Value Chain Analysis of Vegetables: the Case of Ejere District, West Shoa Zone, Oromia National Regional State of Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Determinants of Dairy Product Market Participation of the Rural Households

ness & Fi si na u n c B Gemeda et al, J Bus Fin Aff 2018, 7:4 i f a o l l A a Journal of f DOI: 10.4172/2167-0234.1000362 f n a r i r u s o J ISSN: 2167-0234 Business & Financial Affairs Research Article Open Access Determinants of Dairy Product Market Participation of the Rural Households’ The Case of Adaberga District in West Shewa Zone of Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia Dirriba Idahe Gemeda1, Fikiru Temesgen Geleta2 and Solomon Amsalu Gesese3 1Department of Agricultural Economics, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, Ambo University, Ethiopia 2Department of Agribusiness and Value Chain Management, College of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences, Ambo University, Ethiopia Abstract Ethiopia is believed to have the largest Livestock population in Africa. Dairy has been identified as a priority area for the Ethiopian government, which aims to increase Ethiopian milk production at an average annual growth rate of 15.5% during the GTP II period (2015-2020), from 5,304 million litters to 9,418 million litters. This study was carried out to assess determinants of dairy product market participation of the rural households in the case of Adaberga district in West Shewa zone of Oromia national regional state, Ethiopia. The study took a random sample of 120 dairy producer households by using multi-stage sampling procedure and employing a probability proportional to sample size sampling technique. For the individual producer, the decision to participate or not to participate in dairy production was formulated as binary choice probit model to identify factors that determine dairy product market participation. -

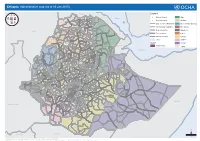

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (August 2017)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (August 2017) ERITREA National capital P Erob Tahtay Adiyabo Regional capital Gulomekeda Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Ahferom Red Sea Humera Adigrat ! ! Dalul ! Adwa Ganta Afeshum Aksum Saesie Tsaedaemba Shire Indasilase ! Zonal Capital ! North West TigrayTahtay KoraroTahtay Maychew Eastern Tigray Kafta Humera Laelay Maychew Werei Leke TIGRAY Asgede Tsimbila Central Tigray Hawzen Medebay Zana Koneba Naeder Adet Berahile Region boundary Atsbi Wenberta Western Tigray Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele Zone boundary Tanqua Abergele P Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Tsegede Tselemt Mekele Town Special Enderta Afdera Addi Arekay South East Ab Ala Tsegede Mirab Armacho Beyeda Woreda boundary Debark Erebti SUDAN Hintalo Wejirat Saharti Samre Tach Armacho Abergele Sanja ! Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Addis Ababa Ziquala Maychew ! Wegera Metema Lay Armacho Wag Himra Endamehoni Raya Azebo North Gondar Gonder ! Sekota Teru Afar Chilga Southern Tigray Gonder City Adm. Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Gaz Gibla Zone 4 (Fantana Rasu ) Elidar Amhara Gelegu Quara ! Takusa Ebenat Gulina Bugna Awra Libo Kemkem Kobo Gidan Lasta Benishangul Gumuz North Wello AFAR Alfa Zone 1(Awsi Rasu) Debre Tabor Ewa ! Fogera Farta Lay Gayint Semera Meket Guba Lafto DPubti DJIBOUTI Jawi South Gondar Dire Dawa Semen Achefer East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Delanta Habru Asayita P Tach Gayint ! Bahir Dar City Adm. Aysaita Guba AMHARA Dera Ambasel Debub Achefer Bahirdar Zuria Dawunt Worebabu Gambela Dangura West Esite Gulf of Aden Mecha Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Simada Thehulederie Kutaber Dangila Yilmana Densa Afambo Mekdela Tenta Awi Dessie Bati Hulet Ej Enese ! Hareri Sayint Dessie City Adm. -

