Walking with Giants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For Preview Only

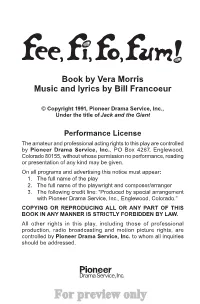

Book by Vera Morris Music and lyrics by Bill Francoeur © Copyright 1991, Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Under the title of Jack and the Giant Performance License The amateur and professional acting rights to this play are controlled by Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., PO Box 4267, Englewood, Colorado 80155, without whose permission no performance, reading or presentation of any kind may be given. On all programs and advertising this notice must appear: 1. The full name of the play 2. The full name of the playwright and composer/arranger 3. The following credit line: “Produced by special arrangement with Pioneer Drama Service, Inc., Englewood, Colorado.” COPYING OR REPRODUCING ALL OR ANY PART OF THIS BOOK IN ANY MANNER IS STRICTLY FORBIDDEN BY LAW. All other rights in this play, including those of professional production, radio broadcasting and motion picture rights, are controlled by Pioneer Drama Service, Inc. to whom all inquiries should be addressed. For preview only FEE, FI, FO, FUM! Adapted and dramatized from the Benjamin Tabart version of the English folktale, “The History of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean” Book by VERA MORRIS Music and Lyrics by BILL FRANCOEUR CAST OF CHARACTERS (In Order Of Appearance) # of lines JACK ................................................brave young lad; loves 149 adventure SUSAN .............................................his sister 53 JACK’S MOTHER .............................about to lose her farm 65 VILLAGE WOMAN #1 ......................lives in fear of the Giant 11 VILLAGE WOMAN #2 ......................more -

The Titanic Origin of Humans: the Melian Nymphs and Zagreus Velvet Yates

The Titanic Origin of Humans: The Melian Nymphs and Zagreus Velvet Yates HE FIRST PART of this paper examines a minor mystery in Hesiod’s Theogony, centering around the Melian Nymphs, Tin order to assess the suggestions, both ancient and modern, that the Melian Nymphs were the mothers of the human race. The second part examines the afterlife of Hesiod’s Melian Nymphs over a thousand years later, in the allegorizing myths of late Neoplatonism, in order to suggest that the Hesiodic myth in which the Melian Nymphs primarily figure, namely the castration of Ouranos, has close similarities to a central Neoplatonic myth, that of Zagreus. Both myths depict a “Titanic” act of destruction and separation which leads to the birth of the human race. Both myths furthermore seek to account for a divine element which human nature retains from its origins. The Melian Nymphs in Hesiod ˜ssai går =ayãmiggew ép°ssuyen aflmatÒessai, pãsaw d°jato Ga›a: periplom°nou d' §niautoË ge¤nat' ÉErinËw te krateråw megãlouw te G¤gantaw, teÊxesi lampom°nouw, dol¤x' ¶gxea xers‹n ¶xontaw, NÊmfaw y' ìw Mel¤aw kal°ous' §p' épe¤rona ga›an. Gaia took in all the bloody drops that spattered off, and as the seasons of the year turned round she bore the potent Furies and the Giants, immense, dazzling in their armor, holding long spears in their hands, and then she bore the Melian Nymphs on the boundless earth.1 1 Theog. 183–187. Translations of Hesiod adapted from A. Athanassakis, Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Shield (Baltimore 1983). -

Giant Hogweed Please Destroy Previous Editions

MSU Extension Bulletin E-2935 June 2012 Giant Hogweed Please destroy previous editions An attractive but dangerous federal noxious weed. Have you seen this plant in Michigan? Hogweed is hazardous Wash immediately with soap and water if skin exposure occurs. If pos- Giant hogweed is a majestic plant sible, keep the contacted area cov- that can grow over 15 feet. Although ered with clothing for several days to attractive, giant hogweed is a public reduce light exposure. Giant hogweed health hazard because it can cause se- (Heracleum mantegazzianum) is a vere skin irritation in susceptible people. federal noxious weed, so it is unlaw- The plant exudes a clear, watery sap that ful to propagate, sell or transport this causes photodermatitis, a severe skin plant in the United States. The U.S. reaction. Skin contact followed by ex- Department of Agriculture (USDA) posure to sunlight may result in painful, has been surveying for this weed since burning blisters and red blotches that 1998 and several infestations have later develop into purplish or blackened been identified in Michigan. For more USDA APHIS PPQ Archive, USDA APHIS PPQ, Bugwood.org Archive, USDA APHIS PPQ USDA scars. The reaction can happen within information about giant hogweed, visit It’s a tall majestic plant, 24 to 48 hours after contact with sap, the Michigan Department of Agricul- and scars may persist for several years. ture and Rural Development at www. but DON’T TOUCH IT! Contact with the eyes can lead to tempo- michigan.gov/exoticpests. rary or permanent blindness. Use common sense around giant hogweed Don’t touch or handle plants using Don’t transplant or give away your bare hands. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

