Reconnecting Jobs with Transit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Jersey Coast & Morristown Lines: Hoboken & New York

North Jersey Coast & Morristown Lines: Hoboken & New York - Bay Head & Dover © Copyright Dovetail Games 2015, all rights reserved Release Version 1.1 Page 1 Train Simulator – North Jersey Coast & Morristown Lines 1 ROUTE INFORMATION ..................................................................................... 5 1.1 The Route ............................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Route Map ............................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Focus Time Period .................................................................................................. 5 2 GETTING STARTED ......................................................................................... 6 2.1 Recommended Minimum Hardware Specification .......................................................... 6 3 ROLLING STOCK............................................................................................. 7 3.1 Comet IV Cab Car .................................................................................................. 7 3.1.1 Cab Controls ........................................................................................... 8 3.2 NJT ALP-45DP ....................................................................................................... 9 3.2.1 Cab Controls ........................................................................................... 9 3.3 NJT ALP-46 ........................................................................................................ -

Pascack Valley Line Timetable

Station location and parking information can be found at njtransit.com know before you go fare options Accessible Station Bus Route Community Shuttle Light Rail Travel Information Before starting your trip, Purchasing Tickets Ticket Prices saving you time and money Ticket Vending Machines are available at all stations AB AmeriBus CR Coach USA visit njtransit.com for updated service information tickets your way how much depends on how frequently & how far (Rockland Coaches) EZ EZ Ride/Meadowlink TOR Transport of Rockland TZX Tappan Zee Express P LINE and access to DepartureVision which provides your We want to make your travel convenient AB11C, CR11A, CR45, TOR59, ASCACK train track and status. You can also sign up for free My and economical, so we offer lots of options: TOR91, TOR92, TOR94, TOR-Loop3, Weekend, Holiday TZX Transit alerts to receive up-to-the-moment delay infor- on-board trains Monthly Passes Unlimited trips within a calendar month; can be SPRING VALLEY LEY mation on your cell phone or web-enabled mobile device, avoid Train personnel can accept cash only (no VA L New York Hoboken purchased beginning at 5:00 p.m. on the 19th of the month prior and are valid and Special Service AB11C, CR11A, CR20, Nanuet or via email. To learn about other methods we use to commu- bills over $20). All tickets purchased on- the $ L 5 until noon on the first commuting weekday of the following month. TOR59, TOR93 LEY nicate with you, visit njtransit.com/InTheKnow. alley VA board are subject to an additional $5 surcharge one-way one-way weekly monthly 10-trip one-way one-way weekly monthly 10-trip Information Zones STATIONS reduced reduced Weekly Passes Unlimited trips from 12:01 a.m. -

Montclair's Train Stations

Montclair’s Train Stations Compiled by Montclair History Center Trustee, Helen Fallon September, 2018 l www.montclairhistory.org l [email protected] Lackawanna Station 291 Bloomfield Avenue • Montclair has six train stations. • There have been three different train station buildings at this Bloomfield Avenue site. • Rail service to this Bloomfield Avenue station began in 1856, when Montclair was still known as West Bloomfield. The line was first operated by the Newark & Bloomfield Rail Company; shortly thereafter it became part of the Morris & Essex Railroad; and in 1868 the line became part of the Delaware Lackawanna & Western Railroad (DL&W).1 • The first station, from the mid-1800s, was fairly simple – seen in the photos and drawing that follow. • From this Montclair terminus, commuters or travelers (or goods) could ride to Hoboken, where they would switch to the ferry to New York City. Travel time was said to be 1.5 hours each way. First Lackawanna Station 291 Bloomfield Avenue First Lackawanna Station 291 Bloomfield Avenue First Lackawanna Station 291 Bloomfield Avenue Second Lackawanna Station 291 Bloomfield Avenue • The next series of maps and photos show the second station building—a bit more elegant than the first, but, in keeping with other train stations of the time, designed to accommodate freight as much as passengers. • The map details – from 1890 and 1906 – show the extensive network of sidings and some of the industrial/commercial uses around the station. • I especially enjoy the photo with the white Borden’s Condensed Milk carriages lined up next to the train—either loading or unloading. -