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1. Tigrey No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Adwa 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 2(*) Hawzen 12 3(*) Wukro 7 Per Feasibility Study 4(*) Samre 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Alamata 10 Total 55 1 Tahtay Adiyabo 8 2 Medebay Zana 10 3 Laelay Mayechew 10 4 Kola Temben 11 5 Abergele 7 Per Filed Survey by ETC 6 Ganta Afeshum 15 7 Atsbi Wenberta 9 8 Enderta 14 9(*) Hintalo Wajirat 16 10 Ofla 15 Total 115 1 Kafta Humer 5 2 Laelay Adiyabo 8 3 Tahtay Koraro 8 4 Asegede Tsimbela 10 5 Tselemti 7 6(**) Welkait 7 7(**) Tsegede 6 8 Mereb Lehe 10 9(*) Enticho 21 10(**) Werie Lehe 16 Per Filed Survey by ETC 11 Tahtay Maychew 8 12(*)(**) Naeder Adet 9 13 Degua temben 9 14 Gulomahda 11 15 Erob 10 16 Saesi Tsaedaemba 14 17 Alage 13 18 Endmehoni 9 19(**) Rayaazebo 12 20 Ahferom 15 Total 208 1/14 Tigrey D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 2. Affar No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Ayisaita 3 2 Dubti 5 Per Filed Survey by ETC 3 Chifra 2 Total 10 1(*) Mile 1 2(*) Elidar 1 3 Koneba 4 4 Berahle 4 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Amibara 5 6 Gewane 1 7 Ewa 1 8 Dewele 1 Total 18 1 Ere Bti 1 2 Abala 2 3 Megale 1 4 Dalul 4 5 Afdera 1 6 Awash Fentale 3 7 Dulecha 1 8 Bure Mudaytu 1 Per Filed Survey by ETC 9 Arboba Special Woreda 1 10 Aura 1 11 Teru 1 12 Yalo 1 13 Gulina 1 14 Telalak 1 15 Simurobi 1 Total 21 2/14 Affar D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 3. -

Determinants of Smallholder Farmers' Decision to Adopt Adaptation

Amare and Simane Agric & Food Secur (2017) 6:64 DOI 10.1186/s40066-017-0144-2 Agriculture & Food Security RESEARCH Open Access Determinants of smallholder farmers’ decision to adopt adaptation options to climate change and variability in the Muger Sub basin of the Upper Blue Nile basin of Ethiopia Abayineh Amare* and Belay Simane Abstract Smallholder farmers’ decisions to adopt adaptation options in response to climate change and variability are infu- enced by socioeconomic, institutional, and environmental factors, indicating that decision patterns can be very specifc to a given locality. The prime objective of this research is to identify factors afecting smallholder farmers’ decisions to adopt adaptation options to climate change and variability in the Muger River sub-basin of the Blue Nile basin of Ethiopia. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected using a semi-structured questionnaire, focused group discussions, and key informant interviews from 442 sampled households. Frequency, mean, Chi-square test, and one-way ANOVA were used for analysis. Furthermore, a multinomial logit model was employed to analyze the data. Results signifed that small-scale irrigation, agronomic practices, livelihood diversifcation, and soil and water conservation measures are the dominant adaptation options that smallholder farmers used to limit the negative impact of climate change and variability in the study area. The results further revealed that adoption of small-scale irrigation as an adaptation to climate change and variability is signifcantly and positively infuenced by access to credit, social capital, and the educational status of household heads. Greater distance to marketplace and size of farmland negatively afected the use of agronomic practices, whereas crop failure experience and access to early warning systems have a positive infuence. -

Evidence from Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile, Ethiopia Abayineh Amare* and Belay Simane

