Advertising Alcohol in New Zealand, C.1900-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alcoholic Beverages Manufacturing Projects. Profitable Business Ideas in Alcohol Industry

www.entrepreneurindia.co Introduction An alcoholic beverage is a drink containing ethanol, commonly known as alcohol. Alcoholic beverages are divided into three general classes-beers, wines, and spirits. Alcoholic beverages are consumed universally. The demand for these beverages has changed in the last few years, considering the on/off premises consumption trends. Drinking alcohol plays an important social role in many cultures. Most countries have laws regulating the production, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages. Some countries ban such activities entirely, but alcoholic drinks are legal in most parts of the world. www.entrepreneurindia.co India is one of the fastest growing alcohol markets in the world. Rapid increase in urban population, sizable middle class population with rising spending power, and a sound economy are certain significant reasons behind increase in consumption of alcohol in India. The Indian alcohol market is growing at a CAGR of 8.8% and it is expected to reach 16.8 Billion liters of consumption by the year 2022. The popularity of wine and vodka is increasing at a remarkable CAGR of 21.8% and 22.8% respectively. India is the largest consumer of whiskey in the world and it constitutes about 60% of the IMFL market. www.entrepreneurindia.co India alcoholic beverage industry is one of the biggest alcohol industry across the globe only behind from two major countries such as China and Russia. Growing demand for alcoholic beverages in India is majorly attributed to the huge young population base and growing consumption of alcohol by the young generation as well as rising disposable income is strengthening the industry growth. -

TTB FY 2010 Congressional Budget Justification

Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Mission Statement Our mission is to collect alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and ammunition excise taxes that are rightfully due, to protect the consumer of alcohol beverages through compliance programs that are based upon education and enforcement of the industry to ensure an effectively regulated marketplace; and to assist industry members to understand and comply with Federal tax, product, and marketing requirements associated with the commodities we regulate. Program Summary by Budget Activity Dollars in Thousands Appropriation FY 2008 FY 2009 FY 2010 Enacted Enacted Request $ Change % Change Collect the Revenue $47,693 $50,524 $52,500 $1,976 3.9% Protect the Public $45,822 $48,541 $52,500 $3,959 8.2% Total Appropriated Resources $93,515 $99,065 $105,000 $5,935 6.0% Total FTE 544 525 537 12 2.3% Note: FY 2010 Total Appropriated Resources includes $80 million in offsetting receipts collections from fee revenues. To the extent that these allocations differ from the Budget, the reader should refer to the figures presented in this document. FY 2010 Priorities • Collect the roughly $22 billion in excise taxes rightfully due to the federal government. • Process permit applications that allow for the commencement of new alcohol and tobacco businesses. • Process applications for Certificates of Label Approval required to introduce alcohol beverage products into the marketplace. • Conduct investigations to effectively administer the Internal Revenue Code and Federal Alcohol Administration Act provisions with the objective to minimize tax fraud and diversion risks. • Complete audits of large and at-risk taxpayers who pay federal excise taxes. -

The Alcohol Textbook 4Th Edition

TTHEHE AALCOHOLLCOHOL TEXTBOOKEXTBOOK T TH 44TH EEDITIONDITION A reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries Edited by KA Jacques, TP Lyons and DR Kelsall Foreword iii The Alcohol Textbook 4th Edition A reference for the beverage, fuel and industrial alcohol industries K.A. Jacques, PhD T.P. Lyons, PhD D.R. Kelsall iv T.P. Lyons Nottingham University Press Manor Farm, Main Street, Thrumpton Nottingham, NG11 0AX, United Kingdom NOTTINGHAM Published by Nottingham University Press (2nd Edition) 1995 Third edition published 1999 Fourth edition published 2003 © Alltech Inc 2003 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright holder except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publishers. ISBN 1-897676-13-1 Page layout and design by Nottingham University Press, Nottingham Printed and bound by Bath Press, Bath, England Foreword v Contents Foreword ix T. Pearse Lyons Presient, Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA Ethanol industry today 1 Ethanol around the world: rapid growth in policies, technology and production 1 T. Pearse Lyons Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA Raw material handling and processing 2 Grain dry milling and cooking procedures: extracting sugars in preparation for fermentation 9 Dave R. Kelsall and T. Pearse Lyons Alltech Inc., Nicholasville, Kentucky, USA 3 Enzymatic conversion of starch to fermentable sugars 23 Ronan F. -

