SCOPYRIGHT This Copy Has Been Supplied by the Library of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storm in a Pee Cup Drug-Related Impairment in the Workplace Is Undoubtedly a Serious Issue and a Legitimate Concern for Employers

Mattersof Substance. august 2012 Volume 22 Issue No.3 www.drugfoundation.org.nz Storm in a pee cup Drug-related impairment in the workplace is undoubtedly a serious issue and a legitimate concern for employers. But do our current testing procedures sufficiently balance the need for accuracy, the rights of employees and the principles of natural justice? Or does New Zealand currently have a drug testing problem? CONTENTS ABOUT A DRUG Storm in 16 COVER STORY FEATURE a pee cup STORY CoveR: More than a passing problem 06 32 You’ve passed your urine, but will you pass your workplace drug test? What will the results say about your drug use and level of impairment? Feature ARTICLE OPINION NZ 22 28 NEWS 02 FEATURES Become 14 22 26 30 a member Bizarre behaviour Recovery ruffling Don’t hesitate A slug of the drug Sensible, balanced feathers across the Just how much trouble can What’s to be done about The NZ Drug Foundation has been at reporting and police work Tasman you get into if you’ve been caffeine and alcohol mixed the heart of major alcohol and other reveal bath salts are Agencies around the world taking drugs, someone beverages, the popular drug policy debates for over 20 years. turning citizens into crazy, are newly abuzz about overdoses and you call poly-drug choice of the During that time, we have demonstrated violent zombies! recovery. But do we all 111? recently post-pubescent? a strong commitment to advocating mean the same thing, and policies and practices based on the best does it matter? evidence available. -

The Politics of Post-War Consumer Culture

New Zealand Journal of History, 40, 2 (2006) The Politics of Post-War Consumer Culture THE 1940s ARE INTERESTING YEARS in the story of New Zealand’s consumer culture. The realities of working and spending, and the promulgation of ideals and moralities around consumer behaviour, were closely related to the political process. Labour had come to power in 1935 promising to alleviate the hardship of the depression years and improve the standard of living of all New Zealanders. World War II intervened, replacing the image of increasing prosperity with one of sacrifice. In the shadow of the war the economy grew strongly, but there remained a legacy of shortages at a time when many sought material advancement. Historical writing on consumer culture is burgeoning internationally, and starting to emerge in New Zealand. There is already some local discussion of consumption in the post-war period, particularly with respect to clothing, embodiment and housing.1 This is an important area for study because, as Peter Gibbons points out, the consumption of goods — along with the needs they express and the desires they engender — deeply affects individual lives and social relationships.2 A number of aspects of consumption lend themselves to historical analysis, including the economic, the symbolic, the moral and the political. By exploring the political aspects of consumption and their relationships to these other strands, we can see how intense contestation over the symbolic meaning of consumption and its relationship to production played a pivotal role in defining the differences between the Labour government and the National opposition in the 1940s. -

A Diachronic Study of Unparliamentary Language in the New Zealand Parliament, 1890-1950

WITHDRAW AND APOLOGISE: A DIACHRONIC STUDY OF UNPARLIAMENTARY LANGUAGE IN THE NEW ZEALAND PARLIAMENT, 1890-1950 BY RUTH GRAHAM A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Linguistics Victoria University of Wellington 2016 ii “Parliament, after all, is not a Sunday school; it is a talking-shop; a place of debate”. (Barnard, 1943) iii Abstract This study presents a diachronic analysis of the language ruled to be unparliamentary in the New Zealand Parliament from 1890 to 1950. While unparliamentary language is sometimes referred to as ‘parliamentary insults’ (Ilie, 2001), this study has a wider definition: the language used in a legislative chamber is unparliamentary when it is ruled or signalled by the Speaker as out of order or likely to cause disorder. The user is required to articulate a statement of withdrawal and apology or risk further censure. The analysis uses the Communities of Practice theoretical framework, developed by Wenger (1998) and enhanced with linguistic impoliteness, as defined by Mills (2005) in order to contextualise the use of unparliamentary language within a highly regulated institutional setting. The study identifies and categorises the lexis of unparliamentary language, including a focus on examples that use New Zealand English or te reo Māori. Approximately 2600 examples of unparliamentary language, along with bibliographic, lexical, descriptive and contextual information, were entered into a custom designed relational database. The examples were categorised into three: ‘core concepts’, ‘personal reflections’ and the ‘political environment’, with a number of sub-categories. This revealed a previously unknown category of ‘situation dependent’ unparliamentary language and a creative use of ‘animal reflections’. -

"Unfair" Trade?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Garcia, Martin; Baker, Astrid Working Paper Anti-dumping in New Zealand: A century of protection from "unfair" trade? NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper, No. 39 Provided in Cooperation with: New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Wellington Suggested Citation: Garcia, Martin; Baker, Astrid (2005) : Anti-dumping in New Zealand: A century of protection from "unfair" trade?, NZ Trade Consortium Working Paper, No. 39, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER), Wellington This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/66072 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