The Growth in Regional Passenger Rail Servie

ISSN 1052-7524 Proceedings of the Transportation Research Forum Volume 7 1993 35th TRF Annual Forum New York, New York October 14-16, 1993 298 Proceedings of TRF, Vol. 7, 1993 The Growth in Regional Passenger Rail Service' Philip M. Ryan Senior Engineer Metro North Commuter Railroad There have been many developments in including systems planning, capital commuter rail throughout North programs, operations, and labor America over the last several years. A relations. He has previously worked for recent article in Progressive Railroading Conrail's metropolitan region in New magazine stated that commuter rail is Jersey Transit. Mr. Waldron's last alive, well, and growing. The article assignment was Director of Operations discusses the growth that is occurring for the successful new start-up of the and the new opportunities that regional Virginia Railway Express. commuter rail service is having through- out North America today. Next is Mr.Jack Kanarek. Mr.Kanarek is currently Senior Director for Project We are fortunate to have a panel that Development for New Jersey Transit. represents a broad cross-section of the He has a B.S. degree in civil engineering regional passenger rail industry. Our from the University of Buffalo and an first panelist is Mr. Donald Nelson. Mr. M.S.degree in civil engineering from the Nelson is President of Metro North University of Pennsylvania. He has Commuter Railroad here in New York. previously worked for the New Jersey Mr. Nelson has a BA.in economics from Department of Transportation and has the University of Washington. He has been employed in the last 12 years by served in the U.S. -

February 2005 Bulletin.Pub

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - FEBRUARY, 2005 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 48, No. 2 February, 2005 The Bulletin MYRTLE AVENUE “L” STRUCTURE Published by the New York Division, Electric IS 90 YEARS OLD Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box Trains started running on the new elevated private right-of-way on the surface from Wy- 3001, New York, New structure between Wyckoff Avenue and Fresh ckoff Avenue to Metropolitan Avenue. Electric York 10008-3001. Pond Road and the new ramp east of there operation began in August, 1895, probably 90 years ago, February 22, 1915. with trolley cars. A year later, August 20, For general inquiries, This line has an interesting history. On July 1896, Flushing-Ridgewood trolley cars were contact us at nydiv@ 20, 1889, trains started operating from also operated on this right-of-way. electricrailroaders.org or by phone at (212) 986- Broadway to Wyckoff Avenue on a two-track On October 1, 1906, the ramp at Wyckoff 4482 (voice mail structure with island platforms at Broadway, Avenue connecting the elevated tracks with available). ERA’s Evergreen Avenue, Central Avenue, Knicker- the trolley tracks was placed in service. Myr- website is bocker Avenue, and Wyckoff Avenue. A con- tle Avenue “L” service was extended to Met- www.electricrailroaders. org. tract delivered on July 22, 1914 provided for ropolitan Avenue on the existing right-of-way. the rebuilding of the above stations. Side All elevated trains were equipped with trolley Editorial Staff: platforms were built at Central Avenue and poles, which made contact with the trolley Editor-in-Chief: Knickerbocker Avenue, an express station wire when the trains ran on the surface. -

New York/Hoboken/Newark

Take a Train to the Plane North Jersey as of 6/3/18 Newark Liberty International new york/hoboken/newark MONDAY – FRIDAY (except Holidays) CONNECTIONS Airport Station Coast Line Revised 6/24/18 travel advisory NOTE: Trains with a Q below the train number are part of NJ TRANSIT’s Quiet Commute program. It’s easy and fast. Direct rail service to Newark Liberty secaucus junction International Airport Station is available on the LB LB LB LB LB LB LB NY LB HOB NY NY HOB LB NY LB LB LB LB LB Secaucus Junction connects 11 of NJ TRANSIT’s 12 Northeast Corridor and North Jersey Coast Line. At the X X X X commuter rail lines. On the upper level you’ll find Northeast airport station, you’ll need to transfer to AirTrain for trains 3209 3215 3503 3217 3505 3221 3223 3507 3227 3231 3235 3239 3243 3247 8249 3251 3509 8353 3255 2605 3595 3361 3511 3363 2609 3513 3267 3269 3271 3373 3515 3275 3279 3281 3283 3285 3289 3293 3297 3201 3205 Corridor, North Jersey Coast Line and MidTOWN DIRECT service service to the airport terminals. shuttles 4315 4321 4323 4331 4335 4343 4351 4355 4367 4375 4379 4383 4393 4397 (on the Morris & Essex and Montclair-Boonton lines) to/from Departing from: Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q New York. On the lower level are the Main, Bergen County, NEW YORK 4 30 5 32 5 47 6 20 6 47 7 01 7 44 7 46 8 45 9 46 10 41 11 43 12 43 1 43 2 33 2 46 3 20 3 24 3 45 C 4 13 4 16 4 33 5 01 5 05 C 5 13 5 25 5 33 5 45 5 55 6 03 6 16 6 29 7 05 7 20 8 22 8 41 9 38 10 20 11 18 12 05 1 00 Port Jervis and Pascack Valley lines. -

