34-Mcdonald (Biblio)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Facies Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Paleogene Huntingdon Formation at Abbotsford, British Columbia

Facies Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Paleogene Huntingdon Formation at Abbotsford, British Columbia Brett Hohs Tallentire Gilley B.Sc., Simon Fraser University, 1999 A THESIS SUBMInED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE In the DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES O Brett Hollis Tallentire Gilley, 2003 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY December, 2003 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Brett Hollis Tallentire Gilley Degree: Master of Science Title of Thesis: Facies Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Paleogene Huntingdon Formation at Abbotsford, British Columbia Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Glyn Williams-Jones Assistant Professor Dr. Peter Mustard Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Dr. ames MacEachern SupJ rvisory Associate Profess - Fvpf.Michael ~ilhn Ex rnal Examiner Doua4 as Colleae. De~t.of Geolosv & Anthropology Date Approved: ne 4 , 2 csz aw PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

1 Paleobotanical Proxies for Early Eocene Climates and Ecosystems in Northern North 2 America from Mid to High Latitudes 3 4 Christopher K

https://doi.org/10.5194/cp-2020-32 Preprint. Discussion started: 24 March 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. 1 Paleobotanical proxies for early Eocene climates and ecosystems in northern North 2 America from mid to high latitudes 3 4 Christopher K. West1, David R. Greenwood2, Tammo Reichgelt3, Alexander J. Lowe4, Janelle M. 5 Vachon2, and James F. Basinger1. 6 1 Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon, 7 Saskatchewan, S7N 5E2, Canada. 8 2 Dept. of Biology, Brandon University, 270-18th Street, Brandon, Manitoba R7A 6A9, Canada. 9 3 Department of Geosciences, University of Connecticut, Beach Hall, 354 Mansfield Rd #207, 10 Storrs, CT 06269, U.S.A. 11 4 Dept. of Biology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195-1800, U.S.A. 12 13 Correspondence to: C.K West ([email protected]) 14 15 Abstract. Early Eocene climates were globally warm, with ice-free conditions at both poles. Early 16 Eocene polar landmasses supported extensive forest ecosystems of a primarily temperate biota, 17 but also with abundant thermophilic elements such as crocodilians, and mesothermic taxodioid 18 conifers and angiosperms. The globally warm early Eocene was punctuated by geologically brief 19 hyperthermals such as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), culminating in the 20 Early Eocene Climatic Optimum (EECO), during which the range of thermophilic plants such as 21 palms extended into the Arctic. Climate models have struggled to reproduce early Eocene Arctic 22 warm winters and high precipitation, with models invoking a variety of mechanisms, from 23 atmospheric CO2 levels that are unsupported by proxy evidence, to the role of an enhanced 24 hydrological cycle to reproduce winters that experienced no direct solar energy input yet remained 25 wet and above freezing. -

A Review of Vertebrate Track-Bearing Formations

5 Lockley, M.G. & Lucas, S.G., eds., 2014, Fossil footprints of western North America: NMMNHS Bulletin 62 A REVIEW OF VERTEBRATE TRACK-BEARING FORMATIONS FROM THE MESOZOIC AND EARLIEST CENOZOIC OF WESTERN CANADA WITH A DESCRIPTION OF A NEW THEROPOD ICHNOSPECIES AND REASSIGNMENT OF AN AVIAN ICHNOGENUS RICHARD T. MCCREA1, LISA G. BUCKLEY1, A. GUY PLINT2, PHILIP J. CURRIE3, JAMES W. HAGGART4, CHARLES W. HELM1 AND S. GEORGE PEMBERTON5 1Peace Region Palaeontology Research Centre; Box 1540; Tumbler Ridge, British Columbia; V0C 2W0; CANADA; 2Department of Earth Sciences; University of Western Ontario; London, Ontario; N6A 5B7; CANADA; 3Department of Biological Sciences; University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta; T6G 2E9; CANADA; 4Geological Survey of Canada; 1500-605 Robson Street; Vancouver, British Columbia; V6B 5J3; CANADA; 5Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences; University of Alberta; Edmonton, Alberta; T6G 2E3; CANADA Abstract—The past quarter century has seen a marked increase in the recognition of fossil vertebrate tracksites in western Canada. Most of these finds were made in Alberta and British Columbia, but the Yukon Territory can lay claim to at least one tracksite and probably has the potential to yield more sites. The record of dinosaur tracks with skin impressions has increased dramatically, and is now represented by specimens of ankylosaurs, large ornithopods, small theropods and tyrannosauroids. Notable new finds include the first record of sauropods in Canada, evidence of herding behavior in ankylosaurs and the first pterosaur tracks in Canada. First discoveries of track specimens from several formations in western Canada include the Mountain Park Member of the Gates Formation in Alberta, and the Boulder Creek, Goodrich, Kaskapau, Cardium and Marshybank formations in northeastern British Columbia. -

