Devon Building Stone Atlas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes Template

PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY COMMITTEE 6/07/17 PUBLIC RIGHTS OF WAY COMMITTEE 6 July 2017 Present:- Councillors P Sanders (Chairman), T Inch, J Brook, I Chubb, P Colthorpe, A Dewhirst, R Edgell, M Shaw and C Whitton * 33 Minutes RESOLVED that the minutes of the meeting held on 2 March 2017 be signed as a correct record. * 34 Items Requiring Urgent Attention There was no matter raised as a matter of urgency. * 35 Announcements The Chairman announced that a visit to the Devon Heritage Centre would be arranged for the Autumn, before the November meeting, by way of further training for new Members and the Acting Chief Officer for Highways, Infrastructure and Development would notify Members of the proposed date in due course. * 36 Devon Countryside Access Forum The Committee received and noted the draft minutes of the meeting held on 27 April 2017. * 37 Parish Review: Definitive Map Review 1997-2017 - Parish of Burlescombe The Committee received the Report of the Acting Chief Officer of Highways, Infrastructure and Waste (HIW/17/48) on the outcome of the Definitive Map Review in the Parish of Burlescombe in Mid Devon District. It was MOVED by Councillor Sanders, SECONDED by Councillor Brooks and RESOLVED that it be noted that the Definitive Map Review had been completed in the Parish of Burlescombe and no modifications were required to be made. * 38 Parish Review: Definitive Map Review - Parish of Bittadon, with Marwood and West Down The Committee considered the Report of the Acting Chief Officer for Highways, Infrastructure Development and Waste (HIW/17/49) examining a claim submitted by the Trail Riders Fellowship in November 2005 in the Parish of Bittadon. -

Westwood, Land Adjoining Junction 27 on M5, Mid Devon

WESTWOOD, LAND ADJOINING JUNCTION 27 ON M5, MID DEVON ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK BASED ASSESSMENT Prepared for GL HEARN Mills Whipp Projects Ltd., 40, Bowling Green Lane, London EC1R 0NE 020 7415 7044 [email protected] October 2014 WESTWOOD, LAND ADJOINING JUNCTION 27 ON M5 ARCHAEOLOGICAL DESK BASED ASSESSMENT Contents 1. Introduction & site description 2. Report Specification 3. Planning Background 4. Archaeological & Historical Background 5. List of Heritage Assets 6. Landscape Character Assessment 7. Archaeological Assessment 8. Impact Assessment 9. Conclusions Appendix 1 Archaeological Gazetteer Appendix 2 Sources Consulted Figures Fig.1 Site Location Fig.2 Archaeological Background Fig.3 Saxton 1575 Fig.4 Donn 1765 Fig.5 Cary 1794 Fig.6 Ordnance Survey 1802 Fig.7 Ordnance Survey 1809 Fig.8 Ordnance Survey 1830 (Unions) Fig.9 Ordnance Survey 1850 (Parishes) Fig.10 Ordnance Survey 1890 Fig.11 Ordnance Survey 1906 Fig.12 Ordnance Survey 1945 (Landuse) Fig.13 Ordnance Survey 1962 Fig.14 Ordnance Survey 1970 Fig.15 Ordnance Survey 1993 Fig.16 Site Survey Plan 1. INTRODUCTION & SITE DESCRIPTION 1.1 Mills Whipp Projects has been commissioned by GL Hearn to prepare a Desk Based Assessment of archaeology for the Westwood site on the eastern side of Junction 27 of the M5 (Figs.1, 2 & 17). 1.2 The site is centred on National Grid Reference ST 0510 1382 and is approximately 90 ha (222 acres) in area. It lies immediately to the east of the Sampford Peverell Junction 27 of the M5. Its northern side lies adjacent to Higher Houndaller Farmhouse while the southern end is defined by Andrew’s Plantation, the lane leading to Mountstephen Farm and Mountstephen Cottages (Fig.16). -

