Aice-Bs2016edinburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EG-Helwan South Power Project Raven Natural Gas Pipeline

EG-Helwan South Power Project The Egyptian Natural Gas Company Raven Natural Gas Pipeline ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT June 2019 Final Report Prepared By: 1 ESIA study for RAVEN Pipeline Pipeline Rev. Date Prepared By Description Hend Kesseba, Environmental I 9.12.2018 Specialist Draft I Anan Mohamed, Social Expert Hend Kesseba, Environmental II 27.2.2019 Specialist Final I Anan Mohamed, Social Expert Hend Kesseba, Environmental Final June 2019 Specialist Final II Anan Mohamed, Social Expert 2 ESIA study for Raven Pipeline Executive Summary Introduction The Government of Egypt (GoE) has immediate priorities to increase the use of the natural gas as a clean source of energy and let it the main source of energy through developing natural gas fields and new explorations to meet the national gas demand. The western Mediterranean and the northern Alexandria gas fields are planned to be a part from the national plan and expected to produce 900 million standard cubic feet per day (MMSCFD) in 2019. Raven gas field is one of those fields which GASCO (the Egyptian natural gas company) decided to procure, construct and operate a new gas pipeline to transfer rich gas from Raven gas field in north Alexandria to the western desert gas complex (WDGC) and Amreya Liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) plant in Alexandria. The extracted gas will be transported through a new gas pipeline, hereunder named ‘’the project’’, with 70 km length and 30’’ inch diameter to WDGC and 5 km length 18” inch diameter to Amreya LPG. The proposed project will be funded from the World Bank(WB) by the excess of fund from the south-helwan project (due to a change in scope of south helwan project, there is loan saving of US$ 74.6 m which GASCO decided to employ it in the proposed project). -

The Renews War on the Meat

-- v. SUGAE-- 96 Degree U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, JUNE 4. Last 24 hours rainfall, .00. Test Centrifugals, 3.47c; Per Ton, $69.10. Temperature. Max. 81; Min. 75. Weather, fair. 88 Analysis Beets, 8s; Per Ton, $74.20. ESTABLISHED JULV 2 1656 VOL. XLIIL, NO. 7433- - HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, TUESDAY, JUNE 5. 1906. PRICE FIVE CENTS. h LOUIS MARKS SCHOOL FUNDS FOSTER COBURN WILL THE ESIDENT SUCCEED BURTON IN KILLED BY RUfl VERY UNITED STATE SENATE RENEWS WAR ON THE AUTO LOW MEAT MEN t - 'is P A Big Winton Machine Less Than Ten Dollars His Message to Congress on the Evils of the , St- .- Over, Crushing Left for Babbitt's 1 Trust Methods Is Turns 4 Accompanied by the -- "1 His Skull. Incidentals, )-- Report of the Commissioner. ' A' - 1 A deplorable automobile accident oc- There are less than ten dollars left jln the stationery and incidental appro- curred about 9:30 last night, in wh'ch ' f. priation for the schol department, rT' Associated Press Cablegrams.) Louis Marks was almost instantly kill- do not know am ' "I what I going to 4-- WASHINGTON, June 5. In his promised message to Congress ed and Charles A. Bon received serious do about it," said Superintendent Bab- (9 yesterday upon the meat trust and its manner of conducting its busi bitt, yesterday. "We pay rents to injury tc his arm. The other occupants the ness, President Kooseveli urged the enactment of a law requiring amount of $1250 a year, at out 1 ! least, stringent inspection of of the machine, Mrs. Marks and Mrs. -

Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 in Collaboration With

know more.. Egypt Real Estate Trends 2018 In collaboration with -PB- -1- -2- -1- Know more.. Continuing on the momentum of our brand’s focus on knowledge sharing, this year we lay on your hands the most comprehensive and impactful set of data ever released in Egypt’s real estate industry. We aspire to help our clients take key investment decisions with actionable, granular, and relevant data points. The biggest challenge that faces Real Estate companies and consumers in Egypt is the lack of credible market information. Most buyers rely on anecdotal information from friends or family, and many companies launch projects without investing enough time in understanding consumer needs and the shifting demand trends. Know more.. is our brand essence. We are here to help companies and consumers gain more confidence in every real estate decision they take. -2- -1- -2- -3- Research Methodology This report is based exclusively on our primary research and our proprietary data sources. All of our research activities are quantitative and electronic. Aqarmap mainly monitors and tracks 3 types of data trends: • Demographic & Socioeconomic Consumer Trends 1 Million consumers use Aqarmap every month, and to use our service they must register their information in our database. As the consumers progress in the usage of the portal, we ask them bite-sized questions to collect demographic and socioeconomic information gradually. We also send seasonal surveys to the users to learn more about their insights on different topics and we link their responses to their profiles. Finally, we combine the users’ profiles on Aqarmap with their profiles on Facebook to build the most holistic consumer profile that exists in the market to date. -

