Predicting Retrosynthetic Pathways Using a Combined Linguistic Model and Hyper-Graph Exploration Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry

Philosophy of Science and Philosophy of Chemistry Jaap van Brakel Abstract: In this paper I assess the relation between philosophy of chemistry and (general) philosophy of science, focusing on those themes in the philoso- phy of chemistry that may bring about major revisions or extensions of cur- rent philosophy of science. Three themes can claim to make a unique contri- bution to philosophy of science: first, the variety of materials in the (natural and artificial) world; second, extending the world by making new stuff; and, third, specific features of the relations between chemistry and physics. Keywords : philosophy of science, philosophy of chemistry, interdiscourse relations, making stuff, variety of substances . 1. Introduction Chemistry is unique and distinguishes itself from all other sciences, with respect to three broad issues: • A (variety of) stuff perspective, requiring conceptual analysis of the notion of stuff or material (Sections 4 and 5). • A making stuff perspective: the transformation of stuff by chemical reaction or phase transition (Section 6). • The pivotal role of the relations between chemistry and physics in connection with the question how everything fits together (Section 7). All themes in the philosophy of chemistry can be classified in one of these three clusters or make contributions to general philosophy of science that, as yet , are not particularly different from similar contributions from other sci- ences (Section 3). I do not exclude the possibility of there being more than three clusters of philosophical issues unique to philosophy of chemistry, but I am not aware of any as yet. Moreover, highlighting the issues discussed in Sections 5-7 does not mean that issues reviewed in Section 3 are less im- portant in revising the philosophy of science. -

Peptide Chemistry up to Its Present State

Appendix In this Appendix biographical sketches are compiled of many scientists who have made notable contributions to the development of peptide chemistry up to its present state. We have tried to consider names mainly connected with important events during the earlier periods of peptide history, but could not include all authors mentioned in the text of this book. This is particularly true for the more recent decades when the number of peptide chemists and biologists increased to such an extent that their enumeration would have gone beyond the scope of this Appendix. 250 Appendix Plate 8. Emil Abderhalden (1877-1950), Photo Plate 9. S. Akabori Leopoldina, Halle J Plate 10. Ernst Bayer Plate 11. Karel Blaha (1926-1988) Appendix 251 Plate 12. Max Brenner Plate 13. Hans Brockmann (1903-1988) Plate 14. Victor Bruckner (1900- 1980) Plate 15. Pehr V. Edman (1916- 1977) 252 Appendix Plate 16. Lyman C. Craig (1906-1974) Plate 17. Vittorio Erspamer Plate 18. Joseph S. Fruton, Biochemist and Historian Appendix 253 Plate 19. Rolf Geiger (1923-1988) Plate 20. Wolfgang Konig Plate 21. Dorothy Hodgkins Plate. 22. Franz Hofmeister (1850-1922), (Fischer, biograph. Lexikon) 254 Appendix Plate 23. The picture shows the late Professor 1.E. Jorpes (r.j and Professor V. Mutt during their favorite pastime in the archipelago on the Baltic near Stockholm Plate 24. Ephraim Katchalski (Katzir) Plate 25. Abraham Patchornik Appendix 255 Plate 26. P.G. Katsoyannis Plate 27. George W. Kenner (1922-1978) Plate 28. Edger Lederer (1908- 1988) Plate 29. Hennann Leuchs (1879-1945) 256 Appendix Plate 30. Choh Hao Li (1913-1987) Plate 31. -