OREGON GEOLOGY Published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries

OREGON GEOLOGY published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries VOLUME 47. NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1985 •-_Q OREGON GEOLOGY OIL AND GAS NEWS (ISSN 0164-3304) VOLUME 47, NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1985 Columbia County Exxon Corporation spudded its GPE Federal Com. I on Published monthly by the Oregon Department of Geology and Min September I. The well name is a change from GPE Federal 2, eraI Industries (Volumes 1 through 40 were entitled The Ore Bin). permitted for section 3. T. 4 N .. R. 3 W. Proposed total depth is 12.000 ft. The contractor is Peter Bawden. Governing Board Donald A. Haagensen, Chairman ............. Portland Coos County Allen P. Stinchfield .................... North Bend Amoco Production Company is drilling ahead on Weyer Sidney R. Johnson. .. Baker haeuser "F" I in section 10, T. 25 S .. R. 10 W. The well has a projected total depth of 5,900 ft and is being drilled by Taylor State Geologist ..................... Donald A. Hull Drilling. Deputy State Geologist. .. John D. Beaulieu Publications Manager/Editor ............. Beverly F. Vogt Lane County Leavitt's Exploration and Drilling Co. has drilled Merle I to Associate Editor . Klaus K.E. Neuendorf a total depth of 2,870 ft and plugged the well as a dry hole. The well. in section 25. T. 16 S .. R. 5 W .. was drilled 2 mi southeast of Main Office: 910 State Office Building, 1400 SW Fifth Ave nue. Portland 9720 I, phone (503) 229-5580. Ty Settles' Cindy I. drilled earlier this year to 1.600 ft. A.M. Jannsen Well Drilling Co. -

Virgil A. Frizzell, Jr, U.S. Geological Survey Msnlo Park, California

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF H7EERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PETROLOGY AND STRATIGRAPHY OF PALBOGENE NONMARINE SANDSTONES, CASCADE RANGE, WASHINGTON by Virgil A. Frizzell, Jr, U.S. Geological Survey Msnlo Park, California OiPEN-FIIE REPORT 79-1149 report is preliminary and has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Geological Survey standards and nomenclature ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to the following workers for sharing both samples and edifying thoughts: Rowland W. Tabor (RWT, prefix for sample numbers); John T. Whetten (W); Charles W. Walker (most Roslyn samples); James D. Vine (V); Randall L. Gresens (all Wenatchee samples); James C. Yount (Y); Betsey L. Mathieson (BL); and David R. Pevear (DP). Without patient teaching from both Charles E. Meyer and Charles W. Naeser I would not have been able to learn the fission track dating technique. Likewise, I am indebted to William R. Dickinson, Jonathan C, Matti, Robert R. Compton, Robert J. McLaughlin, Kenneth Helmold, Henry N. Ohlin, and Bret F. Cox for aiding my petrographic abilities. Preliminary drafts of this dissertation benefited from scrutiny by various colleagues but Roland W. Tabor, in particular, fearlessly improved both form and content. I am grateful for the contributions of both time and thought by these and other workers because they aided substantially in the completion of this dissertation. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES. ........................ vi LIST OF PLATES ......................... vii LIST OF TABLES ......................... vii ABSTRACT ............................ viii INTRODUCTION .......................... 1 REGIONAL GEOLOGY AND TECTONIC SETTING. ............. 3 Regional Geology ...................... 3 Pre-Tertiary Stratigraphy of Selected Geologic Units .... 3 Plate Tectonic Setting ................... 10 STRATIGRAPHIC UNITS. ...................... 18 Introduction to Stratigraphic Units. -