A Catalogue of Coleoptera Specimens with Potential Forensic Interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum Collection

ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA Vol. 25, 2016 A catalogue of Coleoptera specimens with potential forensic interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection Dimaki Maria Goulandris Natural History Museum, 100 Othonos St. 14562 Kifissia, Greece Anagnou-Veroniki Maria Makariou 13, 15343 Aghia Paraskevi (Athens), Greece Tylianakis Jason Zoology Department, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/eh.11549 Copyright © 2017 Maria Dimaki, Maria Anagnou- Veroniki, Jason Tylianakis To cite this article: Dimaki, M., Anagnou-Veroniki, M., & Tylianakis, J. (2016). A catalogue of Coleoptera specimens with potential forensic interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection. ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA, 25(2), 31-38. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.12681/eh.11549 http://epublishing.ekt.gr | e-Publisher: EKT | Downloaded at 27/12/2018 06:22:38 | ENTOMOLOGIA HELLENICA 25 (2016): 31-38 Received 15 March 2016 Accepted 12 December 2016 Available online 3 February 2017 A catalogue of Coleoptera specimens with potential forensic interest in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection MARIA DIMAKI1’*, MARIA ANAGNOU-VERONIKI2 AND JASON TYLIANAKIS3 1Goulandris Natural History Museum, 100 Othonos St. 14562 Kifissia, Greece 2Makariou 13, 15343 Aghia Paraskevi (Athens), Greece 3Zoology Department, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch, New Zealand ABSTRACT This paper presents a catalogue of the Coleoptera specimens in the Goulandris Natural History Museum collection that have potential forensic interest. Forensic entomology can help to estimate the time elapsed since death by studying the necrophagous insects collected on a cadaver and its surroundings. In this paper forty eight species (369 specimens) are listed that belong to seven families: Silphidae (3 species), Staphylinidae (6 species), Histeridae (11 species), Anobiidae (4 species), Cleridae (6 species), Dermestidae (14 species), and Nitidulidae (4 species). -

Report 2019 Bank Audi Annual Report 2019

2019 ANNUAL REPORT EGYPT 1 BANK AUDI ANNUAL REPORT 2019 BANK AUDI ANNUAL REPORT 2019 BANK AUDI “S.A.E.” INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT AND FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31 December 2019 ANNUAL REPORT 2019 BANK AUDI “S.A.E.” BANK AUDI “S.A.E.” Annual Report 2019 01 OVERVIEW 01 OVERVIEWA. The Chairman’s Statement.............................................................. 8 B. CEO,A. The Managing Chairman’s Director's Statement............................................................... Statement............................................. 10 6 C. B.Strategic Bank Audi Direction sae Strategic & Values Direction of Bank & AudiValues................................... sae.............................. 1210 D. C.Overview Bank Audi of Group...............................................................................Bank Audi Group.......................................................... 1310 E. KeyD. Bank Financial Audi sae highlights Key Financial of Bank Highlights......................................... Audi sae.................................. 1411 F. GlobalE. The Egyptian & Regional Economy Economy in 2019....................................................... in 2019............................................ 1412 G. The Egyptian Economy in 2019.................................................... 16 022 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CORPORATEA. Board of Directors............................................................................. GOVERNANCE 16 02 B. Governance....................................................................................... -

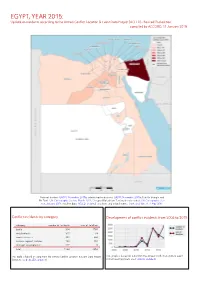

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Alexandria, a Place I Remember

