The Quality of Patient Engagement and Involvement in Primary Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

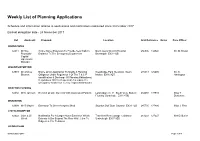

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Weekly List of Planning Applications Schedule and information relating to applications and notifications registered since 30 October 2017 Earliest delegation date - 24 November 2017 Ref Applicant: Proposal: Location Grid Reference Notes Case Officer BARNSTAPLE 64011 Mr Rae Single Storey Extension To Provide New Walk In North Devon District Hospital 256506 134540 Mr. M. Brown Reynolds - Entrance To The Emergency Department Barnstaple EX31 4JB Capital Operations Manager BISHOPS NYMPTON 63973 Mr Andrew Notice Of An Application To Modify A Planning Westbridge Park Newtown South 275843 125605 Mr. S. Blowers Obligation Under Regulation 3 Of The T & C P Molton EX36 3QT Harrington (modification & Discharge Of Planning Obligations) Regulations 1992 In Respect Of Amending The Occupancy Restriction To Key / Agricultural Worker BRATTON FLEMING 64032 Mr K Jackson Erection Of One Dwelling With Associated Parking Land Adjacent 11 South View Bratton 264658 137910 Miss T Fleming Barnstaple EX31 4TQ Blackmore BRAUNTON 63994 Mr R Mayne Extension To Green-keepers Shed Saunton Golf Club Saunton EX33 1LG 245735 137486 Miss J. Pine CHITTLEHAMPTON 64022 John & Jill Notification For A Larger Home Extension Which Travellers Rest Cottage Cobbaton 261233 127227 Mrs D. Butler O'neil Extends 4.00m Beyond The Rear Wall, 3.6m To Umberleigh EX37 9SD Ridge & 2.31m To Eaves GEORGEHAM 06 November 2017 Page 1 of 4 64025 Mr M Notification Of Works To Trees In A Conservation St Georges House Georgeham 246504 139931 42 Days Mr. A. Jones Larrington Area In Respect Of Re-pollarding Of Sycamore Braunton EX33 1JN Notice LB (group A) And Lime (group B), Crown Reduction Of CA Cherry (b), Selective Branch Removal From Sycamore (e) & Recoppicing Of Sycamore (d&e) 64008 Mr & Mrs Erection Of Replacement Dwelling Together With 1 Stoney Cottage Croyde Braunton 243851 139458 Miss S. -

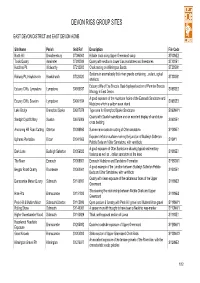

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

North Devon AONB RIGS

REPORT ON THE ASSESSMENT OF COUNTY GEOLOGICAL SITES IN THE NORTH DEVON AREAS OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Phase 2 Area from Saunton - Morte Point – Ifracombe and Ilfracombe – Combe Martin REPORT ON THE ASSESSMENT OF COUNTY GEOLOGICAL SITES IN THE NORTH DEVON AREAS OF OUTSTANDING NATURAL BEAUTY Phase 2 Area from Saunton - Morte Point – Ifracombe and Ilfracombe – Combe Martin E.C. FRESHNEY and J.A. BENNETT Prepared by: Devon RIGS Group February, 2006 For: Northern Devon Coast and Countryside Service CONTENTS Introduction 1 Summary of the geology of the North Devon AONB and its immediate surroundings 6 Appendix 1 Description of sites Appendix 2 Glossary FIGURES Figure 1 Map showing area of northern part of North Devon AONB with positions of SSSIs, GCRs and proposed County Geological Sites 3 Figure 2 Geological map of the northern part of the North Devon AONB 7 Figure 3 Stratigraphy of the northern part of the North Devon AONB 8 Figure 4 Generalised relationship of cleavage to bedding in the North Devon area showing possible thrust fault at depth. 12 TABLES Table 1 Geological SSSIs and GCRs in North Devon AONB 3-4 Table 2. Proposed County Geological Sites 5 PLATES (All in Appendix 1) Plate 1 Purple sandstones and greenish grey slates and siltstones of Pickwell Down Sandstones. Plate 2 Purple sandstone in Pickwell Down Sandstones showing more massive lower part to right overlain by more muddy laminated upper part where the cleavage is more marked ..Plate 3. Top part of sandstone seen in Figure 2 showing cross-bedding and cleavage. Plate 4 Sandstone showing small scale cross-lamination (ripple drift bedding) Plate 5 Purple sandstones with greenish grey siltstones and a mud clast conglomerate. -

