY AWARD® Holocaust encourages WINNER BEST DOCUMENTARY SHORT SUBJECT thoughtful classroom discussion about a A film by Kary Antholis l CO-PRODUCED BY THE UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM AND HOME BOX OFFICE di cult-to-teach topic. Grades 6-12 THE STORY of CÉSAR CHÁVEZ and a GREAT MOVEMENT for SOCIAL JUSTICE VIVA LA CAUSA MEETS CONTENT STANDARDS FOR SOCIAL STUDIES AND LANGUAGE VIVA LA CAUSA ARTS, GRADES 7-12. -

Write It in INK!, Perform There

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons February 2015 2-11-2015 The aiD ly Gamecock, Wednesday, February 11, 2015 University of South Carolina, Office oftude S nt Media Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_feb Recommended Citation University of South Carolina, Office of Student Media, "The aiD ly Gamecock, Wednesday, February 11, 2015" (2015). February. 8. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/gamecock_2015_feb/8 This Newspaper is brought to you by the 2015 at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in February by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH CAROLINA WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 11, 2015 VOL. 116, NO. 87 • SINCE 1908 Does SG serve its Head-to-Head purpose? | Page 6 David Roberts @DAVIDJAYROBERTS Thornwell ew teams in the Southeastern Conference have struggled as Fmightily as South Carolina, who beat Missouri 65-60 Tuesday night, has thus far. powers In fact, only Missouri has. The Tigers are dead last in SEC play and are now 0-5 in conference road games after their loss to South Gamecocks Carolina. The Gamecocks are not much better, however, as they sit in second- to-last place in the conference. past Tigers South Carolina had lost six of its last seven games entering Tuesday’s matchup, which caused head coach Frank Martin to challenge members of his team to step into leadership roles. “Leadership is who’s willing to stand up and embrace the moment,” Martin said Monday afternoon before the game. “Who’s willing to stand up in front of their peers and say, ‘Hey, enough of this. -

Fall 2016 Vol. 5 No. 1 Will There Really Be a Morning? Kerry Maloney….….……………….……………………………………..………………………………....2

Fall 2016 Vol. 5 No. 1 Will There Really Be A Morning? Kerry Maloney….….……………….……………………………………..………………………………....2 Harry Lyn Huff, 1952-2016. …………….………………..…………..………………………….………………………………………...……...4 Anti-Racist Pedagogies: A Reflection Tyler Schwaller….………………………………………………..…………………….……………….....5 The Mirror of Advent Regina L. Walton………………………………..………………..…………….…………………………...8 On Groping, Trump and Jesus Stephanie Paulsell…………………………………………………………………………………….....10 Bearing Witness at the Tomb: Being White in Trump’s America Wilson Hood………...……...…………………………….………………..…………………………….….12 Fierce defiance. Faithful memory. Mandi Rice…………………………………………………………………………..…………………………..14 This, I Think, is Ministry Dudley C. Rose………………………………………………..…….……………………………………....16 Religions and the Practice of Peace: A Student’s Perspective Jenna Alatriste………………………………………..……….……………….……………………...…..19 Prophetic Grief Sana Saeed……………………………………..…………………….……………………………………....20 With Faith and Hope: Somos Gente Que Lucha (“We Are People Who Struggle”) Alfredo Garcia……..…………………………………………………………..…….…………………....21 Unveiling the Stories of Dreamers at HDS Diana Ortiz Giron……..…………………………………………………………..…….…….………....24 Will There Really Be a Morning? Kerry Maloney HDS Chaplain and Director of Religious and Spiritual Life Will there really be a "Morning"? Is there such a thing as "Day"? Could I see it from the mountains If I were as tall as they? Has it feet like Water lilies? Has it feathers like a Bird? Does it come from famous places Of which I have never heard? Oh some Scholar! Oh some Sailor! -

Better Call Saul: Is You Want Discoverable Communications: the Misrepresentation of the Attorney-Client Privilege on Breaking Bad

