Timon of Athens: Know-The-Show Guide — 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timon of Athens: the Iconography of False Friendship

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU English Faculty Publications English Summer 1980 Timon of Athens: The Iconography of False Friendship Clifford Davidson Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/english_pubs Part of the English Language and Literature Commons WMU ScholarWorks Citation Davidson, Clifford, "Timon of Athens: The Iconography of False Friendship" (1980). English Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/english_pubs/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact wmu- [email protected]. Timonof Athens. The Iconographyof False Friendship By CLIFFORD DAVIDSON THE REALIZATION THAT iconographic tableaux appear at central points in the drama of Shakespeare no longer seems to involve a radical critical perspective. Thus a recent study is able to show convincingly that the playwright presented audiences with a Hamlet who upon his first appear- ance on stage illustrated what the Renaissance would certainly have recognized as the melancholic contemplative personality.' As I have noted in a previous article, the hero of Macbeth when he sees the bloody dagger before him is in fact perceiving the image which most clearly denotes tragedy itself; in the emblem books, the dagger is indeed the symbol of tragedy,2 which will be Macbeth's fate if he pursues his bloody course of action. Such tableaux, it must be admitted, are often central to the meaning and the action of the plays. -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 7-24-2018 2:00 PM Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury Jeffrey Daniels The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Neish, Catherine D. The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Geology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Science © Jeffrey Daniels 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Geology Commons, Physical Processes Commons, and the The Sun and the Solar System Commons Recommended Citation Daniels, Jeffrey, "Impact Melt Emplacement on Mercury" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5657. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5657 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Impact cratering is an abrupt, spectacular process that occurs on any world with a solid surface. On Earth, these craters are easily eroded or destroyed through endogenic processes. The Moon and Mercury, however, lack a significant atmosphere, meaning craters on these worlds remain intact longer, geologically. In this thesis, remote-sensing techniques were used to investigate impact melt emplacement about Mercury’s fresh, complex craters. For complex lunar craters, impact melt is preferentially ejected from the lowest rim elevation, implying topographic control. On Venus, impact melt is preferentially ejected downrange from the impact site, implying impactor-direction control. Mercury, despite its heavily-cratered surface, trends more like Venus than like the Moon. -

GREAT Day 2007 Program

Welcome to SUNY Geneseo’s First Annual G.R.E.A.T. Day! Geneseo Recognizing Excellence, Achievement & Talent Day is a college-wide symposium celebrating the creative and scholarly endeavors of our students. In addition to recognizing the achievements of our students, the purpose of G.R.E.A.T. Day is to help foster academic excellence, encourage professional development, and build connections within the community. The G.R.E.A.T. Day Planning Committee: Doug Anderson, School of the Arts Anne Baldwin, Sponsored Research Joan Ballard, Department of Psychology Anne Eisenberg, Department of Sociology Charlie Freeman, Department of Physics & Astronomy Tom Greenfield, Department of English Anthony Gu, School of Business Koomi Kim, School of Education Andrea Klein, Scheduling and Special Events The Planning Committee would like to thank: Stacie Anekstein, Ed Antkoviak, Brian Bennett, Cassie Brown, Michael Caputo, Sue Chichester, Betsy Colon, Laura Cook, Ann Crandall, Joe Dolce, Tammy Farrell, Carlo Filice, Richard Finkelstein, Karie Frisiras, Ginny Geer-Mentry, Becky Glass, Dave Gordon, Corey Ha, John Haley, Doug Harke, Gregg Hartvigsen, Tony Hoppa, Paul Jackson, Ellen Kintz, Nancy Johncox, Enrico Johnson, Ken Kallio, Jo Kirk, Sue Mallaber, Mary McCrank, Nancy Newcomb, Elizabeth Otero, Tracy Paradis, Jennifer Perry, Jewel Reardon, Ed Rivenburgh, Linda Shepard, Bonnie Swoger, Helen Thomas, Pam Thomas, and Taryn Thompson. Thank you to President Christopher Dahl and Provost Katherine Conway-Turner for their support of G.R.E.A.T. Day. Thank you to Lynn Weber for delivering our inaugural keynote address. The G.R.E.A.T. Day name was suggested by Elizabeth Otero, a senior Philosophy major. -

Toward High-Resolution Global Topography of Mercury From

Planetary and Space Science 142 (2017) 26–37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Planetary and Space Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pss Toward high-resolution global topography of Mercury from MESSENGER MARK orbital stereo imaging: A prototype model for the H6 (Kuiper) quadrangle ⁎ Frank Preuskera, , Alexander Starkb, Jürgen Obersta,b,c, Klaus-Dieter Matza, Klaus Gwinnera, Thomas Roatscha, Thomas R. Wattersd a German Aerospace Center, Institute of Planetary Research, D-12489 Berlin, Germany b Technische Universität Berlin, Institute of Geodesy and Geoinformation Science, D-10623 Berlin, Germany c Moscow State University for Geodesy and Cartography, RU-105064 Moscow, Russia d Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560-0315, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: We selected approximately 10,500 narrow-angle camera (NAC) and wide-angle camera (WAC) images of Mercury Mercury acquired from orbit by MESSENGER's Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) with an average resolution MESSENGER of 150 m/pixel to compute a digital terrain model (DTM) for the H6 (Kuiper) quadrangle, which extends from Stereo photogrammetry 22.5°S to 22.5°N and from 288.0°E to 360.0°E. From the images, we identified about 21,100 stereo image Topography combinations consisting of at least three images each. We applied sparse multi-image matching to derive Hun Kal approximately 250,000 tie-points representing 50,000 ground points. We used the tie-points to carry out a DTM photogrammetric block adjustment, which improves the image pointing and the accuracy of the ground point positions in three dimensions from about 850 m to approximately 55 m. -

KPBS September TV Lisitings

SEPTEMBER Programming Schedule Listings are as accurate as possible at press time but are subject to change due to updated programming. For complete up-to-date listings, including overnight programs, visit kpbs.org/tv, or call (619) 594-6983. KPBS Schedule At-A-Glance MONDAY - FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 5:00 AM CLASSICAL STRETCH 5:30 AM YOGA Visit Visit www.kpbs.org/tv www.kpbs.org/tv 6:00 AM PEG + CAT for schedule information for schedule information 6:30 AM ARTHUR 7:00 AM READY JET GO! SESAME STREET SESAME STREET DANIEL TIGER'S DANIEL TIGER'S 7:30 AM NATURE CAT NEIGHBORHOOD NEIGHBORHOOD PINKALICIOUS & PINKALICIOUS & 8:00 AM WILD KRATTS PETERRIFIC PETERRIFIC 8:30 AM MOLLY OF DENALI CURIOUS GEORGE CURIOUS GEORGE 9:00 AM CURIOUS GEORGE LET’S GO LUNA LETS GO LUNA 9:30 AM LET’S GO LUNA NATURE CAT NATURE CAT 10:00 AM DANIEL TIGER WASHINGTON WEEK 10:30 AM DANIEL TIGER Visit KPBS ROUNDTABLE www.kpbs.org/tv 11:00 AM SESAME STREET for schedule information A GROWING PASSION GROWING A 11:30 AM PINKALICIOUS & PETTERIFIC GREENER WORLD 12:00 PM DINOSAUR TRAIN THIS OLD HOUSE 12:30 PM CAT IN THE HAT KNOWS ABOUT THAT! ASK THIS OLD HOUSE NEW SCANDINAVIAN 1:00 PM SESAME STREET COOKING 1:30 PM SPLASH AND BUBBLES JAMIE’S FOOD Visit www.kpbs.org/tv 2:00 PM PINKALICIOUS & PETERRIFIC AMERICA’S TEST KITCHEN for schedule information 2:30 PM LET’S GO LUNA! MARTHA STEWART MEXICO ONE PLATE 3:00 PM NATURE CAT AT A TIME 3:30 PM WILD KRATTS CROSSING SOUTH KEN KRAMER’S 4:00 PM MOLLY OF DENALI RICK STEVES EUROPE ABOUT SAN DIEGO HISTORIC PLACES 4:30 PM ODD SQUAD KPBS/ARTS WITH ELSA SEVILLA PBS NEWSHOUR PBS NEWSHOUR 5:00 PM KPBS EVENING EDITION WEEKEND WEEKEND FIRING LINE WITH 5:30 PM NIGHTLY BUSINESS REPORT KPBS ROUNDTABLE MARGARET HOOVER 6:00 PM BBC WORLD NEWS Visit 6:30 PM KPBS EVENING EDITION LAWRENCE WELK www.KPBS.org/TV for schedule information 7:00 PM PBS NEWSHOUR KPBS-TV Programming Schedule – SEPTEMBER 2019 1 Sunday, September 1 11:00 KPBS Retire Safe & Secure with Ed Slott 2019 America needs Ed Slott now 6:00PM PBS Previews: Country Music KPBS more than ever. -

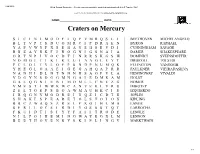

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km. -

Discourses of Femininity in Thomas Shadwell's Adaptation of Timon Of

Outskirts Vol. 38, 2018, 1-17 “What gay, vain, pratting thing is this”: Discourses of femininity in Thomas Shadwell’s adaptation of Timon of Athens Melissa Merchant During the Restoration era (1660 to 1700), the plays of Shakespeare were routinely adapted in order to make them fit for the new stages and society in which they were being produced. Representations ‘femininity’ and ‘woman’ were re-negotiated following a tumultuous period in English history and the evidence of this can be seen in the Shakespearean adaptations. Theatrical depictions of women within the plays produced during this time drew on everyday discourses of femininity and were influenced by the new presence of professional actresses on the London stages. In a time before widespread literacy and access to multiple media platforms, the theatre served a didactic function as a site which could present “useful and instructive representations of human life" (as ordered by Charles II in his Letters Patent to the theatre companies in 1662). This paper argues that, on the stage, Restoration women were afforded three roles: gay, ideal or fallen. Each of these are evident within Thomas Shadwell’s adaptation of Timon of Athens. Introduction “Women are of two sorts,” claimed Bishop Aylmer during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, some were “wiser, better learned, discreeter, and more constant than a number of men” and the other “worse sort of them” were: Fond, foolish, wanton, flibbergibs, tattlers, triflers, wavering, witless, without council, feeble, careless, rash, proud, dainty, tale-bearers, eavesdroppers, rumour-raisers, evil-tongued, worse-minded, and in every way doltified with the dregs of the devil’s dunghill (Stretton 2005, 52). -

Olivia's Household John W. Draper PMLA, Vol. 49, No. 3. (Sep., 1934)

Olivia's Household John W. Draper PMLA, Vol. 49, No. 3. (Sep., 1934), pp. 797-806. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0030-8129%28193409%2949%3A3%3C797%3AOH%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z PMLA is currently published by Modern Language Association. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mla.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Sat Feb 9 20:31:37 2008 XLIII OLIVIA'S HOUSEHOLD P Shakespeare's plays, as is generally admitted, are incomparably I greater than their sources, their greatness must inhere mainly in his changes and additions. -

Article (Published Version)

