The Equal Rights Trust Uganda Anti Homosexuality Bill Opinion.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Uganda Joint Statement

JOINT STATEMENT ON THE OCCASION OF THE VISIT TO UGANDA OF THE VICE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, Mr MOHAMMAD HAMID ANSARI FROM 21 – 23 FEBRUARY 2017 The Vice President of India, Mr Mohammad Hamid Ansari paid an official visit to Uganda from 21st to 23rd February 2017. The Vice President was accompanied by his spouse Mrs Salma Ansari and a delegation comprising Minister of State, Mr Vijay Sampla, four Members of Parliament, other Senior Government Officials and a business delegation. 2. Vice President Ansari met and held bilateral discussions with President of the Republic of Uganda Mr Yoweri Museveni, at State House, Entebbe on Wednesday 22nd February 2017. Vice President Ansari also met the Vice President of Uganda Mr Edward Ssekandi, Speaker of Uganda Ms Rebecca Alitwala Kadaga and Prime Minister Mr Ruhakana Rugunda. The Vice President addressed a business event jointly organised by the Private Sector Foundation of Uganda and Federation of India Chambers of Commerce and Industry. VP Ansari visited the Source of the Nile in Jinja and paid floral tribute at the bust of Mahatma Gandhi. VP also interacted with the Indian Community in Uganda. 3. During the discussions, Vice President Ansari and President Museveni acknowledged the long-standing excellent historical relations that exist between Uganda and India. Both sides acknowledged the huge potential in India-Uganda bilateral relations and re-affirmed the mutual desire to strengthen economic, diplomatic, military, technical, educational, scientific and cultural cooperation between India and Uganda. In this regard, it was acknowledged that there were an estimated over 26000 persons of Indian origin in Uganda who contribute immensely towards Uganda’s national economy. -

An Analysis of Uganda's Truth Commission

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by YorkSpace The Politics of Acknowledgement: An Analysis of Uganda’s Truth Commission Joanna R. Quinn1 Doctoral Candidate Department of Political Science McMaster University YCISS Working Paper Number 19 March 2003 The YCISS Working Paper Series is designed to stimulate feedback from other experts in the field. The series explores topical themes that reflect work being undertaken at the Centre. 1 I wish to thank Dr. Rhoda Howard-Hassmann of McMaster University for our on-going dialogue on this subject. I also gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. William Coleman and the Institute on Globalization and the Human Condition of McMaster University, and of the International Development Research Centre in Ottawa, Canada. In the aftermath of a period of gross atrocity at the hands of the state, the restoration of the political and social fabric of a country is a pressing need. In the case of Uganda from the mid-1960s forward, this need was particularly real. Almost since the country had gained independence from Britain in 1962, a series of brutal governmental regimes had ransacked the country, and had viciously dealt with its inhabitants. Nearly thirty years of mind-numbing violence, perpetrated under the regimes of Idi Amin and Milton Obote, culminated in a broken society. Where once had stood a capable people, able to provide for themselves on every level, now was found a country whose economic, political, and social systems were seriously fractured. Under both Obote and Amin, as well as the transitional governments in place between and immediately following these regimes, democracy and the rule of law had been suspended. -

Museveni, Mbabazi, Barya Nominated

2 NEW VISION, Wednesday, November 4, 2015 ELECTION 2016 Mbabazi shaking hands with Kiggundu during nomination Baryamureeba hands documents to Kiggundu at Namboole Museveni, Mbabazi, Barya nominated By Moses Walubiri Baryamureeba nominated and Pascal Kwesiga At 10:55am, 17 minutes after making his entrance, Baryamureeba too got The faces of candidates to appear nominated. on the ballot paper for next year’s The academic-turned-politician presidential elections became clearer said he intends to revamp Uganda’s yesterday, following the nomination health and education sectors an of President Yoweri Museveni and integral component of his campaign. former premier, Amama Mbabazi. “You cannot think of development The other candidate nominated when you have an ailing health by the Electoral Commission (EC) sector, and broken education sector,” was former Makerere University Baryamureeba noted, saying Mbabazi vice-chancellor, Prof. Venansius and Museveni are the same. Baryamureeba. “If Mbabazi and Museveni were Although the EC expected five of bishops, they would be retired clerics the 10 candidates that had satisfied now. I am just 46 years. This country the requirement of collecting needs someone of my energy and signatures of not less than 100 calibre,” he added. voters in at least two thirds of all the Mbabazi and Baryamureeba districts in Uganda, only four turned picked the signs of a chair and a up. clock respectively which they will “By the powers entrusted in me use during their campaigns since by the Electoral Commissions Act, they are contesting as independent I declare Yoweri Kaguta Museveni candidates. a duly nominated candidate,” EC However, Charles Bbale Lwanga of chairman, Dr. -

