Application of Eugene Nida's Theory of Translation to the English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And How to Convert to Islam in the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious

What is Islam? and How to Convert to Islam In the Name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful All Praise be to Allah, the Lord of the Worlds and may peace and blessings of Allah be upon the most honorable of all Prophets and Messengers; Muhammad. Introduction Every right or wrong ideology, every beneficial or harmful community association and every good or evil party has principles, intellectual basis and ideological issues that determine its purpose and direction and become as a constitution for its members and followers. Whoever wants to belong to one of them, has to look firstly at its principles. If he is satisfied with the principles, believes of its validity and accepts it with his conscious and subconscious mind without any doubts, then he can be a member of that association or party. Afterwards, he enrolls among the lines of its members and has to perform the duties required by the constitution and pay the membership fees that are set by the laws. He also has to exhibit behaviors indicate loyalty to its principles besides always remembering those principles to not commit deeds contradict with them. He has to be a perfect example via showing decent morals and behaviors and become a real proponent of them. Nutshell, being a member of a party or association requires: knowing its laws, believing in itsprinciples, obeying its rules and conducing one’s life accordance to it.This is a general situation that also applies to Islam. Therefore, whoever wants to enter Islam has to firstly accept its rational bases and assertively believe in them in order to have strong doctrine or faith. -

An Analysis of Taqwa in the Holy Quran: Surah Al- Baqarah

IJASOS- International E-Journal of Advances in Social Sciences, Vol. III, Issue 8, August 2017 AN ANALYSIS OF TAQWA IN THE HOLY QURAN: SURAH AL- BAQARAH Harison Mohd. Sidek1*, Sulaiman Ismail2, Noor Saazai Mat Said3, Fariza Puteh Behak4, Hazleena Baharun5, Sulhah Ramli6, Mohd Aizuddin Abd Aziz7, Noor Azizi Ismail8, Suraini Mat Ali9 1Associate Professor Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 2Mr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 3Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 4 Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 5 Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 6 Ms., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 7 Mr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 8Associate Professor Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] 9Dr., Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia, MALAYSIA, [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract Within the context of the Islamic religion, having Taqwa or the traits of righteousness is imperative because Taqwa reflects the level of a Muslim’s faith. Hence, the purpose of the present study was to identify the traits of Takwa in surah Al-Baqara in the Holy Quran. The data for this study were obtained from verses in surah Al-Baqara. Purposive sampling was used to select the verses that contain the traits of Taqwa using an established tafseer (Quranic interpretation) in the Qurainic field as a guideline in marking the Taqwa traits in sampling the verses. Two experts in the field of Quranic tafseer validated the traits of Taqwa extracted from each selected verse. -

Translation: an Advanced Resource Book

TRANSLATION Routledge Applied Linguistics is a series of comprehensive resource books, providing students and researchers with the support they need for advanced study in the core areas of English language and Applied Linguistics. Each book in the series guides readers through three main sections, enabling them to explore and develop major themes within the discipline: • Section A, Introduction, establishes the key terms and concepts and extends readers’ techniques of analysis through practical application. • Section B, Extension, brings together influential articles, sets them in context, and discusses their contribution to the field. • Section C, Exploration, builds on knowledge gained in the first two sections, setting thoughtful tasks around further illustrative material. This enables readers to engage more actively with the subject matter and encourages them to develop their own research responses. Throughout the book, topics are revisited, extended, interwoven and deconstructed, with the reader’s understanding strengthened by tasks and follow-up questions. Translation: • examines the theory and practice of translation from a variety of linguistic and cultural angles, including semantics, equivalence, functional linguistics, corpus and cognitive linguistics, text and discourse analysis, gender studies and post- colonialism • draws on a wide range of languages, including French, Spanish, German, Russian and Arabic • explores material from a variety of sources, such as the Internet, advertisements, religious texts, literary and technical texts • gathers together influential readings from the key names in the discipline, including James S. Holmes, George Steiner, Jean-Paul Vinay and Jean Darbelnet, Eugene Nida, Werner Koller and Ernst-August Gutt. Written by experienced teachers and researchers in the field, Translation is an essential resource for students and researchers of English language and Applied Linguistics as well as Translation Studies. -

