The Power of Place in Connecticut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York, New York

EXPOSITION NEW YORK, NEW YORK Cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo Du 14 juillet au 10 septembre 2006 Grimaldi Forum - Espace Ravel INTRODUCTION L’exposition « NEW YORK, NEW YORK » cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo produite par le Grimaldi Forum Monaco, bénéficie du soutien de la Compagnie Monégasque de Banque (CMB), de SKYY Vodka by Campari, de l’Hôtel Métropole à Monte-Carlo et de Bentley Monaco. Commissariat : Lisa Dennison et Germano Celant Scénographie : Pierluigi Cerri (Studio Cerri & Associati, Milano) Renseignements pratiques • Grimaldi Forum : 10 avenue Princesse Grace, Monaco – Espace Ravel. • Horaires : Tous les jours de 10h00 à 20h00 et nocturne les jeudis de 10h00 à 22h00 • Billetterie Grimaldi Forum Tél. +377 99 99 3000 - Fax +377 99 99 3001 – E-mail : [email protected] et points FNAC • Site Internet : www.grimaldiforum.mc • Prix d’entrée : Plein tarif = 10 € Tarifs réduits : Groupes (+ 10 personnes) = 8 € - Etudiants (-25 ans sur présentation de la carte) = 6 € - Enfants (jusqu’à 11 ans) = gratuit • Catalogue de l’exposition (versions française et anglaise) Format : 24 x 28 cm, 560 pages avec 510 illustrations Une coédition SKIRA et GRIMALDI FORUM Auteurs : Germano Celant et Lisa Dennison N°ISBN 88-7624-850-1 ; dépôt légal = juillet 2006 Prix Public : 49 € Communication pour l’exposition : Hervé Zorgniotti – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 02 – [email protected] Nathalie Pinto – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 03 – [email protected] Contact pour les visuels : Nadège Basile Bruno - Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 25 – [email protected] AUTOUR DE L’EXPOSITION… Grease Etes-vous partant pour une virée « blouson noir, gomina et look fifties» ? Si c’est le cas, ne manquez pas la plus spectaculaire comédie musicale de l’histoire du rock’n’roll : elle est annoncée au Grimaldi Forum Monaco, pour seulement une semaine et une seule, du 25 au 30 juillet. -

Billboard-1987-11-21.Pdf

ICD 08120 HO V=.r. (:)r;D LOE06 <0 4<-12, t' 1d V AiNE3'c:0 AlNClh 71. MW S47L9 TOO, £L6LII.000 7HS68 >< .. , . , 906 lIOIa-C : , ©ORMAN= $ SPfCl/I f011I0M Follows page 40 R VOLUME 99 NO. 47 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT November 21, 1987/$3.95 (U.S.), $5 (CAN.) CBS /Fox Seeks Copy Depth Many At Coin Meet See 45s As Strong Survivor with `Predator' two -Pack CD Jukeboxes Are Getting Big Play "Predator" two-pack is Jan. 21; indi- and one leading manufacturer Operators Assn. Expo '87, held here BY AL STEWART vidual copies will be available at re- BY MOIRA McCORMICK makes nothing else. Also on the rise Nov. 5-7 at the Hyatt Regency Chi- NEW YORK CBS /Fox Home Vid- tail beginning Feb. 1. CHICAGO While the majority of are video jukeboxes, some using la- cago. More than 7,000 people at- eo will test a novel packaging and According to a major -distributor jukebox manufacturers are confi- ser technology, that manufacturers tended the confab, which featured pricing plan in January, aimed at re- source, the two -pack is likely to be dent that the vinyl 45 will remain a say are steadily gaining in populari- 185 exhibits of amusement, music, lieving what it calls a "critical offered to dealers for a wholesale viable configuration for their indus- ty. and vending equipment. depth -of-copy problem" in the rent- price of $98.99. Single copies, which try, most are beginning to experi- Those were the conclusions Approximately 110,000 of the al market. -