Volume 45 Issue 2 Breaking Bad and the Law Spring 2015 Better Call Saul: Is You Want Discoverable Communications: The Misrepresentation of the Attorney-Client Privilege on Breaking Bad Armen Adzhemyan Susan M. Marcella Recommended Citation Armen Adzhemyan & Susan M. Marcella, Better Call Saul: Is You Want Discoverable Communications: The Misrepresentation of the Attorney-Client Privilege on Breaking Bad, 45 N.M. L. Rev. 477 (2015). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nmlr/vol45/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The University of New Mexico School of Law. For more information, please visit the New Mexico Law Review website: www.lawschool.unm.edu/nmlr \\jciprod01\productn\N\NMX\45-2\NMX208.txt unknown Seq: 1 12-MAY-15 12:16 “BETTER CALL SAUL” IF YOU WANT DISCOVERABLE COMMUNICATIONS: THE MISREPRESENTATION OF THE ATTORNEY- CLIENT PRIVILEGE ON BREAKING BAD Armen Adzhemyan and Susan M. Marcella* INTRODUCTION What if Breaking Bad had an alternate ending? One where the two lead characters and co-conspirators in a large methamphetamine cooking enterprise, Walter White and Jesse Pinkman,1 are called to answer for their crimes in a court of law. Lacking hard evidence and willing (i.e., * Armen Adzhemyan is a litigation associate in the Los Angeles office of Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP where he has researched and litigated numerous issues regarding the attorney-client privilege as a member of the Antitrust, Law Firm Defense, Securities Litigation, and Transnational Litigation Practice Groups. He received his J.D. in 2007 from the University of California, Berkeley School of Law, where he served as a senior editor on the Berkeley Journal of International Law. -

When They See Us – S01E04 – Part 4

Netflix Creative Distro CENTRAL PARK PART FOUR Written by Ava DuVernay & Michael Starrbury Story By Ava DuVernay SHOOTING DRAFT FULL WHITE 06.19.18 FULL BLUE 07.10.18 PINK PAGES 07.24.18 YELLOW PAGES 09.18.18 GREEN PAGES 10.03.18 2ND WHITE PAGES 10.17.18 2ND BLUE PAGES 10.24.18 CP5 - PART FOUR - FULL BLUE DRAFT 7.10.18 1. OVER BLACK COURT CLERK (PRE-LAP) In the matter of the state of New York vs. Korey Wise, as to the count of rape... 1 NetflixINT. GALLIGAN’S COCreativeURTROOM - KOREY’S TRI ALDistro - 1990 1 KOREY WISE, 16, stands behind the defendant’s table listening with a neutral expression. COLIN MOORE, Korey’s lawyer, has a hand on his shoulder. COURT CLERK ...Not guilty. The audience in the gallery cheers, but we don’t see them. We stay on Korey, slowly moving into his captivating eyes. He’s staring at the words “IN GOD WE TRUST” on the wall behind the judge, putting his fate in God’s hands. COURT CLERK (CONT’D) As to the count of assault in the first degree... guilty. Exasperation and incredulous groans from the gallery. Angry voices demand JUSTICE! Colin’s grip on Korey’s shoulder is tighter. Korey’s face twitches, trying to stay strong. He can hear himself breathing and his heart pounding over the cacophony of noises rattling in his head. A baby crying. A mother in anguish. A gavel banging. It’s all too much. He shuts his eyes to escape. It works. The noise stops. -

Super! Drama TV October 2020 ▶Programs Are Suspended for Equipment Maintenance on the 14Th from 1:00-7:00

Super! drama TV October 2020 ▶Programs are suspended for equipment maintenance on the 14th from 1:00-7:00. Note: #=serial number [J]=in Japanese [D]=in Danish 2020.09.28 2020.09.29 2020.10.01 2020.10.02 2020.10.03 2020.10.04 Mon Tue Thu Fri Sat Sun 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 STAR TREK: DEEP SPACE NINE 06:00 Season 7 Season 7 Season 7 Season 7 #18 #19 #20 #21 06:30 「TIL DEATH DO US PART」 「STRANGE BEDFELLOWS」 06:30 「THE CHANGING FACE OF EVIL」 「WHEN IT RAINS...」 06:30 07:00 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 07:00 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 07:00 07:00 CAPTAIN SCARLET AND THE 07:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 07:00 8 9 MYSTERONS GENERATION Season 6 #23「The Maternal Combustion」 #1「The Matrimonial Momentum」 #28「INFERNO」 #23 07:30 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 07:30 THE BIG BANG THEORY Season 07:30 07:30 JOE 90 「RIGHTFUL HEIR」 07:30 8 9 #28 #24「The Commitment Determination」 #2「The Separation Oscillation」 「CHILD OF THE SUN GOD」 08:00 08:00 THE SECRET SERVICE 08:00 THE SECRET SERVICE 08:00 08:00 ULTRAMAN towards the future 08:00 STAR TREK: THE NEXT 08:00 #7 #9 #4 [J] GENERATION Season 6 「RECALL TO SERVICE」 「THE DEADLY WHISPER」 「the survivalists」 #24 08:30 08:30 THE SECRET SERVICE 08:30 THE SECRET SERVICE 08:30 08:30 THUNDERBIRDS ARE GO Season 「SECOND CHANCES」 08:30 #8 #10 3 「ERRAND OF MERCY」 「THE CURE」 #10「DEEP WATER」 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:00 information[J] 09:00 information[J] 09:00 09:30 09:30 MACGYVER Season 2 09:30 THE BLACKLIST Season 7 09:30 09:30 HAPPY VALLEY Season 2 09:30 S.W.A.T. -

