Timon of Athens. Edited by K. Deighton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timon of Athens: the Iconography of False Friendship

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU English Faculty Publications English Summer 1980 Timon of Athens: The Iconography of False Friendship Clifford Davidson Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/english_pubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Davidson, Clifford, "Timon of Athens: The Iconography of False Friendship" (1980). English Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/english_pubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. Timonof Athens. The Iconographyof False Friendship By CLIFFORD DAVIDSON THE REALIZATION THAT iconographic tableaux appear at central points in the drama of Shakespeare no longer seems to involve a radical critical perspective. Thus a recent study is able to show convincingly that the playwright presented audiences with a Hamlet who upon his first appear- ance on stage illustrated what the Renaissance would certainly have recognized as the melancholic contemplative personality.' As I have noted in a previous article, the hero of Macbeth when he sees the bloody dagger before him is in fact perceiving the image which most clearly denotes tragedy itself; in the emblem books, the dagger is indeed the symbol of tragedy,2 which will be Macbeth's fate if he pursues his bloody course of action. Such tableaux, it must be admitted, are often central to the meaning and the action of the plays. -

Discourses of Femininity in Thomas Shadwell's Adaptation of Timon Of

Outskirts Vol. 38, 2018, 1-17 “What gay, vain, pratting thing is this”: Discourses of femininity in Thomas Shadwell’s adaptation of Timon of Athens Melissa Merchant During the Restoration era (1660 to 1700), the plays of Shakespeare were routinely adapted in order to make them fit for the new stages and society in which they were being produced. Representations ‘femininity’ and ‘woman’ were re-negotiated following a tumultuous period in English history and the evidence of this can be seen in the Shakespearean adaptations. Theatrical depictions of women within the plays produced during this time drew on everyday discourses of femininity and were influenced by the new presence of professional actresses on the London stages. In a time before widespread literacy and access to multiple media platforms, the theatre served a didactic function as a site which could present “useful and instructive representations of human life" (as ordered by Charles II in his Letters Patent to the theatre companies in 1662). This paper argues that, on the stage, Restoration women were afforded three roles: gay, ideal or fallen. Each of these are evident within Thomas Shadwell’s adaptation of Timon of Athens. Introduction “Women are of two sorts,” claimed Bishop Aylmer during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, some were “wiser, better learned, discreeter, and more constant than a number of men” and the other “worse sort of them” were: Fond, foolish, wanton, flibbergibs, tattlers, triflers, wavering, witless, without council, feeble, careless, rash, proud, dainty, tale-bearers, eavesdroppers, rumour-raisers, evil-tongued, worse-minded, and in every way doltified with the dregs of the devil’s dunghill (Stretton 2005, 52). -

Olivia's Household John W. Draper PMLA, Vol. 49, No. 3. (Sep., 1934)

Olivia's Household John W. Draper PMLA, Vol. 49, No. 3. (Sep., 1934), pp. 797-806. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0030-8129%28193409%2949%3A3%3C797%3AOH%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z PMLA is currently published by Modern Language Association. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mla.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Feb 9 20:31:37 2008 XLIII OLIVIA'S HOUSEHOLD P Shakespeare's plays, as is generally admitted, are incomparably I greater than their sources, their greatness must inhere mainly in his changes and additions. -

Article (Published Version)

Article 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon ERNE, Lukas Christian Reference ERNE, Lukas Christian. 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon. Modern Philology, 2010, vol. 107, no. 3, p. 493-505 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14484 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 492 MODERN PHILOLOGY absorbs and reinterprets a vast array of Renaissance cultural systems. "Our other Shakespeare": Thomas Middleton What is outside and what is inside, the corporeal world and the mental and the Canon one, are "similar"; they are vivified and governed by the divine spirit in Walker's that emanates from the Sun, "the body of the anima mundi" LUKAS ERNE correct interpretation. 51 Campanella's philosopher has a sacred role, in that by fathoming the mysterious dynamics of the real through scien- University of Geneva tific research, he performs a religious ritual that celebrates God's infi- nite wisdom. To T. S. Eliot, Middleton was the author of "six or seven great plays." 1 It turns out that he is more than that. The dramatic canon as defined by the Oxford Middleton—under the general editorship of Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino, leading a team of seventy-five contributors—con- sists of eighteen sole-authored plays, ten extant collaborative plays, and two adaptations of plays written by someone else. The thirty plays, writ ten for at least seven different companies, cover the full generic range of early modern drama: eight tragedies, fourteen comedies, two English history plays, and six tragicomedies. These figures invite comparison with Shakespeare: ten tragedies, thirteen comedies, ten or (if we count Edward III) eleven histories, and five tragicomedies or romances (if we add Pericles and < Two Noble Kinsmen to those in the First Folio). -