Lecture 1: Strategies and Tactics in Organic Synthesis

Massachusetts Institute of Technology Organic Chemistry 5.511 October 3, 2007 Prof. Rick L. Danheiser Lecture 1: Strategies and Tactics in Organic Synthesis Retrosynthetic Analysis The key to the design of efficient syntheses ". the grand thing is to be able to reason backwards. That is a very useful accomplishment, and a very easy "The end is where we start from...." one, but people do not practice it much." T. S. Eliot, in "The Four Quartets" Sherlock Holmes, in "A Study in Scarlet" Strategy Tactics overall plan to achieve the means by which plan ultimate synthetic target is implemented intellectual experimental retrosynthetic planning synthetic execution TRANSFORMS REACTIONS Target Precursor Precursor Target Definitions Retron Structural unit that signals the application of a particular strategy algorithm during retrosynthetic analysis. Transform Imaginary retrosynthetic operation transforming a target molecule into a precursor molecule in a manner such that bond(s) can be reformed (or cleaved) by known or reasonable synthetic reactions. Strategy Algorithm Step-by-step instructions for performing a retrosynthetic operation. "...even in the earliest stages of the process of simplification of a synthetic problem, the chemist must make use of a particular form of analysis which depends on the interplay between structural features that exist in the target molecule and the types of reactions or synthetic operations available from organic chemistry for the modification or assemblage of structural units. The synthetic chemist has learned by experience to recognize within a target molecule certain units which can be synthesized, modified, or joined by known or conceivable synthetic operations...it is convenient to have a term for such units; the term "synthon" is suggested. -

![[2.2]Paracyclophanes- Structure and Reactivity Studies Von Der](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2287/2-2-paracyclophanes-structure-and-reactivity-studies-von-der-1602287.webp)

[2.2]Paracyclophanes- Structure and Reactivity Studies Von Der

Syntheses of Functionalised [2.2]Paracyclophanes- Structure and Reactivity Studies Von der Gemeinsamen Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Technischen Universität Carolo Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr.rer.nat.) genehmigte D i s s e r t a t i o n von Swaminathan Vijay Narayanan aus Chennai (Madras) / India 1. Referent: Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. Henning Hopf 2. Referentin: Prof. Dr. Monika Mazik eingereicht am: 20. Jan 2005 mündliche Prüfung (Disputation) am: 29. März 2005 Druckjahr 2005 Vorveröffentlichungen der Dissertation Teilergebnisse aus dieser Arbeit wurden mit Genehmigung der Gemeinsamen Naturwissenschaft-lichen Fakultät, vertreten durch die Mentorin oder den Mentor/die Betreuerin oder den Betreuer der Arbeit, in folgenden Beiträgen vorab veröffentlicht: Publikationen K. El Shaieb, V. Narayanan, H. Hopf, I. Dix, A. Fischer, P. G. Jones, L. Ernst & K. Ibrom.: 4,15-Diamino[2.2]paracyclophane as a starting material for pseudo-geminally substituted [2.2]paracyclophanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem.: 567-577 (2003). Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde in der Zeit von Oktober 2001 bis Januar 2004 am Institut für Organische Chemie der Technischen Universität Braunschweig unter der Leitung von Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Henning Hopf angefertigt. It is my great pleasure to express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. Henning Hopf for his support, encouragement and guidance throughout this research work. I thank him a lot for his invaluable ideas and remarks which made this study very interesting. I admire deep from my heart his energetic way of working and his brilliant ideas which made possible this research work to cover a vast area. -