AAHA = Amicale Alexandrie Hier et Aujourd'hui George PSAROS Return to Alexandria (17-28 November 2004) “The best way of seeing it is to wander aimlessly about” - E.M.Forster Cahier no 47 October 2005 Sandro Manzoni, chemin de Planta 31, 1223 Cologny, Suisse Return to Alexandria (17-28 November 2004) Cahier AAHA no 47 I left Alex in 1952 to attend university in England. Now I was returning with my wife Annette who had been listening to me, my relatives, and assorted Old Victorians wailing about La Belle Époque in Alex for nearly forty years. Annette is very patient and very polite. Our departure from London was not straightforward. Having duly proceeded to the departure gate for our Lufthansa flight to Frankfurt we were informed 15 minutes before take-off that our plane was not going anywhere for the foreseeable future. The luggage had to be reclaimed and we queued for 3 hours to get rescheduled to Athens by BA next day. We befriended an anxious Mrs. Suliman who was also hoping to get to Alexandria some day. So our first night away from home was spent in London at one of the living machines they call hotels. Next morning we set off again and duly arrived at Athens airport where Mrs. Suliman insisted I call Delta Hotel on her mobile. Just as well, because Lufthansa had failed to notify anyone in Alex that we had missed the Frankfurt connecting flight because of the cancellation of their London flight. Our flights cost £ 640.25. We disembarked from our Egyptair jet at Nouzha and I felt immediately that this trip was going to be a success after all. -

Asset-Based Development: Success Stories from Egyptian Communities

Asset-Based Development: Success Stories from Egyptian Communities A Manual for Practitioners English translation of original document, published in Arabic by the Center for Development Services in Cairo, Egypt 2005 CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 5 Case Studies 7 Success Breeds Success 8 A Creative Community Based Composting Initiative 13 Moving Beyond Conventional Charity Work 18 Building Community Capacity 23 The Transformative Power of Art 29 Fan Sina 34 Linking Community and Government for Development 39 Peer-to-Peer Learning through the Living University 45 Bridging Gaps between Communities and Institutions 50 Rising from Modest Roots through Partnership 56 Mobilizing, Renewing and Building Assets: Methods, Tools, and Strategies 61 Identifying and Mobilizing Assets 63 Appreciative Interviewing and Analyzing Community Success 63 Mapping and Organizing 64 · Appreciative Interviewing 65 · Community Analysis of Success 67 · Positive Deviance 69 · Identifying Individual Skills: Hand, Heart, Head 71 · Mapping Community Groups or Associations 74 · Capacity Inventories 76 Linking Assets to Opportunities 78 Institutional Mapping and the Leaky Bucket 78 · Linking, Mobilizing & Organizing 79 · Mapping Institutions 81 · Leaky Bucket 84 The Role of the Intermediary 88 Fostering Broad-Based Leadership 89 Identifying “Gappers” 90 Helping Communities to Build Assets 91 Helping Communities to Link Assets to External Opportunities 92 Leading by Stepping Back 93 Tracking the Process as it Unfolds 93 Extended Case Studies 94 Success Breeds -

QIZ Ref. Sector Location Company Name Address Contact Name Title Tel Fax Mobile Email

QIZ Ref. Sector Location Company Name Address Contact Name Title Tel Fax Mobile Email Textile & Egyptian Company for Trade & Suez Canal St. Moharam Bek, El-Bar El-Kibly, Vice 3 Alexandria Salem Mohamed Salem 03-3615748 03-3618004 0122-2166302 [email protected] RMG Industry (SOGIC) Industrial Area President Textile & Shoubra El The Modern Egyptian Spinner 3 Montaser El Gabalawy St., Bahteem Old misrspain@misrsp 5 Essam Abd El Fattah Lawyer 02-2201107 02-2211184 0122-3788634 RMG Kheima (Ghazaltex) S.A.E Road, Shoubra El Kheima ain.com Textile & 120 Osman Basha Street, EL-Bar El-Kibly, Sherine Issa Hamed Managing babycoca1@babyc 8 Alexandria Baby Coca for Clothing 03-3815052 03-3815054 0122-2142042 RMG Semouha Ellish Director oca.com.eg Textile & Shoubra El Misr Company for Industrial Number 64, 15th May Road, Shoubra El- Mohamed Wadah Vice wadah@misrgrou 9 02-2208880 02-2211220 0122-7495992 RMG Kheima Investments , Private Free Zone Kheima, Kalyoubia Shamsi President p.com Textile & Misr El Ameria Spinning & Desert Road Alex/Cairo ( KM 23 ), Mohamed Ahmed Accountant export@misramre 10 Alexandria 03-2020395 03-2020390 0100-6123011 RMG Weaving Co. Petrochemical Road, Alexandria Mohamed Hegazy at Export Dep ya.com Textile & Obour City - Industrial Zone B,G Block No. Hosam El-Din General [email protected] 11 El Obour El Magmoua El Togaria 02-42157431 02-42155526 0111-7800123 RMG 22009 - Plot Industrial 2A Mohamed Mohab Manager om Textile & Shoubra El 2 El Mallah Street, Bigam Road, Shoubra El- Saber Ibrahim El Director In info@elmallahgro 12 El Mallah -