Shakespeare Seminar

Shakespeare Seminar Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft Ausgabe 8 (2010) Shakespeare and the City: The Negotiation of Urban Spaces in Shakespeare’s Plays www.shakespeare-gesellschaft.de/publikationen/seminar/ausgabe2010 Shakespeare Seminar 8 (2010) EDITORS The Shakespeare Seminar is published under the auspices of the Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, Weimar, and edited by: Dr Christina Wald, Universität Augsburg, Fachbereich Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Universitätsstr. 10, D-86159 Augsburg ([email protected]) Dr Felix Sprang, Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Von-Melle-Park 6, D-20146 Hamburg ([email protected]) PUBLICATIONS FREQUENCY Shakespeare Seminar Online is a free annual online journal. It documents papers presented at the Academic Seminar panel of the spring conferences of the Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft. It is intended as a publication platform especially for the younger generation of scholars. You can find the current call for papers on our website. INTERNATIONAL STANDARD SERIAL NUMBER ISSN 1612-8362 © Copyright 2010 Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft e.V. CONTENTS Introduction by Christina Wald and Felix Sprang ............................................................................... 2 Timon’s Athens and the Wilderness of Philosophy by Galena Hashhozheva ................................................................................................. 3 Shakespeare at the Fringe: Playing the Metropolis by Yvonne Zips ............................................................................................................. -

Editorial Treatment of the Shakespeare Apocrypha

Egan, Gabriel. 2004j. 'Editorial Treatment of the Shakespeare Apocrypha, 1664-1737': A Paper Delivered at the Conference 'Leviathan to Licensing Act (The Long Restoration, 1650-1737): Theatre, Print and Their Contexts' at Loughborough University, 15-16 September Editorial treatment of the Shakespeare apocrypha, 1664-1737 by Gabriel Egan The third edition (F3) of the collected plays of Shakespeare appeared in 1663, and to its second issue the following year was added a particularly disreputable group of plays comprised Pericles, The London Prodigal, Sir John Oldcastle, A Yorkshire Tragedy, Thomas Lord Cromwell, The Puritan, and Locrine. Of these, only Pericles remains in the accepted Shakespeare canon, the edges of which are imprecisely defined. (At the moment it is unclear whether Edward 3 is in or out.) The landmark event for defining the Shakespeare canon was the publication of the 1623 First Folio (F1), with which, as Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor put it, "the substantive history of Shakespeare's dramatic texts virtually comes to an end" (Wells et al. 1987, 52). Only one more genuine Shakespeare play was first printed after 1623: The Two Noble Kinsmen, which appeared in a quarto of 1634 whose title-page attributed it to Shakespeare and Fletcher, "Gent[lemen]" (Fletcher & Shakespeare 1634, A1r). Perhaps inclusion in F1 should not be an important criterion for us and we should put more weight on such facts as Pericles's appearing in quarto in 1609 with a titlepage that claimed it was by William Shakespeare. But the same can be said for other plays that got added to the Folio in 1663: The London Prodigal, Sir John Oldcastle, and A Yorkshire Tragedy were printed in early quartos that named their author as William Shakespeare and the other three in quartos that named "W.S". -

Timon of Athens by William Shakespeare Produced by the College of the Holy Cross 2002-2003 Season Directed by Edward Isser

Timon of Athens By William Shakespeare Produced by The College of the Holy Cross 2002-2003 Season Directed by Edward Isser A Glorious Mess Ben Jonson, in his famed introductory note to the First Folio, wrote, “I remember, the players have often mentioned it as an honour to Shakespeare that in his writing (whatsoever he penned) he never blotted out line.” A close look at the text of Timon of Athens, however, challenges the notion that Shakespeare’s plays sprang from his consciousness fully composed requiring little or no revision. Timon of Athens, put simply, is a glorious mess. It contains numerous errors, problems, and performative challenges; character names change, certain scenes appear to be little more than outlines, the verse is often jarring and filled with overlong lines, and the text shifts abruptly from prose to verse without apparent reason. Moreover, there is no evidence that the play was ever performed during Shakespeare’s lifetime. A number of critics, reacting to the rough and unfinished quality of the text, have even conjectured that Shakespeare was working on it at the time of his death in 1616 and Thomas Middleton completed the unfinished work. Other critics, denying collaboration, assert the play was composed at some point in1605-6 because of its textual and thematic correspondence to King Lear. The debate over composition and dating will probably never be fully resolved. The Folio text of 1623 was apparently based upon a set of so- called “foul papers,” a preliminary draft submitted to the playhouse by the author prior to production. The problematic nature of the text and the harshness of the story have caused Timon to be generally ignored by scholars, teachers and directors. -

