An Analysis of Uganda's Truth Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Uganda Joint Statement

JOINT STATEMENT ON THE OCCASION OF THE VISIT TO UGANDA OF THE VICE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, Mr MOHAMMAD HAMID ANSARI FROM 21 – 23 FEBRUARY 2017 The Vice President of India, Mr Mohammad Hamid Ansari paid an official visit to Uganda from 21st to 23rd February 2017. The Vice President was accompanied by his spouse Mrs Salma Ansari and a delegation comprising Minister of State, Mr Vijay Sampla, four Members of Parliament, other Senior Government Officials and a business delegation. 2. Vice President Ansari met and held bilateral discussions with President of the Republic of Uganda Mr Yoweri Museveni, at State House, Entebbe on Wednesday 22nd February 2017. Vice President Ansari also met the Vice President of Uganda Mr Edward Ssekandi, Speaker of Uganda Ms Rebecca Alitwala Kadaga and Prime Minister Mr Ruhakana Rugunda. The Vice President addressed a business event jointly organised by the Private Sector Foundation of Uganda and Federation of India Chambers of Commerce and Industry. VP Ansari visited the Source of the Nile in Jinja and paid floral tribute at the bust of Mahatma Gandhi. VP also interacted with the Indian Community in Uganda. 3. During the discussions, Vice President Ansari and President Museveni acknowledged the long-standing excellent historical relations that exist between Uganda and India. Both sides acknowledged the huge potential in India-Uganda bilateral relations and re-affirmed the mutual desire to strengthen economic, diplomatic, military, technical, educational, scientific and cultural cooperation between India and Uganda. In this regard, it was acknowledged that there were an estimated over 26000 persons of Indian origin in Uganda who contribute immensely towards Uganda’s national economy. -

Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights Helen Liebling-Kalifani

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 4 Article 1 May-2007 Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights Helen Liebling-Kalifani Angela Marshall Ruth Ojiambo-Ochieng Nassozi Margaret Kakembo Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Liebling-Kalifani, Helen; Marshall, Angela; Ojiambo-Ochieng, Ruth; and Kakembo, Nassozi Margaret (2007). Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(4), 1-17. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss4/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2007 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Experiences of Women War-Torture Survivors in Uganda: Implications for Health and Human Rights By Helen Liebling-Kalifani,1 Angela Marshall,2 Ruth Ojiambo-Ochieng,3 and Nassozi Margaret Kakembo4 The effect of the aggressive rapes left me with constant chest, back and abdominal pain. I get some treatment but still, from time to time it starts all over again. It was terrible (Woman discussing the effects of civil war during a Kamuli Parish focus group). Amongst the issues treated as private matters that cannot be regulated by international norms, violence against women and women‟s health are particularly critical. -

MAY JUNE 2016 Pages.Indd

34 NEW VISION, Thursday, June 9, 2016 ADVERTISERS SUPPLEMENT OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER LUWERO TRIANGLE 2016 HEROES DAY SUPPLEMENT Bull fatt ening project for Kithoma II Youth group, Ntoroko District. Hon.Kataike Sarah Ndoboli, Mrs. Christi ne Guwatudde Kintu Hon. Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda Outgoing Minister of State for Permanent Secretary Prime Minister of the Republic Luwero Triangle H. E. Gen Yoweri Kaguta Museveni. of Uganda President of the Republic of Uganda The Ministry of Luwero Traingle, Congratulate The President of the A heifer given to Agaryawamu mens group in Kalagi Republic of Uganda His Excellency Gen. Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, and all Hereos Mulagi sub county Kyankwanzi district of Uganda as we mark 27th HEROES DAY ANNIVERSARY BACKGROUND Each block yard was supported with an M7 hydra form twin machine he portf olio of Luwero Triangle was started immediately aft er for producing interlocking blocks; a Vibra V3SE Conventi onal Block the Nati onal Resistance Movement Liberati on (NRM) struggle and paving machines; a Hydra form mobile Jaw Crushers for of 1981-1986. The primary responsibility of the programme crushing rocks and stones; a hydraform 300 litre mobile pan mixers T for mixing soil and cement mixture; and a hydra form rotary sieves was to ensure reconstructi on of the Luwero Triangle Districts and coordinate payment of war debts claims. for preparati ons of soil for block producti on. Each of the Block Yards will be provided with one Tipper Lorry to assist in the transportati on The portf olio currently coordinates three major programmes; of their mateti als and products. -