País Região Cidade Nome De Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria

País Região Cidade Nome de Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria Adrar Timimoun Gourara Hotel Timimoun, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hotel Hammamet Ain Benian RN Nº 11 Grand Rocher Cap Caxine , 16061, Aïn Benian, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hôtel Hammamet Alger Route nationale n°11, Grand Rocher, Ain Benian 16061, Algeria 16061 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Safir Alger 2 Rue Assellah Hocine, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Samir Hotel 74 Rue Didouche Mourad, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Albert Premier 5 Pasteur Ave, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Suisse 06 rue Lieutenant Salah Boulhart, Rue Mohamed TOUILEB, Alger 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Aurassi Hotel El-Aurassi, 1 Ave du Docteur Frantz Fanon, Alger Centre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre ABC Hotel 18, Rue Abdelkader Remini Ex Dujonchay, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Space Telemly Hotel 01 Alger, Avenue YAHIA FERRADI, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hôtel ST 04, Rue MIKIDECHE MOULOUD ( Ex semar pierre ), 4, Alger Ctre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 24 Rue Nezzar Kbaili Aissa, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Oran Center 44 Rue Larbi Ben M'hidi, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Es-Safir Hotel Rue Asselah Hocine, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 22 Rue Hocine BELADJEL, Algiers, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre -

Housing & Development Bank Group

INDEX Notes to the Separate Housing & Development Bank Financial Statements Vision & Mission 4 Notes to the Separate Financial Statements 56 Shareholding Structure 6 Financial Highlights 8 Chairman’s Forward 10 Head Office and Branches Head Office and Branches 117 Management of the Bank Board of Directors 18 Housing & Development Heads of Divisions, Regionals and Zones 22 Bank Group Bank’s Committees 26 Auditors’ Report 138 Board Statement 30 Consolidated Balance Sheet 140 Consolidated Income Statement 142 Consolidated Cash Flows Statement 144 Separate Financial Reports Consolidated Changes in Shareholders’ Statement 146 Independent Auditors’ Report 42 Separate Balance Sheet 44 Separate Income Statement 46 Separate Cash Flows Statement 48 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements Separate Changes in Shareholders’ Equity Statement 50 Profit Dividends Statement 52 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements 150 2 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2018 3 Vision & Mission HDBank Vision HDBank Mission To be within the top ten ranked commercial banks in the Striving to excel in providing both banking and real banking sector, while working on sustaining the current estate services as well as mortgage while continuously high operating efficiency. upgrading our human capital to reach a distinguished level of services for our clients to serve their needs and aspirations of the shareholders. 4 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report 2018 5 Shareholding Structure as at 31/12/2018 Share per unit Total share Government Institutions Public Sector Institutions -

The Role of Social Responsibility in Protecting the Environment – a Case of the Petrochemical Companies in Alexandria Governor

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/2631-3561.htm Role of social The role of social responsibility responsibility in protecting the environment – a case of the petrochemical companies in Received 17 April 2019 Alexandria Governorate Revised 21 July 2019 Rasha Kamal El-Deen El-Mallah Accepted 8 August 2019 Financial and Administrative Affairs, General Authority For Literacy and Adult Education, Alexandria, Egypt Alia Abd el Hamid Aref Public Administration, FEPS, Cairo, Egypt and Public Administration, Faculty of Economics and Political Science, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt, and Sherifa Sherif Faculty of Economics and Political Science, Cairo University, Giza, Egypt Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is as follows: First, understanding the nature of the relationship between corporate adoption of the concept of societal responsibility [availability of environmental awareness, clear vision of the impact of societal responsibility on financial performance, managers informing employees of the latest developments in societal responsibility programs, managers’ response to their corporate social responsibility (CSR) proposals] in the form of an annual report that supports the success of the company’s objectives, the company’s management encourages employees to participate collectively in societal responsibility programs and to protect the environment from pollution in the petrochemical industry. Second, understand the nature of the relationship between the