Uganda Relations

India-Uganda Relations The bilateral relations between India and Uganda are characterised by historical cultural linkages, extensive economic and trade interests, and a convergence on major bilateral and international issues. A 27000+ Indian/PIO population in Uganda, a bilateral trade of nearly US$ 1.3 billion, a steady surge of Indian investments making India consistently one of the top investors in Uganda, capacity building training programmes and institutions, and a common and deep respect for universal values like democracy and peace reinforce the architecture of India-Uganda bilateral relations. Trade and economic interests brought several Indians to the shores of East Africa as early as the 17th century in dhows laden with their wares. Eventually a number of Indians settled in East Africa, and many made Uganda their home. India's freedom struggle inspired the early Ugandan activists to fight colonization and Uganda eventually achieved Independence in 1962. India established it diplomatic presence in Uganda in 1965. Except for the era of Idi Amin’s reign in early 70's when nearly 55,000 Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) and 5000 Indian nationals were expelled and their properties confiscated, relations between the two countries have since been cordial. The anti-Indian policies of Amin were reversed when the current President YoweriKagutaMuseveni came to power in 1986. The current Government’s progressive policies ensured that the India-Uganda relations were restored to erstwhile levels. Uganda remains an important partner in Africa. India and Uganda closely cooperate at regional and international fora. Exchange of High-Level Visits: From India: • Prime Minister Shri. -

Africa Confidential

www.africa-confidential.com 4 April 2003 Vol 44 No 7 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL UGANDA/RWANDA 2 UGANDA Soccer war, Congo war In the phoney war, the score was The great U-turn nil-nil as Rwanda and Uganda President Museveni calls for the freeing of parties and the chance of played a qualifier in Africa’s Cup of a third term at the top Nations soccer tournament last It was the sharpest of U-turns. President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, who has vehemently defended his weekend in Kigali. In the real war in eastern Congo-Kinshasa, ‘no-party system’ of government since he won power in 1986, now wants to lift the ban on multi-party Kampala and Kigali back rival politics. He told delegates at an apprehensive congress of the ruling National Resistance Movement at militias and may be preparing for Kyankwanzi, north of Kampala, on 26 March, that they should accommodate those politicians who had another direct confrontation over persuaded ‘about 20 per cent’ of Ugandans to vote against his no-party system. The NRM would remain Congo’s mineral riches. unchanged, a broad church: ‘Those who want to experiment again with political parties can do so alongside the Movement, which should maintain its present identity’. So the no-party system (with its KENYA 3massive state subventions) is to compete with others in the presidential election due in 2006. The change of heart is more pragmatic than ideological. The NRM’s middle ranks are increasingly Victory is not enough calling for political liberalisation and modernisation. They also want more power within the Movement Two interlinked questions gnaw at over its ruling clique, who have been conspicuously enjoying the spoils of government. -