Ichnotaxonomy of the Eocene Green River Formation

Ichnotaxonomy of the Eocene Green River Formation, Soldier Summit and Spanish Fork Canyon, Uinta Basin, Utah: Interpreting behaviors, lifestyles, and erecting the Cochlichnus Ichnofacies By © 2018 Joshua D. Hogue B.S. Old Dominion University, 2013 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. Chair: Dr. Stephen T. Hasiotis Dr. Paul Selden Dr. Georgios Tsoflias Date Defended: May 1, 2018 ii The thesis committee for Joshua D. Hogue certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Ichnotaxonomy of the Eocene Green River Formation, Soldier Summit and Spanish Fork Canyon, Uinta Basin, Utah: Interpreting behaviors, lifestyles, and erecting the Cochlichnus Ichnofacies Chair: Dr. Stephen T. Hasiotis Date Approved: May 1, 2018 iii ABSTRACT The Eocene Green River Formation in the Uinta Basin, Utah, has a diverse ichnofauna. Nineteen ichnogenera and 26 ichnospecies were identified: Acanthichnus cursorius, Alaripeda lofgreni, c.f. Aquatilavipes isp., Aulichnites (A. parkerensis and A. tsouloufeidos isp. nov.), Aviadactyla (c.f. Av. isp. and Av. vialovi), Avipeda phoenix, Cochlichnus (C. anguineus and C. plegmaeidos isp. nov.), Conichnus conichnus, Fuscinapeda texana, Glaciichnium liebegastensis, Glaroseidosichnus ign. nov. gierlowskii isp. nov., Gruipeda (G. fuenzalidae and G. gryponyx), Midorikawapeda ign. nov. semipalmatus isp. nov., Planolites montanus, Presbyorniformipes feduccii, Protovirgularia dichotoma, Sagittichnus linki, Treptichnus (T. bifurcus, T. pedum, and T. vagans), and Tsalavoutichnus ign. nov. (Ts. ericksonii isp. nov. and Ts. leptomonopati isp. nov.). Four ichnocoenoses are represented by the ichnofossils—Cochlichnus, Conichnus, Presbyorniformipes, and Treptichnus—representing dwelling, feeding, grazing, locomotion, predation, pupation, and resting behaviors of organisms in environments at and around the sediment-water-air interface. -

The Geology and Mineralogy of Bentonites and Associated Rocks of the Chuckanut Formation, Mt

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Summer 1981 The Geology and Mineralogy of Bentonites and Associated Rocks of the Chuckanut Formation, Mt. Higgins Area, North Cascades, Washington Susan Kinder Cruver Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Cruver, Susan Kinder, "The Geology and Mineralogy of Bentonites and Associated Rocks of the Chuckanut Formation, Mt. Higgins Area, North Cascades, Washington" (1981). WWU Graduate School Collection. 645. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/645 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GEOLOGY AND MINERALOGY OF BENTONITES AND ASSOCIATED ROCKS OF THE CHUCKANUT FORMATION, MT. HIGGINS AREA, NORTH CASCADES, WASHINGTON A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Western Washington University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Susan Kinder Cruver MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. -

