1 from Mesopotamia to the Nebraska State Capitol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artist: Period/Style: Patron: Material/Technique: Form

TITLE: Apollo 11 Stones LOCATION: Namibia DATE: 25,500-25,300 BCE ARTIST: PERIOD/STYLE: Mesolithic Stone Age PATRON: MATERIAL/TECHNIQUE: FORM: The Apollo 11 stones are a collection of grey-brown quartzite slabs that feature drawings of animals painted with charcoal, clay, and kaolin FUNCTION: These slabs may have had a more social function. CONTENT: Drawings of animals that could be found in nature. On the cleavage face of what was once a complete slab, an unidentified animal form was drawn resembling a feline in appearance but with human hind legs that were probably added later. Barely visible on the head of the animal are two slightly-curved horns likely belonging to an Oryx, a large grazing antelope; on the animal’s underbelly, possibly the sexual organ of a bovid. CONTEXT: Inside the cave, above and below the layer where the Apollo 11 cave stones were found, archaeologists unearthed a sequence of cultural layers representing over 100,000 years of human occupation. In these layers stone artifacts, typical of the Middle Stone Age period—such as blades, pointed flakes, and scraper—were found in raw materials not native to the region, signaling stone tool technology transported over long distances.Among the remnants of hearths, ostrich eggshell fragments bearing traces of red color were also found—either remnants of ornamental painting or evidence that the eggshells were used as containers for pigment. Approximately 25,000 years ago, in a rock shelter in the Huns Mountains of Namibia on the southwest coast of Africa (today part of the Ai-Ais Richtersveld Transfrontier Park), an animal was drawn in charcoal on a hand-sized slab of stone. -

St. Bartholomew's Church and Community House: Draft Nomination

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: St. Bartholomew’s Church and Community House Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 325 Park Avenue (previous mailing address: 109 East 50th Street) Not for publication: City/Town: New York Vicinity: State: New York County: New York Code: 061 Zip Code: 10022 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: District: Public-State: Site: Public-Federal: Structure: Object: Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 2 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: DRAFT NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 ST. BARTHOLOMEW’S CHURCH AND COMMUNITY HOUSE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

The City of Aššur and the Kingdom of Assyria: Historical Overview

Assurlular Dicle'den Toroslar'a Tann Assur'un Kralhg1 The Assyrians .hm11.dum uf tltc (;,,._[ l ur ltm•J T1g1l '' Trmru~ Assur Kenti ve Assur Krall1g1 Tarihine Genel Baki§ The City of Assur and the Kingdom of Assyria: Historical Overview KAREN RADN ER* Assur medeniyetinin arkeolojik ke~fi MS 19. yüz}'ll ortalannda Tb.: a1< h.tcologu:al discoven ol A•sH ra brWJn m tlat mi•ll\1'1' et·tlf1H Y \0 (L1.rsen l!l\11)) >\1 rhat ume, ba~lamt~tJr (Larsen 1996). 0 zamanlarda Osmanh imparator frcnc h nnd Ar iri~h dip1om m ;md 1racl.- eh if•galt''i sta lugu topraklarmda görev yapan Franstz ve ingiliz diplomatlar uotwrl in thc Olll man Emp1re us d theu spare llme ile ticari temsilciler bo~ zamanlannda Musul kenti ~evresinde 10 c.;xplort' tht• rq~ion .mmnd Iht> < ity ot Mosul :md ke§if gczileri yaparken; inive, Kalhu ve Dur-~arrukin'de ki tlllcU\ercd the r<:mö&ins nftht' tO):&I cilie' ol ~mt wh, k.raliyet kentlerinin k.almulanm ortaya <;tkarmt§lardL Eski K.. ll•u nml Dur-~aa rukcn. Thc• cll~ro\• ry ot a lo5t civ1 Ji?~tinu wr1h .1 ~troug Bihlir .tl comwnion com Ahit ile gü~lü bir baglantlSt olan bu kaytp medeniyetin ke~ cidcd w1th thc creation of gr ancl nun. urns in l'.urs fi, Paris ve Londra'da bir yandan halk1 egiten bir yandan ,tnd l.onrlon tlr.•I '"11~h1 to t>dtiCllll' !Iw puhlic \\lalle da imparatorluklarm dünyayt sarsan gücünü orlaya koyma simuh.m.. uush clemtHISII.tling 1h• impt:tl.tl p<mer s' Y' ama<;layan büyük müzelerin kurulmaslyla aynt zarnanda hold OH'r the wotld, and '\ss} aan galletrc 1\"de Cle ated iu holh tht Lolll~< 31111!111' lhitish l\ ln~cum . -