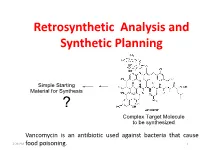

Retrosynthetic Analysis and Synthetic Planning

Retrosynthetic Analysis and Synthetic Planning Vancomycin is an antibiotic used against bacteria that cause 2:24 PM food poisoning. 1 Life’s Perspectives Planning a Journey to the Unknown 2:24 PM 2 Retrosynthetic Analysis Definition Retrosynthetic analysis (retrosynthesis) is a technique for planning a synthesis, especially of complex organic molecules, whereby the complex target molecule (TM) is reduced into a sequence of progressively simpler structures along a pathway which ultimately leads to the identification of a simple or commercially available starting material (SM) from which a chemical synthesis can then be developed. Retrosynthetic analysis is based on known reactions (e.g the Wittig reaction, oxidation, reduction etc). The synthetic plan generated from the retrosynthetic analysis will be the roadmap to guide the synthesis of the target molecule. 2:24 PM 3 Synthetic Planning Definition Synthesis is a construction process that involves converting simple or commercially available molecules into complex molecules using specific reagents associated with known reactions in the retrosynthetic scheme. Syntheses can be grouped into two broad categories: (i) Linear syntheses 2:24 PM (ii)Convergent syntheses 4 Linear Synthesis Definition In linear synthesis, the target molecule is synthesized through a series of linear transformations. Since the overall yield of the synthesis is based on the single longest route to the target molecule, by being long, a linear synthesis suffers a lower overall yield. The linear synthesis is fraught with failure for its lack of flexibility leading to potential large losses in the material already invested in the synthesis at the time of failure. 2:24 PM 5 Convergent Synthesis Definition In convergent synthesis, key fragments of the target molecule are synthesized separately or independently and then brought together at a later stage in the synthesis to make the target molecule. -

12.1 One-Step Syntheses

12.1 One‐Step Syntheses 12.1 One‐Step Syntheses • When building a HOME, you must have the right tools, • You may be able to solve one‐step syntheses by but you also need to know HOW to use the tools. matching the reaction pattern with an example in the • When building a MOLECULE (designing a synthesis), a textbook. lot of tools are available. Where are they? – To add Br–Br across a C=C double bond, an alkene is generally treated with Br / CCl in the dark. • To optimize your synthesis, you must understand HOW 2 4 the tools work. WHY? • How do you solve such syntheses without the textbook and without having to memorize each set of reagents? • What tools (reagents and conditions) are needed for – Learning to use any tool requires PRACTICE. the synthesis below? – Its also helpful to know mechanisms. WHY? Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 12 -1 Klein, Organic Chemistry 1e Copyright 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 12 -2 Klein, Organic Chemistry 1e 12.2 Functional Group 12.1 One‐Step Syntheses Transformations • Solving one‐step syntheses: • Let’s review some synthetic tools we have learned so 1. Analyze the structures of the reactant and product. far. 2. Assess HOW the functional groups have changed. • In Chapter 9, we learned how to shift the position of a 3. Use the reactions and mechanisms you have learned to halide. determine appropriate reagents and conditions. 4. Check your answer by working out the mechanism. • Solve the synthesis. • The regiochemical considerations in this process are • Practice with CONCEPTUAL CHECKPOINTs vital to making the correct product. -

The Origins of Nucleotides.Pdf

1956 SYNPACTS The Origins of Nucleotides TheMatthew Origins of Nucleotides W. Powner,*a John D. Sutherland,b Jack W. Szostaka a Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and Department of Molecular Biology and Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, 185 Cambridge Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02114, USA Fax +1(617)6433328; E-mail: [email protected] b MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0QH, UK Received 18 April 2011 This paper is dedicated to the memory of Leslie Orgel, a greatly missed colleague and a true pioneer of prebiotic chemistry Abstract: The origins of life represent one of the most fundamental chemical questions being addressed by modern science. One of the longstanding mysteries of this field is what series of chemical reac- tions could lead to the molecular biologists dream; a pool of homo- chiral nucleotides? Here we summarize those results we consider to be historically important and outline our recently published re- search aimed at understanding the chemoselective origins of the canonical ribonucleotides. 1 Introduction 1.1 Nucleotides: What’s the Problem? 2 Synthesis of Activated Pyrimidines Matthew W. Powner (left) obtained his MChem in chemistry at the 2.1 Pyrimidine Elaboration by Cyanovinylation University of Manchester, and also his PhD in organic chemistry wor- 2.2 Photochemical Epimerization and Cytidine to Uridine king with Prof. John. D. Sutherland. He continued his research at Conversion Manchester as an EPSRC PhD plus fellow, before moving to the la- 2.3 Urea-Mediated Phosphoryl Transfer and Intramolecular boratory of Prof. Jack Szostak as postdoctoral fellow at Harvard Me- Rearrangement dical School and Massachusetts General Hospital. -

