MAREOTIS TH E PTOL EMA IC TOW ERAT AB USIR Photo : Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Renews War on the Meat

-- v. SUGAE-- 96 Degree U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, JUNE 4. Last 24 hours rainfall, .00. Test Centrifugals, 3.47c; Per Ton, $69.10. Temperature. Max. 81; Min. 75. Weather, fair. 88 Analysis Beets, 8s; Per Ton, $74.20. ESTABLISHED JULV 2 1656 VOL. XLIIL, NO. 7433- - HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, TUESDAY, JUNE 5. 1906. PRICE FIVE CENTS. h LOUIS MARKS SCHOOL FUNDS FOSTER COBURN WILL THE ESIDENT SUCCEED BURTON IN KILLED BY RUfl VERY UNITED STATE SENATE RENEWS WAR ON THE AUTO LOW MEAT MEN t - 'is P A Big Winton Machine Less Than Ten Dollars His Message to Congress on the Evils of the , St- .- Over, Crushing Left for Babbitt's 1 Trust Methods Is Turns 4 Accompanied by the -- "1 His Skull. Incidentals, )-- Report of the Commissioner. ' A' - 1 A deplorable automobile accident oc- There are less than ten dollars left jln the stationery and incidental appro- curred about 9:30 last night, in wh'ch ' f. priation for the schol department, rT' Associated Press Cablegrams.) Louis Marks was almost instantly kill- do not know am ' "I what I going to 4-- WASHINGTON, June 5. In his promised message to Congress ed and Charles A. Bon received serious do about it," said Superintendent Bab- (9 yesterday upon the meat trust and its manner of conducting its busi bitt, yesterday. "We pay rents to injury tc his arm. The other occupants the ness, President Kooseveli urged the enactment of a law requiring amount of $1250 a year, at out 1 ! least, stringent inspection of of the machine, Mrs. Marks and Mrs. -

SYNAXARION, COPTO-ARABIC, List of Saints Used in the Coptic Church

(CE:2171b-2190a) SYNAXARION, COPTO-ARABIC, list of saints used in the Coptic church. [This entry consists of two articles, Editions of the Synaxarion and The List of Saints.] Editions of the Synaxarion This book, which has become a liturgical book, is very important for the history of the Coptic church. It appears in two forms: the recension from Lower Egypt, which is the quasi-official book of the Coptic church from Alexandria to Aswan, and the recension from Upper Egypt. Egypt has long preserved this separation into two Egypts, Upper and Lower, and this division was translated into daily life through different usages, and in particular through different religious books. This book is the result of various endeavors, of which the Synaxarion itself speaks, for it mentions different usages here or there. It poses several questions that we cannot answer with any certainty: Who compiled the Synaxarion, and who was the first to take the initiative? Who made the final revision, and where was it done? It seems evident that the intention was to compile this book for the Coptic church in imitation of the Greek list of saints, and that the author or authors drew their inspiration from that work, for several notices are obviously taken from the Synaxarion called that of Constantinople. The reader may have recourse to several editions or translations, each of which has its advantages and its disadvantages. Let us take them in chronological order. The oldest translation (German) is that of the great German Arabist F. Wüstenfeld, who produced the edition with a German translation of part of al-Maqrizi's Khitat, concerning the Coptic church, under the title Macrizi's Geschichte der Copten (Göttingen, 1845). -