The British Museum Annual Reports and Accounts 2019

The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 HC 432 The British Museum REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2020 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Museums and Galleries Act 1992 Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed on 19 November 2020 HC 432 The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 © The British Museum copyright 2020 The text of this document (this excludes, where present, the Royal Arms and all departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium provided that it is reproduced accurately and not in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as British Museum copyright and the document title specifed. Where third party material has been identifed, permission from the respective copyright holder must be sought. Any enquiries related to this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]. This publication is available at www.gov.uk/ofcial-documents. ISBN 978-1-5286-2095-6 CCS0320321972 11/20 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fbre content minimum Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Ofce The British Museum Report and Accounts 2019-20 Contents Trustees’ and Accounting Ofcer’s Annual Report 3 Chairman’s Foreword 3 Structure, governance and management 4 Constitution and operating environment 4 Subsidiaries 4 Friends’ organisations 4 Strategic direction and performance against objectives 4 Collections and research 4 Audiences and Engagement 5 Investing -

EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers

TM EDUCATION MATERIALS TEACHER GUIDE Dear Teachers, Top of the RockTM at Rockefeller Center is an exciting destination for New York City students. Located on the 67th, 69th, and 70th floors of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the Top of the Rock Observation Deck reopened to the public in November 2005 after being closed for nearly 20 years. It provides a unique educational opportunity in the heart of New York City. To support the vital work of teachers and to encourage inquiry and exploration among students, Tishman Speyer is proud to present Top of the Rock Education Materials. In the Teacher Guide, you will find discussion questions, a suggested reading list, and detailed plans to help you make the most of your visit. The Student Activities section includes trip sheets and student sheets with activities that will enhance your students’ learning experiences at the Observation Deck. These materials are correlated to local, state, and national curriculum standards in Grades 3 through 8, but can be adapted to suit the needs of younger and older students with various aptitudes. We hope that you find these education materials to be useful resources as you explore one of the most dazzling places in all of New York City. Enjoy the trip! Sincerely, General Manager Top of the Rock Observation Deck 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York NY 101 12 T: 212 698-2000 877 NYC-ROCK ( 877 692-7625) F: 212 332-6550 www.topoftherocknyc.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Teacher Guide Before Your Visit . Page 1 During Your Visit . Page 2 After Your Visit . Page 6 Suggested Reading List . -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type ail entries compiete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Ryons-Alaxander House (LC13:D5-2) and/or common 2. Location street & number 1335 Ryons not for publication city, town Lincoln N/A_ vicinity of congressional district state Nebraska code 031 county Lancaster code 109 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object N/A in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name Roger Dieckhaus street & number 1835 Ryons city, town Lincoln N/A vicinity of state Nebraska 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. City-County Building city, town Lincoln state Nebraska 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Nebraska Historic Buildings Survey "as th»s property been determined elegible? __ yes_____X no date On-going______________________________——federal J-_state __county __local depository for survey records Nebraska State Historical Society state Nebraska 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site _X_good ruins _JL_ altered moved date . N/A f^ir unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Ryons-Alexander house is a two story brick square-type house built in 1908 under the supervision of Charles J. -