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola

REFERENCE LIST: 10 (4) Legat, Nicola. "South - the Endurance of the Old, the Shock of the New." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 60-75. Roger, W. "Six Months in Another Town." Auckland Metro 40 (1984): 155-70. ———. "West - in Struggle Country, Battlers Still Triumph." Auckland Metro 5, no. 52 (1985): 88-99. Young, C. "Newmarket." Auckland Metro 38 (1984): 118-27. 1 General works (21) "Auckland in the 80s." Metro 100 (1989): 106-211. "City of the Commonwealth: Auckland." New Commonwealth 46 (1968): 117-19. "In Suburbia: Objectively Speaking - and Subjectively - the Best Suburbs in Auckland - the Verdict." Metro 81 (1988): 60-75. "Joshua Thorp's Impressions of the Town of Auckland in 1857." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 35 (1979): 1-8. "Photogeography: The Growth of a City: Auckland 1840-1950." New Zealand Geographer 6, no. 2 (1950): 190-97. "What’s Really Going On." Metro 79 (1988): 61-95. Armstrong, Richard Warwick. "Auckland in 1896: An Urban Geography." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1958. Elphick, J. "Culture in a Colonial Setting: Auckland in the Early 1870s." New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 10 (1974): 1-14. Elphick, Judith Mary. "Auckland, 1870-74: A Social Portrait." M.A. thesis (History), University of Auckland, 1974. Fowlds, George M. "Historical Oddments." Journal of the Auckland Historical Society 4 (1964): 35. Halstead, E.H. "Greater Auckland." M.A. thesis (Geography), Auckland University College, 1934. Le Roy, A.E. "A Little Boy's Memory of Auckland, 1895 to Early 1900." Auckland-Waikato Historical Journal 51 (1987): 1-6. Morton, Harry. -

ADDRESSES and CONTRIBUTED ARTICLES Alcohol and the Chemical Industries’ by J

569 THE JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL AND ENGINEERING CHEMISTRY Vol. 13, No. 6 ADDRESSES AND CONTRIBUTED ARTICLES Alcohol and the Chemical Industries’ By J. M. Doran INDUSTRIALALCOHOL AND CHBMICALDIVISION, INTBRNAL RBVBNUB BURBAU,WASHINGTON, D. C. To appear before a gathering of representative industrial condition laid down in the 1913 Act was that the alcohol be chemists engaged in practically every branch of chemical ac- rendered unfit for beverage use. No limitation as to its use in tivity and to call attention to the essential relationship of the the arts and industries, or for fuel, light and power, or prohibition alcohol industry to the other chemical industries would, at first against its use for liquid medicinal purposes was set out. thought, seem so elemental and unnecessary as to be almost ab- Since the 1913 Act, the Department has authorized the use of surd. The chemist knows that alcohol as a solvent bears the specially denatured alcohol in medicinal preparations solely for same relation to organic chemistry that water does to inorganic external use. Tincture of iodine and the official soap liniments chemistry. It may be regarded along with sulfuric acid, nitric were among the earlier authorizations. acid, and the alkalies as among the chemical compounds of With the opening of the war in Europe in 1914 the withdrawal greatest value and widest use. of alcohol free of tax for denaturation increased rapidly. When To enumerate to the chemist the compounds in the prepara- we became involved in 1917 it became a question of sufficient ca- tion of which ethyl alcohol is necessarily used, either as solvent or pacity to supply the demand. -

Alcohol Industry Actions to Reduce Harmful Drinking in Europe: Public Health Or Public Relations? Katherine Robaina1, Katherine Brown2, Thomas F

341 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Alcohol industry actions to reduce harmful drinking in Europe: public health or public relations? Katherine Robaina1, Katherine Brown2, Thomas F. Babor1, Jonathan Noel3 1 University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Department of Community Medicine and Health Care, Farmington, Connecticut, United States of America 2 Institute of Alcohol Studies, London, United Kingdom 3 Johnson and Wales University, Department of Health Science, Providence, Rhode Island, United States of America Corresponding author: Thomas F. Babor (email: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Context: In 2012 an inventory of >3500 industry actions was compiled Results: Only 1.9% of CSR activities were supported by evidence of by alcohol industry bodies in support of the Global strategy to reduce the effectiveness, 74.5% did not conform to Global strategy categories and harmful use of alcohol, adopted by WHO in 2010. only 0.1% were consistent with “best buys” for prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Of the three segments, trade associations were Objectives: This study critically evaluated a sample of these corporate social the most likely to employ a strategic CSR approach and engage in partnerships responsibility (CSR) activities conducted in Europe. with government. A statistically significant correlation was found between Methods: A content analysis was performed on a sample of 679 CSR volume of CSR activities and alcohol industry revenue, as well as market size. activities from three industry segments (producers, trade associations and Conclusion: CSR activities conducted by the alcohol industry in the WHO social-aspects organizations) described on an industry-supported website. European Region are unlikely to contribute to WHO targets but may have Volume of CSR activity was correlated with country-level data reflecting a public-relations advantage for the alcohol industry. -