Dramatizing the Sura of Joseph: an Introduction to the Islamic Humanities

Dramatizing the Sura of Joseph: An introduction to the Islamic humanities Author: James Winston Morris Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/4235 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Published in Journal of Turkish Studies, vol. 18, pp. 201-224, 1994 Use of this resource is governed by the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons "Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States" (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/) Dramatizing the Sura ofJoseph: An Introduction to the Islamic Humanities. In Annemarie Schimmel Festschrift, special issue of Journal of Turkish Studies (H8lVard), vol. 18 (1994), pp. 20\·224. Dramatizing the Sura of Joseph: An Introduction to the Islamic Humanities. In Annemarie Schimmel Festschrift, special issue of Journal of Turkish Studies (Harvard), vol. 18 (1994), pp. 201-224. DRAMATIZING THE SURA OF JOSEPH: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE ISLAMIC HUMANITIES James W. Morris J "Surely We are recounting 10 you the most good-and-beautiful of laJes ...." (Qur'an. 12:3) Certainly no other scholar ofher generation has dooe mae than Annemarie Schimmel to ilIwninal.e the key role of the Islamic hwnanities over the centuries in communicating and bringing alive for Muslims the inner meaning of the Quru and hadilh in 30 many diverse languages and cultural settings. Long before a concern with '"populal'," oral and ve:macul.- religious cultures (including tKe lives of Muslim women) had become so fashK:inable in religious and bi.storica1 studies. Professor Scbimmel's anicJes and books were illuminating the ongoing crutive expressions and transfonnalions fA Islamic perspectives in both written and orallilrnblr'es., as well as the visual ar:1S, in ways tba have only lllCentIy begun 10 make their war into wider scholarly and popular understandings of the religion of Islam. -

The Jihadi Threat: ISIS, Al-Qaeda, and Beyond

THE JIHADI THREAT ISIS, AL QAEDA, AND BEYOND The Jihadi Threat ISIS, al- Qaeda, and Beyond Robin Wright William McCants United States Institute of Peace Brookings Institution Woodrow Wilson Center Garrett Nada J. M. Berger United States Institute of Peace International Centre for Counter- Terrorism Jacob Olidort The Hague Washington Institute for Near East Policy William Braniff Alexander Thurston START Consortium, University of Mary land Georgetown University Cole Bunzel Clinton Watts Prince ton University Foreign Policy Research Institute Daniel Byman Frederic Wehrey Brookings Institution and Georgetown University Car ne gie Endowment for International Peace Jennifer Cafarella Craig Whiteside Institute for the Study of War Naval War College Harleen Gambhir Graeme Wood Institute for the Study of War Yale University Daveed Gartenstein- Ross Aaron Y. Zelin Foundation for the Defense of Democracies Washington Institute for Near East Policy Hassan Hassan Katherine Zimmerman Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy American Enterprise Institute Charles Lister Middle East Institute Making Peace Possible December 2016/January 2017 CONTENTS Source: Image by Peter Hermes Furian, www . iStockphoto. com. The West failed to predict the emergence of al- Qaeda in new forms across the Middle East and North Africa. It was blindsided by the ISIS sweep across Syria and Iraq, which at least temporarily changed the map of the Middle East. Both movements have skillfully continued to evolve and proliferate— and surprise. What’s next? Twenty experts from think tanks and universities across the United States explore the world’s deadliest movements, their strate- gies, the future scenarios, and policy considerations. This report reflects their analy sis and diverse views. -

Dynamic Equivalence: Nida's Perspective and Beyond

Dynamic Equivalence: Nida’s Perspective and Beyond Dohun Kim Translation is an interlingual and intercultural communication, in which correspondence at the level of formal and meaningful structures does not necessarily lead to a successful communication: a secondary communication or even a communication breakdown may occur due to distinct historical-cultural contexts. Such recognition led Nida to put forward Dynamic Equivalence, which brings the receptor to the centre of the communication. The concept triggered the focus shift from the form of the message to the response of the receptor. Further, its theoretical basis went beyond applying the research results of linguistics to the practice of translation; it founded a linguistic theory of translation for researchers and provided a practical manual of translation for translators. While Nida’s claims on the priority of Dynamic Equivalence over Formal Correspondence have been widely accepted and cited by translation researchers and practitioners, the mechanism and validity of Nida’s theoretical construct of the translation process have been neither addressed nor updated sufficiently. Hence, this paper sets out to revisit Nida and explain in detail what his theoretical background was, and how it led him to Formal Correspondence and Dynamic Equivalence. Keywords: deep structure, dynamic equivalence, kernel, receptor response, translation model We must analyze the transmission of a message in terms of a dynamic dimension. This analysis is especially important for translating, since the production -

Surah & Verses Facts

Surah & Verses Facts Verses Recited: 1 - al-Faatihah – ‘The Opening’, 2 - Baqarah – ‘The Cow’ (Verses 1-141) Objective: Al-Baqarah’s main objective is the succession of man on earth. To put it simply, it calls upon us, “You Muslims are responsible for earth”. Other Facts: Al-Baqarah is the first surah to be revealed in Al-Madinah after the Prophet’s emigration - Surat Al-Baqara is the longest surah in the Qur’an comprising of 286 ayahs Surah 1 - al-Faatihah –‘ The Opening Summary: It is named al-Faatihah, the Opening - because it opens the Book and by it the recitation in prayer commences. It is also named Ummul Qur`aan, the Mother of the Qur`aan, and Ummul Kitaab, the Mother of the Book. In essence it is the supplication to which what follows from the Quran is the response. Surah 2 - Baqarah –‘The Cow’ Summary: This is the longest Surah of the Quran, and in it occurs the longest verse (2:282). The name of the Surah is from the Parable of the Cow (2:67-71), which illustrates the insufficiency of quarrelsome obedience. When faith is lost, people put off obedience with various excuses; even when at last they obey in the letter, they fail in the spirit and this prevents them from seeing that spiritually they are not alive but dead. For life is movement, activity, striving, fighting against baser things. And this is the burden of the Surah. Verses Description The surah begins by classifying men into three broad categories, depending on how they receive God’s 2:1-29 message 2:30-39 The story of the creation of man, the high destiny intended for him, his fall, and the hope held out to him The story of the children of Israel is told according to their own traditions – what privileges they received and 2:40-86 how they abused them thus illustrating again as a parable the general story of man. -

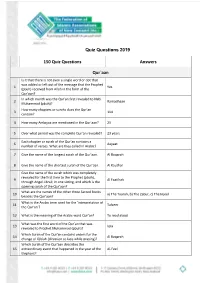

Quiz Questions 2019

Quiz Questions 2019 150 Quiz Questions Answers Qur`aan Is it that there is not even a single word or dot that was added or left out of the message that the Prophet 1 Yes (pbuh) received from Allah in the form of the Qur’aan? In which month was the Qur’an first revealed to Nabi 2 Ramadhaan Muhammad (pbuh)? How many chapters or surahs does the Qur’an 3 114 contain? 4 How many Ambiyaa are mentioned in the Qur’aan? 25 5 Over what period was the complete Qur’an revealed? 23 years Each chapter or surah of the Qur’an contains a 6 Aayaat number of verses. What are they called in Arabic? 7 Give the name of the longest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Baqarah 8 Give the name of the shortest surah of the Qur’aan. Al Kauthar Give the name of the surah which was completely revealed for the first time to the Prophet (pbuh), 9 Al Faatihah through Angel Jibrail, in one sitting, and which is the opening surah of the Qur’aan? What are the names of the other three Sacred Books 10 a) The Taurah, b) The Zabur, c) The Injeel besides the Qur’aan? What is the Arabic term used for the ‘interpretation of 11 Tafseer the Qur’an’? 12 What is the meaning of the Arabic word Qur’an? To read aloud What was the first word of the Qur’an that was 13 Iqra revealed to Prophet Muhammad (pbuh)? Which Surah of the Qur’an contains orders for the 14 Al Baqarah change of Qiblah (direction to face while praying)? Which Surah of the Qur’aan describes the 15 extraordinary event that happened in the year of the Al-Feel Elephant? 16 Which surah of the Qur’aan is named after a woman? Maryam -

The Concept of Jihad in Islam

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 9, Ver. 7 (Sep. 2016) PP 35-42 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Concept of Jihad In Islam Ramlan TengkuErwinsyahbana Nurul Hakim Abstract.:-It is an undisputable fact that jihad is an Islamic teaching that is explicitly mentioned in Quran, Hadith, ijma'as well as various fiqh literature from classical time to the contemporary time. Jihad term often used for things that are destructive by western scholars and society. For them, jihad is synonymous with terrorism. The similarization of the word Jihad with the word terrorism in the Western perception is strongly reinforced by a series of terror committed by Muslims in the name of jihad. These acts have been increasingly affecting the interpretation of the word jihad in a negative way although in reality that is not the case in a contemporary context. Jihad in contemporary understanding is not just a war against visible enemies but also a war against the devil and carnality. Even a war against visible enemies that are written in classical fiqh books has now replaced by a contemporary interpretation of jihad against the enemies, as was done by Dr. ZakirNaik. KEYWORDS:Concept, Jihad and Islam I. INTRODUCTION When the 9/11 attack hit the United States more than a decade ago, the term jihad became a trending topic worldwide. The US and other Western countries in general claim that the perpetrators of the 9/11 attack were following the doctrine of Jihad in Islam in order to fight against America and its allies around the world. -

“The Dynamic Equivalence Caper”—A Response

Wendland and Pattemore, “Dynamic,” OTE 26 (2013): 471-490 471 “The Dynamic Equivalence Caper”—A Response ERNST WENDLAND (S TELLEBOSCH UNIVERSITY ) AND STEPHEN PATTEMORE (U NITED BIBLE SOCIETIES ) ABSTRACT This article overviews and responds to Roland Boer’s recent wide- ranging critique of Eugene A Nida’s theory and practice of “dynamic equivalence” in Bible translating. 1 Boer’s narrowly- focused, rather insufficiently-researched evaluation of Nida’s work suffers from both a lack of historical perspective and a current awareness of what many, more recent translation scholars and practitioners have been writing for the past several decades. Our rejoinder discusses some of the major misperceptions and mislead- ing assertions that appear sequentially in the various sections of Boer’s article with the aim of setting the record straight, or at least of framing the assessment of modern Bible translation endeavors and goals in a more positive and accurate light. A INTRODUCTION: A “CAPER”? Why does Boer classify the dynamic equivalence (DE) approach as a “caper”? According to the Oxford Dictionary, a “caper” refers to (1) “a playful skipping 1 Roland Boer, “The Dynamic Equivalence Caper,” in Ideology, Culture, and Translation (ed. Scott S. Elliott and Roland Boer; Atlanta: Society of Biblical Litera- ture, 2012), 13-23. Boer’s article introduces and potentially negatively colors the collection of essays in which it appears, most of which derive from several meetings of the “Ideology, Culture, and Translation” group of the SBL, from 2005 to the pre- sent (Boer, “Dynamic Equivalence,” 1, 4). After a short introduction by the editors, two larger sections follow—the first more theoretical (“Exploring the Intersection of Translation Studies and Critical Theory in Biblical Studies”), the second dealing with a number of case studies (“Sites in Translation”). -

Bible Translation in the UBS

128 성경원문연구 제14호 Bible Translation in the UBS By Aloo Osotsi Mojola* I. Introducing the Nida & Post Nida Perspectives: Third Presentation Introduction: Bible Translation in the UBS in the 20th Century was characterized by the Nida perspective. Eric M. North's brilliant appreciation of Eugene Nida's life and contributions written to mark his 60th birthday in 1974 is good place to begin. (See Matthew Black and William Smalley, eds. On Language, Culture and Religion In Honor of Eugene A. Nida, The Hague: Mouton, 1974: vii-xxvii). Nida's interest, labours and contribution to Bible translation began in the late 1930's and continue to this day albeit in a limited way. Nonetheless his writings and ideas dominated the field for the rest of the century. We are all to various extents indebted to him. 1. Just to name a few, Eugene Nida's key contributions to our field: a) He was trail blazer and pioneer through the medium of his ground breaking books, eg. Bible Translating, ABS, 1947 & Toward and Science of Translating E. J. Brill, 1964, The Theory and Practice of Translating (with Charles Taber), E. J. Brill, 1969 (Translation Studies), * United Bible Societies, Nairobi, Kenya. Presentation to be given at the Korean Translation Workship in Seoul, Korea, February 2003. Bible Translation in the UBS / Aloo Osotsi Mojola 129 Customs and Cultures, Harper & Row, 1954 (Cross Cultural Studies), Message and Mission, Harper & Row, 1960 (Communication Studies), Componential Analysis of Meaning, Mouton, 1975 & Greek Dictionary based on Semantic Domains (with Johannes Louw) (Semantics and Lexicography), etc. b) He pioneered through his global travels and field visits to translation teams in remote locations world wide much of what UBS translation consultants are still doing today. -

Dynamic Equivalence and Formal Equivalence

Unit One Linguistic Approaches to Translation Unit One Linguistic Approaches to Translation Chapter 1 Eugene Nida Dynamic Equivalence and Formal Equivalence Chapter 2 Peter Newmark Semantic and Communicative Translation Chapter 3 Albrecht Neubert Translation as Text ~~ U1-U2.indd 1 2009.9.9 5:33:11 PM Selected Readings of Contemporary Western Translation Theories Introduction Translation was not investigated scientifically until the 1960s in the Western history of translation as a great number of scholars and translators believed that translation was an art or a skill. When the American linguist and translation theorist E. A. Nida was working on his Toward a Science of Translating (1964), he argued that the process of translation could be described in an objective and scientific manner, “for just as linguistics may be classified as a descriptive science, so the transference of a message from one language to another is likewise a valid subject for scientific description” (1964:3). Hence Nida in his work makes full use of the new development of linguistics, semantics, information theory, communication theory and sociosemiotics in an attempt to explore the various linguistic and cultural factors involved in the process of translating. For instance, when discussing the process of translation, Nida adopts the useful elements of the transformational generative grammar put forward by the American linguist Noam Chomsky, suggesting that it is more effective to transfer the meaning from the source language to the receptor language on the kernel level, a key concept in Chomsky’s theory. Nida’s theory of dynamic equivalence, which is introduced in this unit, also approaches translation from a sociolinguistic perspective.