WAH YOU MA, 85, of Honolulu, Died March 31, 2000. Born in China

M WAH YOU MA, 85, of Honolulu, died March 31, 2000. Born in China. Survived by son, Pang Fai; daughters, Lily Young and Irene Lum; brother, Wah Ying; sisters, Siu Hing and Siu Han; seven grandchildren; eight great-grandchildren. Chinese Buddhist services 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. Wednesday at Diamond Head Mortuary. Burial to follow at Diamond Head Memorial Park. WILLIAM FELICIANO "COCONUT HAT" MABIDA SR., 72, of Pearl City, died April 14, 2000. Survived by wife, Marva; sons, William Jr. and Joseph; daughters, Rosemarie Dudley, Miriam Mabida, Jessica Mabida-Bridges and Jodi Horcajo; brothers, Daniel, Gilbert and Ernest; sisters, Hattie DeGuzman, Juanita Suyat and Flora Tano; 18 grandchildren. Visitation 9 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. Friday at Borthwick Mortuary, service 11 a.m.; burial 2 p.m. at Hawaiian Memorial Park. MARIA VICTORIA MACADANGDANG, 35, of Waipahu, died June 19, 2000. Born in Pasuquin, Ilocos Norte, Philippines. Survived by mother, Virginia; brothers, Bernard, Oscar, Stanley; grandparents. Visitation 6 to 9 p.m. Friday at St. Joseph Catholic Church, Waipahu; Mass 7 p.m. Visitation also 8 to 10 a.m. Saturday at Nu‘uanu Memorial Park Mortuary; burial to follow at Valley of the Temples Memorial Park. B. Sharon MacCluer, 59, of Pukalani, Maui, a reading teacher, died Friday, March 10,2000 in Maui Memorial Hospital. She was born in Martinez, Calif. She is survived by husband L. Douglas; mother Jessie B. Daraskavich; sons Mitchell S. and Daniel; daughters Tracy S. MacCluer and Holly E. Roper, and two grandchildren. Memorial service: 5:30 p.m. -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

GPO-CRECB-1953-Pt2-17-1.Pdf

1953 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- SENATE 2133 ar-e serving abroad in the Armed Forces of the consideration of their resolution No. 115 with MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSE United States, or who are employed abroad reference to the passage of H. R. 2843, pro by the United States Government; to the viding for the investigation in the Territory A message from the House of Repre Committee on the Judiciary. of Hawaii of the conservation, development, sentatives, by Mr. Maurer, its reading and utilization of water resources; to the clerk, announced that the House agreed Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. to the report of the committee of con MEMORIALS 98. By Mr. McDONOUGH: Petition of a ference on the disagreeing votes of the Under clause 3 of rule XXII, memo number of citizens of Los Angeles, Calif., two Houses on the amendments of the protesting against any move to extend the rials were presented and referred as fol draft and favoring universal military train· Senate to the bill <H. R. 3053) making , lows: ing; to the Committee on Armed Services. supplemental appropriations for the By the SPEAKER: Memorial of the Legis 99. By Mrs. ROGERS of Massachusetts: fiscal year ending June 30, 1953, and for lature of the State of Arizona, memorializing Petition of the City Council, Lowell, Mass., other purposes; that the House receded the President and the Congress of the United asking that Congress take action to extend from its disagreement to the amend States relative to their house joint memorial the authorization for the Federal Govern ments of the Senate numbered 2, 6, 8, No.5, requesting the establishment of an ad ment to control rents in Lowell; to the Com· 10, 12, 16, 18, 19,20, 25, 30, 31,32,and42 ditional International Gate at Nogales, mittee ·on Banking and Currency.