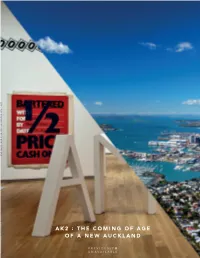

Ak2 : the Coming of Age of a New Auckland

AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE A NEW AUCKLAND PREVIOUSLY UNAVAILABLE PREVIOUSLY AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE OF A NEW AUCKLAND AK2: The Coming of Age of a New Auckland Published June 2014 by: Previously Unavailable www.previously.co [email protected] © 2014 Previously Unavailable Researched, written, curated & edited by: James Hurman, Principal, Previously Unavailable Acknowledgements: My huge thanks to all 52 of the people who generously gave their time to be part of this study. To Paul Dykzeul of Bauer Media who gave me access to Bauer’s panel of readers to complete the survey on Auckland pride and to Tanya Walshe, also of Bauer Media, who organised and debriefed the survey. To Jane Sweeney of Anthem who connected me with many of the people in this study and extremely kindly provided me with the desk upon which this document has been created. To the people at ATEED, Cooper & Company and Cheshire Architects who provided the photos. And to Dick Frizzell who donated his time and artistic eforts to draw his brilliant caricature of a New Aucklander. You’re all awesome. Thank you. Photo Credits: p.14 – Basketballers at Wynyard – Derrick Coetzee p.14 – Britomart signpost – Russell Street p.19 - Auckland from above - Robert Linsdell p.20 – Lantern Festival food stall – Russell Street p.20 – Art Exhibition – Big Blue Ocean p.40 – Auckland Museum – Adam Selwood p.40 – Diner Sign – Abaconda Management Group p.52 – Lorde – Constanza CH SOMETHING’S UP IN AUCKLAND “We had this chance that came up in Hawkes Bay – this land, two acres, right on the beach. -

PARTIES OR POLITICS: Wellington's I.R.A. 1922-1928

Parties or Politics: Wellington’s I.R.A. 1922-28 PARTIES OR POLITICS: Wellington's I.R.A. 1922-1928. The Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed in London in December 1921 and ratified in Dublin in January 1922, was a watershed for Irish communities abroad, albeit in a different sense than for those in Ireland. For the New Zealand Irish the Treaty creating the Irish Free State represented a satisfactory outcome to a struggle which for six years had drawn them into conflict with the wider New Zealand community. Espousing the cause of Ireland had been at a cost to domestic harmony in New Zealand but with ‘freedom’ for the homeland won, the colonial Irish1 could be satisfied that they done their bit and stood up for Ireland. The Treaty was an end point to the Irish issue for most Irish New Zealanders. Now it was time for those ‘at home’ to sort out the details of Ireland’s political arrangements as they saw fit. Political energies in New Zealand would henceforth be expended instead on local causes. For many Irish New Zealanders by 1922 this meant the socialist platform of the rising Labour Party. But not every local Irish patriot was satisfied with the Treaty or prepared to abandon the Republican ideal. Die-hard Republicans – and New Zealand had a few - saw the Treaty as a disgraceful sell-out of the Republic established in blood in Easter 1916. Between 1922 and 1928 therefore, a tiny band of Irish Republicans carried on a propaganda struggle in New Zealand, which vainly sought to rekindle the patriotic fervour of 1921 among the New Zealand Irish in support of the Republican faction in Ireland. -

2030 Vision for the Alcohol Beverages Industry

for the Alcohol Beverages REALISING POTENTIAL OUR Industry Vision Realising our potential 2030 2030 2 n times of crisis, Australians come together Our viticulture industry has developed into Ias a community. We give each other a world leader as a producer of premium, strength and support to rise to the challenges distinguished wines, coveted around the globe. we face as a nation. Most recently, we have Now the craft taking place in our distilleries been tested by the coronavirus pandemic, and breweries is also attracting the attention which has robbed some of us of loved ones, of global enthusiasts, as they win international placed strain on our physical and mental awards recognising their prestige, distinctive well-being and significantly impacted our Aussie-inspired tastes and the ingenuity of economy. We have been fortunate to avoid their creators. the devastation the virus has had on many countries around the world, and as a nation At the heart of the industry are its people: we are coming back stronger than ever. passionate, creative and entrepreneurial winemakers, distillers and brewers working But we need to pay particular attention to across the country to produce exceptional those industries and individuals who have beverages. The revenue produced by our local been more severely affected. Australians want alcohol beverage industry delivers benefits REALISING OUR POTENTIAL to return to our previous way of life: to spend right along the supply chain, bringing jobs and time with family and friends, to celebrate, money into our communities, including those to collaborate and to connect. For many in rural and regional Australia. -