A Retrosynthetic Analysis Algorithm Implementation Ian A

Watson et al. J Cheminform (2019) 11:1 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13321-018-0323-6 Journal of Cheminformatics SOFTWARE Open Access A retrosynthetic analysis algorithm implementation Ian A. Watson, Jibo Wang and Christos A. Nicolaou* Abstract The need for synthetic route design arises frequently in discovery-oriented chemistry organizations. While traditionally fnding solutions to this problem has been the domain of human experts, several computational approaches, aided by the algorithmic advances and the availability of large reaction collections, have recently been reported. Herein we present our own implementation of a retrosynthetic analysis method and demonstrate its capabilities in an attempt to identify synthetic routes for a collection of approved drugs. Our results indicate that the method, leveraging on reaction transformation rules learned from a large patent reaction dataset, can identify multiple theoretically feasible synthetic routes and, thus, support research chemist everyday eforts. Keywords: Retrosynthetic analysis, Chemical synthesis, Synthetic route design, Reaction informatics Introduction In a typical RA scenario, given a target chemical struc- Research needs for chemical synthesis predictability, ture, the process initiates a recursive decomposition loop synthetic route planning and reaction optimization has using available synthetic knowledge. In each step, the motivated the development of several computational input chemical structure is broken into fragments which tools in recent years [3, 15, 19]. Traditionally, these tools are complemented with functional groups necessary for implement methods based on precedent reaction look-up the reaction to take place. Te virtual reactants, referred or retrosynthetic analysis solutions [8]. Te former relies to as synthons in the remainder of this manuscript, can on the presence of a collection of reactions and attempts then be matched against a database of available building to match the query structure to a known reaction prod- blocks. -

Alkynes and Their Reactions Naming Alkynes • Alkynes Are Named in the Same General Way That Alkenes Are Named

Alkynes and Their Reactions Naming Alkynes • Alkynes are named in the same general way that alkenes are named. • In the IUPAC system, change the –ane ending of the parent alkane name to the suffix –yne. • Choose the longest continuous chain that contains both atoms of the triple bond and number the chain to give the triple bond the lower number. • Compounds with two triple bonds are named as diynes, those with three are named as triynes and so forth. • Compounds with both a double and triple bond are named as enynes. • The chain is numbered to give the first site of unsaturation (either C=C or C≡C) the lower number. Chapter 11 Preparation of Alkynes Preparation of Alkynes from Alkenes • Alkynes are prepared by elimination reactions. • Since vicinal dihalides are readily made from alkenes, one can convert an alkene • A strong base removes two equivalents of HX from a vicinal to the corresponding alkyne in a or geminal dihalide to yield an alkyne through two successive E2 two-step process involving: elimination reactions. • Halogenation of an alkene. • Double dehydrohalogenation of the resulting vicinal dihalide. • IMPORTANT NOTE: Synthesis of a terminal alkyne by dehydrohalogenation requires 3 equivalents of the base, due to the acidity of the terminal alkyne H H Br 3 equiv. NaNH2 HX Br H2O Terminal Alkynes – Reaction as an Acid Reactions of Alkynide Ions with Alkyl Halides • Terminal alkynes are readily converted to alkynide (acetylide) ions with strong • Acetylide anions are strong nucleophiles and react with unhindered alkyl halides to bases such as NaNH2 and NaH. yield products of nucleophilic substitution. -

Directed Evolution of Enzymes Using Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening

Research Collection Doctoral Thesis Directed Evolution of Enzymes using Ultrahigh-Throughput Screening Author(s): Debon, Aaron Publication Date: 2021 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-b-000502194 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library DISS. ETH NO. 27208 DIRECTED EVOLUTION OF ENZYMES USING ULTRAHIGH-THROUGHPUT SCREENING A thesis submitted to attain the degree of DOCTOR OF SCIENCES of ETH ZURICH (Dr. sc. ETH Zurich) presented by AARON DEBON MSc Interdisciplinary Sciences, ETH Zürich born on 15.11.1990 citizen of Einsiedeln, Schwyz accepted on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Donald Hilvert, examiner Prof. Dr. Andrew deMello, co-examiner 2021 Don’t play the butter notes. - Miles Davis Acknowledgements First, I would like to speak my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Don Hilvert for taking me in as his PhD student. His enthusiasm for science is a true inspiration and without his support and guidance none of this would have been possible. Additionally, I want to thank him for his excellent sportsmanship in the Schmutzli party. His ability ability not to laugh I will never forget. Along this line, I also want to thank Prof. Peter Kast, not only for being Don’s Schmutzli nemesis, but also for helpful inputs concerning everything microbiology. I’m grateful to Prof. Andrew deMello for refereeing this thesis and also the time I was able to spend working in his lab as a student. Furthermore, I want to thank Anita Meier-Lüssi and Antonella Toth for their help with administrative tasks and Leyla Hernandez for all her work in the lab. -

123.312 Advanced Organic Chemistry: Retrosynthesis Tutorial

123.312 Advanced Organic Chemistry: Retrosynthesis Tutorial Question 1. Propose a retrosynthetic analysis of the following two compounds. Your answer should include both the synthons, showing your thinking, and the reagents that would be employed in the actual synthesis. Compound A O Answer: FGI OH C–C OH O dehydration O aldol O ! ! O O Remember that a conjugated double bond can easily be prepared by dehydration, thus we can perform an FGI to give the aldol product. The 1,3-diO relationship should make spotting the disconnection very easy. Of course, in the forward direction the reaction is not quite that simple; we have two carbonyl groups so we must selectively form the correct enolate but this should be possible by low temperature lithium enolate formation prior to the addition of cyclohexanone. The aldol condensation is such a common reaction that it is perfectly acceptable to do the following disconnection: O O ! ! O O Compound B O O Answer O O O O ! FGI O O HO 1 2 OH HO O 3 5 reduction 4 C–C O O HO ! ! O O O EtO OEt The first disconnection should be relatively simple, break the C–O bond to give the acid and alcohol. The next stage might be slightly tougher…your best bet is to look at the relationship between the two functional groups; it is 1,5. This can be formed via a conjugate addition of an enolate. To do this we need two carbonyl groups so next move is a FGI to form the dicarbonyl. Two possible disconnections are now possible depending on which enolate we add to which activated alkene. -

Common Synthetic Sequences for Ochem I

COMMON SYNTHETIC SEQUENCES FOR OCHEM I Students frequently get overwhelmed by the increasingly large number of organic reactions and mechanisms they must learn. This task is made particularly difficult by the perception that it is just “busy work,” and that it serves no purpose other than to meet an academic requirement. It is true that a lot of organic reactions seem to lack meaning in and of themselves, but obviously they are not useless. Unfortunately students do not get exposed to the contexts in which this information comes to life until later, or sometimes never. The context of most immediate relevance from the point of view of the organic chemistry student is in the application of these reactions in synthesis. A synthesis is a series of two or more reactions designed to obtain a specific final product. A synthetic step (not to be confused with a mechanistic step, which is something entirely different) is a single reaction that must be conducted separately from the others in a synthesis. Therefore the number of steps in a synthetic sequence is the same as the number of reactions that must be conducted separately, that is to say, the number of reactions that make up the sequence. The concept of synthetic strategy refers to the design of the most efficient combination of reactions that will yield the desired final product. This concept is widely used in R&D departments in the pharmaceutical industry to obtain synthetic drugs of many kinds. This type of research brings together widely different fields of science such as biochemistry, organic chemistry, biology, and even computer science into a single integrated task: the task of drug discovery.