Adventures at Longlands Adventures on Exmoor & North Devon

Adventures at Longlands Longlands has a boating lake and 2 skiffs: Oxford & Cambridge, so you can race around the island in your very own Boat Race! Each boat can take one adult and one child. Life jackets of varying sizes are provided. There are stream walks and nature trails in our woods, and lots of sticks with which to practice den building. We have a number of outdoor games including petanque/boules, cricket, rounders and badmington, all of which can be played in the lakeside meadow. There is a football goal on the football field, a cricket net above it and a basketball & netball hoop near the Larder. So score a goal, hit a run or shoot a hoop! Our streamside and woodland walks are very sheltered, so are excellent for rainy days. Bug hunt along the stream, discover animal tracks and perhaps even spot deer in the woods. Our shop is stocked with lots of adventure kits including Bug Hunting, Ponding dipping, Bird spotting and even Den kits and kites! Within the lodges themselves we have a box of favourite family games including Monopoly, Scrabble, Cluedo, Risk, Jengo, Dominoes, Uno & playing cards, and in the Larder you’ll find plenty of books to borrow. Next to the Longlands Larder there is a covered area with Table Tennis & Giant Jenga and within the shop itself there are colouring and activity books to provide endless entertainment even on the wettest of days. Exmoor is the best place for stargazing in the UK, according to the Campaign for Dark Skies. In fact it is the first designated International Dark Sky Reserve in Europe - and Longlands looks directly on to it - Definitely worth staying up for on a clear night. -

Understanding Exmoors Economy

31/10/2019 Understanding the Exmoor Economy Oliver Allies & Declan Turner [email protected] 24th October Project • Identify businesses on Exmoor o Collected data from Companies House and Experian o Supplemented with details obtained via online web scraping • Survey businesses on Exmoor o Light touch survey to be distributed online o Comprehensive follow-up telephone survey • Analyse results o How big are these businesses? o Why are they here? o Where do their staff live? o What challenges do they face? o What are the opportunities for businesses on Exmoor? 1 31/10/2019 Which businesses? • Previous results from national data show there are approximately 800 businesses on Exmoor • Our business identification work has found 1,050 operating businesses • 285 have identified sectors • Many are in agriculture (39%) and tourism (14%) • Other sectors also have a strong representation: o 14 % of firms are Professional Scientific & Technical Activities o 8% of firms are in Construction o 8% of firms are in IT • Part of our survey work will be to identify sectors for the remaining businesses Where are the businesses? Clusters around Lynton, Porlock, Minehead and Dulverton 2 31/10/2019 Survey http://bit.ly/ExmoorRESurvey • Need support from everyone here to push the survey across their networks through social media, email, word of mouth • Important information for the Rural Enterprise Exmoor and the partners o Without data to drive decisions appropriate support cannot be designed o Help shape future plans and direction for the National Park, -

RIVERSIDE PARK & COUNTRY CLUB South Molton We Currently Have the Following Vacancies: NEW CHEFS & NEW MENUS Restaurant Supervisors

RIVERSIDE PARK & COUNTRY CLUB South Molton We currently have the following vacancies: NEW CHEFS & NEW MENUS Restaurant Supervisors PARTY SEASON Waiting Staff (full and part time) Chefs NOW TAKING BOOKINGS IN THE Now Open (from commis to junior sous-chefs) RESTAURANT FOR DECEMBER Vacancies have arisen due to the All Day On FAMILY, FRIENDS & WORK COLLEAGUES TO ENJOY THE forthcoming opening of the Saturdays! CHRISTMAS CELEBRATIONS Laura Ashley Tea Room and the success of our restaurant business Your Local Independent FABULOUS ACTS BOOKED Veterinary Centre. [NOT TO BE MISSED] Tel: 01769 540 561 and ask for the GREAT NEW MENU HR Department Southley Road Send your CV and covering letter to South Molton NEW LUXURIOUS EN SUITE ROOMS NOW AVAILABLE FOR BOOKINGS [email protected] Tel: 01769 572176 Email [email protected] Highbullen Hotel Golf and Country Club, Phone 01769 579269 Chittlehamholt Wren Music presents a Winter Concert with CANCER RESEARCH UK seasonal music and songs from North Devon Christmas Coffee Morning: Thursday community music groups: 6th December from 10am-12 noon in the * The Folk Orchestra of North Devon * North Dev- Assembly Rooms, South Molton. Coffee and on Folk Choir * Roots Acoustic * North Devon homemade cakes, gift stalls, raffle, cake stall. Roots Band * North Devon Family Roots Quiz Night: Friday 14th December at 7 for Refreshments and Raffle. On Saturday 8th De- 7.30pm, at The Sportsmans Inn, Sandyway. cember at 7.30pm at Filleigh Village Hall. Tickets £12.50 including roast turkey with all the Entry by donation (proceeds to Wren's youth trimmings, available from Committee members or roots music programme) Contact becki@wren Quince Honey Farm 01769 572401. -