Crinew Music Re Uoft

CRINew Music Re u oft SEPTEMBER 11, 2000 ISSUE 682 VOL. 63 NO. 12 WWW.CMJ.COM MUST HEAR Universal/NIP3.com Trial Begins With its lawsuit against MP3.com set to go inent on the case. to trial on August 28, Universal Music Group, On August 22, MP3.com settled with Sony the only major label that has not reached aset- Music Entertainment. This left the Seagram- tlement with MP3.com, appears to be dragging owned UMG as the last holdout of the major its feet in trying to reach a settlement, accord- labels to settle with the online company, which ing to MP3.com's lead attorney. currently has on hold its My.MP3.com service "Universal has adifferent agenda. They fig- — the source for all the litigation. ure that since they are the last to settle, they can Like earlier settlements with Warner Music squeeze us," said Michael Rhodes of the firm Group, BMG and EMI, the Sony settlement cov- Cooley Godward LLP, the lead attorney for ers copyright infringements, as well as alicens- MP3.com. Universal officials declined to corn- ing agreement allowing (Continued on page 10) SHELLAC Soundbreak.com, RIAA Agree Jurassic-5, Dilated LOS AMIGOS INVIWITI3LES- On Webcasting Royalty Peoples Go By Soundbreak.com made a fast break, leaving the pack behind and making an agreement with the Recording Word Of Mouth Industry Association of America (RIAA) on aroyalty rate for After hitting the number one a [digital compulsory Webcast license]. No details of the spot on the CMJ Radio 200 and actual rate were released. -

School Sports About to Return

Volume 42 Number 4 Thursday, January 28, 2021 24 Pages | 75¢ School sports about to return By Dan Zobel The only exception is that In a matter of just a cou- indoor medium-risk sports ple of weeks, the outlook can only have contests on youth sports for the re- within their conference or mainder of the school year COVID region. has changed dramatically. The Illinois High School Since late November, zero Association board met Jan- sports, no matter what risk uary 27 to set season sched- label the Illinois Depart- ules for the remainder of ment of Public Health de- the school year. termined they were, have The original winter sea- been allowed to compete. son, which includes basket- That changed earlier this ball and bowling, is set to month, when Governor J.B. end soon. While the origi- Pritzker lifted the state- nal spring season, which wide COVID-19 Tier 3 miti- includes volleyball, football gation mandate. and boys soccer, is sched- Since then, all of the 11 re- uled to start with practice gions have advanced out of February 15. Shown is the vehicle after Steeleville firemen extricated victim Maria Jacinto. Tier 3, some as far as back One caveat to competition into Phase 4 of Pritzker’s is that masks are manda- Restore Illinois plan. One tory in practice and games. Woman saved from burning car of those regions to reach Social distancing must be that phase is Region 5, followed for players on the which includes Perry and bench and game personnel. Brothers, bystander carried water in trash can Jackson counties. -

Talking Heads from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Talking Heads From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Background information Origin New York City, New York, United States Genres New wave · post-punk · art pop · funk rock · worldbeat Years active 1975–1991 Labels Sire/Warner Bros., EMI Associated acts Tom Tom Club, The Modern Lovers, Brian Eno Past members David Byrne Chris Frantz Tina Weymouth Jerry Harrison Talking Heads were an American rock band formed in 1975 in New York City and active until 1991. The band comprised David Byrne (lead vocals, guitar), Chris Frantz (drums), Tina Weymouth (bass) and Jerry Harrison (keyboards, guitar). Other musicians also regularly made appearances in concert and on the group's albums. The new wave style of Talking Heads combined elements of punk, art rock, funk, avant-garde, dance, pop, and world music with the neurotic, whimsical stage persona of frontman and songwriter David Byrne. The band made use of various performance and multimedia projects throughout its career. Critic Stephen Thomas Erlewine described Talking Heads as being "one of the most critically acclaimed bands of the '80s, while managing to earn several pop hits." In 2002, the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Four of the band's albums appeared on Rolling Stone's list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time and three of their songs ("Psycho Killer", "Life During Wartime", and "Once in a Lifetime") were included among The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. Talking Heads were also included at #64 on VH1's list of the "100 Greatest Artists of All Time", placed among Rolling Stone 's similar list as well. -