Notes on Timon of Athens: Origins, Analyses and Academic Notes of Same / Sdmace 2013

Notes on Timon of Athens: Origins, Analyses and academic notes of same / sdmace 2013 NOTES TAKEN FROM VARIOUS SOURCES Timon of Athens is a play by William Shakespeare about the fortunes of an Athenian named Timon (and probably influenced by the philosopher of the same name, as well), generally regarded as one of his most obscure and difficult works until recently. Originally grouped with the tragedies, it is generally considered such, but some scholars group it with the problem plays. “Timon of Athens” is believed to have first been performed between 1607 and 1608, whereas the text is believed to have first been printed in 1623 as a part of the First Folio. ORIGIN: Timon of Athens may refer to a historical figure who lived during the era of the Peloponnesian War. Or, more likely, to Timon of Phlius (c. 320 BC – c. 230 BC) who was a Greek skeptic philosopher, a pupil of Pyrrho, and a celebrated writer of satirical poems called Silloi. He was born in Phlius, moved to Megara, and then he returned home and married. He next went to Elis with his wife, and heard Pyrrho, whose tenets he adopted. He also lived on the Hellespont, and taught at Chalcedon, before moving to Athens, where he lived until his death. His writings were said to have been very numerous. He composed poetry, tragedies, satiric dramas, and comedies, of which very little remains. His most famous composition was his Silloi, a satirical account of famous philosophers, living and dead, in hexameter verse. The Silloi has not survived intact, but it is mentioned and quoted by several ancient authors. -

Thomas North's Writings in the Shakespeare Canon

Thomas North’s Writings in the Shakespeare Canon: An Introduction by Dennis McCarthy Thomas North’s Writings in the Shakespeare Canon—2 Table of Contents Introduction: Thomas North and Shakespeare’s Use of Old Plays Part I: 200 Northern Speeches and Lines Appearing in the Shakespeare Canon. Chapter 1: 20 Examples of Shakespeare Borrowings from North. This chapter describes the sources for 20 Shakespearean passages. All were first written by Thomas North, and nearly all are revealed here for the first time. In every case, North’s source passage does not appear in a chapter that is also furnishing a plot or subplot for one of the plays. For example, it does not derive from the chapters in North’s Plutarch’s Lives that inspired Shakespeare’s Roman tragedies. So there is no reason for the playwright to have had North’s text open in front of him. Rather, it is clear that, in nearly every case, the situation in the play reminded the dramatist of an earlier passage by North, which he would then reuse or paraphrase. It would seem almost like Shakespeare could recall every chapter of everything North ever wrote. In reality, Shakespeare was simply adapting North’s plays, and it was North who was recalling his prior passages and reusing them in these dramas. The last two examples, involving Julius Caesar and Coriolanus, indicate that the playwright would even intertwine passages from multiple translations of North. For example, even while he closely follows North’s Plutarch’s Lives, the dramatist still augments the Plutarchan passages with material from North’s The Dial of Princes and The Moral Philosophy of Doni. -

