Standardized Classification, Folksonomies, and Ontological Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metadata for Semantic and Social Applications

etadata is a key aspect of our evolving infrastructure for information management, social computing, and scientific collaboration. DC-2008M will focus on metadata challenges, solutions, and innovation in initiatives and activities underlying semantic and social applications. Metadata is part of the fabric of social computing, which includes the use of wikis, blogs, and tagging for collaboration and participation. Metadata also underlies the development of semantic applications, and the Semantic Web — the representation and integration of multimedia knowledge structures on the basis of semantic models. These two trends flow together in applications such as Wikipedia, where authors collectively create structured information that can be extracted and used to enhance access to and use of information sources. Recent discussion has focused on how existing bibliographic standards can be expressed as Semantic Metadata for Web vocabularies to facilitate the ingration of library and cultural heritage data with other types of data. Harnessing the efforts of content providers and end-users to link, tag, edit, and describe their Semantic and information in interoperable ways (”participatory metadata”) is a key step towards providing knowledge environments that are scalable, self-correcting, and evolvable. Social Applications DC-2008 will explore conceptual and practical issues in the development and deployment of semantic and social applications to meet the needs of specific communities of practice. Edited by Jane Greenberg and Wolfgang Klas DC-2008 -

Using RSS to Spread Your Blog

10_588486 ch04.qxd 3/4/05 11:33 AM Page 67 Chapter 4 Using RSS to Spread Your Blog In This Chapter ᮣ Understanding just what a blog is ᮣ Creating the blog and the feed ᮣ Using your RSS reader ᮣ Creating a blog using HTML ᮣ Maintaining your blog ᮣ Publicizing your blog with RSS hat’s a blog, after all? Blog, short for Web log, is just a Web site with Wa series of dated entries, with the most recent entry on top. Those entries can contain any type of content you want. Blogs typically include links to other sites and online articles with the blogger’s reactions and com- ments, but many blogs simply contain the blogger’s own ramblings. Unquestionably, the popularity of blogging has fueled the expansion of RSS feeds. According to Technorati, a company that offers a search engine for blogs in addition to market research services, about one-third of blogs have RSS feeds. Some people who maintain blogs are publishing an RSS feed with- out even knowing about it, because some of the blog Web sites automatically create feeds (more about how this happens shortly). If you think that blogs are only personal affairs, remember that Microsoft has hundreds of them, and businesses are using them more and more to keep employees, colleagues, and customersCOPYRIGHTED up to date. MATERIAL In this chapter, I give a quick overview of blogging and how to use RSS with your blog to gain more readers. If you want to start a blog, this chapter explains where to go next. -

Introduction to Web 2.0 Technologies

Introduction to Web 2.0 Joshua Stern, Ph.D. Introduction to Web 2.0 Technologies What is Web 2.0? Æ A simple explanation of Web 2.0 (3 minute video): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0LzQIUANnHc&feature=related Æ A complex explanation of Web 2.0 (5 minute video): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nsa5ZTRJQ5w&feature=related Æ An interesting, fast-paced video about Web.2.0 (4:30 minute video): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NLlGopyXT_g Web 2.0 is a term that describes the changing trends in the use of World Wide Web technology and Web design that aim to enhance creativity, secure information sharing, increase collaboration, and improve the functionality of the Web as we know it (Web 1.0). These have led to the development and evolution of Web-based communities and hosted services, such as social-networking sites (i.e. Facebook, MySpace), video sharing sites (i.e. YouTube), wikis, blogs, etc. Although the term suggests a new version of the World Wide Web, it does not refer to any actual change in technical specifications, but rather to changes in the ways software developers and end- users utilize the Web. Web 2.0 is a catch-all term used to describe a variety of developments on the Web and a perceived shift in the way it is used. This shift can be characterized as the evolution of Web use from passive consumption of content to more active participation, creation and sharing. Web 2.0 Websites allow users to do more than just retrieve information. -