Amare and Simane Ecological Processes (2018) 7:13 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-018-0124-x RESEARCH Open Access Does adaptation to climate change and variability provide household food security? Evidence from Muger sub-basin of the upper Blue-Nile, Ethiopia Abayineh Amare* and Belay Simane Abstract Introduction: The purpose of this study is to evaluate the associated impact of adoption of adaptation options to climate change and variability on household food security in the Muger sub-basin of the upper Blue-Nile of Ethiopia using a comprehensive data of 442 sampled households from four representative districts’ in the sub-basin. The study used a propensity score matching approach to evaluate the impact of adaptation options on household food security. Results: Results show that the decision to adopt adaptation options is found to be positively influenced by male household heads, family size, access to extension service, the size of landholding, and frequency of drought and floods over the past many years. The results further reveal that farmers adopting any of the adaptation options had higher food calorie intake per day per adult equivalent than those who did not. Conclusions: A policy that promotes the adoption of soil and water conservation measures, small-scale irrigation, agronomic practices, and livelihood diversification strategies should be central to food security strategy in the study area. Keywords: Food security, Impact, Adaptation, Climate change, Muger sub-basin Introduction A large body of literature has recognized adaptation as The impact of climate change on food security in Sub- one of the policy options in response to climate change Saharan Africa have largely been explored by a plethora impact (Smit et al. -

Ethiopia: Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ERITREA Legend Ahferom Erob ^! Tahtay Adiyabo National Capital Gulomekeda Afar Laelay Adiyabo Mereb Leke Red Sea Dalul Ganta Afeshum P! Adwa SaesEiea Tsatedranemba Regional Capital Amhara North WesternTahtay KoraroLaelay Maychew Kafta Humera Tahtay Maychew Werei Leke Hawzen Asgede Tsimbila Central Koneba TIGRAY Medebay Zana Naeder Adet Berahile Western Atsbi Wenberta Undetermined boundary Beneshangul Gumuz Kelete Awelallo Welkait Kola Temben Tselemti Degua Temben Mekele P! Zone 2 International boundary Dire Dawa Tsegede Tselemt Enderta Tanqua Abergele Afdera Addi Arekay Ab Ala Tsegede Beyeda Mirab Armacho Afdera Region boundary Gambela Debark Saharti Samre Erebti Hintalo Wejirat SUDAN Abergele Tach Armacho Dabat Janamora Megale Bidu Alaje Sahla Southern Zone boundary Hareri Ziquala Raya Azebo Metema Lay Armacho Wegera Wag Himra Endamehoni North Gonder Sekota Teru Chilga Woreda boundary Oromia Yalo East Belesa Ofla West Belesa Kurri Dehana Dembia Gonder Zuria Alamata Zone 4 Elidar Gaz Gibla Lake SNNPR Quara Takusa Ebenat Gulina Libo Kemkem Bugna Awra Kobo Tana Gidan Region Lasta (Ayna) AFAR Somali Alfa Ewa Fogera Farta North Wollo Semera Lay Gayint Meket Guba Lafto P! Dubti Zone 1 DJIBOUTI Addis Ababa Jawi Semen Achefer South Gonder Tigray East Esite Chifra Bahir Dar Wadla Habru Aysaita AMHARA P! Dera Tach Gayint Delanta Guba Bahirdar Zuria Ambasel Debub Achefer Dawunt Worebabu Dangura Gulf of Aden Mecha West Esite Simada Thehulederie Adaa'r Mile Pawe Special Afambo Dangila Kutaber Yilmana -