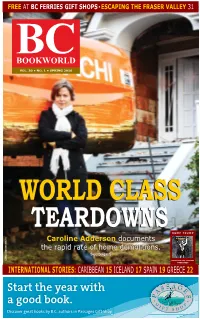

Spring 2016 Volume 30

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS • ESCAPING THE FRASER VALLEY 31 BC BOOKWORLD VOL. 30 • NO. 1 • SPRING 2016 WORLDWORLD CLASSCLASS TEARDOWNSTEARDOWNS DUMP TRUMP Caroline Adderson documents the rapid rate of home demolitions. See page 5 LAURA SAWCHUK PHOTO PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT #40010086 INTERNATIONAL STORIES: CARIBBEAN 15 ICELAND 17 SPAIN 19 GREECE 22 Start the year with a good book. Discover great books by B.C. authors in Passages Gift Shop JOIN US May 20th - 22nd, 2016 Prestige Harbourfront Resort Your coaches Salmon Arm, BC and mentors for 2016: A Festival Robert J. Sawyer $3,000 designed by writers Susan Fox IN CASH for writers Ted Bishop Arthur Slade to encourage, support, Joëlle Anthony inspire and inform. Richard Wagamese Bring your muse Victor Anthony and expect to be Michael Slade Jodi McIsaac welcomed, included Alyson Quinn and thoroughly Jodie Renner entertained. Howard White Alan Twigg Bernie Hucul 3 CATEGORIES | 3 CASH PRIZES | ONE DEADLINE FICTION – MAXIMUM 3,000 WORDS CREATIVE NON-FICTION – MAXIMUM 4,000 WORDS on the POETRY – SUITE OF 5 RELATED POEMS Lake DEADLINE FOR ENTRIES: MAY 15, 2016 Writers’ Festival SUBMIT ONLINE: www.subterrain.ca INFO: [email protected] Find out what these published authors and ENTRY FEE: industry professionals can do for you. Register at: $2750 INCLUDES A ONE-YEAR SUBTERRAIN SUBSCRIPTION! www.wordonthelakewritersfestival.com PER ENTRY YOU MAY SUBMIT AS MANY ENTRIES IN AS MANY CATEGORIES AS YOU LIKE “I have attended this conference for Faculty: the past four years. The information is Alice Acheson -

Food Safety Inspection in Egypt Institutional, Operational, and Strategy Report

FOOD SAFETY INSPECTION IN EGYPT INSTITUTIONAL, OPERATIONAL, AND STRATEGY REPORT April 28, 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cameron Smoak and Rachid Benjelloun in collaboration with the Inspection Working Group. FOOD SAFETY INSPECTION IN EGYPT INSTITUTIONAL, OPERATIONAL, AND STRATEGY REPORT TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE FOR POLICY REFORM II CONTRACT NUMBER: 263-C-00-05-00063-00 BEARINGPOINT, INC. USAID/EGYPT POLICY AND PRIVATE SECTOR OFFICE APRIL 28, 2008 AUTHORS: CAMERON SMOAK RACHID BENJELLOUN INSPECTION WORKING GROUP ABDEL AZIM ABDEL-RAZEK IBRAHIM ROUSHDY RAGHEB HOZAIN HASSAN SHAFIK KAMEL DARWISH AFKAR HUSSAIN DISCLAIMER: The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................... 1 INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ......................................................................... 3 Vision 3 Mission ................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives .............................................................................................................. 3 Legal framework..................................................................................................... 3 Functions............................................................................................................... -

Weeks of Killing State Violence, Communal Fighting, and Sectarian Attacks in the Summer of 2013

The Weeks of Killing State Violence, Communal fighting, and Sectarian Attacks in the Summer of 2013 June 2014 Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 6 Dar Al Shifa (formerly Abdel Latif Bolteya) St., Garden City, Cairo, Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960158 / 27960197 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 Numerous EIPR researchers contributed to this report, but we especially wish to acknowledge those who put themselves at risk to observe events personally, constantly striving to maintain their neutrality amid bloody conflict. We also wish to thank those who gave statements for this report, whether participants in the events, observers or journalists. EIPR also wishes to thank activists and colleagues at other human rights organizations who participated in some joint field missions and/or shared their findings with EIPR. The Weeks of Killing: State Violence, Communal fighting, and Sectarian Attacks in the Summer of 2013 Table of Contents Executive summary .............................................................................................. 5 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 9 Part one: 30 June–5 July: an unprecedented spike in Communal violence 14 30 June: Muqattam .................................................................................... 15 2 July: Bayn -