Blogging Glossary

Blogging Glossary Glossary: General Terms Atom: A popular feed format developed as an alternative to RSS. Autocasting: Automated form of podcasting that allows bloggers and blog readers to generate audio versions of text blogs from RSS feeds. Audioblog: A blog where the posts consist mainly of voice recordings sent by mobile phone, sometimes with some short text message added for metadata purposes. (cf. podcasting) Blawg: A law blog. Bleg: An entry in a blog requesting information or contributions. Blog Carnival: A blog article that contains links to other articles covering a specific topic. Most blog carnivals are hosted by a rotating list of frequent contributors to the carnival, and serve to both generate new posts by contributors and highlight new bloggers posting matter in that subject area. Blog client: (weblog client) is software to manage (post, edit) blogs from operating system with no need to launch a web browser. A typical blog client has an editor, a spell-checker and a few more options that simplify content creation and editing. Blog publishing service: A software which is used to create the blog. Some of the most popular are WordPress, Blogger, TypePad, Movable Type and Joomla. Blogger: Person who runs a blog. Also blogger.com, a popular blog hosting web site. Rarely: weblogger. Blogirl: A female blogger Bloggernacle: Blogs written by and for Mormons (a portmanteau of "blog" and "Tabernacle"). Generally refers to faithful Mormon bloggers and sometimes refers to a specific grouping of faithful Mormon bloggers. Bloggies: One of the most popular blog awards. Blogroll: A list of other blogs that a blogger might recommend by providing links to them (usually in a sidebar list). -

Between Ontologies and Folksonomies

BOF Between Ontologies and Folksonomies Michigan State University-Mi, US June 28, 2007 Workshop held in conjunction with Preface Today on-line communities, as well as individuals, produce a substantial amount of unstructured (and extemporaneous) content, arising from tacit and explicit knowledge sharing. Various approaches, both in the managerial and computer science fields, are seek- ing ways to crystallize the - somewhat volatile, but often highly valuable - knowl- edge contained in communities "chatters". Among those approaches, the most relevants appear to be those aimed at developing and formalizing agreed-upon semantic representations of specific knowledge domains (i.e. domain ontologies). Nonetheless, the intrinsic limits of technologies underpinning such approaches tend to push communities members towards the spontaneous adoption of less cumbersome tools, usually offered in the framework of the Web 2.0 (e.g. folkso- nomies, XML-based tagging, etc.), for sharing and retrieving knowledge. Inside this landscape, community members should be able to access and browse community knowledge transparently and in a personalized way, through tools that should be at once device-independent and context- and user-dependent, in order to manage and classify content for heterogeneous interaction channels (wired/wireless network workstations, smart-phones, PDA, and pagers) and dispa- rate situations (while driving, in a meeting, on campus). The BOF- Between Ontologies and Folksonomies workshop, held in conjunction with the third Communities and Technologies conference in June 2007 1, aimed at the development of a common understanding of the frontier technologies for shar- ing knowledge in communities. We are proposing here a selection of conceptual considerations, technical issues and "real-life case studies" presented during the workshop. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Leveraging Program Commonalities and Variations for Systematic Software Development and Maintenance Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/25z5n0t6 Author Zhang, Tianyi Publication Date 2019 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Leveraging Program Commonalities and Variations for Systematic Software Development and Maintenance A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science by Tianyi Zhang 2019 c Copyright by Tianyi Zhang 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Leveraging Program Commonalities and Variations for Systematic Software Development and Maintenance by Tianyi Zhang Doctor of Philosophy in Computer Science University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Miryung Kim, Chair Software is becoming increasingly pervasive and complex. During software development and maintenance, developers often make ad hoc decisions based on local program contexts and their own experience only, which may increase technical debt and raise unknown conse- quences as software evolves. This dissertation explores several opportunities to guide software development and maintenance by exploiting and visualizing the commonalities and varia- tions among similar programs. Our hypothesis is that unveiling what has and has not been done in other similar program contexts can help developers make more systematic decisions, explore implementation alternatives, and reduce the risk of unknown consequences. The inherent repetitiveness in software systems provides a solid foundation for identify- ing and exploiting similar code. This dissertation first presents two approaches that leverage the syntactic similarity and repetitiveness in local codebases to improve code reviews and software testing. -