Total Needy Population, Humanitarain Requirement February-June 2013

Total Needy Population, Humanitarain Requirement February-June 2013 GulomekedaErob Tahtay Adiyabo Mereb LekeAhferom Laelay Adiyabo Ganta Afeshum Dalul Legend Adwa Saesie Tsaedaemba Werei Leke · Tigray HawzenKoneba Lakes Asgede Tsimbila Naeder Adet Atsbi Wenberta Berahle Kola Temben Kelete Awelallo Tselemti Degua Temben Administrative boundary Tselemt Tanqua Abergele Enderta Ab Ala Afdera Region Saharti Samre Hintalo Wejirat Erebti Abergele Megale Bidu Sahla Alaje Ziquala Zone Wegera Endamehoni Sekota Raya Azebo Teru East Belesa Ofla Yalo Woreda Dehana Kurri Gaz Gibla Alamata Elidar Ebenat Gulina Awra Total needy population Lasta (Ayna)Gidan Kobo Afar Meket Guba Lafto Dubti 0 (No requirment) Delanta Habru Chifra Aysaita Ambasel Guba Amhara Worebabu 242 - 9478 Pawe Special Adaa'r Mile MekdelaTenta Afambo z Bati u Sayint Kalu Telalak 9689 - 19397 m u Legambo Dewa HarewaDewe G Artuma Fursi l Kelela 19960 - 31139 Kurmuk u Gishe Rabel Artuma g Gewane n Menz Gera Midir a FursiBure Mudaytu h Dera Eferatana Gidem 39572 - 71693 is Menz Mama Midir Assosa n Gida Kiremu Wara JarsoHidabu Abote Kewet e Jarte Jardega Dembel DegemGerar Jarso Simurobi Gele'alo 116968 B Abuna G/BeretKuyu Tarema Ber Dire Dawa Teferi Ber Bambasi Abichuna Gne'a Ginde Beret Yaya Gulele Chinaksen Wuchale AnkoberDulechaAmibara Dire DawaJarso Meta Robi Jida Goro Gutu Jeldu Adda Berga KembibitArgoba Special KersaHaro Maya Jijiga Doba Meta Gursum Aleltu Deder Harar Sasiga Ifata Mieso Tulo Gawo Kebe Awash Fentale Chiro Zuria Jimma Horo Diga MeselaBedeno Goba Koricha Hareri Dale Sadi -

Prevalence of Bacterial Wilt of Ginger (Z

International Journal of Research Studies in Agricultural Sciences (IJRSAS) Volume 1, Issue 6, 2015, PP 14-22 ISSN 2454–6224 www.arcjournals.org Prevalence of Bacterial Wilt of Ginger (Z. Officinale) Caused by Ralstonia Solansearum (Smith) in Ethiopia Habetewold kifelew1, Bekelle Kassa2, Kasahun Sadessa3, Tariku Hunduma3 1Tepi National Spice Research Center, Tepi, SNNPRS, Ethiopia 2Holetta Agricultural Research Center 3Ambo Plant Protection Research Center [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: Ginger is one of the most important spices, largely for small scale farmer in Ethiopia. In many production areas of Ethiopia up to 85% of the farmers and 35% of the total arable land were allotted for ginger production. However, this potential spices crop wiped out by a sudden outbreak of bacterial wilt epidemics in 2011 and 2012. A survey was conducted on the status of ginger bacterial wilt incidence in major growing areas of Ethiopia and laboratory work was done to identify the causal agent of ginger wilt. The diseases were found distributed in all ginger growing areas and the loss were estimated up to 100%. During 2012 survey season the wilt incidence percentage was recorded maximum (93.5) in Sheka zone followed by Benchmaji zone (91.6) and Majang zone (65.7) while the lowest wilt incidence was recorded in gamogofa zone (10.7). During 2014 survey season wilt incidence percentage was recorded maximum (98.9) in Benchmaji zone followed by Majang zone (98.8) and Sheka zone (97.4) while the lowest wilt incidence was recorded in Keffa zone (78.4). The syptomology and pathogenicity test confirmed the bacteria were R. -

Climate Change Induced Vulnerability of Smallholder Farmers: Agroecology-Based Analysis in the Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of Ethiopia