Rip “Her” to Shreds

Rip “Her” To Shreds: How the Women of 1970s New York Punk Defied Gender Norms Rebecca Willa Davis Senior Thesis in American Studies Barnard College, Columbia University Thesis Advisor: Karine Walther April 18, 2007 Contents Introduction 2 Chapter One Patti Smith: Jesus Died For Somebody’s Sins But Not Mine 11 Chapter Two Deborah Harry: I Wanna Be a Platinum Blonde 21 Chapter Three Tina Weymouth: Seen and Not Seen 32 Conclusion 44 Bibliography 48 1 Introduction Nestled between the height of the second wave of feminism and the impending takeover of government by conservatives in 1980 stood a stretch of time in which Americans grappled with new choices and old stereotypes. It was here, in the mid-to-late 1970s, that punk was born. 1 Starting in New York—a city on the verge of bankruptcy—and spreading to Los Angeles and London, women took to the stage, picking punk as their Trojan Horse for entry into the boy bastion of rock’n’roll. 2 It wasn’t just the music that these women were looking to change, but also traditionally held notions of gender as well. This thesis focuses on Patti Smith, Deborah Harry, and Tina Weymouth—arguably the first, and most important, female punk musicians—to demonstrate that women in punk used multiple methods to question, re-interpret, and reject gender. On the surface, punk appeared just as sexist as any other previous rock movement; men still controlled the stage, the sound room, the music journals and the record labels. As writer Carola Dibbell admitted in 1995, “I still have trouble figuring out how women ever won their place in this noise-loving, boy-loving, love-fearing, body-hating music, which at first glance looked like one more case where rock’s little problem, women, would be neutralized by male androgyny.” According to Dibbell, “Punk was the music of the obnoxious, permanently adolescent white boy—skinny, zitty, ugly, loud, stupid, fucked up.”3 Punk music was loud and aggressive, spawning the violent, almost exclusively-male mosh pit at live shows that still exists today. -

Turnerian Rebel

DBS SCHOOL OF ARTS TURNERIAN REBEL UNCOVERING THE ANTHROPOLOGIST VICTOR TURNER’S LIMINALITY IN MODERN PERFORMANCE LAURA MONKS MAY 2014 SUPERVISOR: DR PAUL HOLLYWOOD THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE BA (HONS) FILM, LITERATURE AND DRAMA Abstract This thesis shall utilize the anthropological studies of Victor Turner to focus on the capacity for an individual, or Turnerian Rebel, to induce ambiguous, and thus possibly revolutionary, symbolic exchange on the musical and theatrical stage. Many Western twentieth century cultural theorists, including Jean Baudrillard, view that traditional forms of social communication have become increasingly attenuated in the light of technology, industry and capitalism. As a consequence the possibility for rebellious social drama is dampened. Through the prism of such critique the discussion will focus on the potential that remains in artistic performance. Firstly there will be an exploration of Turner’s concepts of breach, liminality and communitas, originally observed in ritual and social drama of the Nbemdu African tribe in the nineteen fifties and sixties. This will identify the dynamic nature of social structures and, through symbolic performance, the possibility for the liminal individual to ignite a change or alteration. After which works by playwright Sarah Kane and musician David Byrne shall be analysed to conceive their own rebellious liminality. Ultimately by exposing their breach of social norms, identify the capacity of the modern Turnerian Rebel to create new possibilities for their community. 1 Acknowledgements Thank you to my supervisor Dr. Paul Hollywood for his support and guidance not only with my thesis but over the last four college years. -

Synopsis CPL 1

General and PG titles Call: 1-800-565-1996 Criterion Pictures 30 MacIntosh Blvd., Unit 7 • Vaughan, Ontario • L4K 4P1 800-565-1996 Fax: 866-664-7545 • www.criterionpic.com 10,000 B.C. 2008 • 108 minutes • Colour • Warner Brothers Director: Roland Emmerich Cast: Nathanael Baring, Tim Barlow, Camilla Belle, Cliff Curtis, Joel Fry, Mona Hammond, Marco Khan, Reece Ritchie A prehistoric epic that follows a young mammoth hunter's journey through uncharted territory to secure the future of his tribe. The 11th Hour 2007 • 93 minutes • Colour • Warner Independent Pictures Director: Leila Conners Petersen, Nadia Conners Cast: Leonardo DiCaprio (narrated by) A look at the state of the global environment including visionary and practical solutions for restoring the planet's ecosystems. 13 Conversations About One Thing 2001 • 102 minutes • Colour • Mongrel Media Director: Jill Sprecher Cast: Matthew McConaughey, David Connolly, Joseph Siravo, A.D. Miles, Sig Libowitz, James Yaegashi In New York City, the lives of a lawyer, an actuary, a house-cleaner, a professor, and the people around them intersect as they ponder order and happiness in the face. of life's cold unpredictability. 16 Blocks 2006 • 102 minutes • Colour • Warner Brothers Director: Richard Donner Cast: Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David Morse, Alfre Woodard, Nick Alachiotis, Brian Andersson, Robert Bizik, Shon Blotzer, Cylk Cozart Based on a pitch by Richard Wenk, the mismatched buddy film follows a troubled NYPD officer who's forced to take a happy, but down-on- his-luck witness 16 blocks from the police station to 100 Centre Street, although no one wants the duo to make it. -