A Fossil Trionychid Turtle F Rom the Early Tertiary Chuckanut Formation

GeorgeE- Mustoe and SamuelP. Girouard,Jr., Geo ogy DepartrnentWestern Wash ngton Universty, Be ngharn Washngton 98225 A FossilTrionychid Turtle f rom the earlyTertiary Chuckanut Formation of NorthwesternWashington Abstract \Vrshington s \'e(cbrute fossilfecordi\ so sparsethate!en, discover] desenescarcful scnrtiny.AfossilizcdturlecaraDace tbund in 1960in fluviatilcsard stone of theChLrckanut Formaiion of wcnem WhatcomCounly $ a, ,,fig ini | 1idtnritrril.6aillcmheru1 the Tesludinoideasupedrmil). and an adjrcent bonefragmcnt was consideredtobceridence ofsome largeranimal. Rc cianina- tlon indicalcs (har the cafapacercpreserls a member of thc Trionychidae (soft shclled tufiles). Compulerired axial tomogmphv \Lrggeststhal the neafb) bone probably came from $c tu e. Trionychid fossils are abrndant in carl] Tefiiary rocks. bul rheir remarnsIa!c nol beenfound in younger rocks in ihe north$en resion. The only cxranrtrionychid found west of rhe MississipDi is ./l'i.,ir r \prlrl,rJ'ur.which inhabitssmall areasof eastemMontana and the Colorado Rivef fe8inn ot rh( "ourh$e\r. t'hr\rurrrrr- llon in geographicrange probablt resultedli|)lr global cooling lhar surted in the latc Eocene,and by habiut destructioncauscd b,"-episodes of nrounlainbuilding ihat begana lc$ million yearslarcr. Introduction raphy ofthe PaddenMenlber. but its age is prob ably lateEocene based on stmcturalrelationships The faunalrecord from the earlyTcftiary is sparse andpaleoclimatic evidence. Mustoe and Pevear evcnthough extensive sedimentary deposits liom (1983)described the poorly-preservedcarapace thisperiod are exposed on bothsides of theCas- asa memberof the SuperfamilyTestudinoidea, a cadeRange. These beds of shale,siltstone. sand- large group that includes pond turtles and land stone,conglomerate, and coal were depositedby tortoises.They guessedthat bone fragment ex- meanderingd!e$ that flowed westward across posedin cross-sectionview on one side of the thc broad lloodplain that coveredmuch of west- specimenwas part ofa rib bonefrom somelarger em and centralWashington prior to the uplift of animal. -

A Review of Paleobotanical Studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) Highlands Floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA. Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2015-0177.R1 Manuscript Type: Review Date Submitted by the Author: 02-Feb-2016 Complete List of Authors: Greenwood, David R.; Brandon University, Dept. of Biology Pigg, KathleenDraft B.; School of Life Sciences, Basinger, James F.; Dept of Geological Sciences DeVore, Melanie L.; Dept of Biological and Environmental Science, Keyword: Eocene, paleobotany, Okanagan Highlands, history, palynology https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Page 1 of 70 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) 2 Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA. 3 4 David R. Greenwood, Kathleen B. Pigg, James F. Basinger, and Melanie L. DeVore 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Draft 12 David R. Greenwood , Department of Biology, Brandon University, J.R. Brodie Science 13 Centre, 270-18th Street, Brandon, MB R7A 6A9, Canada; 14 Kathleen B. Pigg , School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, PO Box 874501, 15 Tempe, AZ 85287-4501, USA [email protected]; 16 James F. Basinger , Department of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 17 Saskatoon, SK S7N 5E2, Canada; 18 Melanie L. DeVore , Department of Biological & Environmental Sciences, Georgia 19 College & State University, 135 Herty Hall, Milledgeville, GA 31061 USA 20 21 22 23 Corresponding author: David R. Greenwood (email: [email protected]) 1 https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 70 24 A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) 25 Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada and Washington, USA. -