Parish Profile for a Prospective Training Post

HOLY TRINITY & ST PETER, ILFRACOMBE WITH ST PETER, BITTADON PARISH PROFILE FOR A PROSPECTIVE TRAINING POST General Information The Parishes of Ilfracombe (Holy Trinity and St Peter’s) and Bittadon, within the Ilfracombe Team Ministry in the Shirwell Deanery The Benefice includes five parishes and six churches. The Team Rector assumes responsibility for Holy Trinity and St Peter’s in Ilfracombe and St Peter’s Bittadon. The Rev’d Keith Wyer has PTO. The Team Vicar, the Rev’d Preb. Giles King-Smith, assumes responsibility for the Parishes of Lee, Woolacombe and Mortehoe. He is presently assisted by the self-supporting priest, the Rev’d Ann Lewis. The Coast and Combe Mission Community includes the Coast to Combe benefice (SS Philip and James, Ilfracombe, St Peter, Berrynarbor, St Peter ad Vincula, Combe Martin) under their Vicar, the Rev’d Peter Churcher. Training Incumbent The Rev’d John Roles – usually known as Father John or simply, John, and his wife Sheila. The Vicarage, St Brannock’s Road, Ilfracombe EX34 8EG – 01271 863350 – [email protected] Date of ordination: Deaconed 2012, Priested 2013 Length of time in present parish: 23 years as a layman, 4 years as self-supporting curate, 4 years as incumbent Other responsibilities and duties currently undertaken by incumbent: Foundation Governor at Ilfracombe CofE Junior School. Chaplaincy Team member at Ilfracombe Academy Chair of ICE Ilfracombe Vocations Advisor Independent Director of One Ilfracombe Chaplain to Royal British Legion Ist Ilfracombe (Holy Trinity) Scouts ex-officio Committee member Member of Compass Rotary Club Previous posts and experience of incumbent, including details of experience with previous curates: I have been in Ilfracombe for a long time! For twenty years I was teaching English at the Park School in Barnstaple (following 12 years of teaching in London). -

May 2021.Cdr

Parish Magazine Ashprington Cornworthy Dittisham May 2021 Away with the Fairies in 1917. My three year old granddaughter Lily loves fairy stories and so, apparently, did Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes. He totally believed in the Cottingley Fairies. In 1917 two talented cousins, Elsie Wright (16) and Frances Griffiths (9), borrowed their father's camera and went down through the bottom of the garden to Cottingley Beck, a stream near Bradford in Yorkshire. There Elsie took five photographs, beautifully composed, showing her cousin Frances watching with a rapt expression a group of fairy folk dancing in front of her. Other photographs showed fairies flying around and a gnome on the grass. The whole process took about half an hour. Such was the skill of the girls' composition that Elsie's mother believed that the little figures really were fairies. Her father, who developed the images, did not believe they were real and considered that the girls had used cardboard cut outs of fairies in the photographs. He refused to lend them his camera again. Elsie's mother Polly was a Theosophist. She went to a meeting in Bradford which happened to be about fairies. She told the president of the Harrogate Theosophists, Edward Gardner, about the photographs and he examined them. Having pronounced them genuine he later contacted Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, a well known Spiritualist, who was writing a piece on fairies for the 1920 Christmas edition of the Strand Magazine. Doyle was totally convinced that the images were real and asked permission to use them in his article. -

Ringing Devon

Ringing THE GUILD OF DEVONSHIRE RINGERS Devon Newsletter 108, December 2017 MERRY CHRISTMAS David took the trouble to go into detail about the principles Guild Events behind the judging, how judges like he and his wife Felicity approached the subject, what they looked for. He also gave Striking Competitions – Saturday October 21st detailed advice on how to proceed at the event, how to make the The Guild striking competitions 2017- a novice’s view most of the time and tips and hints for leading and tenor ringing. Held at three separate towers and organised by the North East With his kind permission, we have put together a transcript of his Branch, this year’s Guild competitions were a wholehearted remarks which is published as a separate article in this issue. success. Seen from the writer’s perspective - that of an entirely But the ringing is only part of a successful competition day. The novice ringer - the day showed all those qualities which ringers venues of Bampton and Stoodleigh in the morning and Silverton tend to take entirely for granted - qualities of true comradeship. in the afternoon provided what we all are tempted to take for Ringers are the most friendly group of people you’ll find and they granted in this Guild, that someone always provides tea, coffee came together on the 21st October with one purpose in mind - and biscuits for a mere pittance of a contribution. But at Silverton that of bringing the traditional music of the church tower to new the whole distaff side seemed to have been galvanized - no bread heights. -

4 Brooking Barn Ashprington, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7UL

57 Fore Street, Totnes, Devon TQ9 5NL. Tel: 01803 863888 Email: [email protected] REF: DRO1267 4 Brooking Barn Ashprington, Totnes, Devon TQ9 7UL A MOST ATTRACTIVE DOUBLE FRONTED VILLAGE RESIDENCE, FORMERLY AN OPEN STONE PILLARED BARN CONVERTED TO PROVIDE A SPACIOUS ACCOMMODATION BRIEFLY COMPRISING:- ENTRANCE HALL, LOUNGE, KITCHEN/DINING ROOM, THREE BEDROOMS, EN-SUITE & FAMILY BATHROOM. WITH GARAGE & GARDEN. * * * Offers in the Region of £265,000 * * * www.rendells.co.uk 4 Brooking Barn, Ashprington SITUATION Situated within the very popular and picturesque village of Ashprington, the property stands with a sizable front garden and garage within a party block. Ashprington is approximately two and a half miles from Totnes and within easy driving of the nearby towns of Dartmouth and Kingsbridge. Totnes has a mainline railway station bringing London with three hours travelling, and a choice of two supermarkets with a compliment of multiple and independent shops. The coastlines of the South Hams are within an easy drive as is Dartmoor National Park. DIRECTIONS From Totnes, drive along Station Road in the direction of the station. Proceeding past the station, turn left at the traffic lights on to the Kingsbridge and Dartmouth road. Proceed up the hill through the next set of traffic lights (ignoring the next two turnings on the left) and just beyond the small lodge house on the left there is a turning on the left signposted ‘Ashprington’. Take this turning and drive until you enter the village. Proceeding down the hill into the village, bear right of the monument in front of you. A little way down this lane on the left hand side is No.4 Brooking Barn. -

PDF of Hayne Local Hotels, B&Bs & Inns Oct 2019

Accommodation Nearby Local B&Bs, Hotels & Inns The Waie Inn, Zeal Monachorum EX17 6DF t: 01363 82348 www.waieinn.co.uk (0.5 miles) (1/2 mile walking distance from Hayne Devon) Self Catering Cottages available (3 nights min) 16 B&B Rooms from £40 per person, per night * AMAZING INDOOR SOFT PLAY & OUTDOOR PLAYGROUND FOR KIDS, * PUB (doing simple food), SKITTLES, SQUASH, SNOOKER & SWIMMING POOL The Old Post Office, Down St Mary EX17 6DU (2.2 miles) t: 01244 356695 https://www.northtawton.org/self-catering-accommodation/ Larksworthy House, North Tawton EX20 2DS (3 miles) t: 01244 356695 https://www.northtawton.org/self-catering-accommodation/ Homefield, Lapford EX17 6AF (3.5 miles) t: 01363 83245 Joy & David Quickenden e: [email protected] 2 luxury double B&B rooms, £90 per room or £160 for a 2 night stay (Additional beds at £10 per child can be added to each room) Lowerfield House, Lapford EX17 6PU (3.6 miles) t: 01363 507030 Steve & Sandra Munday https://lowerfieldhouse.co.uk/ The Cottage, Lapford Mill, Lapford EX17 6PU (3.6 miles) t: 07815 795918 [email protected] http://www.lapfordmill.uk/the-cottage Burton Hall, North Tawton EX20 2DQ (4 miles) t: 01837 880023 / 0770 801 8698 www.burton-hall.co.uk The Cabin at Burton Hall, £55 (2 guests) East Wing at Burton Hall £90 (Sleeps 4) Self Contained Annexe £50 (2 guests) Alistair Sawday recommends … The Linhay, Copplestone EX17 5NZ (4 miles) t: 01363 84386 www.smilingsheep.co.uk £95 per night, £150 for a 2 night stay Harebell B&B, Copplestone EX17 5LA (4 miles) t: 01363 84771 www.harebellbandb.co.uk -

Environment Agency South West Region

ENVIRONMENT AGENCY SOUTH WEST REGION 1997 ANNUAL HYDROMETRIC REPORT Environment Agency Manley House, Kestrel Way Sowton Industrial Estate Exeter EX2 7LQ Tel 01392 444000 Fax 01392 444238 GTN 7-24-X 1000 Foreword The 1997 Hydrometric Report is the third document of its kind to be produced since the formation of the Environment Agency (South West Region) from the National Rivers Authority, Her Majesty Inspectorate of Pollution and Waste Regulation Authorities. The document is the fourth in a series of reports produced on an annua! basis when all available data for the year has been archived. The principal purpose of the report is to increase the awareness of the hydrometry within the South West Region through listing the current and historic hydrometric networks, key hydrometric staff contacts, what data is available and the reporting options available to users. If you have any comments regarding the content or format of this report then please direct these to the Regional Hydrometric Section at Exeter. A questionnaire is attached to collate your views on the annual hydrometric report. Your time in filling in the questionnaire is appreciated. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY Contents Page number 1.1 Introduction.............................. .................................................... ........-................1 1.2 Hydrometric staff contacts.................................................................................. 2 1.3 South West Region hydrometric network overview......................................3 2.1 Hydrological summary: overview -

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Weekly List of Planning Applications Schedule and information relating to applications and notifications registered since 30 October 2017 Earliest delegation date - 24 November 2017 Ref Applicant: Proposal: Location Grid Reference Notes Case Officer BARNSTAPLE 64011 Mr Rae Single Storey Extension To Provide New Walk In North Devon District Hospital 256506 134540 Mr. M. Brown Reynolds - Entrance To The Emergency Department Barnstaple EX31 4JB Capital Operations Manager BISHOPS NYMPTON 63973 Mr Andrew Notice Of An Application To Modify A Planning Westbridge Park Newtown South 275843 125605 Mr. S. Blowers Obligation Under Regulation 3 Of The T & C P Molton EX36 3QT Harrington (modification & Discharge Of Planning Obligations) Regulations 1992 In Respect Of Amending The Occupancy Restriction To Key / Agricultural Worker BRATTON FLEMING 64032 Mr K Jackson Erection Of One Dwelling With Associated Parking Land Adjacent 11 South View Bratton 264658 137910 Miss T Fleming Barnstaple EX31 4TQ Blackmore BRAUNTON 63994 Mr R Mayne Extension To Green-keepers Shed Saunton Golf Club Saunton EX33 1LG 245735 137486 Miss J. Pine CHITTLEHAMPTON 64022 John & Jill Notification For A Larger Home Extension Which Travellers Rest Cottage Cobbaton 261233 127227 Mrs D. Butler O'neil Extends 4.00m Beyond The Rear Wall, 3.6m To Umberleigh EX37 9SD Ridge & 2.31m To Eaves GEORGEHAM 06 November 2017 Page 1 of 4 64025 Mr M Notification Of Works To Trees In A Conservation St Georges House Georgeham 246504 139931 42 Days Mr. A. Jones Larrington Area In Respect Of Re-pollarding Of Sycamore Braunton EX33 1JN Notice LB (group A) And Lime (group B), Crown Reduction Of CA Cherry (b), Selective Branch Removal From Sycamore (e) & Recoppicing Of Sycamore (d&e) 64008 Mr & Mrs Erection Of Replacement Dwelling Together With 1 Stoney Cottage Croyde Braunton 243851 139458 Miss S. -

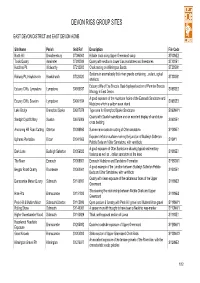

Devon Rigs Group Sites Table

DEVON RIGS GROUP SITES EAST DEVON DISTRICT and EAST DEVON AONB Site Name Parish Grid Ref Description File Code North Hill Broadhembury ST096063 Hillside track along Upper Greensand scarp ST00NE2 Tolcis Quarry Axminster ST280009 Quarry with section in Lower Lias mudstones and limestones ST20SE1 Hutchins Pit Widworthy ST212003 Chalk resting on Wilmington Sands ST20SW1 Sections in anomalously thick river gravels containing eolian ogical Railway Pit, Hawkchurch Hawkchurch ST326020 ST30SW1 artefacts Estuary cliffs of Exe Breccia. Best displayed section of Permian Breccia Estuary Cliffs, Lympstone Lympstone SX988837 SX98SE2 lithology in East Devon. A good exposure of the mudstone facies of the Exmouth Sandstone and Estuary Cliffs, Sowden Lympstone SX991834 SX98SE3 Mudstone which is seldom seen inland Lake Bridge Brampford Speke SX927978 Type area for Brampford Speke Sandstone SX99NW1 Quarry with Dawlish sandstone and an excellent display of sand dune Sandpit Clyst St.Mary Sowton SX975909 SX99SE1 cross bedding Anchoring Hill Road Cutting Otterton SY088860 Sunken-lane roadside cutting of Otter sandstone. SY08NE1 Exposed deflation surface marking the junction of Budleigh Salterton Uphams Plantation Bicton SY041866 SY0W1 Pebble Beds and Otter Sandstone, with ventifacts A good exposure of Otter Sandstone showing typical sedimentary Dark Lane Budleigh Salterton SY056823 SY08SE1 features as well as eolian sandstone at the base The Maer Exmouth SY008801 Exmouth Mudstone and Sandstone Formation SY08SW1 A good example of the junction between Budleigh -

W.J. B , B.E. L and C.N. Waters

DRAFT – FOR BGS APPROVAL THE GLOBAL DEVONIAN, CARBONIFEROUS AND PERMIAN CORRELATION PROJECT: A REVIEW OF THE CONTRIBUTION FROM GREAT BRITAIN 1 2 2 3 G. WARRINGTON , W.J. BARCLAY , B.E. LEVERIDGE AND C.N. WATERS Warrington, G., Barclay, W.J., Leveridge, B.E. and Waters, C.N. 201x. The Global Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian Correlation Project: a review of the contribution from Great Britain. Geoscience in South-West England, 13, xx-xx. A contribution on the lithostratigraphy and palaeoenvironments of Devonian, Carboniferous and Permian successions onshore in Great Britain, prepared for an international project, is summarised with particular reference to south-west England. Devonian and Carboniferous successions present in that region occur in the Rhenohercynian Tectonic Zone, to the south of the Variscan Front (VF), and their complexity reflects formation in six composite basins. They differ substantially from contemporaneous successions north of the VF. Whereas Devonian successions south of the VF are largely marine, those to the north are continental. Carboniferous successions south of the VF are predominantly marine, but shallow-water and deltaic facies occur in the highest formations. North of the VF, marine conditions were superseded by paralic and continental sedimentation. Erosion, following Variscan tectonism, resulted in the Permian successions generally resting unconformably upon older Palaeozoic rocks. In south-west England a continental succession may extend, with depositional hiatuses, from the latest Carboniferous to the Late Permian and is the most complete Permian succession in Great Britain. However, the position of the Permian–Triassic boundary in the south- west, and elsewhere in the country, is not yet resolved. -

43. on a WELL-MARKED Horizon" of RADIOLARIAN ROCKS ~N the Lowv.~ Cvlm Mms~Aes of Devon, Coa~WALT., and W~St SOM~Aset

Downloaded from http://jgslegacy.lyellcollection.org/ at University of Pennsylvania on January 17, 2016 Vol. 5 i.] RADIOLARIAI~ROCKS IN LOWER CULM I~IEASURES. 609 43. On a WELL-MARKED HORIZOn" of RADIOLARIAN ROCKS ~n the Lowv.~ CVLm MmS~aES of DEvoN, COa~WALT., and W~sT SOM~aSET. By GEORGE JEN~INGS :HINDE, Ph.D., F.G.S., and HOWARD Fox, Esq., F.G.S. (Read June 5th, 1895.) [PLATES XXIII.-XXVIII.] CONTENTS. Page I. Introduction ............................................................ 609 II. Literature relating to the Radiolarian (Codden IIill) Beds 611 lII. Distribution of the Radiolarian Beds ........................... 615 (a) Barnstaple District, N. Devon. (t~) Dulverton, W. Somerset. (c) Ashbrittle, W. Somerset. (d) Holcombo Rogus, Canonsleigh, and Westlelgh, N.E. Devon. (e) Bosc~stle District, C,ornwall. (f) Launeeston Districti"Cornw}fil. (if) Tavistock District, Devon. (/~) Ramshorn Down, near Bovey Tracey, S.E. Devon'. (i) Chudleigh District, Devon: (k) Bishopsteignton, near Teignmouth, S.E. Devon. IV. Mode of Occurrence of the Radiolarian Rocks .................. 627 V. Chemical Composition of the Radiolarian Rocks ............... 629 VI. Microscopic Characters of the Radiolarian Rocks ............... 629 VII. Description of the Radiolaria ...................................... 633 VIII. Description of the other Fossils associated in the same Rocks with the Radiolaria ................................................ 643 (a) Sponges. (b) Corals. (c) Crinoids. (d) Trilobites. By Dr. HENRY WOODWAaD, F.R.S., P.G.S. (e) Brachiopoda. By F. A. BA'ra~a, Esq., IVI.A., F.G.S. (]') Cephalopoda. By G. C. Cl~ICK, Esq., F.G.S. Tables of Fossils (I. & II.). IX. Position of the l~udiol~rian (Codden Hill) Beds in the Lower Culm Series ......................................................... 656 X.