1607 the LIFE of TIMON of ATHENS William Shakespeare

1607 THE LIFE OF TIMON OF ATHENS William Shakespeare Shakespeare, William (1564-1616) - English dramatist and poet widely regarded as the greatest and most influential writer in all of world literature. The richness of Shakespeare’s genius transcends time; his keen observation and psychological insight are, to this day, without rival. Timon of Athens (1607) - A tragedy in which Timon loses his wealth and finds that he has lost his friends as well.He leaves Athens to live in a cave where he finds a treasure and meets the banished general, Alcibiades. DRAMATIS PERSONAE TIMON of Athens LUCIUS LUCULLUS SEMPRONIUS flattering lords VENTIDIUS, one of Timon’s false friends ALCIBIADES, an Athenian captain APEMANTUS, a churlish philosopher FLAVIUS, steward to Timon FLAMINIUS LUCILIUS SERVILIUS Timon’s servants CAPHIS PHILOTUS TITUS HORTENSIUS servants to Timon’s creditors POET PAINTER JEWELLER MERCHANT MERCER AN OLD ATHENIAN THREE STRANGERS A PAGE A FOOL PHRYNIA TIMANDRA mistresses to Alcibiades CUPID AMAZONS in the Masque Lords, Senators, Officers, Soldiers, Servants, Thieves, and Attendants SCENE: Athens and the neighbouring woods ACT I SCENE I. Athens. TIMON’S house Enter POET, PAINTER, JEWELLER, MERCHANT, and MERCER, at several doors POET Good day, sir. PAINTER I am glad y’are well. POET I have not seen you long; how goes the world? PAINTER It wears, sir, as it grows. POET Ay, that’s well known. But what particular rarity? What strange, Which manifold record not matches? See, Magic of bounty, all these spirits thy power Hath conjur’d to attend! I know the merchant. PAINTER I know them both; th’ other’s a jeweller. -

Shakespeare's Annus Mirabilis: Some Structural Aspects of Coriolanus, Timon of Athens and Pericles

-, SH~KESPEARE'S ANNUS MIRABILIS SHAKESPEARE'S ANNUS MIRABILIS: SOME STRUCTURAL ASPECTS OF CORIOLANUS, TIMON OF ATHENS AND PERICLES By BARBARA JANE PANKHURST, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University September 1979 MASTER OF ARTS (1979) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Shakespeare's Annus Mirabilis: Some Structural Aspects of Coriolanus,Timon of Athens and Pericles AUTHOR: Barbara Jane Pankhurst, B.A. (Cantab.) SUPERVISOR: Dr. A.D. Hammond NUMBER OF PAGES: vi, lOB. ii ABSTRACT An investigation of seven aspects of the structure of Shakespeare's Coriolanus, Timon of Athens and Pericles, as a means to understanding the dramatic unity and coherence of the plays. The study is essentially the prolegomena to a more detailed discussion both of those three plays and of those which followed them, and whose structure developed out of theirs. Coriolanus, Timon of Athens and Pericles are seen as the products of an eighteen-month period circa 1607-8, possessed in each case of an effective, integral dramatic structure. The topics selected for consideration to prove that thesis are as follows: 1. The relationship between the hero and fortune~ with particular attention to the patterning of events within the play. This central topic forms the bulk of the first half of the study. 2. The hero's language: rhetoric and a public mode of address. 3. The soliloquy of self-delusion. 4. The use of "sets" of characters, or actions seemingly distinct from the main action. 5. Narrator and observer figures. -

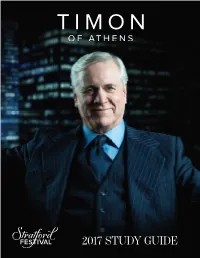

Study Guide 2017 Study Guide

2017 STUDY GUIDE 2017 STUDY GUIDE EDUCATION PROGRAM PARTNER TIMON OF ATHENS BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE DIRECTOR STEPHEN OUIMETTE TOOLS FOR TEACHERS sponsored by PRODUCTION SUPPORT is generously provided by Cec & Linda Rorabeck INDIVIDUAL THEATRE SPONSORS Support for the 2017 Support for the 2017 Support for the 2017 Support for the 2017 season of the Festival season of the Avon season of the Tom season of the Studio Theatre is generously Theatre is generously Patterson Theatre is Theatre is generously provided by provided by the generously provided by provided by Daniel Bernstein & Birmingham family Richard Rooney & Sandra & Jim Pitblado Claire Foerster Laura Dinner CORPORATE THEATRE PARTNER Sponsor for the 2017 season of the Tom Patterson Theatre Cover: Joseph Ziegler. Photography by Lynda Churilla. TABLE OF CONTENTS The Place The Stratford Festival Story ........................................................................................ 1 The Play The Playwright: William Shakespeare ........................................................................ 3 A Shakespearean Timeline ......................................................................................... 4 Plot Synopsis ............................................................................................................... 6 Sources, Origins and Production History .................................................................... 7 Curriculum Connections ............................................................................................. 9 Themes and