Severusofantioch

Severus of Antioch His Life and Times Edited by John D’Alton Youhanna Youssef leiden | boston For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Foreword vii Bishop Suriel Preface ix Bishop Mor Malatios Malki Malki Notes on Contributors xi Introduction xiv Severus of Antioch: Heir of Saint John Chrysostom? 1 Pauline Allen Se glorifier de sa ville et de son siège? La grandeur d’Antioche et le mépris des titres chez Sévère le Grand 14 Roger-Youssef Akhrass A Letter from the Orthodox Monasteries of the Orient Sent to Alexandria, Addressed to Severos 32 Sebastian P. Brock The Asceticism of Severus: An Analysis of Struggle in His Homily 18 on the “Forty Holy Martyrs” Compared to the Cappadocians and the Syrians 47 John D’Alton Quotations from the Works of St. Severus of Antioch in Peter of Callinicus’ magnum opus ‘Contra Damianum’ 65 Rifaat Ebied Severus of Antioch and Changing Miaphysite Attitudes toward Byzantium 124 Nestor Kavvadas The Doves of Antioch: Severus, Chalcedonians, Monothelites, and Iconoclasm 138 Ken Parry Severus of Antioch at the Crossroad of the Antiochene and Alexandrian Exegetical Tradition 160 René Roux For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV vi contents Hymns of Severus of Antioch and the Coptic Theotokia 183 Youhanna Nessim Youssef Index 199 For use by the Author only | © 2016 Koninklijke Brill NV Hymns of Severus of Antioch and the Coptic Theotokia Youhanna Nessim Youssef Introduction Severus of Antioch has a special veneration in the Coptic Church.1 In previous studies, we highlighted the role of Severus of Antioch in the Coptic Theotokia,2 especially the homilies 14 and 67 which commemorate a local tradition of the visit of the Virgin Mary to Elisabeth. -

L'épitaphe De Duhëla Sb Iii 6249: Moines Gaïanites Dans Des Monastères Alexandrins

The Journal of Juristic Papyrology Vol. XXVIII, 1998, pp. 55-69 Adam Łajtar Ewa Wipszycka L'ÉPITAPHE DE DUHËLA SB III 6249: MOINES GAÏANITES DANS DES MONASTÈRES ALEXANDRINS 1 est bien connu qu'Alexandrie, dans l'antiquité tardive, était entourée d'un Jdense réseau de monastères. Ils étaient particulièrement nombreux à l'ouest de la ville, sur l'étroite bande de terre (ταινία, en latin taenia) qui séparait le lac Maréotis de la Méditerranée, le long de la route qui menait d'Alexandrie au grand centre de pèlerinage d'Abu Mina et vers la Libye. C'est là que se trou- vaient, parmi d'autres, les célèbres centres monastiques Pempton, Enaton (ou Ennaton), Oktokaidekaton et Eikoston, ainsi appelés parce qu'ils étaient situés, respectivement, près de la cinquième, de la neuvième, de la dix-huitième et de la vingtième pierre milliaire du cursus publicus.1 Les centres monastiques de la taenia alexandrine sont connus surtout grâce à des textes littéraires et para-littéraires. La documentation papyrologique est à peu près inexistante, ce qui est normal pour une localité de la Basse Egypte. On dispose en revanche de données archéologiques et, pour un centre monastique qui a dû être situé près de la localité moderne de Duhëla, d'un groupe im- portant d'inscriptions. Ad-Duhëla se trouve à une dizaine de km à l'ouest du centre d'Alexandrie, à la hauteur d'Agami, à peu près à l'endroit de l'antique Plinthinè. C'était jadis un village, mais depuis longtemps, c'est un faubourg d'Alexandrie. Au début du XXe siècle, dans cette localité, à 500 m au sud-est de la gare de chemin de 1 Au sujet de ces centres, voir les articles de J. -

Jean GASCOU Professeur Émérite De Papyrologie À L'université De Paris-Sorbonne Ancien Directeur De L'institut De Papyrologie