Chapter 4 Culm Basin E.C. FRESHNEY, B.E. LEVERIDGE, R.A. WATERS & C.N

Culm Basin 27/02/2012 Chapter 4 Culm Basin E.C. FRESHNEY, B.E. LEVERIDGE, R.A. WATERS & C.N. WATERS To the south of the Mississippian platform carbonate successions of South Wales (Chapter 5) and Bristol, Mendips and Somerset (Chapter 6), Carboniferous rocks predominantly occur within the strongly deformed Culm synclinorial belt of South- west England. The Culm Basin has a broad graben architecture, with an inner graben (Central Devon Sub-basin) flanked by half-grabens (Bideford and Launceston sub- basins) (Fig. 4.1; Leveridge & Hartley 2006; Waters et al. 2009). The Bideford Sub- basin is bounded to the north by the Brushford Fault, the Central Devon Sub-basin by the Greencliff Fault and the Launceston Sub-basin by the Rusey Fault. To the north of the Brushford Fault is the Northern Margin of the Culm Basin. The Tavy Basin has limited development of Famennian to Tournaisian strata. The High separating the Tavy Basin and Launceston Sub-basin includes a Tournaisian to ?Visean succession (Yeolmbridge and Laneast Quartzite formations). Remnants of Carboniferous strata also occur in the South Devon Basin. In many areas there is no clear lithological break between the Tournaisian and the underlying Upper Devonian rocks, both of which are dominated by shallow marine and deeper water mudstones. The succession, commonly referred to as the Transition Series or Group (Dearman & Butcher 1959; Freshney et al. 1972), are assigned to the Exmoor Group in north Devon, the Hyner Mudstone and Trusham Mudstone formations of the eastern part of the Central Devon Sub-basin and the Tamar Group in south Devon. -

Some Economic Aspects of the Beef Cattle Industry in the West of England

L. 4'215 .s UNIVERSITY OF PISTOL ,.•., DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS (Agricultural Economics) Selected Papers in Agricultural Economics Vol. IV. No. 3. Some Economic Aspects of the Beef Cattle Industry in the West of England Report No. 2 Cattle Rearing and Milk Production in the Upland Area of S.W. Somerset 1 9 s 2 - 53 by R. R. JEFFERY Price 51- „ Some Economic Aspects of the Beef Cattle Industry in the West of England Report No. 2 Beef Store Cattle Rearing and Milk Production in the Upland Area of S.W. Somerset I 9 5 2 - 5 3 by R. R. JEFFERY November '954 Acknowledgement This opportunity is gratefully accepted to acknowledge the extreme helpfulness and unfailing courtesy of those Brendon Hills and Exmoor farmers who co-operated with this Depart- ment in making available so readily the large amount of detailed information involved in this investigation. A special debt of gratitude is due to a number of farmers for whom this present investigation represents the third consecutive year of participation in survey work of an exacting and protracted nature. 255 Introduction THIS investigation forms the second in a series designed to cover, ultimately, the main systems of beef cattle production in the West of England. The previous survey* carried out in 1950-51 showed the rearing of beef stores, as practised in the upland marginal farming areas of N.W. Hereford, to be an unprofitable enterprise. Since that time however store cattle prices have advanced considerably, while a special Production Grant payable at the rate of flO per head on eligible cows on upland rearing farms has been introduced, developments which together must have raised considerably the returns from store cattle rearing in these areas. -

Stogursey News January 2021

STOGURSEY NEWS ! PW January 2021 Editorial Deadline for February contributions: 10.00 am Friday 15th January 2021 Welcome to the January issue of Stogursey News. In this issue we both look back and forward. Firstly, looking back, there are some happy accounts and How to contribute to Stogursey News: great photos of our school’s Christmas activities, a) by email: which the pupils all seemed to have thoroughly en- Prepare your contribution as a ‘word’ document. joyed - even making the best of this year’s restrictions Attach it to an email. Send it to [email protected] by filming their Christmas Nativity. b) by hand: Looking ahead, you’ll see that the Film Club is keen Write or type your contribution. to get going again later in the year, for a summer sea- Put it into the ‘Stogursey News’ box in the Post son. What a great idea to have an Opening Night. Office. Also, the Community Bus Service is very much up and running again – the timetable is printed inside. A few points to remember: • Submit your contribution by the deadline date. • Keep within the 500-word limit. January is traditionally when we make New Year’s resolutions. Take time to read the pages explaining • Provide your contact details so that we can get in touch if we need to edit. how we, in this parish, can apply for £75,000 worth (Stogursey News Team reserves the right to edit of funding to help tackle the growing climate emer- contributions for length and layout.) gency. There are lots of ideas to think about. -