United Nations Development Programme Uganda

United Nations Development Programme Uganda 2019 ANNUAL REPORT DELIVERING TOGETHER TO TRANSFORM UGANDA UNDP Uganda Annual Report 2019 Publisher: UNDP Uganda Published by the UNDP Communications Unit Photographs: UNDP Uganda 2019 Graphic Design: David Lloyd © 2020 United Nations Development Programme Plot 11, Yusuf Lule Road, Nakasero P.O.BOX 7184, Kampala, Uganda. Phone: +256417 112100/30 +256414 344801 Email: [email protected] Facebook: UNDPUganda Website: www.ug.undp.org Medium: @UNDPUganda Twitter: @UNDPUganda YouTube: UNDPinUganda About UNDP Uganda | i About UNDP Uganda The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is the leading United Nations organization committed to ending injustices of poverty, inequality and climate change globally. Working with our broad network of experts and partners in 170 countries, we help nations to build integrated, lasting solutions for the people and the planet. In Uganda, UNDP is committed to supporting the Government to achieve sustainable development outcomes, create opportunities for empowerment, protect the environment, minimize natural and man-made disasters, build strategic partnerships, and improve the quality of life for all citizens, as set out in the UNDP Uganda Annual Report 2019 UNDP Uganda’s Transformative Country Programme. The year Publisher: UNDP Uganda 2019 brought UNDP Uganda close to the end of the United Published by the UNDP Communications Unit Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) for the Photographs: UNDP Uganda 2019 period 2016-2020 and the transitioning to a new development Graphic Design: David Lloyd framework premised on partnerships and cooperation. © 2020 United Nations Development Programme UNDP also laid the foundation for the realisation of the Plot 11, Yusuf Lule Road, Nakasero 2020-2030 Decade of Action and is supporting the country to P.O.BOX 7184, Kampala, Uganda. -

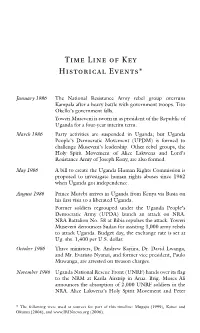

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

Making a Difference Beyond Numbers

Making A Difference 9 789 970 2 9 010123 9630 ISBN: 9970-29-013-0 Beyond Numbers: Towards women's substantive engagement in political leadership in Uganda i Research Team Prof. Josephine Ahikire; Lead Researcher Dr. Peace Musiimenta Mr. Amon Ashaba Mwiine Ms Ruth Ojiambo Ochieng Ms Juliet Were Oguttu Ms Helen Kezie-Nwoha Ms Suzan Nkinzi Mr. Bedha Balikudembe Kirevu Mr. Archie Luyimbazi Ms Harriet Nabukeera Musoke Ms Prossy Nakaye Ms Gloria Oguttu Adeti Editors Mr. Bedha Balikudembe Kirevu Ms Ruth Ojiambo Ochieng Ms Juliet Were Oguttu Ms Helen Kezie-Nwoha Correspondence: Please address all correspondence to: The Executive Director Isis-Women’s International Cross Cultural Exchange (Isis-WICCE) Plot 7 Martyrs Rd. Ntinda P.O.Box 4934 Kampala – Uganda Tel: 256-414-543953 Fax: 256-414-543954 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.isis.or.ug ISBN: 9970-29-013-0 All Rights Reserved. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate this publication for education and non commercial purposes should be addressed to Isis-WICCE. Design and Layout: WEVUGIRA James Ssemanobe ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of tables iv Acronyms v Acknowledgement vi Foreword viii Executive Summary x 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to the Study 1 1.2 Focus of the Study 3 1.3 Study Objectives 4 1.4 Methodology 5 1.5 Women Political Leaders Making a Difference: A Conceptual Mapping 6 2.0 The Numbers: An Overview 7 2.1 Parliament and District Local Councils 7 2.2 Women Political Leaders in Other Government Institutions 11 3.0 Women Political Leaders beyond Physical Presence -

“Repositioning Family Planning and Reproductive Health in the Eastern and Southern Africa Region: Challenges and Opportunities”

