Materials for the 2013 Summer Candidacy Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

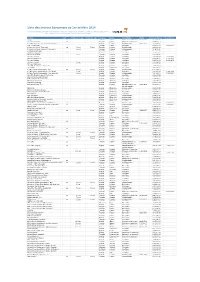

Liste Des Sources Europresse Au 1Er Octobre 2016

Liste des sources Europresse au 1er octobre 2016 Document confidentiel, liste sujette à changement, les embargos sont imposés par les éditeurs, le catalogue intégral est disponible en ligne : www.europresse.com puis "sources" et "nos sources en un clin d'œil" Source Pdf Embargo texte Embargo pdf Langue Pays Périodicité ISSN Début archives Fin archives 01 net oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 1276-519X 2005/01/10 01 net - Hors-série oui Français France Mensuel ou bimensuel 2014/04/01 100 Mile House Free Press (South Cariboo) Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 0843-0403 2008/04/09 18h, Le (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/04 2014/02/18 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) oui 7 jours 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2013/04/09 2 Rives, Les (Sorel-Tracy, QC) (site web) 7 jours Français Canada Hebdomadaire 2004/01/06 20 Minutes (site web) Français France Quotidien 2006/01/30 24 Heures (Suisse) oui Français Suisse Quotidien 2005/07/07 24 heures Montréal 1 jour Français Canada Quotidien 2012/04/04 24 hours Calgary Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Edmonton Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 2013/08/02 24 hours Ottawa Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/02 2013/08/02 24 hours Toronto 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 hours Vancouver 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/04/05 24 x 7 News (Bahrain) (web site) Anglais Bahreïn Quotidien 2016/09/04 3BL Media Anglais États-Unis En continu 2013/08/23 40-Mile County Commentator, The oui 7 jours 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2001/09/04 40-Mile County Commentator, The (blogs) 1 jour Anglais Canada Quotidien 2012/05/08 2016/05/31 40-Mile County Commentator, The (web site) 7 jours Anglais Canada Hebdomadaire 2011/03/02 2016/05/31 98.5 FM (Montréal, QC) (réf. -

Not for Immediate Release

Contact: Name Dan Gaydou Email [email protected] Phone 616-222-5818 DIGITAL NEWS AND INFORMATION COMPANY, MLIVE MEDIA GROUP ANNOUNCED TODAY New Company to Serve Communities Across Michigan with Innovative Digital and Print Media Products. Key Support Services to be provided by Advance Central Services Michigan. Grand Rapids, Michigan – Nov. 2, 2011 – Two new companies – MLive Media Group and Advance Central Services Michigan – will take over the operations of Booth Newspapers and MLive.com, it was announced today by Dan Gaydou, president of MLive Media Group. The Michigan-based entities, which will begin operating on February 2, 2012, will serve the changing news and information needs of communities across Michigan. MLive Media Group will be a digital-first media company that encompasses all content, sales and marketing operations for its digital and print properties in Michigan, including all current newspapers (The Grand Rapids Press, The Muskegon Chronicle, The Jackson Citizen Patriot, The Flint Journal, The Bay City Times, The Saginaw News, Kalamazoo Gazette, AnnArbor.com, Advance Weeklies) and the MLive.com and AnnArbor.com web sites. “The news and advertising landscape is changing fast, but we are well-positioned to use our talented team and our long record of journalistic excellence to create a dynamic, competitive, digitally oriented news operation,” Gaydou said. “We will be highly responsive to the changing needs of our audiences, and deliver effective options for our advertisers and business partners. We are excited about our future and confident this new company will allow us to provide superior news coverage to our readers – online, on their phone or tablet, and in print. -

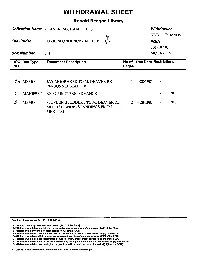

APRIL 1981 :Ii FOIA Fol-107/01 Box Number 7618 MCCARTIN 10 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages

WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name DEAVER, MICHAEL: FILES Withdrawer KDB 7/18/2005 File Folder CORRESPONDENCE-APRIL 1981 :ii FOIA FOl-107/01 Box Number 7618 MCCARTIN 10 DOC Doc Type Document Description No of Doc Date Restrictions NO Pages i) MEMO JAY MOORHEAD TO M. DEAVER RE 1 4/28/1981 B6 PERSONNEL MATTER 2 MANIFEST RE SUMMIT PRE-ADVANCE 1 B6 B7(C) I®\ MEMO STEPHEN STUDDERT TOM. DEAVER RE 2 4/28/1981 B2 B7(E) MUTUAL UNDERSTANDINGS FROM MEETING Freedom of Information Act· [5 U.S.C. 552(b)) B·1 National security classified Information [(b)(1) of the FOIA] B-2 Release would disclose Internal personnel rules and practices of an agency [(b)(2) of the FOIA] B-3 Release would violate a Federal statute [(b)(3) of the FOIA] B-4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential or financial Information [(b)(4) of the FOIA] B-6 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy [(b)(6) of the FOIA] B-7 Release would disclose information compiled for law enforcement purposes [(b)(7) of the FOIA] B-8 Release would disclose Information concerning the regulation of financial Institutions [(b)(B) of the FOIA] B-9 Release would disclose geological or geophysical Information concerning wells [(b)(9) of the FOIA] C. Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in donor's deed of gift. THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON April 28, 1981 l - ;". Dear Mr. Epple: Thank you for your kind letter and ex pression of continued support of President Reagan and his staff. -

A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2006 Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language Michael Alan Glassco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Glassco, Michael Alan, "Democracy, Hegemony, and Consent: A Critical Ideological Analysis of Mass Mediated Language" (2006). Master's Theses. 4187. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/4187 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DEMOCRACY, HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIA TED LANGUAGE by Michael Alan Glassco A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College in partial fulfillment'of the requirements for the Degreeof Master of Arts School of Communication WesternMichigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2006 © 2006 Michael Alan Glassco· DEMOCRACY,HEGEMONY, AND CONSENT: A CRITICAL IDEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF MASS MEDIATED LANGUAGE Michael Alan Glassco, M.A. WesternMichigan University, 2006 Accepting and incorporating mediated political discourse into our everyday lives without conscious attention to the language used perpetuates the underlying ideological assumptions of power guiding such discourse. The consequences of such overreaching power are manifestin the public sphere as a hegemonic system in which freemarket capitalism is portrayed as democratic and necessaryto serve the needs of the public. This thesis focusesspecifically on two versions of the Society of ProfessionalJournalist Codes of Ethics 1987 and 1996, thought to influencethe output of news organizations. -

DETROIT-METRO REGION Detroit News Submit Your Letter At: Http

DETROIT-METRO REGION Press and Guide (Dearborn) Email your letter to: Detroit News [email protected] Submit your letter at: http://content- static.detroitnews.com/submissions/letters/s Livonia Observer ubmit.htm Email your letter to: liv- [email protected] Detroit Free Press Email your letter to: [email protected] Plymouth Observer Email your letter to: liv- Detroit Metro Times [email protected] Email your letter to: [email protected] The Telegram Newspaper (Ecorse) Gazette Email your letter to: Email your letter to: [email protected] [email protected] Belleville Area Independent The South End Submit your letter at: Email your letter to: [email protected] http://bellevilleareaindependent.com/contact -us/ Deadline Detroit Email your letter to: Oakland County: [email protected] Birmingham-Bloomfield Eagle, Farmington Wayne County: Press, Rochester Post, Troy Times, West Bloomfield Beacon Dearborn Heights Time Herald/Down River Email your letter to: Sunday Times [email protected] Submit your letter to: http://downriversundaytimes.com/letter-to- Royal Oak Review, Southfield Sun, the-editor/ Woodward Talk Email your letter to: [email protected] The News-Herald Email your letter to: Daily Tribune (Royal Oak) [email protected] Post your letter to this website: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQL Grosse Pointe Times SfyWhN9s445MdJGt2xv3yyaFv9JxbnzWfC Email your letter to: [email protected] OLv9tDeuu3Ipmgw/viewform?c=0&w=1 Grosse Pointe News Lake Orion Review Email your -

Law and the Emerging Profession of Photography in the Nineteenth-Century United States

Photography Distinguishes Itself: Law and the Emerging Profession of Photography in the Nineteenth-Century United States Lynn Berger Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Lynn Berger All rights reserved ABSTRACT Photography Distinguishes Itself: Law and the Emerging Profession of Photography in the 19th Century United States Lynn Berger This dissertation examines the role of the law in the development of photography in nineteenth century America, both as a technology and as a profession. My central thesis is that the social construction of technology and the definition of the photographic profession were interrelated processes, in which legislation and litigation were key factors: I investigate this thesis through three case studies that each deal with a (legal) controversy surrounding the new medium of photography in the second half of the nineteenth century. Section 1, “Peer Production” at Mid-Century, examines the role of another relatively new medium in the nineteenth century – the periodical press – in forming, defining, and sustaining a nation-wide community of photographers, a community of practice. It argues that photography was in some ways similar to what we would today recognize as a “peer produced” technology, and that the photographic trade press, which first emerged in the early 1850s, was instrumental in fostering knowledge sharing and open innovation among photographers. It also, from time to time, served as a site for activism, as I show in a case study of the organized resistance against James A. -