1 Jean GASCOU Professeur émérite de papyrologie à l'université de Paris-Sorbonne ancien directeur de l'institut de papyrologie Curriculum Vitae Né le 16 mai 1945 à Cambrai (Nord) Elève de l'Ecole Normale Supérieure de la rue d'Ulm (1965/70) Agrégé d'Histoire (1971) Pensionnaire de la Fondation Thiers (1972/73) Membre scientifique de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (1973/79) Attaché puis chargé de recherche au CNRS - URA 990 - Institut de papyrologie de la Sorbonne (1979/88) Doctorat d'Etat (Université Strasbourg II, 1986) Professeur des universités (papyrologie-langue grecque) à l'Université Marc Bloch-Strasbourg II (1988- 2006) Membre senior de l'Institut Universitaire de France (1995/2005) Directeur de l'UMR 7044 (2001-2006) Professeur de papyrologie à l'université de Paris-Sorbonne, directeur de l'institut de papyrologie (2006-2014) Professeur émérite Paris-Sorbonne (2014- ) Publications Ouvrages – Un codex fiscal Hermopolite (P.Sorb. II 69), Atlanta, 1994 (thèse de doctorat d'Etat publiée avec le concours de l'USHS, legs Louise Weiss, de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne, et du CNRS). Prix Schlumberger de l'Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres ; prix de l'Association pour l'encouragement des études grecques. Recensions : G. Dagron, CRAI 1995, p. 376-377, J. Whitehorne, Bryn Mawr Classical Rewiew 6, 1995, p. 406-408, J. D. Thomas, Tyche 11, 1996, p. 267-269, A. Blanchard, Revue des études grecques , 110, 1997, p. 659-661, I.F.Fikhman, Chronique d'Egypte 72, 1997, p. 161-168, F. Mitthof, Gnomon 71, 1999, p. 134-139, Ph. Luisier, Orientalia Christiana Periodica 65, 1999, p. -

Couverture BIA 53

Bulletin d'Information Archéologique BIALIII le rêve de Reeves ! Collège de France Institut français Chaire "Civilisation de l'Égypte pharaonique : d'archéologie orientale archéologie, philologie, histoire" Bulletin d'Information Archéologique BIAwww.egyptologues.net LIII Janvier - Juin 2016 Le Caire - Paris 2016 Bulletin d’Information Archéologique REVUE SEMESTRIELLE n° 53 janvier / juin 2016 Directeur de la publication Système de translittération Nicolas GRIMAL des mots arabes [email protected] Rédaction et coordination Emad ADLY [email protected] consonnes voyelles IFAO Ambafrance Caire û و ,î ي ,â ا : q longues ق z ز ‘ ء S/C Valise diplomatique 13, rue Louveau F-92438 Chatillon k brèves : a, i, u ك s س b ب http://www.ifao.egnet.net l diphtongues : aw, ay ل sh ش t ت rue al-Cheikh Ali Youssef ,37 B.P. Qasr al-Aïny 11562 m م s ص th ث .Le Caire – R.A.E Tél. : [20 2] 27 97 16 37 Fax : [20 2] 27 94 46 35 n ن Dh ض G ج Collège de France h autres conventions هـ t ط H ح Chaire "Civilisation de l’Égypte pharaonique : archéologie, (w/û tæ’ marbºta = a, at (état construit و z ظ kh خ "philologie, histoire http://www.egyptologues.net y/î article: al- et l- (même devant les ى ‘ ع D د 52, rue du Cardinal Lemoine “solaires”) F 75231 Paris Cedex 05 غ ذ Tél. : [33 1] 44 27 10 47 Fax : [33 1] 44 27 11 09 Z gh f ف r ر Remarques ou suggestions [email protected] Les articles ou extraits d’articles publiés dans le BIA et les idées qui peuvent s’y exprimer n’engagent que la responsabilité de leurs auteurs et ne représentent pas une position officielle de la Rédaction. -

MES ANNÉES EN ÉGYPTE Avec Photos .Pdf

MES ANNÉES EN ÉGYPTE Notre histoire en Egypte, racontée par Joseph Hakim. Les photos ont été insérées par Elie Lichaa. L’ÉGYPTE ET SES JUIFS QUE J’AI CONNUS. Je suis né à Alexandrie en 1931 - j’ai quitté l’Égypte en Juin 1957 après la guerre de Suez - “Mivtsa’a Kadeche”. Durant cette période et bien avant 1931 les Juifs en Égypte -- ou les Juifs d’Égypte -- passèrent par diverses situations -- bonnes ou mauvaises selon lescirconstances et notamment à la suite de l’idéologie de Hassan -- El-Banna (circa 1925) pour arriver aux pires moments à partir de fin Octobre 56. Hassan El Banna (1906-1949), fondateur des Frères Musulmans Published by the Historical Society of Jews From Egypt. All Rights Reserved Page 1 Plusieurs livres ont été écrits à ce sujet, surtout ceux de Mme Bat-Yaor que je recommande chaleureusement. L’attitude anti-juive s’intensifia davantage vers la fin de la seconde guerre mondiale toujours par l’influence des Frères Musulmans et de Cheikh El-Azhar qui considéraient seuls les Musulmans comme égyptiens de droit! Les Coptes étaient un fait accompli -- à leurs yeux -- une population chrétienne de facto contre laquelle ni les Frères ni El-Azhar n’avaient encore de solution! En même temps que les “Frères” -- des organisations nazies jubilaient avec l’arrivée des Allemands à Al-Alamein aux portes d’Alexandrie -- le Roi Farouk lui-même ne souhaitait pas moins remplacer l’occupation anglaise par celle des hommes d’Adolf Hitler... Roi Farouk (1920-1965) régna du 28.4.1936 au 26.7.1952 La population juive en Égypte d’après les recensements comptait en 1897 25.000 dont 1.000 Cairotes. -