SEAPACOH Southern and East African Parliamentary Partners in Population and Development German Foundation for United Nations Population Fund Alliance of Committees of Health Africa Regional Office (PPD ARO) World Population (DSW) (UNFPA) Regional Meeting of Parliamentary Committees on Health in Eastern and Southern Africa: “Repositioning Family Planning and Reproductive Health in the Eastern and Southern Africa Region: Challenges and Opportunities” Munyonyo Commonwealth Resort, Kampala, Uganda 28-29 September 2010 Logistical Information for Delegates Welcome! The 2010 Regional Meeting of Parliamentary Committees on Health in Eastern and Southern Africa is at the Munyonyo Commonwealth Resort, Kampala, Uganda. Please refer to the programme for full details on the schedule of sessions. Meeting location MCWRL Banqueting Hall Munyonyo Commonwealth Resort P.O. Box 3673, Kampala, Uganda Tel: calling from outside Uganda= +256-41-771-6000 or +256-41-771-6200 calling from inside Uganda= 041-771-6000 or 041-771-6200 Fax: calling from outside Uganda= +256-41-771-6350 or +256-41-771-6351 calling from inside Uganda= 041-771-6350 or 041-771-6351 http://www.munyonyocommonwealth.com/ Registration Delegates will be required to register personally at the venue of the meeting, where they can pick up their badges and conference materials at 8:00 am on Tuesday, 28 September 2010. Useful phone numbers • Mr. Patrick Mugirwa, Programme Officer, PPD ARO from an out-of-country phone line: +256-772-776-775 from within Uganda: 0772-776-775 • Mr. Abdelylah Lakssir, International Programme Officer, PPD ARO from an out-of-country phone line: +256-772-779-714 from within Uganda: 0772-779-714 • Ms. -

2Bcf27309359df31492577190

APRIL 2010 HORN OF AFRICA BULLETIN ANALYSES • CONTEXT • CONNECTIONS Analyses ► Peacebuilding in Somalia – continued role of the grassroots communities ►Chaotic Somalia: options for lasting peace ► Somalia: twenty years after News and events Resources Peacebuilding in Somalia – continued role of the grassroots communities Beneath the apparent homogeneity at the national level, the Somali society remains divided, not only by social and occupational stratifications, differences between urban and rural sectors, but also by clan forms of social organization to which Somalis belong. Without getting into details of the conflict, the current situation is that the country is still going through a deep crisis with a socio-political and economic fabric completely destroyed by almost two decades of armed conflict. The internationaliza- tion of the conflict (e.g. piracy and perceived threats of terrorism) together with the multiple stakeholders interests are reasons behind the endless search for peace in this country. John Paul Lederach describes conversation which took ‘‘place between two Somali friends over how the house of peace should be built in their war-torn home- land’’. One argued that ‘‘the head needed to be established in order for the body to function. The other suggested that the foundation of the house had to be laid if the roof was to be held up’’ (Lederach, 37, 1999). He continues to argue that two opposite theories are derived from this conversation about how to ‘‘understand and approach the peace building within a population. Using a mixed metaphor from the same conversation, one argued that peace is built from the top down; the second sug- gested that it is constructed from the bottom up’’ “Constructing a peace process in deeply divided societies and situations of inter- nal armed conflict requires an operative frame of reference that takes into considera- tion the legitimacy, uniqueness, and interdependency of the needs and resources of BULLETIN A the grassroots, middle range, and top level”( Edwards, 8, 2008). -

Politics in Uganda Today

Politics in Uganda Today June 24, 2014 Structure of Government • National--Presidential Republic – President is head of state and government • Regions--Northern, Central, Eastern, Western • District--112 in the country (111+ Kampala) – Chairperson of the Local Council V – National gov’t appoints a Resident District Commissioner – May overlap with Kingdom government • County • Sub-county • Village(Parish)--local council I US Dept. of State Background Notes • Constitution: Ratified July 12, 1995 • Independence: October 9, 1962 • Branches: Executive--president, vice president, prime minister, cabinet • Legislative--parliament; since February 2011 375 members: 112 special seats for women, 10 special seats for military, five for youth, and five for persons with disabilities. • Judicial--Magistrates' Courts, High Court, Political Parties • 38 registered parties • Major parties include – National Resistance Movement (NRM, ruling party) – Forum for a Democratic Change (FDC) – Democratic Party (DP) – Conservative Party (CP) – Justice Forum (JEEMA) – Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) Principal Government Officials • President and Commander in Chief--Yoweri Kaguta Museveni • Vice President--Edward Ssekandi • Prime Minister--Amama Mbabazi • Foreign Minister--Sam Kutesa • Minister of Defense--Crispus Kiyonga • Ambassador to the United States--Perezi K. Kamunanwire • Ambassador to the United Nations--acting Article by Tangri & Mwenda • WHY is Museveni (like other African leaders) so determined to maintain power? • Museveni believes he is indispensable