Michael T. Nygard — «Release It! Design and Deploy Production-Ready Software

What readers are saying about Release It! Agile development emphasizes delivering production-ready code every iteration. This book finally lays out exactly what this really means for critical systems today. You have a winner here. Tom Poppendieck Poppendieck.LLC It’s brilliant. Absolutely awesome. This book would’ve saved [Really Big Company] hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars in a recent release. Jared Richardson Agile Artisans, Inc. Beware! This excellent package of experience, insights, and patterns has the potential to highlight all the mistakes you didn’t know you have already made. Rejoice! Michael gives you recipes of how you redeem yourself right now. An invaluable addition to your Pragmatic bookshelf. Arun Batchu Enterprise Architect, netrii LLC Release It! Design and Deploy Production-Ready Software Michael T. Nygard The Pragmatic Bookshelf Raleigh, North Carolina Dallas, Texas Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their prod- ucts are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters or in all capitals. The Pragmatic Starter Kit, The Pragmatic Programmer, Pragmatic Programming, Pragmatic Bookshelf and the linking g device are trademarks of The Pragmatic Programmers, LLC. Every precaution was taken in the preparation of this book. However, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages that may result from the use of information (including program listings) contained herein. Our Pragmatic courses, workshops, and other products can help you and your team create better software and have more fun. -

Ad Pages Template

INCREASING OUR ALCOHOL TOLERANCE SINCE 1992 VOLUME 25 | ISSUE 48 | DECEMBER 1-7, 2016 | FREE HHealthealth IInsurancensurance vvs.s. PPenalty.enallttyy.. healthyheaallltthy cchoice.hoiicce. IIff youyou ddon’ton’t hhaveaavve hhealthealltth iinsurance,nsurance, yyouou ccouldould eendnd uupp payingpaayying eextraxtra mmoneyoney iinn ttaxax ppenalties,enalltties, whilewhile gettinggetting nnothingothing iinn rreturn.eturn. ButBut itit doesn’tdoesn’t havehaavve toto bebe tthathaatt wway.aayy. VisitVViisit bbeWellnm.comeeWWWeellnm.com andand browsebrowse a varietyvariety ofof hhealthealltth insuranceinsurance choices.choices. SomeSome mmayaayy costcost almostalmost thethe samesame asas payingpaayying thethe taxtaaxx ppenalty.enalltty. InIn fact,ffaact, somesome ppeopleeople areare payingpaayyyiing betweenbetween $50$50 andand $100$100 perper month.month. And,And, iinsteadnstead ofof gettinggetting nothing,nothing, youyou ccanan bebe coveredcovered ffoforoorr eeverythingverything fromffrrom preventativeprevennttaattiivve carecare ttoo peacepeace ofof mmind.ind. Real Life: The Chavez Family WithWith InsuranceInsurance WWiWithoutithouutt IInsurancensurance • PreventivePreventive CareCare • PrescriptionsPrescriptions • NONO benefitsbenefits • DDoctoroctor VVisitsisits • HHospitalospital sstaystays • NNOO ccoverageoverage • PPeaceeace ooff mmindind • SSpecialistpecialist visitsvisits • NNOO ppeaceeace ooff mmindind & ssoo mmuchuch mmore!ore! • HHigherigher PPricetagricetag Annual Cost: $2,053 Annual Cost: $2,085 ForFor ffullull ccoverageoverage JustJJuust -

Media Kit September 2019

MEDIA KIT SEPTEMBER 2019 95+ YEARS OF CLIENT STORYTELLING. SMARTER MARKETING. LOCAL PRESENCE. NATIONAL REACH. MLive Media Group www.mlivemediagroup.com [email protected] 800.878.1400 20190911 Table Of Contents ABOUT US ....................................................................................................3 NATIONAL REACH ............................................................................... 4 MARKETING STRATEGISTS ............................................................5 CAPABILITIES........................................................................................... 6 DIGITAL SOLUTIONS .......................................................................... 8 TECH STACK ............................................................................................. 9 MLIVE.COM .............................................................................................. 10 PRINT SOLUTIONS ...............................................................................11 PRINT ADVERTISING ........................................................................12 INSERT ADVERTISING ......................................................................13 NEWSPAPER DISTRIBUTION MAP ...................................... 14 MICHIGAN’S BEST ...............................................................................15 CLIENTS RECEIVE ................................................................................17 TESTIMONIALS .................................................................................... -