The Mythological Tales Which Must Have Been Current Among the Sumerians And

oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ASSYRIOLOGIOAL STUDIES JOHN ALBEBT WILSON and THOMAS GEORGE ALLEN Editors oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu GILGAMESH AND THE HULUPPU-TREV oi.uchicago.edu THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY NEW YORK THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON THE MARTJZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA TOKYO, OSAKA, KYOTO, FTTKTJOKA, SENDAI THE COMMERCIAL PRESS, LIMITED SHANGHAI oi.uchicago.edu THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE of THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ASSYRIOLOGICAL STUDIES, NO. 10 GILGAMESH AND THE HULUPPU-TREE A RECONSTRUCTED SUMERIAN TEXT By SAMUEL N. KRAMER THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PUBLISHED APRIL 1938 PRINTED IN GERMANY BY J.J. AUGUSTIN, GLT)CKSTADT-HAMBURG-NEW YORK oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ix TEXT AND TRANSLATION 1 PROBLEMS IN THE TRANSLATION OF SUMERIAN 11 COMMENTARY ON THE GILGAMESH TEXT 31 vii oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ABL Harper, Robert Francis. Assyrian and Babylonian letters belonging to the Kouyunjik collection of the British Museum (14 vols.; London, 1892-1914). AJSL American journal of Semitic languages and literatures (Chicago etc., 1884 .)• AO Paris. Musee national du Louvre. Antiquites orientales. (Followed by catalogue number.) AOF Archiv fur Orientforschung (Berlin, 1923 ). AS Chicago. University. Oriental Institute. Assyriological studies (Chicago, 1931 ). AS~No. 8 Kramer, Samuel N. The Sumerian prefix forms be- and bi- in the time of the earlier princes of Lagag (1936). ASKT Haupt, Paul. Akkadische und sumerische Keilschrifttexte (Leipzig, 1881-82). BE Pennsylvania. University. The Babylonian expedition of the Uni versity of Pennsylvania. -

Courthouse Sculptor Lee Lawrie Paul D

Stanford Newel, Proposal Rock, and Newell Park Widows Newell Park Celebrates Its Centennial Winter 2009 Volume 43, Number 4 Page 11 Courthouse Sculptor Lee Lawrie Paul D. Nelson —Page 3 Two of Lee Lawrie’s architectural sculptures, Liberty (top) and The People, on the façade of the St. Paul City Hall and Ramsey County Courthouse, Fourth Street entrance. Photo courtesy of Paul D. Nelson. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY RAMSEY COUNTY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 43, Number 4 Winter 2009 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY the mission statement of the ramsey county historical society BOARD OF DIRECTORS adopted by the board of directors on December 20, 2007: J. Scott Hutton The Ramsey County Historical Society inspires current and future generations Past President Thomas H. Boyd to learn from and value their history by engaging in a diverse program President of presenting, publishing and preserving. Paul A. Verret First Vice President Joan Higinbotham Second Vice President C O N T E N T S Julie Brady Secretary 3 Courthouse Sculptor Carolyn J. Brusseau Lee Lawrie Treasurer Norlin Boyum, Anne Cowie, Nancy Paul D. Nelson Randall Dana, Cheryl Dickson, Charlton Dietz, Joanne A. Englund, William Frels, 11 Stanford Newel, Proposal Rock, and Newell Park Widows Howard Guthmann, John Holman, Elizabeth Kiernat, Judith Frost Lewis, Rev. Kevin M. Newell Park Celebrates Its Centennial McDonough, Laurie M. Murphy, Richard H. Nichol son, Marla Ordway, Marvin J. Pertzik, Krista Finstad Hanson Jay Pfaender, Ralph Thrane, Richard Wilhoit. Directors Emeriti 20 Growing Up in St. Paul W. -