Management Plan for the Giant Land Crab (Cardisoma Guanhumi) in Bermuda

Management Plan for the Giant Land Crab (Cardisoma guanhumi) in Bermuda Government of Bermuda Ministry of Home Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources 1 Management Plan for the Giant Land Crab (Cardisoma guanhumi) in Bermuda Prepared in Accordance with the Bermuda Protected Species Act 2003 This management plan was prepared by: Alison Copeland M.Sc., Biodiversity Officer Department of Environment and Natural Resources Ecology Section 17 North Shore Road, Hamilton FL04 Bermuda Contact email: [email protected] Published by Government of Bermuda Ministry of Home Affairs Department of Environment and Natural Resources 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 3 LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ 4 LIST OF TABLES .............................................................................................................. 4 DISCLAIMER .................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 7 PART I: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 9 A. Brief Overview .......................................................................................................... -

KOERNER S HAVES by BUFFALO N Vv

; KOERNER S HAVES BY BUFFALO N Vv ! = \A #1 t : 4 ¢ Jack the Giant=Killer. The Giant Stepped on Jack’s Trap and Fell Headlong into the Pit. [° the days of the renowned King Arthur there lived a Cornishman named Jack, who was famous for his valiant deeds. His bold and warlike spirit showed itself in his boyish days; for Jack took especial delight in listening to the wonderful tales of giants and fairies, and of the extraordinary feats of valor displayed by the knights of King Arthur’s Round Table, which his father would sometimes relate. Jack’s spirit was so fired by these strange accounts, that he determined, if ever he became a man, that he would destroy some of the cruel giants who infested the land. Not many miles from his father’s house there lived, on the top of St. Michael’s Mount, a huge giant, who was the terror of the country round, who was named Cormoran, from his voracious appetite. It is said that he was eighteen feet in height. When he required food, he came down from his castle, and, seizing on the flocks of the poor people, would throw half a dozen oxen over his shoulders, and suspend as many sheep as he could carry, and stalk back to his castle. He had carried on these depredations many years ; and the poor Cornish people were well-nigh ruined. Jack went by night to the foot of the mount and dug a very deep pit, which he covered with sticks and straw, and over which he strewed the earth. -

Greek Mythology

Greek Mythology The Creation Myth “First Chaos came into being, next wide bosomed Gaea(Earth), Tartarus and Eros (Love). From Chaos came forth Erebus and black Night. Of Night were born Aether and Day (whom she brought forth after intercourse with Erebus), and Doom, Fate, Death, sleep, Dreams; also, though she lay with none, the Hesperides and Blame and Woe and the Fates, and Nemesis to afflict mortal men, and Deceit, Friendship, Age and Strife, which also had gloomy offspring.”[11] “And Earth first bore starry Heaven (Uranus), equal to herself to cover her on every side and to be an ever-sure abiding place for the blessed gods. And earth brought forth, without intercourse of love, the Hills, haunts of the Nymphs and the fruitless sea with his raging swell.”[11] Heaven “gazing down fondly at her (Earth) from the mountains he showered fertile rain upon her secret clefts, and she bore grass flowers, and trees, with the beasts and birds proper to each. This same rain made the rivers flow and filled the hollow places with the water, so that lakes and seas came into being.”[12] The Titans and the Giants “Her (Earth) first children (with heaven) of Semi-human form were the hundred-handed giants Briareus, Gyges, and Cottus. Next appeared the three wild, one-eyed Cyclopes, builders of gigantic walls and master-smiths…..Their names were Brontes, Steropes, and Arges.”[12] Next came the “Titans: Oceanus, Hypenon, Iapetus, Themis, Memory (Mnemosyne), Phoebe also Tethys, and Cronus the wily—youngest and most terrible of her children.”[11] “Cronus hated his lusty sire Heaven (Uranus). -

Greek Myths Student Sample

CONTENTS Why Study Greek Mythology? ......................................................................................................................................5 How to Use This Guide ...................................................................................................................................................6 Lesson 1: Olden Times, Gaea, The Titans, Cronus (pp. 9-15) ....................................................................................8 Lesson 2: Zeus and his Family (pp. 16-21) .................................................................................................................10 Lesson 3: Twelve Golden Thrones (pp. 22-23) ...........................................................................................................12 Lesson 4: Hera, Hephaestus (pp. 24-29) .....................................................................................................................14 Lesson 5: Aphrodite, Ares, Athena (pp. 30-37) ..........................................................................................................16 Review Lesson: Lessons 1-5 ........................................................................................................................................18 Lesson 6: Poseidon, Apollo (pp. 38-43) .......................................................................................................................26 Lesson 7: Artemis, Hermes (pp. 44-55) .......................................................................................................................28 -