Music Guide '89 for Big Play Match & Win Cash Prizes

Music Guide '89 For Big Play Match & Win Cash Prizes J ENUFF V NUFF (ATCO) RADIO & RECORDS 41 KATHY MATTEA (MERCURY) 1927 (ATLANTIC) V 1 MELISSA ETHERIDGE (ISLAND) V :t//1!K a .Y... r,i ,. _ : r 6 ' % .n; Gvti# . MICHAEL McDONALD (FEPRISE) V 10DB (CRUSH K -TEL) Y 3 MARY'S DANISH (CHAMELEON) A BANG TANGO P. (MECHANIC/MCA) A MARY CHAPIN CARPENTER (COLUMBIA/CBS NASHVILLE) 1- OUEENSRYCHE (EMI) V NONA HENDRYX (PRIVATE MUSIC) o r. ¡ 1t IA +. 11 -<. r o a f , S 'IIT ° 1:¿S*111110: il- z A BAD ENGLISH (EPIC) GREGSON A 8 COLLISTER (RHINO) \ i D.A.D (WB) ,41/ i I 4 4 / A RICHARD SOUTHER (NARADA) -i . f _ ;l --_... 14'I, , á XYZ (ENIGMA) , A BILLY JOEL (COLUMBIA) -r r ' l A JUNKYARD (GEFFEN) 41 TREVOR RABIN (ELEKTRA) LENNY KRAVITZ (VIRGIN) More Than 650 New Releases WHAT CAN YOU EXPECT FROV COMPANY THAT BRINGS YOU THE MOST VARIED AND IVATING "USIC IN THE BUSINESS? MORE OF THE SAME! BRNK,S, -r STEPHEN E Ñ 1195P BANKSTATEMENT STEPHEN BISHOP DIRTY LOOKS BANKSTATEMENT (82007) BOWLING IN PARIS (87920) TURN OF THE SCREW (81992) JASON DONOVAN IIIKJONLS TEN GOOD REASONS .. a 4111 Tra#, AW . 11 A I 7.1 4 A 1 K M EA X . JASON DONOVAN MICK JONES MAX Q TEN GOOD REASONS (82oos) MICK JONES (81991) MAX O (82014) _ ' _, MGIM TGNEL,.L . .. 1":7 ..e11hKyll9, ,..... e i .n .. 192 _ : < . 1\IÁfyl ie a _---" ' c ir: ü . ilf i o o If - »S é. 0. e , A tr ° 4 M o o ishf= -'. -

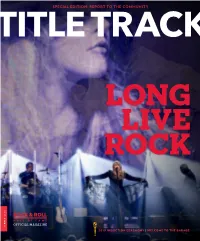

Report to the Community Title Track

SPECIAL EDITION: REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY TITLE TRACK LONG LIVE ROCK OFFICIAL MAGAZINE SUMMER 2019 2019 INDUCTION CEREMONY / WELCOME TO THE GARAGE W WELCOME FROM THE CEO Thanks to you, this was a record-breaking year at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. We are grateful for your friendship and support. I am excited to recap the year and drive home how your continued support impacts this great museum. Here are just a few highlights: We hosted 580,000 visitors in Cleveland, our largest annual impact since opening, and reached millions through our digital channels. We increased accessibility for all by making the museum free to Cleveland residents, thanks to a generous $10 million grant from KeyBank. Rock Hall Live!, powered by PNC, featured 80-plus live outdoor music events ranging from local bands to large-scale productions with artists like Social Distortion and 2014 Inductee John Oates. Over 50,000 students experienced the power of rock & roll through our exhibits and award-winning programs, Rockin’ the Schools and Toddler Rock. We hosted a fantastic Cleveland Induction in 2018—which had a $36.5 million economic impact on the city—and did it all over again in Brooklyn in 2019. We became the first music museum in the world to receive sensory-inclusion certification so that all visitors can experience the museum in the most impactful way. A record number of 2,300 artists stopped by the Rock Hall and inspired us with their gratitude and stories. To amplify this report with deeper content and videos, go to rockhall.com/annual-report. -