Rural Enterprise Exmoor Research Report

Rural Enterprise Exmoor The Rural Enterprise Exmoor initiative has been set up by Exmoor National Park Authority, in conjunction with relevant partners. It aims to build a better understanding of the rural economy of Exmoor, in order to support sustainable economic development in harmony with Exmoor’s designation as a National Park. Tel: 01398 323665 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @RuralEntExmoor Facebook: www.facebook.com/RuralEntExmoor More information: www.exmoor-nationalpark.gov.uk/living-and-working/business-and-economy/rural-enterprise- exmoor Wavehill: social and economic research Report authors: Declan Turner Oliver Allies Eddie Knight Sarah Usher Tel: 01545 571711 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @wavehilltweets More information: www.wavehill.com Rural Enterprise Exmoor Research Report Acknowledgements The Rural Enterprise Exmoor Steering Group and Exmoor National Park Authority would like to thank all those who contributed to this work. This report has been compiled by Wavehill – an independent economic and social research company. Special thanks are extended to the many individuals from the Exmoor business community who gave their time to assist in this research, especially those that participated in the survey, workshops and focus groups. The research was funded with contributions from Exmoor National Park Authority, the West Somerset Opportunity Area, the Heart of the South West Local Enterprise Partnership, Somerset West and Taunton Council and North Devon Council. Rural Enterprise Exmoor Steering Group Dan James (Sustainable Economy Manager, Exmoor National Park Authority) Dean Kinsella (Head of Planning and Sustainable Development, Exmoor National Park Authority) Ruth McArthur (Policy and Community Manager, Exmoor National Park Authority) Dominie Dunbrook (Senior Economic Development Officer, North Devon Council) Dr. -

Blue Sky Meeting Held on Monday, 13 July 2015 at 6Pm

Minutes of Georgeham Church of England Primary School Full Governing Body Blue Sky Meeting held on Monday, 13 July 2015 at 6pm. Chaired by: Ali Smith Clerked by: Sue Squire Present: Agenda: - Prayer Neill Hakin NH Apologies David Humphries DH Declarations of Interest David Morton DM Blue Sky Discussion Ali Smith AS Chairman’s Business Julian Swanne JS Date of next Meeting Julian Thomas (Head Teacher) JT Jane Young JY Action: 1. Prayer. David Morton opened the Meeting with prayer. 2. Apologies. Mike Newbon (PCC Meeting), Judith Larrington, Lucy Rinvolucri. 3. Declarations of Interest. None. 4. Blue Sky Discussion: Governors were circulated with paperwork to support discussion in the meeting: 1. Analysis of School Status in Devon – source: School Census Data 2014/15 Primary Schools Only. 2. Which schools are available in Devon – source Babcock LDP. 3. Self-Evaluation of Georgeham Primary School based upon the format used in an OFDTED inspection summary (template from a recently inspected ‘good’ school). Prepared by Julian Thomas, Alison Smith – July 2015. 4. Summary of results 2014/15 – provided by JT AS opened the meeting with a summary of the purpose of the Blue Sky: an opportunity for governors to meet, review progress of the school and consider plans for the future mindful of two key questions: 1. Where do we see our school today and in 3 – 5 years time? 2. What do we need to focus on to deliver the best outcomes for the children within it today and in the future? 4.1 Status of the School – what could / should it look like in 3 – 5 years time. -

Ar-Enpa-04.09.18-Item 11.Pdf

ITEM 11 EXMOOR NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY 4 September 2018 MOOR TO ENJOY (A HEALTH AND WELLBEING PARTNERSHIP) PROJECT COMPLETION AND FINAL REPORT Report of the Head of Information and Communication Purpose of the report: To report on the completion of the Moor to Enjoy Project (a health and wellbeing partnership). RECOMMENDATION(S): The Authority is recommended to: (1) RECEIVE the Moor to Enjoy Final Report (2) NOTE the Project successes and learning (3) THANK Devon and Somerset Health and Wellbeing Boards for commissioning the Project. Authority Priority: Support delivery of the Exmoor National Park Partnership Plan ambition for People: Exmoor for All: where everyone feels welcome. Legal and Equality Implications: Section 65(4) Environment Act 1995 – provides powers to the National Park Authority to “do anything which in the opinion of the Authority, is calculated to facilitate, or is conducive or incidental to- (a) the accomplishment of the purposes mentioned in s. 65 (1) [National Park purposes] (b) the carrying out of any functions conferred on it by virtue of any other enactment.” The equality impact of the recommendation(s) of this report has been assessed as follows: There are no negative equality implications arising from the recommendations of this report. Consideration has been given to the provisions of the Human Rights Act 1998 and an assessment of the implications of the recommendation(s) of this report is as follows: There are no negative implications arising from the recommendations of this report. Financial and Risk Implications: There are no financial implications arising from the recommendations of this report. 1 1.