Museveni, Mbabazi, Barya Nominated

2 NEW VISION, Wednesday, November 4, 2015 ELECTION 2016 Mbabazi shaking hands with Kiggundu during nomination Baryamureeba hands documents to Kiggundu at Namboole Museveni, Mbabazi, Barya nominated By Moses Walubiri Baryamureeba nominated and Pascal Kwesiga At 10:55am, 17 minutes after making his entrance, Baryamureeba too got The faces of candidates to appear nominated. on the ballot paper for next year’s The academic-turned-politician presidential elections became clearer said he intends to revamp Uganda’s yesterday, following the nomination health and education sectors an of President Yoweri Museveni and integral component of his campaign. former premier, Amama Mbabazi. “You cannot think of development The other candidate nominated when you have an ailing health by the Electoral Commission (EC) sector, and broken education sector,” was former Makerere University Baryamureeba noted, saying Mbabazi vice-chancellor, Prof. Venansius and Museveni are the same. Baryamureeba. “If Mbabazi and Museveni were Although the EC expected five of bishops, they would be retired clerics the 10 candidates that had satisfied now. I am just 46 years. This country the requirement of collecting needs someone of my energy and signatures of not less than 100 calibre,” he added. voters in at least two thirds of all the Mbabazi and Baryamureeba districts in Uganda, only four turned picked the signs of a chair and a up. clock respectively which they will “By the powers entrusted in me use during their campaigns since by the Electoral Commissions Act, they are contesting as independent I declare Yoweri Kaguta Museveni candidates. a duly nominated candidate,” EC However, Charles Bbale Lwanga of chairman, Dr. -

REALITY CHECK Multiparty Politics in Uganda Assoc

REALITY CHECK Multiparty Politics in Uganda Assoc. Prof. Yasin Olum (PhD) The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung but rather those of the author. MULTIPARTY POLITICS IN UGANDA i REALITY CHECK Multiparty Politics in Uganda Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 51A, Prince Charles Drive, Kololo P. O. Box 647, Kampala Tel. +256 414 25 46 11 www.kas.de ISBN: 978 - 9970 - 153 - 09 - 1 Author Assoc. Prof. Yasin Olum (PhD) © Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be produced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung ii MULTIPARTY POLITICS IN UGANDA Table of Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................... 1 List of Tables ................................................................................................. 3 Acronyms/Abbreviations ................................................................................. 4 Introduction .................................................................................................. 7 PART 1: THE MULTIPARTY ENVIRONMENT: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND, LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND INSTITUTIONS ........................... 11 Chapter One: ‘Democratic’ Transition in Africa and the Case of Uganda ........................... 12 Introduction ................................................................................................... 12 Defining Democracy -

Uganda Relations

India-Uganda Relations The bilateral relations between India and Uganda are characterised by historical cultural linkages, extensive economic and trade interests, and a convergence on major bilateral and international issues. A 27000+ Indian/PIO population in Uganda, a bilateral trade of nearly US$ 1.3 billion, a steady surge of Indian investments making India consistently one of the top investors in Uganda, capacity building training programmes and institutions, and a common and deep respect for universal values like democracy and peace reinforce the architecture of India-Uganda bilateral relations. Trade and economic interests brought several Indians to the shores of East Africa as early as the 17th century in dhows laden with their wares. Eventually a number of Indians settled in East Africa, and many made Uganda their home. India's freedom struggle inspired the early Ugandan activists to fight colonization and Uganda eventually achieved Independence in 1962. India established it diplomatic presence in Uganda in 1965. Except for the era of Idi Amin’s reign in early 70's when nearly 55,000 Persons of Indian Origin (PIOs) and 5000 Indian nationals were expelled and their properties confiscated, relations between the two countries have since been cordial. The anti-Indian policies of Amin were reversed when the current President YoweriKagutaMuseveni came to power in 1986. The current Government’s progressive policies ensured that the India-Uganda relations were restored to erstwhile levels. Uganda remains an important partner in Africa. India and Uganda closely cooperate at regional and international fora. Exchange of High-Level Visits: From India: • Prime Minister Shri. -

The Anguish of Northern Uganda

THE ANGUISH OF NORTHERN UGANDA RESULTS OF A FIELD-BASED ASSESSMENT OF THE CIVIL CONFLICTS IN NORTHERN UGANDA Robert Gersony Submitted to: United States Embassy, Kampala USAID Mission, Kampala August 1997 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Maps and Charts Map of Uganda Map of Northern Uganda Ethnic Map of Uganda Chart A Five Phases of Insurgency - Gulu/Kitgum 18 Chart B Selective Timeline 19 INTRODUCTION 1 Assessment procedures 2 Limitations 4 Appreciation 4 Organization of report 5 SECTION I THE CONFLICT IN GULU AND KITGUM 6 Background 6 Amin’s persecution of Acholis 7 Luwero: the ghost that haunts Acholi 8 General Tito Okello Lutwa’s Government 11 Advent of the NRA 12 Acholi attitudes/Contributing causes of the war 14 Was poverty a cause of the war? 17 War in Acholi as an extension of the Luwero conflict 17 Five phases of war in Acholi 20 Phase I Uganda People’s Democratic Army 20 The FEDEMU factor 21 UPDA popular support/NRA brutal response 23 Phase II Alice Auma Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement 24 Alice’s military campaign 25 Why did the Acholi people follow Alice? 26 June 1988 NRA/UPDA peace accords 26 The cattle factor 27 Phase III Severino Likoya Kiberu - “God the Father” 29 Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army 30 Phase IV Joseph Kony’s earlier period 31 Evolution in human rights conduct 33 Government of Uganda peace initiative 33 Phase V Joseph Kony’s LRA - current period 35 NRA/UPDF effectiveness 36 Human rights conduct of the parties - 1994 to the present 38 LRA human rights conduct 38 LRA signal incidents 38 Atiak massacre 38 Karuma/Pakwach convoy ambush 39 Acholpi refugee camp massacre 40 St. -