December 4, 2017 the Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washi

December 4, 2017 The Hon. Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary United States Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Re: Uncoated Groundwood Paper from Canada, Inv. Nos. C–122–862 and A-122-861 Dear Secretary Ross: On behalf of the thousands of employees working at the more than 1,100 newspapers that we publish in cities and towns across the United States, we urge you to heavily scrutinize the antidumping and countervailing duty petitions filed by North Pacific Paper Company (NORPAC) regarding uncoated groundwood paper from Canada, the paper used in newspaper production. We believe that these cases do not warrant the imposition of duties, which would have a very severe impact on our industry and many communities across the United States. NORPAC’s petitions are based on incorrect assessments of a changing market, and appear to be driven by the short-term investment strategies of the company’s hedge fund owners. The stated objectives of the petitions are flatly inconsistent with the views of the broader paper industry in the United States. The print newspaper industry has experienced an unprecedented decline for more than a decade as readers switch to digital media. Print subscriptions have declined more than 30 percent in the last ten years. Although newspapers have successfully increased digital readership, online advertising has proven to be much less lucrative than print advertising. As a result, newspapers have struggled to replace print revenue with online revenue, and print advertising continues to be the primary revenue source for local journalism. If Canadian imports of uncoated groundwood paper are subject to duties, prices in the whole newsprint market will be shocked and our supply chains will suffer. -

The Center for the Study of Firearms and Public Policy Was Established in 1988 by the Second Amendment Foundation

CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF FIREARMS & PUBLIC POLICY A PROJECT OF SECOND AMENDMENT FOUNDATION The Center for the Study of Firearms and Public Policy was established in 1988 by the Second Amendment Foundation. Its primary purpose was to publish The Journal on Firearms and Public Policy The goal of this project was to expand the audience who had access to legal, economic, historical and other scholarly research about the Second Amendment. This year’s publication is the 25th Journal on Firearms and Public Policy. Dr. Edward F. Leddy, who was one of the prime movers behind the Journal served as editor for the first four issues. In 1993, Julianne Versnel assumed the role of editor for one year before becoming its Publisher. David B. Kopel, J.D. became its editor in 1994. In 2011, Dr. Gary Mauser became the editor. It has been the Second Amendment Foundation’s privilege to distribute over 100,000 print copies of the Journal on Firearms and Public Policy as well as offer significant access to them electronically over the years. The authors who have so generously provided the Journal on Firearms and Public Policy with their work are listed with their articles in the following pages. All Journals are available on www.saf.org as PDFs. State Constitutions: The Right to Bear Arms State Constitutions The Right of the Individual to Bear Arms David I. Caplan The Bill of Rights and the Military Earl Warren Standing Armies and Armed Citizens Roy G. Weatherup Historical Development and Subsequent Erosion James B. Whisker The Right to Bear Arms John Levin The Federalist Papers Alexander Hamilton/ James Madison Can the Second Amendment Survive Ashley Halsey Jr. -

The Irregular Musings of Lou Montulli: the Reasoning Behind Web Cookies

1/25/2018 The irregular musings of Lou Montulli: The reasoning behind Web Cookies The irregular musings of Lou Montulli Early web guy, engineer and entrepreneur TUESDAY, MAY 14, 2013 BLOG ARCHIVE ► 2015 (1) The reasoning behind Web Cookies ► 2014 (2) I get a fair number of questions about cookies from ▼ 2013 (15) individuals and the press. I thought I would try and ► June (5) explain some of the motivation and history behind Web ▼ May (10) cookies as well as some of the design behind them. Value based home music recording Feel free to post more questions and I will try and expand this article with more details. Wow, Flickr is giving away 1TB of storage for pers... See my recent post on 3rd party cookies as well! It's the end of <blink>! Why blocking 3rd party cookies could be a bad thin... Google "Play All" music service initial Motivation review HTTP is the networking language behind your browser. HTTP, or Hyper Text The reasoning behind Web Cookies Transport Protocol, was designed and introduced as part of the WWW project that started with Tim BernersLee at CERN and was expanded upon by several universities, A short history of the "about:" URL corporations and private individuals. The WWW and HTTP are open standards which The origins of the <blink> tag are published and given into the public trust in order to foster interoperability and to I'm trying out blogger create products that can become ubiquitous. Fine cabinetry meets not so modern gaming One of the problems faced in the early years of the web was how to create websites that had "memory" for individual users.