Debate Recovery? Ch

JANUARY 16, 1976 25 CENTS VOLUME 40/NUMBER 2 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY/PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE actions nee - DEBATE U.S. LEFT GROUPS DISCUSS VITAL ISSUES IN REVOLUTION. PAGE 8. RECOVERY? MARXIST TELLS WHY ECONOMIC UPTURN HAS NOT BROUGHT JOBS. PAGE 24. RUSSELL MEANS CONVICTED IN S.D. FRAME-UP. PAGE 13. Original murder charges against Hurricane Carter stand exposed and discredited. Now New Jersey officials seek to keep him' behind bars on new frame-up as 'accomplice/ See page 7. PITTSBURGH STRIKERS FIGHT TO SAVE SCHOOLS. PAGE 14. CH ACTION TO HALT COP TERROR a Ira me- IN NATIONAL CITY. PAGE 17. In Brief NO MORE SHACKLES FOR SAN QUENTIN SIX: The lation that would deprive undocumented workers of their San Quentin Six have scored a victory with their civil suit rights. charging "cruel and unusual punishment" in their treat The group's "Action Letter" notes, "[These] bills are ment by prison authorities. In December a federal judge nothing but the focusing on our people and upon all Brown THIS ordered an end to the use of tear gas, neck chains, or any and Asian people's ability to obtain and keep a job, get a mechanical restraints except handcuffs "unless there is an promotion, and to be able to fight off discrimination. But imminent threat of bodily harm" for the six Black and now it will not only be the government agencies that will be WEEK'S Latino prisoners. The judge also expanded the outdoor qualifying Brown people as to whether we have the 'right' to periods allowed all prisoners in the "maximum security" be here, but every employer will be challenging us at every MILITANT Adjustment Center at San Quentin. -

Political Leadership and Aotearoa/New Zealand’S 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: MacLean, Malcolm ORCID: 0000-0001-5750-4670 (1998) From Old Soldiers to Old Youth: Political Leadership and Aotearoa/New Zealand’s 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour. Occasional Papers in Football Studies, 1 (1). pp. 22-36. Official URL: http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/FootballStudies/1998/FS0101a.pdf EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/2895 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: MacLean, Malcolm (1998). From Old Soldiers to Old Youth: Political Leadership and Aotearoa/New Zealand’s 1981 Springbok Rugby Tour. Occasional Papers in Football Studies, 1 (1), 22-36. Published in Occasional Papers in Football Studies, and available online from: http://library.la84.org/SportsLibrary/FootballStudies/1998/FS0101a.pdf We recommend you cite the published (post-print) version. -

Life Stories of Robert Semple

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. From Coal Pit to Leather Pit: Life Stories of Robert Semple A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of a PhD in History at Massey University Carina Hickey 2010 ii Abstract In the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography Len Richardson described Robert Semple as one of the most colourful leaders of the New Zealand labour movement in the first half of the twentieth century. Semple was a national figure in his time and, although historians had outlined some aspects of his public career, there has been no full-length biography written on him. In New Zealand history his characterisation is dominated by two public personas. Firstly, he is remembered as the radical organiser for the New Zealand Federation of Labour (colloquially known as the Red Feds), during 1910-1913. Semple’s second image is as the flamboyant Minister of Public Works in the first New Zealand Labour government from 1935-49. This thesis is not organised in a chronological structure as may be expected of a biography but is centred on a series of themes which have appeared most prominently and which reflect the patterns most prevalent in Semple’s life. The themes were based on activities which were of perceived value to Semple. Thus, the thematic selection was a complex interaction between an author’s role shaping and forming Semple’s life and perceived real patterns visible in the sources. -

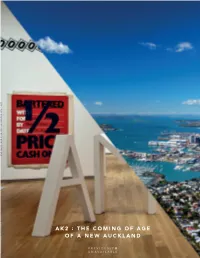

Ak2 : the Coming of Age of a New Auckland

AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE A NEW AUCKLAND PREVIOUSLY UNAVAILABLE PREVIOUSLY AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE OF A NEW AUCKLAND AK2: The Coming of Age of a New Auckland Published June 2014 by: Previously Unavailable www.previously.co [email protected] © 2014 Previously Unavailable Researched, written, curated & edited by: James Hurman, Principal, Previously Unavailable Acknowledgements: My huge thanks to all 52 of the people who generously gave their time to be part of this study. To Paul Dykzeul of Bauer Media who gave me access to Bauer’s panel of readers to complete the survey on Auckland pride and to Tanya Walshe, also of Bauer Media, who organised and debriefed the survey. To Jane Sweeney of Anthem who connected me with many of the people in this study and extremely kindly provided me with the desk upon which this document has been created. To the people at ATEED, Cooper & Company and Cheshire Architects who provided the photos. And to Dick Frizzell who donated his time and artistic eforts to draw his brilliant caricature of a New Aucklander. You’re all awesome. Thank you. Photo Credits: p.14 – Basketballers at Wynyard – Derrick Coetzee p.14 – Britomart signpost – Russell Street p.19 - Auckland from above - Robert Linsdell p.20 – Lantern Festival food stall – Russell Street p.20 – Art Exhibition – Big Blue Ocean p.40 – Auckland Museum – Adam Selwood p.40 – Diner Sign – Abaconda Management Group p.52 – Lorde – Constanza CH SOMETHING’S UP IN AUCKLAND “We had this chance that came up in Hawkes Bay – this land, two acres, right on the beach. -

(No. 23)Craccum-1976-050-023.Pdf

A u rb la n d University Student Paper to make these points at all. He was In April and May of 197 2 the obviously sensitive about the fact short-lived Sunday Herald ran a that his articles conflicted with the series of four articles dealing with official fiction that ours is a classless the men who dominate New Zealand society, and was trying to salvage as commerce. The first article was much of the myth as possible. headed Elite Group has Reins on The formation of oligarchies Key Directorships, and it justified is a strong New Zealand characterist this title with the contention that ic - it doesn’t only happen in the “a large proportion of private assets business world. The situation could in New Zealand are under the almost be described as ‘Government control of a group which probably m M m by In-group’. This characteristic is numbers less than 300 people. more costy than sinister - not that Control of commerce in New it makes any difference. The effect Zealand seems to be exercised is more important than the motive, through large companies which have and the effect in this case is that the interlocking directorates. It is country is suffocating under the possible to construct a circular uninspired direction of a number of chain which leads from point A little in-groups. Practically every right through the economy back to institution and organisation in New point A.” W EALTH Zealand - whether it be a university The anonymous author selected administration or a students’ a company at random - New association, Federated Farmers or Zealand Breweries - and listed the the Federation of Labour - is run by connections that its directors had POWER with other companies. -

![[Front Matter]NZJH 43 1 00.Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0402/front-matter-nzjh-43-1-00-pdf-1220402.webp)

[Front Matter]NZJH 43 1 00.Pdf

THE NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF HISTORYTHE NEW ZEALAND JOURNAL OF HISTORY VOL.43, No.1 APRIL 2009 VOL.43, No.1, APRIL 2009 APRIL VOL.43, No.1, THE UNIVERSITY OF AUCKLAND TE WHARE WÄNANGA O TAMAKI MAKAURAU NEW ZEALAND Editors: Caroline Daley & Deborah Montgomerie Associate Editors: Judith Bassett Judith Binney Malcolm Campbell Raewyn Dalziel Aroha Harris Review Editor, Books: Greg Ryan Review Editor, History in Other Media: Bronwyn Labrum Editorial Assistants: Jennifer Ashton Barbara Batt Business Manager: Nisha Saheed Editorial Advisory Group: Tony Ballantyne Washington University in St Louis Barbara Brookes University of Otago Giselle Byrnes University of Waikato Cathy Coleborne University of Waikato Bronwyn Dalley Ministry for Culture and Heritage Anna Green University of Exeter Chris Hilliard University of Sydney Kerry Howe Massey University, Albany Jim McAloon Victoria University of Wellington John E. Martin Parliamentary Historian, Wellington Philippa Mein Smith University of Canterbury The New Zealand Journal of History is published twice yearly, in April and October, by The University of Auckland. Subscription rates for 2010, payable in advance, post free: domestic $50.00 (incl. GST); overseas $NZ60.00. Student subscription $30.00 (incl. GST). Subscriptions and all business correspondence should be addressed to the Business Manager New Zealand Journal of History Department of History The University of Auckland Private Bag 92019 Auckland New Zealand or by electronic mail to: [email protected] Articles and other correspondence should be addressed to the Editor at the same address. Intending contributors should consult the style sheet at http://www.arts.auckland.ac.nz/his/nzjh/ Back numbers available: $10.00 (incl. -

Internal Assessment Resource History for Achievement Standard 91002

Exemplar for internal assessment resource History for Achievement Standard 91002 Exemplar for Internal Achievement Standard History Level 1 This exemplar supports assessment against: Achievement Standard 91002 Demonstrate understanding of an historical event, or place, of significance to New Zealanders An annotated exemplar is an extract of student evidence, with a commentary, to explain key aspects of the standard. These will assist teachers to make assessment judgements at the grade boundaries. New Zealand Qualification Authority To support internal assessment from 2014 © NZQA 2014 Exemplar for internal assessment resource History for Achievement Standard 91002 Grade Boundary: Low Excellence For Excellence, the student needs to demonstrate comprehensive understanding of an 1. historical event, or place, of significance to New Zealanders. This involves including a depth and breadth of understanding using extensive supporting evidence, to show links between the event, the people concerned and its significance to New Zealanders. In this student’s evidence about the Maori Land Hikoi of 1975, some comprehensive understanding is demonstrated in comments, such as why the wider Maori community became involved (3) and how and when the prime minister took action against the tent embassy (6). Breadth of understanding is demonstrated in the wide range of matters that are considered (e.g. the social background to the march, the nature of the march, and the description of a good range of ways in which the march was significant to New Zealanders). Extensive supporting evidence is provided regarding the march details (4) and the use of specific numbers (5) (7) (8). To reach Excellence more securely, the student could ensure that: • the relevance of some evidence is better explained (1) (2), or omitted if it is not relevant • the story of the hikoi is covered in a more complete way.