Office of Dispute Resolution, ODR Approved Mediation Centers, and NMA

Nebraska Office of Dispute Resolution, ODR Approved Mediation Centers, and NMA NE Office of Dispute Resolution Nebraska State Capitol, 12th Floor, 1445 “K” Street P.O. Box 98910 Lincoln, NE 68509; FAX: (402) 471-3071 https://supremecourt.nebraska.gov/programs-services/mediation Debora S. Denny, Director; (402) 471-2766; Email: [email protected] Christina Paulson, Program Analyst; (402) 471-2911; Email: [email protected] Rachel Lempka; Administrative Secretary; (402) 471-3148; Email: [email protected] Central Mediation Center Mediation West 412 W. 48th Street, Suite 22, P.O. Box 838 Office: 210 West 27th Street / Mail: P.O. Box 427 Kearney, NE 68845 Conference Center: 220 W 27th Street TEL (308) 237-4692 and (800) 203-3452 Scottsbluff, NE 69363-0427 FAX (308) 237-5027 TEL (308) 635-2002 and (800) 967-2115 Email: [email protected] FAX (308) 635-2420 www.centralmediationcenter.com www.mediationwest.org Contact: Melissa Gaines Johnson, Executive Director (ext.14) Contact: Charles Lieske, Executive Director Denise Haupt, Office Services Coordinator (ext. 10) [email protected] Paty Reyes-Covalt, Project Coordinator (ext. 11) Kathy Gabrielle-Madelung, Operations Director Farah Greenwald, Program Coordinator (ext. 12) [email protected] Amanda Rodriguez, Family Case Manager (ext. 13) Mary Sheffield, Case Manager Elizabeth Troyer-Miller, Conflict Specialist (ext. 17) [email protected] Mary Rose Richter, RJ Director / PA Mediator George Thackeray, Assistant Case Manager [email protected] -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: VISUALIZING AMERICAN

ABSTRACT Title of Document: VISUALIZING AMERICAN HISTORY AND IDENTITY IN THE ELLEN PHILLIPS SAMUEL MEMORIAL Abby Rebecca Eron, Master of Arts, 2014 Directed By: Professor Renée Ater, Department of Art History and Archaeology In her will, Philadelphia philanthropist Ellen Phillips Samuel designated $500,000 to the Fairmount Park Art Association “for the erection of statuary on the banks of the Schuylkill River … emblematic of the history of America from the time of the earliest settlers to the present.” The initial phase of the resulting sculpture project – the Central Terrace of the Samuel Memorial – should be considered one of the fullest realizations of New Deal sculpture. It in many ways corresponds (conceptually, thematically, and stylistically) with the simultaneously developing art programs of the federal government. Analyzing the Memorial project highlights some of the tensions underlying New Deal public art, such as the difficulties of visualizing American identity and history, as well as the complexities involved in the process of commissioning artwork intended to fulfill certain programmatic purposes while also allowing for a level of individual artists’ creative expression. VISUALIZING AMERICAN HISTORY AND IDENTITY IN THE ELLEN PHILLIPS SAMUEL MEMORIAL By Abby Rebecca Eron Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 Advisory Committee: Professor Renée Ater, Chair Professor Meredith J. Gill Professor Steven A. Mansbach © Copyright by Abby Rebecca Eron 2014 The thesis or dissertation document that follows has had referenced material removed in respect for the owner's copyright. -