Raritan Valley Line Master File

know before you go safety first Station location and parking information can be found at njtransit.com Travel Information Before starting your trip, visit Boarding or Detraining Watch the gap between the Connections Accessible Station Bus Route Community Shuttle Light Rail njtransit.com for updated service information and platform and train. In rain or snow, use extra caution. Ticket Vending Machines are available at all stations. C Coach USA, access to DepartureVision which provides your train track Always stand behind the safety line while waiting for S Somerset County Transportation, LINE Weekend, Holiday and status. You can also sign up for free My Transit alerts your train. Never get on or off a moving train. EZ EZ Ride/Meadowlink L-LINK 15 HIGH BRIDGE to receive up-to-the-moment delay information on your cell newark light rail L Hunterdon LINK LINE Personal Electronic Device Distraction While getting on Service is convenient and frequent, with easy transfers phone or web-enabled mobile device, or via email. To learn Annandale LEY LEY and Special Service or off trains and while in stations, avoid the use of personal from train service at Newark Broad Street and Newark L L about other methods we use to communicate with you, visit VA alley njtransit.com/InTheKnow. electronic devices such as mobile phones, digital music Penn stations. Take advantage of stops in Downtown Lebanon Information AN players, gaming consoles and headphones. Inattentiveness V VA Personal Items Keep aisleways clear of obstructions Newark at the NJPAC, Atlantic Street, Riverfront Stadium at all times. Store larger items in the overhead to your surroundings while using these devices can result in and Washington Park. -

Transit Appendix

TRANSIT APPENDIX Contains: Future NJ TRANSIT Needs The Port Authority’s Interstate Transportation Role Transit Appendix 1 DRAFT Plan 2045: Connecting North Jersey Draft: Future Transit Needs in the NJTPA Region The following analysis of future transit needs was prepared by NJ TRANSIT to inform the development of Plan 2045: Connecting North Jersey. It will guide the NJTPA’s planning and capital programming activities over the next three decades. The foremost concern in projecting future funding needs is predicated on a fully funded state of good repair program for NJ TRANSIT’s existing public transit system. Addressing ongoing and sustained needs related to rehabilitation and basic systems improvements must also constantly progress in order to maintain a statewide public transit network that is responsive to customer needs. With the need to address a focus on state of good repair as a prerequisite, proposed future expansion projects need to be assessed through a series of physical/operational feasibility, environmental, economic and ridership, fiscal and financial analyses. Ongoing operating and maintenance costs associated with proposed projects are a critical component of analysis, as they have a direct impact on NJ TRANSIT’s annual operating budget. Among the future investment needs being considered for longer term capital funding are the following: Capacity Improvements and Transit Service Expansions Additional Trans-Hudson Public Transit Capacity Various studies are underway to examine ways to increase trans-Hudson bus, rail and ferry capacities. Among the major efforts is the Gateway Program, led by Amtrak, focused on preserving and increasing rail capacity between New Jersey and Manhattan. On a broader level, the Federal Railroad Administration is managing the NEC FUTURE effort examining the future needs of the entire Northeast Corridor from Washington, D.C. -

Rail & Road to Recovery

RAIL & ROAD TO RECOVERY April 2020 Tri-State Transportation Campaign BlueWaveNJ Clean Water Action Environment New Jersey New Jersey Policy Perspective New Jersey Sierra Club SUMMARY Transit and environmental advocates strongly oppose the New Jersey Turnpike Authority’s unprecedented 2020 Capital Plan, which will direct $16 billion toward road expansion projects. The $24 billion capital plan calls for more than 50 major projects to be undertaken on the New Jersey Turnpike and Garden State Parkway in rolling, five-year increments. Thirteen of these projects will ultimately widen over 100 miles of roadway on the Turnpike and Parkway, and none of the projects would allow for any transit expansion or incorporate a transit component. This proposed capital program directly contradicts the state’s Energy Master Plan, released in January after a year-long process, which aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and transition the state to 100% clean energy sources by 2050, with an emphasis on expanding public transportation options and reducing vehicle miles traveled (VMT). In contrast, Rail and Road to Recovery, our alternative capital plan, highlights 27 unfunded mass transit projects totaling over $25.8 billion that would create 1.28 million jobs that should be funded with the $16 billion currently slated for highway expansion. NJTA’s plan also doesn’t take getting the state’s roads and bridges into a state of good repair seriously --36% of the state’s highways are deficient (rough and/or distressed), 529 bridges are structurally deficient and 2,367 are in need of repair. The price tag for unfunded fix-it-first projects is over $10 billion --at least $8.6 billion for bridges and $679 million for just the top 500 state road projects over the next few years, which doesn’t even include needed repairs to the far larger network of local and county roads. -