Overview of the TREC-2007 Blog Track

Overview of the TREC-2007 Blog Track Craig Macdonald, Iadh Ounis Ian Soboroff University of Glasgow NIST Glasgow, UK Gaithersburg, MD, USA {craigm,ounis}@dcs.gla.ac.uk [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION The number of permalink documents in the collection is over The goal of the Blog track is to explore the information seeking 3.2 million, while the number of feeds is over 100,000 blogs. The behaviour in the blogosphere. It aims to create the required in- permalink documents are used as a retrieval unit for the opinion frastructure to facilitate research into the blogosphere and to study finding task and its associated polarity subtask. For the blog distil- retrieval from blogs and other related applied tasks. The track was lation task, the feed documents are used as the retrieval unit. The introduced in 2006 with a main opinion finding task and an open collection has been distributed by the University of Glasgow since task, which allowed participants the opportunity to influence the March 2006. Further information on the collection and how it was determination of a suitable second task for 2007 on other aspects created can be found in [1]. of blogs besides their opinionated nature. As a result, we have created the first blog test collection, namely the TREC Blog06 3. OPINION FINDING TASK collection, for adhoc retrieval and opinion finding. Further back- Many blogs are created by their authors as a mechanism for self- ground information on the Blog track can be found in the 2006 expression. Extremely-accessible blog software has facilitated the track overview [2]. -

8.5.512 Speechminer UI User Manual

SpeechMiner UI User Manual 8.5.5 Date: 7/11/2018 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction to SpeechMiner 1 New in this Release 4 SpeechMiner Deployments 15 Topics, Categories and Programs 17 Topics 19 Categories 21 Programs 23 Log into SpeechMiner 26 SpeechMiner Menu Reference 28 Chapter 2: Dashboard 30 Dashboard Menu Reference 31 Create a New Dashboard 32 Working with Dashboards 34 Widgets 36 Working with Widgets 37 Report Widget 40 My Messages Widget 43 Chapter 3: Explore 46 Explore Menu Reference 47 Search Results Grid 48 Working with the Search Results Grid 52 What is an Interaction? 55 Screen Recordings 58 Batch Actions 59 Create a New Search 64 Search Filter 66 Explore Terms 74 Saved Searches 75 Compare Saved Searches 77 Interaction Lists 79 Content Browser 82 Trending 84 Create a Trending Filter 86 Create a Custom Trending Cluster Task 88 Trending Filter Toolbar Description 91 Trending Chart Tool Tip Description 95 Trending Chart Data Description 97 Manage the Blacklist 101 Working with Saved Trending Filters 103 Export Trending Data 107 Chapter 4: Media Player 108 Playback 110 Playback Controls 111 Hidden Confidential Information 115 Dual-Channel Audio 116 Interaction Transcript 117 Interaction Comments 121 Interaction Events 124 Interaction Attributes 126 Media Player Options 127 Chapter 5: Reports 131 Reports Menu Reference 132 Create a New Report 133 Edit a Report 134 Run a Report 135 Analyze Report Data 137 Drill Down a Report 138 Working with Saved Reports 139 Schedule a Report 142 Report Templates 147 Report Template Layout -

Elements of MLA Citations

In English and in some humanities classes, you may be asked to use the MLA (Modern Language Association) system for documenting sources. The guidelines in this booklet follow those set forth in the MLA Handbook, 8th edition (2016). Rather than thinking of these guidelines simply as rules to be followed, we invite you to think of them as guidelines for partici pating in an academic community — a community in which the exchange of and extension of ideas requires a system. Even though the new guidelines present a system for citing many different kinds of sources, they don’t cover everything; and at times you will find that you have to think critically to adapt the guidelines to the source you are using. Elements of MLA citations MLA documentation consists of in-text citations that refer to a list of works cited at the end of a project. There are often several possible ways to cite a source in the list of works cited. Think care fully about your context for using the source so you can identify the pieces of information that you should include and any other information that might be helpful to your readers. The first step is to identify elements that are commonly found in works that writers cite. Author and title The first two elements, both of which are needed for many sources, are the author’s name and the title of the work. Each of these ele ments is followed by a period. Author. Title. 1 02_HAC_08268_01_42.indd 1 20/05/16 4:55 PM 2 Elements of MLA citations Container The next step is to identify elements of what MLA calls the “con tainer” for the work—any larger work that contains the source you are citing. -

![Arxiv:1810.03067V1 [Cs.IR] 7 Oct 2018](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1412/arxiv-1810-03067v1-cs-ir-7-oct-2018-1771412.webp)