Washington Geology, V. 23, No. 3, September 1995

w V 0 WASHINGTON w VOL. 23, NO. 3 SEPTEMBER 1995 G EOLOG"I • INSIDE THIS ISSUE 1 Early Tertiary flowers, fruits. and seeds of Washington State and adjacent areas, p. 3 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF 1 Selected additions to the library of the Division of Geology and Earth Resources, p. 18 Natural Resources Jennifer M . Belcher - Co mmissio ner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor WASHINGTON Crown Jewel Project Reaches Milestone GEOLOGY Vol. 23, No. 3 Raymond Lasmanis, State Geologist September 1995 Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources Washi11g1011 Ceologr (ISSN 1058-2134) is published four times PO Box 47007, Olympia, WA 98504-7007 each year hy (he Washington State Department or Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Earth Resources. Thi~ puh lication is free upon request. The Division al so publishes b1il lc tins. information circulars. reports or investigations. geologic maps. and open -file reports. /\ li~t o r these publications will he A rter a lengthy evaluation process under the National Envi sent upon rcquc~l. ronment Policy Act (NEPA) and the State Environment Policy Act (SEPA), on June 30, 1995, the Draft Environmental Tm DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES pac t Statement. Crown Jewel Mine, Okanogan County, Wash ington, was issued by the lead agencies, U.S. Department of Raymo nd Lasmanis. Sr,11e Ge,,J,,,;i.<1 J. Eric Schuster. /1,1 l'i.1t1111t S rate Geolo,;isr Agriculture Forest ServiL:e allll the Washington State Deparr W1lli:1m S . Lingley, Jr., Ax,,i.<1111, t Stare G,•,,/o,;isr ment of Ecology. -

Geologic Map of Washington - Northwest Quadrant

GEOLOGIC MAP OF WASHINGTON - NORTHWEST QUADRANT by JOE D. DRAGOVICH, ROBERT L. LOGAN, HENRY W. SCHASSE, TIMOTHY J. WALSH, WILLIAM S. LINGLEY, JR., DAVID K . NORMAN, WENDY J. GERSTEL, THOMAS J. LAPEN, J. ERIC SCHUSTER, AND KAREN D. MEYERS WASHINGTON DIVISION Of GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-50 2002 •• WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF 4 r Natural Resources Doug Sutherland· Commissioner of Pubhc Lands Division ol Geology and Earth Resources Ron Telssera, Slate Geologist WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Ron Teissere, State Geologist David K. Norman, Assistant State Geologist GEOLOGIC MAP OF WASHINGTON NORTHWEST QUADRANT by Joe D. Dragovich, Robert L. Logan, Henry W. Schasse, Timothy J. Walsh, William S. Lingley, Jr., David K. Norman, Wendy J. Gerstel, Thomas J. Lapen, J. Eric Schuster, and Karen D. Meyers This publication is dedicated to Rowland W. Tabor, U.S. Geological Survey, retired, in recognition and appreciation of his fundamental contributions to geologic mapping and geologic understanding in the Cascade Range and Olympic Mountains. WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES GEOLOGIC MAP GM-50 2002 Envelope photo: View to the northeast from Hurricane Ridge in the Olympic Mountains across the eastern Strait of Juan de Fuca to the northern Cascade Range. The Dungeness River lowland, capped by late Pleistocene glacial sedi ments, is in the center foreground. Holocene Dungeness Spit is in the lower left foreground. Fidalgo Island and Mount Erie, composed of Jurassic intrusive and Jurassic to Cretaceous sedimentary rocks of the Fidalgo Complex, are visible as the first high point of land directly across the strait from Dungeness Spit. -

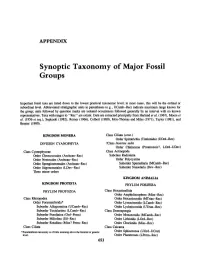

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida