1 THANT, U, Burmese Diplomat, Second Acting Secretary-General Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Threats and Challenges

chapter 3 Threats and Challenges The United Nations has used a broad range of approaches and methods to provide alerts of threats and challenges to the security and welfare of hu- manity including the use of un organs for discussion of potential threats, the presentation of analyses and alerts by the un Secretary-General, the adop- tion of policies and norms, the preventive diplomacy of the un Secretary- General, and the organization of the un Secretariat for early warning and prevention. i Secretary-General Pérez de Cuéllar’s Comprehensive Prevention Strategies and His Case for a Comprehensive Global Watch over Environmental, Economic, Social, Political and Other Factors Affecting International Security Historically, un Secretaries-General have sought to play a role in helping the Organization detect and head off threats and challenges. The first Secretary- General, Trygve Lie, submitted a Ten-point plan to energise the Organization. It was politely received and then ignored. Dag Hammarskjold saw the United Nations as a body that could help advance the development of the developing countries and he helped shape the concepts of conflict prevention and peace- keeping. U Thant sought to develop the role of the United Nations in dealing with humanitarian crises. Kurt Waldheim was a diplomatic helmsman as was Javier Perez de Cuellar. Perez de Cuellar did, however, press hard to develop the capacity of the United Nations for conflict prevention. This was continued by Boutros Boutros-Ghali, whose Agenda for Peace, submitted at the request of the Security Council, sought to mobilise the forces of the Organization for conflict prevention. -

Tarja Halonen: “Toward a Fair Globalization: a Finnish Perspective”

Free for publication on 22 October 2004 at 14h00 local time CHECK AGAINST DELIVERY PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FINLAND TARJA HALONEN: “TOWARD A FAIR GLOBALIZATION: A FINNISH PERSPECTIVE” U THANT DISTINGUISHED LECTURE AT THE UNITED NATIONS UNIVERSITY IN TOKYO OCTOBER 22, 2004 It is a great honour and pleasure for me to give the U Thant Distinguished Lecture here at the United Nations University and celebrate at the same time the United Nations Day. I would like to thank the United Nations University for the excellent work you have done throughout the years. Your contribution to resolve global problems is highly valued. I also would like to thank the Government of Japan for its active participation in the multilateral co-operation and for its generous contribution for the United Nations University. * * * There is a growing understanding of the deep interdependence of security, development, social justice and environmental sustainability. This has been displayed in several recent political commitments within the United Nations: the Millennium Declaration, the Monterrey Consensus on Financing for Development and the Johannesburg Declaration on Sustainable Development. In addition commitments have been made also in other international fora. These are historical global commitments. I even said in this year’s general debate at the United Nations that the Millennium Declaration is by far the most comprehensive and farsighted political commitment ever agreed upon by the United Nations. We now need to turn these commitments into reality, in the spirit of solidarity and within the frames of limited resources of the world. In the Millennium Declaration we challenge ourselves to ensure that globalization becomes a positive force for all the world’s people. -

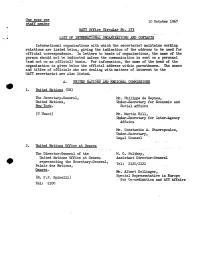

One Copy Per Staff Member GATT Office C I R ^ W Nn. 17^ LIST OF

One copy per 10 Qctober 1Q6? staff member GATT Office Cir^W Nn. 17^ LIST OF IHTERKATIotit"ORGANIZATIONS AND CONTACTS International organizations with which the secretariat maintains working relations are listed below, giving the indication of the address to be used for official correspondence. In letters to heads of organizations, the name of the person should not be indicated unless the communication is sent on a personal (and not on an official) basis. For information, the name of the head of the organization is given below the official address within parentheses. The names and titles of officials who are dealing with matters of interest to the GATT secretariat are also listed. A. UNITED NATIONS AND REGIONAL COMMISSIONS 1. United Nations (UN) The Secretary-General, Mr. Philippe de Seynes, United Nations, Under-Secretary for Economic and New York. Social Affairs (U Thant) Mr. Martin Hill, Under-Secretary for Inter-Agency Affairs Mr. Constantin A. Stavropoulos, Under-Secretary, Legal Counsel 2. United Nations Office at Geneva The Director-General of the M. G. Palthey, United Nations Office at Geneva Assistant Director-General representing the Secretary-General, Tel: 2120/2122 Palais des Nations, Geneva. Mr. Albert Dollinger, (M. P.P. Spinelli) Special Representative in Europe •for Go-ordination and ACC Affairs Tel: 2100 - 2 - United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) The Secretary-General, Mr. P. Judd, United Nations Conference on Trade Director, and Development, Commodities Division Palais des Nations, Geneva. Mr. P. Berthoud, D i n u- u\ Assistant Director, (Dr(n . Raul Prebisch) . _ _ ' nDivision fo r nConference Tel: 34-76 Affairs and External Relations United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) The Executive Director, United Nations Industrial Development Organization, Felderhaus, Wiener Rathhausplatz, Vienna. -

Download Transcript

The Economic Club of New York Some Major Issues before the United Nations _______________________________ His Excellency U Thant Secretary-General, United Nations _______________________________ March 5, 1963 Waldorf-Astoria New York City The Economic Club of New York – His Excellency U Thant – March 5, 1963 Page 1 His Excellency U Thant Secretary-General, United Nations I certainly feel it a privilege to have this opportunity of addressing the Economic Club of New York and I am most grateful to this important organization for the opportunity thus afforded to me. The subject of my talk today is “Some Major Issues before the United Nations.” It is obviously a topic of very wide range and interest, and it will be hardly possible for anyone to deal with it adequately in the space of 25 minutes or so. But I shall attempt to deal with the more important aspects of the major issues confronting the world organization today. As you are no doubt aware, the functions of the United Nations can be broadly classified into three categories: political, economic and social, and trusteeship activities. Before I deal with these main functions, I should like to comment briefly on the United Nations financial problem which, I believe, has been widely publicized, but little understood, over the past few years. The financial difficulties of the organization had their origin in the Organization’s undertaking to maintain peace in the troubled area of the Middle East between Israel and Arab countries, and as a result of its efforts to help the Government of the Congo, amongst other things, to maintain the The Economic Club of New York – His Excellency U Thant – March 5, 1963 Page 2 territorial integrity and the political independence of the Republic of the Congo, to prevent the occurrence of civil war and to maintain law and order in that country. -

Full Transcript

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION BROOKINGS CAFETERIA PODCAST BURMA AT A CROSSROADS Washington, D.C. Friday, December 13, 2019 PARTICIPANTS: Host: FRED DEWS Managing Editor, Podcasts and Digital Projects The Brookings Institution Guests: JONATHAN STROMSETH Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asian Studies Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy, Center for East Asia Policy Studies John L. Thornton China Center THANT MYINT-U Writer, Historian, Conservationist, Public Servant DAVID WESSEL Senior Fellow The Brookings Institution * * * * * 1 P R O C E E D I N G S DEWS: Welcome to the Brookings Cafeteria, the Podcast about ideas and the experts who have them. I'm Fred Dews. I'm joined in the Brookings Podcast Network Studio once again by Senior Fellow Jonathan Stromseth, the Lee Kuan Yew Chair in Southeast Asian Studies here at Brookings. In today's program Jonathan shares another in a continuing series of his conversations with leading experts on issues related to Southeast Asia. Also on today's show, Senior Fellow David Wessel talks about the most significant economic developments of the last decade, including interest rates, life expectancy, inequality and health care. You can follow the Brookings Podcast Network on Twitter @PolicyPodcasts to get information and links to all of our shows. Jonathan, welcome back to the Brookings Cafeteria. STROMSETH: Thank you, Fred. I'm very happy to be here again. DEWS: So, you were on the Brookings Cafeteria recently to talk about your paper in the Global China Series, on China's rise and influence in Southeast Asia, and now we turn to another topic. Can you talk about who you've got for us today? STROMSETH: Yes. -

Dag Hammarskjöld Remembered

It is now fi fty years since Dag Hammarskjöld left the world and the United Nations behind. Yet, with every passing year since his death, his stature grows and his worth along with his contribution becomes more apparent and meaningful. Dag Hammarskjöld Remembered | When Hammarskjöld was at its helm the United Nations was still a relatively young organization, fi nding its way in a post-war world that had entered a new phase, the cold war, for which there was no roadmap. He was a surprise choice as Secretary-General, a so-called “safe” choice as there was little expectation that this former Swedish civil servant would be more than a competent caretaker. Few imagined that Dag Hammarskjöld would embrace his destiny with such passion and independence and even fewer could have foreseen that he would give his life in service to his passion. But as Hammarskjöld himself stated: “Destiny is something not to be desired and not to be avoided – a mystery not con- A Collection Memories of Personal trary to reason, for it implies that the world, and the course of human history, have meaning.” Th at statement sums up his world view. Th is is a volume of memoirs written by people who knew Hammarskjöld. We hope that these memories succeed in imparting to those who never knew or worked with Dag Hammarskjöld the intrinsic fl avour of this unusual, highly intelligent, highly complex individual who believed deeply in the ability of people, especially their ability to aff ect the world in which they live. He once refl ected: “Everything will be all right – you know when? When people, just people, stop thinking of the United Nations as a weird Picasso abstraction and see it as a drawing they made themselves.” Today that advice rings as true as ever. -

Biplove Choudhary, UNDP Time: 15:00 – 17:00

DRR-WG Meeting Meeting Minutes 25th January 2019 Venue: U Thant Conference Room, UNDP Chaired by: Biplove Choudhary, UNDP Time: 15:00 – 17:00 Sr. Agenda Discussions Action Points 1 Introduction of the DRR WG Chair of DRR WG remarks some of the DRR WG‟s accomplishment in members 2018 as followed. Supporting and collaborating with government at Asian Ministerial Conference on Disaster Risk Reduction in Mongolia ( July ) . Organizing the 2nd Earthquake Forum in Yangon ( July) . Nargis 10th year anniversary public outreach campaign in Pathein . Commemoration of International Day for Disaster Reduction 2018 . Government led public Outreach Activities in Nay Pyi Taw . Coordination meeting with government on 2018 flood 2 Reviewing the last meeting It‟s clarified about the number of participation of agencies. If there are changes, minutes Under last agenda AOB session, corrected that IOM recently finished camp agencies will send the management training in Rakhine State. comments by 30th Jan 19. The meeting minutes will be uploaded in MIMU website. 3 IOM DRR project activities in IOM presented about their activities in Rakhine State. For more information, Rakhine and Rakhine DRR IOM has been working in Migration, Trafficking, DRR, Emergency please contact to Aye Working Group Response and Reconstruction, Camp Coordination and Camp Management. Theint Thu, National IOM trained CBDRR Training to 218 village tract/ward administrators in Programme Officer < Rakhine. [email protected] > IOM supported government on development of Township Disaster . To conduct the Management in 4 townships, Emergency Response Contingency Plan for 4 Stocktaking of MAPDRR townships and capacity building trainings. In addition, IOM will also 2017 again among DRR collaborate with UDHRD in Rakhine area. -

Dag Hammarskjöld´S Approach to the United Nations and International Law

1 Dag Hammarskjöld´s approach to the United Nations and international law By Ove Bring Professor emeritus of Stockholm University and the Swedish National Defense College Dag Hammarskjöld, the second Secretary‐General of the United Nations, had a flexible approach to international law. On the one hand, he strongly relied on the principles of the UN Charter and general international law, on the other, he used a flexible and balanced ad hoc technique, taking into account values and policy factors whenever possible, to resolve concrete problems. Hammarskjöld had a tendency to express basic principles in terms of opposing tendencies, to apply a discourse of polarity or dualism, stressing for example that the observance of human rights was balanced by the concept of non‐intervention, or the concept of intervention by national sovereignty, and recognizing that principles and precepts could not provide automatic answers in concrete cases. Rather, such norms would serve “as criteria which had to be weighed and balanced in order to achieve a rational solution of the particular problem”.1 Very often it worked. Dag Hammarskjöld has gone to history as an inspiring international personality, injecting a dose of moral leadership and personal integrity into a world of power politics. He succeeded Trygve Lie as Secretary‐General in April 1953, in the midst of the Cold War, and in addition to East‐West rivalry he was confronted with Third World problems and the agonizing birth of the new Republic of Congo, a tumultuous crisis through which he lost his life in the Ndola air crash in September 1961. -

Angels and Dragons: Program Director Global Issues Asia, the UN, Tel

July 2005 Issues Brief Dr Michael Fullilove Angels and Dragons: Program Director Global Issues Asia, the UN, Tel. +61 2 8238 9040 [email protected] Reform, and the Next Secretary–General Executive Summary The relationship between the UN and Asia can seem unfamiliar and distant. Most of New York’s energy is consumed by the Middle East and Africa rather than Northeast, South and Southeast Asia; the international organisation can seem Atlanticist in orientation. On the other side of the Pacifi c Ocean the strict view of state sovereignty adopted by many Asian capitals leads them to keep the UN at arm’s length. As always, however, the story is more complex: we need to differentiate between the UN’s work in Asia on the one hand, and Asian behaviour at the UN on the other. Since 1945, the UN has contributed to the Asian security order but only at the margins, its security role circumscribed by power politics and Asian approaches to security. By contrast, Asian states have always been keen to exercise their prerogatives in New York, viewing their UN activities as a marker of sovereignty and a source of prestige. The Brief reviews this history and sets out the current stances of the three major regional powers — China, India, and Japan — towards the UN. The next eighteen months will be an important period in UN-Asia relations. A reform process is underway in which Asian states are playing an infl uential role, and Kofi Annan’s successor as Secretary-General is expected to be an Asian. It is argued here that the historical tension in the relationship is evident in contemporary reform discussions, with Asian states more focused on Security Council reform than on those reforms that might conceivably involve the UN more deeply in Asian LOWY INSTITUTE FOR security issues. -

Message from U Thant, Secretary General United Nations, to the ITU World Administrative Radio Conference for Space Telecommunications

Journal Title: Telecommunication Journal Journal Issue: vol. 38 (no. 7), 1971 Article Title: Message from U Thant, Secretary General United Nations, to the ITU World Administrative Radio Conference for Space Telecommunications Author: U Thant Page number(s): pp. 502-503 This electronic version (PDF) was scanned by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) Library & Archives Service from an original paper document in the ITU Library & Archives collections. La présente version électronique (PDF) a été numérisée par le Service de la bibliothèque et des archives de l'Union internationale des télécommunications (UIT) à partir d'un document papier original des collections de ce service. Esta versión electrónica (PDF) ha sido escaneada por el Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la Unión Internacional de Telecomunicaciones (UIT) a partir de un documento impreso original de las colecciones del Servicio de Biblioteca y Archivos de la UIT. (ITU) ﻟﻼﺗﺼﺎﻻﺕ ﺍﻟﺪﻭﻟﻲ ﺍﻻﺗﺤﺎﺩ ﻓﻲ ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﺃﺟﺮﺍﻩ ﺍﻟﻀﻮﺋﻲ ﺑﺎﻟﻤﺴﺢ ﺗﺼﻮﻳﺮ ﻧﺘﺎﺝ (PDF) ﺍﻹﻟﻜﺘﺮﻭﻧﻴﺔ ﺍﻟﻨﺴﺨﺔ ﻫﺬﻩ .ﻭﺍﻟﻤﺤﻔﻮﻇﺎﺕ ﺍﻟﻤﻜﺘﺒﺔ ﻗﺴﻢ ﻓﻲ ﺍﻟﻤﺘﻮﻓﺮﺓ ﺍﻟﻮﺛﺎﺋﻖ ﺿﻤﻦ ﺃﺻﻠﻴﺔ ﻭﺭﻗﻴﺔ ﻭﺛﻴﻘﺔ ﻣﻦ ﻧ ﻘ ﻼً 此电子版(PDF版本)由国际电信联盟(ITU)图书馆和档案室利用存于该处的纸质文件扫描提供。 Настоящий электронный вариант (PDF) был подготовлен в библиотечно-архивной службе Международного союза электросвязи путем сканирования исходного документа в бумажной форме из библиотечно-архивной службы МСЭ. editorial Message from U Thant, Secretary-General United Nations, to the ITU World Administrative Radio Conference for Space Telecommunications Geneva, 7 June 1971 " Any utilization of outer space, for whatever purpose, requires the use of radio waves as the sole link between the earth and the spacecraft or satellite. The radio fre quency spectrum, however, is a limited and increasingly overcrowded natural resource. -

UN Emergency Force Withdrawn from Sinai and Gaza Strip on Egyptian

Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives), Volume 13, June, 1967 Israel, Egyptian, Page 22063 © 1931-2006 Keesing's Worldwide, LLC - All Rights Reserved. The Arab-Israel Crisis.- U.N. Emergency Force withdrawn from Sinai and Gaza Strip on Egyptian Demand. - Egyptian Blockade of Gulf of Aqaba. - Israeli Vessels banned from entering Gulf. - Mobilization in Arab Countries and Israel. - Arab and Soviet Support for Egypt. - U Thant's Mission to Cairo. -International Reactions to Middle East Crisis. The long-standing tension in the Middle East erupted on June 5 in the outbreak of war between Israel and the Arab States, each side accusing the other of responsibility for the commencement of hostilities. As stated in 22062 A and 21817 A, there had been constantly increasing tension on Israel's frontiers since the autumn of 1966 due to the stepping-up of attacks by Arab terrorist organizations, directed in the great majority of eases from Syrian territory. The frequency and intensification of these terrorist attacks, for which the Syrian Government expressed its full support and which the Israeli Government alleged had all been organized by Syria, had led to repeated warnings to Syria by Israeli leaders. As stated in 22062 A, the Israeli Chief of Staff (Major-General Rabin) declared on March 24 that, if these attacks continued, it might become necessary ―to take action against the country from which these infiltrators come.‖ On May 10, according to a report in Le Monde, tire Foreign Minister of Israel (Mr. Eban) had instructed the Israeli ambassadors accredited to the countries represented on the security Council to bring the gravity of the Syro-Israeli frontier situation to the attention of those countries, and to inform them that Israel could not remain inactive in the face of constant aggressions against her territory by Arabs coming from Syria and enjoying the support of the Syrian authorities. -

Dag Hammarskjold and U Thant: the Volute Ion of Their Office M

Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law Volume 7 | Issue 1 1974 Dag Hammarskjold and U Thant: The volutE ion of Their Office M. G. Kaladharan Nayar Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation M. G. Kaladharan Nayar, Dag Hammarskjold and U Thant: The Evolution of Their Office, 7 Case W. Res. J. Int'l L. 36 (1974) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/jil/vol7/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Journal of International Law by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. [Vol. 7: 36 Dag Hammarsk6i1d and U Thant: The Evolution of Their Office* M. G. Kaladharan Nagar Introduction '"(THE UNITED NATIONS is but a reflection of the interna- ,tional community, and in effect its success or failure is the success or failure of the international community." This has been one of the recurring themes in the various public statements and speeches' of U Thant in his ca- pacity as the Secretary-General THE AUTHOR: M. G. KALADHARAN of the United Nations. On the NAYAR (B.Sc., Kerala University; M.A., Panjab University; LL.B., University of other hand, his predecessor Dag Delhi; LL.M., J.S.D., University of Cali- Hammarskj6ld in his Copenha- fornia at Berkeley) is a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Center for the Study of gen speech" of May 2, 1959, Law and Society, University of Califor- pictured the United Nations as nia, Berkeley.