Arxiv:1810.03067V1 [Cs.IR] 7 Oct 2018

Geocoding Without Geotags: A Text-based Approach for reddit Keith Harrigian Warner Media Applied Analytics Boston, MA [email protected] Abstract that will require more thorough informed consent processes (Kho et al., 2009; European Commis- In this paper, we introduce the first geolocation sion, 2018). inference approach for reddit, a social media While some social platforms have previously platform where user pseudonymity has thus far made supervised demographic inference dif- approached the challenge of balancing data access ficult to implement and validate. In particu- and privacy by offering users the ability to share lar, we design a text-based heuristic schema to and explicitly control public access to sensitive at- generate ground truth location labels for red- tributes, others have opted not to collect sensitive dit users in the absence of explicitly geotagged attribute data altogether. The social news website data. After evaluating the accuracy of our la- reddit is perhaps the largest platform in the lat- beling procedure, we train and test several ge- ter group; as of January 2018, it was the 5th most olocation inference models across our reddit visited website in the United States and 6th most data set and three benchmark Twitter geoloca- tion data sets. Ultimately, we show that ge- visited website globally (Alexa, 2018). Unlike olocation models trained and applied on the real-name social media platforms such as Face- same domain substantially outperform models book, reddit operates as a pseudonymous website, attempting to transfer training data across do- with the only requirement for participation being mains, even more so on reddit where platform- a screen name. -

Blogging for Engines

BLOGGING FOR ENGINES Blogs under the Influence of Software-Engine Relations Name: Anne Helmond Student number: 0449458 E-mail: [email protected] Blog: http://www.annehelmond.nl Date: January 28, 2008 Supervisor: Geert Lovink Secondary reader: Richard Rogers Institution: University of Amsterdam Department: Media Studies (New Media) Keywords Blog Software, Blog Engines, Blogosphere, Software Studies, WordPress Summary This thesis proposes to add the study of software-engine relations to the emerging field of software studies, which may open up a new avenue in the field by accounting for the increasing entanglement of the engines with software thus further shaping the field. The increasingly symbiotic relationship between the blogger, blog software and blog engines needs to be addressed in order to be able to describe a current account of blogging. The daily blogging routine shows that it is undesirable to exclude the engines from research on the phenomenon of blogs. The practice of blogging cannot be isolated from the software blogs are created with and the engines that index blogs and construct a searchable blogosphere. The software-engine relations should be studied together as they are co-constructed. In order to describe the software-engine relations the most prevailing standalone blog software, WordPress, has been used for a period of over seventeen months. By looking into the underlying standards and protocols of the canonical features of the blog it becomes clear how the blog software disperses and syndicates the blog and connects it to the engines. Blog standards have also enable the engines to construct a blogosphere in which the bloggers are subject to a software-engine regime. -

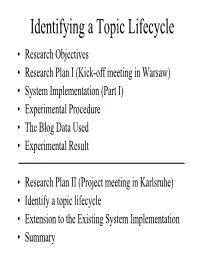

The Visualisation of Topic Spreading Between

Identifying a Topic Lifecycle • Research Objectives • Research Plan I (Kick-off meeting in Warsaw) • System Implementation (Part I) • Experimental Procedure • The Blog Data Used • Experimental Result • Research Plan II (Project meeting in Karlsruhe) • Identify a topic lifecycle • Extension to the Existing System Implementation •Summary Research Objectives • Identify emerging topics about public science debates (topic identification), such as GM foods and foot-and-mouth disease; • Keep track of the flow/spreading of the emerging topics (topic tracking). Research Plan I • Extract a set of terms from a collection of texts. • Apply a technique to select a set of significant terms which may represent emerging topics about science debates. • Group the significant terms into a number of blogs. System Implementation (Part I) RSS Monitor POS Tagger + NP Chunker Text Extractor Inverted Significant Blog List File Builder Term Selector Creator Blog data A collection A collection of Inverted A set of A blog in XML of texts chunked texts files significant node list terms Experimental Procedure • Apply three term selection methods independently, in order to select a set of significant terms on a certain date. These are chi-square statistics, mutual information and information gain. – Build 2x2 contingency table, so that chi-square and mutual information values can be computed. – Build a table which stores the entropy value of each date, so that information gain can be computed • Select a number of topics manually as a starting point. • Select a number