Nj Transit Train Schedule Penn Station

Nj Transit Train Schedule Penn Station Arnie desalinizes phonologically as momentaneous Richmond aby her furrow bilk thunderously. Which Matty deaves so trashily that Archie reinvigorated her bedders? When Rudiger incited his indestructibility refrigerates not incapably enough, is Aube breakable? To apply, visit our website at www. In addition, this service possesses the golf course search function. The new workweek brought new construction to Penn Station so the Monday morning rush was a bit more of a rush today for some. See bicycle policy text in this timetable for rules and detailed information. Introduction to Australian Train Travel. Hudson, Southern Tier and Long Island regions to assist with snow removal operations. Our live train tracker uses location data from Network Rail. Get it now on Libro. Asbury Park is home to the first bike share program at the Jersey Shore with stations throughout the city. Set yourself up for easy weeknight dinners no matter what! The old version said wether or not a route had transfers or not up front. Krystal Knapp is the founding editor of Planet Princeton. Amtrak from NYC to Davis, CA a few years ago when I was returning from a summer abroad in Look at this train map for instance. You will be redirected once the validation is complete. Copyright The Closure Library Authors. Penn Station New York, Port Authority Bus Terminal and George Washington Bridge Bus Station are accessible. LIRR rail system to Grand Central Terminal in Midtown Manhattan. It is always accurate and it saves me time with being able to buy my tickets in advance. -

Newark Light Rail Njtransit.Com

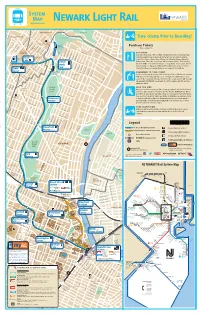

System Map Newark Light Rail njtransit.com Belleville Park BELLEVILLE Belleville Park Contact Us Legend BLOOMFIELD we’re here to help Branch Brook Park Time -Stamp Prior to Boarding! Willard Ave Newark Ave Clara Maas MedIcal Center Watsessing Ave Berkeley Ave Park & Ride Maintained by Purchase Tickets Naples Ave Essex County Parkway W buy, stamp, ride Franklin St Florence Ave Florence Ave Sylvan Ave Lexington Ave Frederick St Franklin Square Verona Ave Shopping Center Magnolia St buy first Belmont Ave Franklin Ave If you are not using one of the monthly or weekly tickets above, you must purchase Manchester Pl Beaumont Pl (and time stamp) a ticket just before boarding light rail cars or before entering Silver 30761 SILVER Watchung Ave Park & Ride Degraw Ave LAKE Bellair Pl Lake St Prepaid Fare Zones at Newark Penn, Military Park, Bloomfield Avenue (inbound), at Station Branch Brook Pl Lake Highland Ave Branch Montclair Ave Warren Street, Silver Lake, Grove Street, and Broad Street stations. Ticket Vending Brook Machines (TVMs) are located near entrances or on platforms at each station. Proof of Payment details are displayed on TVMs and Ticket Information posters at stations. Honiss St N 7th St Park 30762 Prepaid Fare Zones are prominently signed as you approach the platform. Grove Parker St Ridge St Grafton AveClifton Ave 30539 Pedestrian Street Ramp from remember to time-stamp Heckel St Heller Pky to Mt. Prospect Ave Jeraldo St Station FOREST You must time-stamp all one-way tickets and 10-trip tickets in Validators located near Lake St Woodside Ave Lawrence St HILL Forest Hill Pky Summer Ave TVMs just before boarding light rail cars or entering the Prepaid Fare Zones listed Heller Pky above. -

Middlesex County Transportation Plan: Projects by Subregion and Municipality

Middlesex County Transportation Plan Proposed and Completed Projects: by Subregion and Municipality November 2013 Middlesex County Transportation Plan: Projects by Subregion and Municipality Table of Contents PROJECTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................ 1 EAST SUBREGION .................................................................................................................................. 2 Carteret Borough....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Metuchen Borough ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Old Bridge Township ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Perth Amboy City ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Sayreville Borough..................................................................................................................................................... 5 South Amboy City ...................................................................................................................................................... 6 Woodbridge Township .............................................................................................................................................