Article 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon ERNE, Lukas Christian Reference ERNE, Lukas Christian. 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon. Modern Philology, 2010, vol. 107, no. 3, p. 493-505 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14484 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 492 MODERN PHILOLOGY absorbs and reinterprets a vast array of Renaissance cultural systems. "Our other Shakespeare": Thomas Middleton What is outside and what is inside, the corporeal world and the mental and the Canon one, are "similar"; they are vivified and governed by the divine spirit in Walker's that emanates from the Sun, "the body of the anima mundi" LUKAS ERNE correct interpretation. 51 Campanella's philosopher has a sacred role, in that by fathoming the mysterious dynamics of the real through scien- University of Geneva tific research, he performs a religious ritual that celebrates God's infi- nite wisdom. To T. S. Eliot, Middleton was the author of "six or seven great plays." 1 It turns out that he is more than that. The dramatic canon as defined by the Oxford Middleton—under the general editorship of Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino, leading a team of seventy-five contributors—con- sists of eighteen sole-authored plays, ten extant collaborative plays, and two adaptations of plays written by someone else. The thirty plays, writ ten for at least seven different companies, cover the full generic range of early modern drama: eight tragedies, fourteen comedies, two English history plays, and six tragicomedies. These figures invite comparison with Shakespeare: ten tragedies, thirteen comedies, ten or (if we count Edward III) eleven histories, and five tragicomedies or romances (if we add Pericles and < Two Noble Kinsmen to those in the First Folio). -

The Republican Journal: Vol. 70, No. 52

The Republican Journal. Ml 70._ BELFAST, MAINE. THURSDAY, DECEMBER 29, 1898. NIMBLE777 Washington Whisperings. There is Christmas .Services. belief in some ;he Christ. Sucb » great I ami character of its Founder aud Initiator. PERSONAL. PERSONAL. every evidence that the war is # journal. department lersouality, some almost superhuman being Jesus is to the world of men no [EPUBLICAN strenuous the nation from legendary making efforts to put The services at the ;hat shall >w and deliver no of enough Unitarian church on hero, phantom superstition, no fabled has been a common T. S. Ford of Swanville went to Amerioan troops into Cuba to meet any oppression or bondage, reason of the Togas Homer came home from Christmas morning were being existing by ingenious Dickey Union to liM'AY .VOK.MKG BY THE according to the belief m al of the early nations and races. call through the speedy evacuation of the credulity of men, he is more real and pow- Monday to do work. announced last were in the darkness evangelistic spend Christinas. All the program week. The church In proportion as they erful to-day than centuries He ■ Spanish garrison. transports when, ago, Pub. Co. was and of affliction aud national adversity, the walked in Dr. P. E. Luce of Waterville was in Bel- Orrin J. f 1' Journal available in the Atlantic are neatly appropriately and flesh ami blood the Gallileeau Dickey spent Christinas with ports being decorated, and was their faith in the _ the discourse the stronger deeper hills and the Judean plains. Strange and fast Monday on business. -

A Map of the Intra-Ejecta Plains of the Caloris Basin, Mercury

43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2012) 1844.pdf A MAP OF THE INTRA-EJECTA DARK PLAINS OF THE CALORIS BASIN, MERCURY. D.L. Buczkowski and K.D. Seelos, Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD 20723, [email protected]. Introduction: Two Mercury quadrangles based on High-resolution mapping of the intra-ejecta dark Mariner 10 data cover the Caloris basin (Fig. 1): H-8 plains: We are using high resolution imaging data Tolstoj [1] and H-3 Shakespeare [2]. The dark annulus from the MDIS instrument to create a new geomorphic identified in MESSENGER data corresponds well to map of the dark annulus around the Caloris basin. We the mapped location of certain formations [3], primari- also utilize a principle component map [3] to distin- ly the Odin Formation. The Odin Formation is de- guish subtle differences in the color data. In the prin- scribed in the quadrangle maps as a unit of low, closely ciple component map green represents the second prin- spaced knobs separated by a smooth, plains-like ma- ciple component (PC2), which reflects variations be- terial and was interpreted as ejecta from the Caloris tween light and dark materials. Meanwhile, red is the impact. Schaber and McCauley [1980] observed that inverted PC2 and blue is the ratio of normalized reflec- the intra-ejecta plains in the Odin Formation resemble tance at 480/1000 nm, which highlights fresh ejecta. the Smooth Plains unit that was also prevalent in the We are mapping all contacts between bright and H-8 and H-3 quadrangles outside of Caloris.