The Green Ray and the Maoriland Irish Society in Dunedin, 1916-1922

“SHAMING THE SHONEENS1 ”: the Green Ray and the Maoriland Irish Society in Dunedin, 1916-1922. Irish issues played an unusually divisive role in New Zealand society between 1916 and 1922. Events in Ireland in the wake of the Easter 1916 Rising in Dublin were followed closely by a number of groups in New Zealand. For some the struggle for Irish independence was scandalous, a threat to the stability of Empire and final proof, if any were needed, of the fundamental unsuitability of Irish (Catholics) as citizens in New Zealand, the Greater Britain of the South Pacific.2 For others, particularly the ‘lace curtain’ Catholic bourgeoisie, events in Ireland were potentially a source of embarrassment, threatening to undermine a carefully cultivated accommodation between Irish ethnic identity, centred on the Catholic Church, and civic respectability amidst New Zealand’s Anglo- Protestant majority population.3 For a third group the rebellion and its aftermath were a stirring realisation of centuries old hopes, an unlooked for opportunity to fulfil the revolutionary dreams of generations of dead Irish patriots. This essay seeks to cast some fresh light on Irish issues in New Zealand from 1916 to 1922 by looking at a small group of ‘advanced Irish nationalists’ in Dunedin. These people were few in number and have left little evidence of their activities, let alone their motivations, organisational dynamics or long- term achievements. Yet their presence in Dunedin at all is worthy of some attention. There were genuine Irish ‘Sinn Féiners’ in New Zealand, recent arrivals who claimed intimate connections with ‘the martyrs of 1916’. -

In Developing Countries: Economic Growth and the Alcohol Industry

Blackwell Science, LtdOxford, UKADDAddiction0965-2140© 2006 Society for the Study of Addiction101EditorialEditorialEditorial EDITORIAL EDITORIAL doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01334.x A ‘perfect storm’ in developing countries: economic growth and the alcohol industry In late October 1991 unusual weather conditions created before outlining briefly how the threat can be coun- a major storm off the Eastern Atlantic Seaboard of the tered and abated. United States of America. Winds were above hurricane force, and waves up to 30 feet high were common from ECONOMIC GROWTH the coast of North Carolina to Nova Scotia (http:// www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/satellite/satelliteseye/cyclones/ Developing countries, especially in Latin America, have pfctstorm91/pfctstorm.html). The total damage caused had a mixed trend of economic growth in the past by the storm reached upwards of 200 million dollars. The 20 years. Nevertheless, and apart from specific develop- United States Weather Service, taking into account the ments in the alcohol industry, the globalization of the factors that combined to create this weather event, world economy plus economic development from within labeled it ‘the perfect storm’. A book describing the storm are leading to further growth in many of these countries. (Junger 1997) became a bestseller. A movie describing Economic growth in developing nations expands the the effects of the storm, and focusing in particular on the local alcohol industry and makes developing nations tar- loss at sea of a fishing boat, the Andrea Gail, and its crew gets of market expansion by the ever-growing transna- appeared in the USA in 2000. tional producers of alcoholic beverages. -

A Flight of Tax Issues for the Alcohol Industry

Buffalo Intellectual Property Law Journal Volume 12 Number 1 2018-01-01 Article 7 1-1-2018 A Flight of Tax Issues for the Alcohol Industry Dash DeJarnatt Bryan Law Firm Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffaloipjournal Recommended Citation Dash DeJarnatt, A Flight of Tax Issues for the Alcohol Industry, 12 Buff. Intell. Prop. L.J. 121 (2018). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffaloipjournal/vol12/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Buffalo Intellectual Property Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ University at Buffalo School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A FLIGHT OF TAX ISSUES FOR THE ALCOHOL INDUSTRY' DASH DEJARNATT 2 I. INTRODUCTION. .................................... 122 II. HISTORY OF ALCOHOL TAXATION............. ...... 122 A. 1 7 TH AND 18TH CENTURYENGLAND ............. 123 B. 18TH AND 19TH CENTURYAMERICA.................. 125 C. 20' CENTURYAMERICA ................ ...... 128 III. UNIQUE AND IMPORTANT TAX ISSUES FOR THE ALCOHOL INDUSTRY. .......................................... 129 A. Excise Taxes. .......................... 130 1. FederalExcise Taxes.. .......... 130 a. Rates, Fees, and Reporting Requirements... ............ 130 2. Tax Bonds... .................... 133 a. Wine Bond.... ........... 134 b. Brewer's Bond..... .......... 135 c. DistilledSpirits Bond...... .... 136 d. Impacts of.Bonding Requirement.. 137 IV. STATE AND LOCAL TAXES .......................... 139 V. TAXATION OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY............. 141 A. Characterization....... ....... ........ 142 This article was authored prior to the 2017 Tax Reform. 2 Dash DeJamatt, J.D., LL.M, is an associate attorney at the Bryan Law Firm in Bozeman, Montana.