Exodus in Syriac

Exodus in Syriac Jerome A. Lund Three translations of the Book of Exodus into Syriac are known: the Peshitta,1 the translation of Paul of Tella termed by present-day scholars the Syrohexa- pla,2 and the translation of Jacob of Edessa.3 The Peshitta translates a Hebrew text that is situated in the proto-Masoretic textual stream. By contrast, Paul of Tella rendered the Greek text into Syriac to give Syrian church leaders and scholars a means of approaching the Greek for comparative purposes. He incor- porated hexaplaric annotations into the text and marginal notes, so that his translation constitutes a valuable witness not only to the Old Greek translation, but also to the Greek versions of Aquila, Symmachos, and Theodotion. Jacob of Edessa utilized the Peshitta as his base text, while incorporating elements of the Greek Bible both through direct translation and from the Syrohexapla.4 From his study of Isaiah, Andreas Juckel has suggested that Jacob of Edessa sought “to adjust the Peshitta to the Greek as much as necessary, and to adopt the 1 Marinus D. Koster prepared the book of Exodus for the Leiden scientific edition of the Peshitta, The Old Testament in Syriac According to the Peshitta Version—Part i, 1. Preface, Genesis—Exodus (Leiden: Brill, 1977). The earliest attestation of the term “Peshitta” ( =I%"Kܐ ; “simple,” “straightforward”) comes from the ninth century theologian Moshe bar Kepha. The term was used to distinguish the earlier translations of the Bible from the seventh century translations (Sebastian P. Brock, The Bible in the Syriac Tradition [gh 7; rev. -

The Cult of Saint Thecla

OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES General Editors Gillian Clark Andrew Louth THE OXFORD EARLY CHRISTIAN STUDIES series includes scholarly volumes on the thought and history of the early Christian centuries. Covering a wide range of Greek, Latin, and Oriental sources, the books are of interest to theologians, ancient historians, and specialists in the classical and Jewish worlds. Titles in the series include: Clement of Alexandria and the Beginnings of Christian Apophaticism Henny Fiskå Hägg (2006) The Christology of Theodoret of Cyrus Antiochene Christology from the Council of Ephesus (431) to the Council of Chalcedon (451) Paul B. Clayton, Jr. (2006) Ethnicity and Argument in Eusebius’ Praeparatio Evangelica Aaron P. Johnson (2006) Union and Distinction in the Thought of St Maximus the Confessor Melchisedec Törönen (2007) Contextualizing Cassian Aristocrats, Asceticism, and Reformation in Fifth-Century Gaul Richard J. Goodrich (2007) Ambrosiaster’s Political Theology Sophie Lunn-Rockliffe (2007) Coptic Christology in Practice Incarnation and Divine Participation in Late Antique and Medieval Egypt Stephen Davis (2008) Possidius of Calama A Study of the North African Episcopate in the Age of Augustine Erica T. Hermanowicz (2008) Justinian and the Making of the Syrian Orthodox Church Volker L. Menze (2008) The Christocentric Cosmology of St Maximus the Confessor Torstein Theodor Tollefsen (2008) Augustine’s Text of John Patristic Citations and Latin Gospel Manuscripts H. A. G. Houghton (2008) Hilary of Poitiers on the Trinity From De Fide to De Trinitate Carl L. Beckwith (2008) The Cult of Saint Thecla: A Tradition of Women’s Piety in Late Antiquity Stephen J. Davis 3 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.