American Journal of Climate Change, 2017, 6, 668-693 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ajcc ISSN Online: 2167-9509 ISSN Print: 2167-9495 Climate Change Induced Vulnerability of Smallholder Farmers: Agroecology-Based Analysis in the Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of Ethiopia Abayineh Amare*, Belay Simane College of Development Studies, Centre for Environment and Development, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia How to cite this paper: Amare, A. and Abstract Simane, B. (2017) Climate Change Induced Vulnerability of Smallholder Farmers: Ethiopia is also frequently identified as a country that is highly vulnerable to Agroecology-Based Analysis in the Muger climate variability and change. The potential adverse effects of climate change Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of on Ethiopia’s agricultural sector are a major concern, particularly given the Ethiopia. American Journal of Climate Change, 6, 668-693. country’s dependence on agricultural production, which is sensitive to climate https://doi.org/10.4236/ajcc.2017.64034 change and variability. This problem calls the need to understand agroecology based vulnerability to climate change and variability to better adapt to climate Received: October 9, 2017 risks and promote strategies for local communities so as to enhance food se- Accepted: December 16, 2017 Published: December 19, 2017 curity. The objective of this study is to estimate and compare the level of vul- nerability of smallholder farmers’ to climate change and variability from three Copyright © 2017 by authors and agroecology representing Muger River sub-Basin of the upper Blue Nile basin Scientific Research Publishing Inc. using Livelihood Vulnerability Index. -

Evidence from Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of Ethiopia

Linking Vulnerability, Adaptation and Food Security in a Changing Climate: Evidence from Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of Ethiopia Abayineh Amare A Dissertation Submitted to Center for Environment and Development Studies, College of Development Studies Presented in the Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Development Studies (Environment and Development Studies) Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2018 Linking Vulnerability, Adaptation and Food Security in a Changing Climate: Evidence from Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of Ethiopia Abayineh Amare A Dissertation Submitted to Center for Environment and Development Studies, College of Development Studies Presented in the Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Development Studies (Environment and Development Studies) Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2018 i Declaration I, the undersigned, declare that this is my original work, has never been presented in this or any other University, and that all the resources and materials used for the dissertation, have been fully acknowledged. Name:-__Abayineh Amare Signature: Date: - June 05, 2018 Place: - Addis Ababa Date of submission June 05, 2018 This dissertation has been submitted for examination with my approval as University supervisor. Supervisor name: - Belay Simane (PhD.) Signature: Date: - June 05, 2018 ii iii iv Linking Vulnerability, Adaptation and Food Security in a Changing Climate: Evidence from Muger Sub-Basin of the Upper Blue-Nile Basin of Ethiopia ABSTRACT Ethiopia has been deemed a climate ‘hot-spot’- a place where a changing climate pose grave threats to agricultural production, food security and human well-being. -

Prevalence of and Risk Factors For

Ophthalmic Epidemiology ISSN: 0928-6586 (Print) 1744-5086 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iope20 Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia: Results of 79 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Conducted with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project Berhanu Bero, Colin Macleod, Wondu Alemayehu, Solomon Gadisa, Ahmed Abajobir, Yilikal Adamu, Menbere Alemu, Liknaw Adamu, Michael Dejene, Addis Mekasha, Zelalem Habtamu Jemal, Damtew Yadeta, Oumer Shafi, Genet Kiflu, Rebecca Willis, Rebecca M. Flueckiger, Brian K. Chu, Alexandre L. Pavluck, Anthony W. Solomon & for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project To cite this article: Berhanu Bero, Colin Macleod, Wondu Alemayehu, Solomon Gadisa, Ahmed Abajobir, Yilikal Adamu, Menbere Alemu, Liknaw Adamu, Michael Dejene, Addis Mekasha, Zelalem Habtamu Jemal, Damtew Yadeta, Oumer Shafi, Genet Kiflu, Rebecca Willis, Rebecca M. Flueckiger, Brian K. Chu, Alexandre L. Pavluck, Anthony W. Solomon & for the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (2016) Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia: Results of 79 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Conducted with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Ophthalmic Epidemiology, 23:6, 392-405, DOI: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1243717 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2016.1243717 © 2016 The Authors. Published with license Published online: 07 Nov 2016. by Taylor & Francis Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2068 View Crossmark data Citing articles: 19