Africa Confidential

www.africa-confidential.com 4 April 2003 Vol 44 No 7 AFRICA CONFIDENTIAL UGANDA/RWANDA 2 UGANDA Soccer war, Congo war In the phoney war, the score was The great U-turn nil-nil as Rwanda and Uganda President Museveni calls for the freeing of parties and the chance of played a qualifier in Africa’s Cup of a third term at the top Nations soccer tournament last It was the sharpest of U-turns. President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, who has vehemently defended his weekend in Kigali. In the real war in eastern Congo-Kinshasa, ‘no-party system’ of government since he won power in 1986, now wants to lift the ban on multi-party Kampala and Kigali back rival politics. He told delegates at an apprehensive congress of the ruling National Resistance Movement at militias and may be preparing for Kyankwanzi, north of Kampala, on 26 March, that they should accommodate those politicians who had another direct confrontation over persuaded ‘about 20 per cent’ of Ugandans to vote against his no-party system. The NRM would remain Congo’s mineral riches. unchanged, a broad church: ‘Those who want to experiment again with political parties can do so alongside the Movement, which should maintain its present identity’. So the no-party system (with its KENYA 3massive state subventions) is to compete with others in the presidential election due in 2006. The change of heart is more pragmatic than ideological. The NRM’s middle ranks are increasingly Victory is not enough calling for political liberalisation and modernisation. They also want more power within the Movement Two interlinked questions gnaw at over its ruling clique, who have been conspicuously enjoying the spoils of government. -

United Nations Development Programme Uganda

United Nations Development Programme Uganda 2019 ANNUAL REPORT DELIVERING TOGETHER TO TRANSFORM UGANDA UNDP Uganda Annual Report 2019 Publisher: UNDP Uganda Published by the UNDP Communications Unit Photographs: UNDP Uganda 2019 Graphic Design: David Lloyd © 2020 United Nations Development Programme Plot 11, Yusuf Lule Road, Nakasero P.O.BOX 7184, Kampala, Uganda. Phone: +256417 112100/30 +256414 344801 Email: [email protected] Facebook: UNDPUganda Website: www.ug.undp.org Medium: @UNDPUganda Twitter: @UNDPUganda YouTube: UNDPinUganda About UNDP Uganda | i About UNDP Uganda The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is the leading United Nations organization committed to ending injustices of poverty, inequality and climate change globally. Working with our broad network of experts and partners in 170 countries, we help nations to build integrated, lasting solutions for the people and the planet. In Uganda, UNDP is committed to supporting the Government to achieve sustainable development outcomes, create opportunities for empowerment, protect the environment, minimize natural and man-made disasters, build strategic partnerships, and improve the quality of life for all citizens, as set out in the UNDP Uganda Annual Report 2019 UNDP Uganda’s Transformative Country Programme. The year Publisher: UNDP Uganda 2019 brought UNDP Uganda close to the end of the United Published by the UNDP Communications Unit Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF) for the Photographs: UNDP Uganda 2019 period 2016-2020 and the transitioning to a new development Graphic Design: David Lloyd framework premised on partnerships and cooperation. © 2020 United Nations Development Programme UNDP also laid the foundation for the realisation of the Plot 11, Yusuf Lule Road, Nakasero 2020-2030 Decade of Action and is supporting the country to P.O.BOX 7184, Kampala, Uganda. -

Kony, Conflict, and the Cultural Impacts in Northern Uganda By

A Lost Generation? Kony, Conflict, and the Cultural Impacts in Northern Uganda by David W. Westfall M.A., Kansas State University, 2009 An Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Social Work College of Arts and Sciences Kansas State University Manhattan, Kansas 2017 Abstract For over two decades the people of northern Uganda endured horrific atrocities during Africa’s forgotten war in the form of attacks and child abductions by the Lord’s Resistance Army, animal rustling by neighboring ethnic groups, and internal displacement of an unimaginable 90 percent of the northern parts of the country. With the majority of internally displaced persons spending over a decade in IDP camps, an entire generation of Acholi was socialized and acculturated in a non-traditional environment. A decade after the last LRA attack, I ask, what are the cultural impacts of the conflict and how has the culture recovered from the trauma. Using ethnographic analysis, this dissertation is rooted in over 150 interviews. While it has been presented to the world at large that Joseph Kony’s LRA is the one of the biggest problems facing the region, I found it is not the case. Interviewees discussed serious inadequacies in education, land conflict, culture loss, climate change, drought, famine, a perceived generational divide, and a strong distrust of the Ugandan government. Additionally this research examines the case of Uganda through the lens of, and attempts to build upon, Jeffrey Alexander’s cultural trauma process. I argue the increasing reach and instantaneous nature of social media can interact with, alter, and prolong the trauma process. -

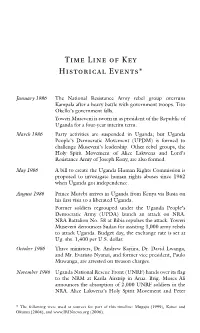

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006).