Giants: Legends & Lore of Goliaths

PERHAPS MYTHOLOGY CONTAINS MORE TRUTH THAN WE REALIZE! The word “myth” has come to mean “fiction” in our minds, and so some people take Bible accounts, Aesop’s fables, and Greek myths and place them all in the same category. But what if some of the old legends are true? Rather than dismiss these narratives, perhaps we should investigate them. In this case, the world is filled with giant legends that speak of heroes and wars. In this highly engaging book of giants you will discover ? Unique glimpses into the ancient accounts of giants from around the world @ What does the Bible say about giants? ? Full-color artistry developed in an interactive format with fold outs and flaps, booklets, and more! @ A spectacular center spread stretching 4-feet across! It is fascinating that the ancient world agreed on many aspects of the Martin Bible, one of these being that early in the history of mankind, a race of violent, yet intelligent giants walked the earth, were destroyed by the Flood. Through historical records, the pre-Flood and post-Flood worlds are reconstructed, with giants re-emerging in and around Israel, and you’ll see one more reason that the Bible can be trusted. RELIGION/Biblical Studies/General JUVENILE NONFICTION/Religious/ Christian/General $18.99 U.S. ISBN-13: 978-0-89051-864-9 EAN First printing: June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Master Books. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used Odysseus Blinds Polyphemus or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in articles and reviews. -

Volume One: Arthur and the History of Jack and the Giants

The Arthuriad – Volume One CONTENTS ARTICLE 1 Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer DOCUMENTS 5 The History of Jack and the Giants (1787) 19 The 1711 Text of The History of Jack and the Giants 27 Jack the Giant Killer: a c. 1820 Penny Book 32 Some Arthurian Giant-Killings Jack & Arthur: An Introduction to Jack the Giant-Killer Caitlin R. Green The tale of Jack the Giant-Killer is one that has held considerable fascination for English readers. The combination of gruesome violence, fantastic heroism and low cunning that the dispatch of each giant involves gained the tale numerous fans in the eighteenth century, including Dr Johnson and Henry Fielding.1 It did, indeed, inspire both a farce2 and a ‘musical entertainment’3 in the middle of that century. However, despite this popularity the actual genesis of Jack and his tale remains somewhat obscure. The present collection of source materials is provided as an accompaniment to my own study of the origins of The History of Jack and the Giants and its place within the wider Arthurian legend, published as ‘Tom Thumb and Jack the Giant-Killer: Two Arthurian Fairy Tales?’, Folklore, 118.2 (2007), pp. 123-40. The curious thing about Jack is that – in contrast to that other fairy-tale contemporary of King Arthur’s, Tom Thumb – there is no trace of him to be found before the early eighteenth century. The first reference to him comes in 1708 and the earliest known (now lost) chapbook to have told of his deeds was dated 1711.4 He does not appear in Thackeray’s catalogue of chapbooks -

Major Themes and Motifs in the Dionysiaca

chapter 6 Major Themes and Motifs in the Dionysiaca Fotini Hadjittofi A feature which will immediately strike the first-time reader of Nonnus’ Dionysiaca is the poet’s penchant for creating formulaic scenes or expressions: verses can be repeated verbatim or in a slightly varied form, and passages can be recast several times, with different protagonists and only minor alterations.1 These recurrent scenes and expressions are certainly a manifestation of Nonnus’ aesthetic principle of ποικιλία (variatio),2 and have an obvious role to play in structuring the poem. For example, in looking for unifying threads that would tie together the disparate episodes of the Dionysiaca, scholars have identified a set of close structural parallels between the first and last books of the epic.3 Thus, the narrative proper begins with a rape (of Europa, by Zeus) and ends with a rape (of Aura, by Dionysus). The Typhonomachy, in which Zeus defeats Typhoeus, in Books 1–2 corresponds to the Gigantomachy, in which Dionysus defeats the Giants of Thrace, in Book 48. The tragic narratives of Actaeon (Book 5) and Pentheus (Books 44–46) clearly echo each other. Even though this chapter will often focus on the thematic correspondences between the first and last books (as themes which appear in these narratively privileged positions are likely to be fundamental for the whole poem), it does not aim to explore structural questions, such as how far we can push these particular similarities and to what extent Nonnus was indeed striving for a perfect ring composition.4 My aim is to provide an outline of the most important themes and motifs which recur throughout the entire epic, and which will be studied 1 The formularity of Nonnus’ language will not concern me in this chapter, but see D’Ippolito in this volume.