Past Connecticut Arts Awards Recipients

History of Recipients Connecticut Arts Awards 1981 (continued) Pilobolus 1978 Maurice Sendak, Author and illustrator of children’s Marian Anderson, Singer books Robert Motherwell, Painter and printmaker Cesar Pelli, Architect Lippincott, Inc., Public sculpture fabricators Peace Train Foundation / Paul LeMay, Fiddler 1982 and founder of the New England Fiddle Contest Victor Borge, Musician and humorist Patricia Edwards/Valley Arts Center Brookfield Craft Center Juan Fuentes, Photographer Gerry Mulligan, Saxophonist Mildred Dunnock, Actress Lloyd Richards, Actor, director and Dean of Yale Arthur Miller, Playwright School of Drama Moshe Paranov, Pianist and founder of Hartt School of Margo Rose, Puppeteer Music, Hartford United Technologies Corp. Mary Hunter Wolf, Theater director and producer 1983 1979 Willian Benton Art Museum Bowen-Peters School of Dance Arvin Brown, Theater and television director Malcolm Cowley, Literary artist Greater Hartford Arts Council Ralph Kirkpatrick, Musician Jackie McLean, Jazz saxophonist and co-founder of Meriden Gravure Company Artists Collective, Hartford Ruben Nakian, Sculptor James Merrill, Poet National Theatre of the Deaf New Britain Museum of Art 1984 Menen Osario William Styron, Novelist and essayist Wadsworth Atheneum 1980 City Spirit Artists Artists Collective Champion International Peter Blume, Painter and sculptor Lucia Chase, Dancer and actress 1985 Eva LeGallienne, Actress No awards given Newton Schenck, Founder of New Haven’s Long Wharf Theatre 1986 Robert Penn Warren, Poet and novelist Betty Jones, Singer Michael Price, Arts administrator (Goodspeed Musicals, 1981 East Haddam) Morris Carnovsky, Actor James Laughlin, Poet Community Renewal Team Craftery Gallery Barbara Tuchman, Historian and author Curbstone Press Anthony S. Keller, Advocate for creation of state arts 1987 councils. -

Sponsorship Opportunities

6:30-7 P.M. | Cocktails and Conversation 7:00- 8:00 P.M. | Induction Ceremony 2020 Inductees Connecticut Suffragists Josephine Bennett Sarah Lee Brown Fleming Frances Ellen Burr Clara, Helena, and Elsie Hill Catherine Flanagan Emily Pierson Sponsorship Proposal For more information please contact Pam Dougherty | [email protected] Sponsporships At - A - Glance “Did You Company Logo on Mention in Sponsor Sponsorship Welcome Commercial Know” Website, Social Media Investment Event Tickets Media Level Opportunities Video Spot Video Platforms and all Outreach (10 sec) Marketing Materials Title $10,000 Lead Sponsor 30 Seconds Unlimited Sponsorship Gold Spotlight $7,500 Activity Room 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Activity Room Gold Spotlight Centenninal $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Exclusive Prize Package Activity Room Gold Spotlight $7,500 Mirror Mirror 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Room Gold Spotlight Women Who $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Run Room Gold Spotlight Show Me the $7,500 20 Seconds Unlimited Premier Chat Money Room General Chat Silver $5,000 15 Seconds Unlimited Room Bronze $3,000 Logo Listing Unlimited Why Your Sponsorship Matters COVID-19 has created many challenges for our community, and women and students are particularly impacted. At the Hall, we are working diligently to ensure that our educational materials are available online while parents, students, and community members work from home and that our work remains relevant to the times. We are moving forward to offer even more programs that support our community’s educational needs, from collaborating with our Partners to offer virtual educational events like at-home STEM workshops, to our new webinar series, “A Conversation Between”, which creates a forum for women to discuss issues that matter to them with leaders in our community.