Interaction of Aramaeans and Assyrians on the Lower Khabur

Syria Archéologie, art et histoire 86 | 2009 Dossier : Interaction entre Assyriens et Araméens Interaction of Aramaeans and Assyrians on the Lower Khabur Hartmut Kühne Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/syria/509 DOI: 10.4000/syria.509 ISSN: 2076-8435 Publisher IFPO - Institut français du Proche-Orient Printed version Date of publication: 1 November 2009 Number of pages: 43-54 ISBN: 9782351591512 ISSN: 0039-7946 Electronic reference Hartmut Kühne, « Interaction of Aramaeans and Assyrians on the Lower Khabur », Syria [Online], 86 | 2009, Online since 01 July 2016, connection on 22 May 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ syria/509 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/syria.509 © Presses IFPO INTERACTION OF ARAMAEANS AND ASSYRIANS ON THE LOWER KHABUR Hartmut KÜHNE Freie Universität Berlin Résumé – Le modèle centre/périphérie a souvent été utilisé pour expliquer les relations entre Assyriens et Araméens. Il est de plus en plus clair que ce modèle n’est pas apte à rendre compte de l’interaction entre ces deux groupes ethniques. Il convient de se défaire de l’idée de l’influence sur la périphérie et de chercher plutôt les signes des processus d’émulation qui ont lieu entre deux groupes équivalents culturellement et qui s’affrontent dans un territoire sans suprématie politique. Au cours du temps — environ 500 ans, entre 1100 et 600 av. J.-C. —, la situation politique change et avec elle les formes de l’interaction perceptibles au travers des différents traits culturels, illustrés par les objets découverts en fouille. De fait, on doit s’attendre à ce que ces objets reflètent différentes étapes d’émulation et deviennent potentiellement des hybrides, plus ou moins élaborés, ou des transferts plus ou moins profondément modifiés. -

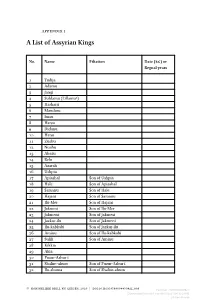

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM Via Free Access 198 Appendix I

Appendix I A List of Assyrian Kings No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 1 Tudija 2 Adamu 3 Jangi 4 Suhlamu (Lillamua) 5 Harharu 6 Mandaru 7 Imsu 8 Harsu 9 Didanu 10 Hanu 11 Zuabu 12 Nuabu 13 Abazu 14 Belu 15 Azarah 16 Ushpia 17 Apiashal Son of Ushpia 18 Hale Son of Apiashal 19 Samanu Son of Hale 20 Hajani Son of Samanu 21 Ilu-Mer Son of Hajani 22 Jakmesi Son of Ilu-Mer 23 Jakmeni Son of Jakmesi 24 Jazkur-ilu Son of Jakmeni 25 Ilu-kabkabi Son of Jazkur-ilu 26 Aminu Son of Ilu-kabkabi 27 Sulili Son of Aminu 28 Kikkia 29 Akia 30 Puzur-Ashur I 31 Shalim-ahum Son of Puzur-Ashur I 32 Ilu-shuma Son of Shalim-ahum © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2020 | doi:10.1163/9789004430921_008 Fei Chen - 9789004430921 Downloaded from Brill.com09/30/2021 04:32:21AM via free access 198 Appendix I No. Name Filiation Date (BC) or Regnal years 33 Erishum I Son of Ilu-shuma 1974–1935 34 Ikunum Son of Erishum I 1934–1921 35 Sargon I Son of Ikunum 1920–1881 36 Puzur-Ashur II Son of Sargon I 1880–1873 37 Naram-Sin Son of Puzur-Ashur II 1872–1829/19 38 Erishum II Son of Naram-Sin 1828/18–1809b 39 Shamshi-Adad I Son of Ilu-kabkabic 1808–1776 40 Ishme-Dagan I Son of Shamshi-Adad I 40 yearsd 41 Ashur-dugul Son of Nobody 6 years 42 Ashur-apla-idi Son of Nobody 43 Nasir-Sin Son of Nobody No more than 44 Sin-namir Son of Nobody 1 year?e 45 Ibqi-Ishtar Son of Nobody 46 Adad-salulu Son of Nobody 47 Adasi Son of Nobody 48 Bel-bani Son of Adasi 10 years 49 Libaja Son of Bel-bani 17 years 50 Sharma-Adad I Son of Libaja 12 years 51 Iptar-Sin Son of Sharma-Adad I 12 years