District With

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CDF Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2004-14-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. SAM HINGA NORMAN MOININA FOFANA ALLIEU KONDEWA WEDNESDAY, 22 FEBRUARY 2006 9.40 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER I Before the Judges: Pierre Boutet, Presiding Bankole Thompson Benjamin Mutanga Itoe For Chambers: Ms Roza Salibekova Ms Anna Matas For the Registry: Mr Geoff Walker For the Prosecution: Mr Desmond De Silva Mr Kevin Tavener Mr Joseph Kamara Ms Bianca Suciu (Case Manager) For the Principal Defender: NO APPEARANCE For the accused Sam Hinga Dr Bu-Buakei Jabbi Norman: Mr Alusine Sesay Ms Claire da Silva (legal assistant) Mr Kingsley Belle (legal assistant) For the accused Moinina Fofana: Mr Arrow Bockarie Mr Andrew Ianuzzi For the accused Allieu Kondewa: Mr Ansu Lansana NORMAN ET AL Page 2 22 FEBRUARY 2006 OPEN SESSION 1 [CDF22FEB06A - CR] 2 Wednesday, 22 February 2006 3 [Open session] 4 [The accused present] 09:36:33 5 [Upon resuming at 9.40 a.m.] 6 WITNESS: LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARDS [Continued] 7 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning, Dr Jabbi. Good morning, 8 Mr Witness. Dr Jabbi, when we adjourned yesterday we were back 9 at you with re-examination, if any. You had indicated that you 09:40:46 10 did have some. 11 MR JABBI: Yes, My Lord. 12 PRESIDING JUDGE: Are you prepared to proceed now? 13 MR JABBI: Yes, My Lord. 14 PRESIDING JUDGE: Please do so. 09:40:59 15 RE-EXAMINED BY MR JABBI: 16 Q. Good morning, General. 17 A. Good morning. 18 Q. Just one or two points of clarification. -

The Constitution of Sierra Leone Act, 1991

CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT SUPPLEMENT TO THE SIERRA LEONE GAZETTE EXTRAORIDARY VOL. CXXXVIII, NO. 16 dated 18th April, 2007 CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT NO. 5 OF 2007 Published 18th April, 2007 THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991 (Act No. 6 of 1991) PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS (DECLARATION OF CONSTITUENCIES) Short tittle ORDER, 2007 In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by Subsection (1) of section 38 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991, the Electoral Commission hereby makes the following Order:- For the purpose of electing the ordinary Members of Parliament, Division of Sierra Leone Sierra Leone is hereby divided into one hundred and twelve into Constituencies. constituencies as described in the Schedule. 2 3 Name and Code Description SCHEDULE of Constituency EASTERN REGION KAILAHUN DISTRICT Kailahun This Constituency comprises of the whole of upper Bambara and District part of Luawa Chiefdom with the following sections; Gao, Giehun, Costituency DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCIES 2 Lower Kpombali and Mende Buima. Name and Code Description of Constituency (NEC The constituency boundary starts in the northwest where the Chiefdom Const. 002) boundaries of Kpeje Bongre, Luawa and Upper Bambara meet. It follows the northern section boundary of Mende Buima and Giehun, then This constituency comprises of part of Luawa Chiefdom southwestern boundary of Upper Kpombali to meet the Guinea with the following sections: Baoma, Gbela, Luawa boundary. It follows the boundary southwestwards and south to where Foguiya, Mano-Sewallu, Mofindo, and Upper Kpombali. the Dea and Upper Bambara Chiefdom boundaries meet. It continues along the southern boundary of Upper Bambara west to the Chiefdom (NEC Const. The constituency boundary starts along the Guinea/ Sierra Leone boundaries of Kpeje Bongre and Mandu. -

Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone

Working paper Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone Daron Acemoglu Tristan Reed James A. Robinson September 2013 When citing this paper, please use the title and the following reference number: S-2012-SLE-1 Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone⇤ Daron Acemoglu† Tristan Reed ‡ James A. Robinson§ September 26, 2013 Abstract We use the colonial organization of chieftaincy in Sierra Leone to study the e↵ect of con- straints on chiefs’ power on economic outcomes, citizens’ attitudes and social capital. A paramount chief must come from one of the ruling families originally recognized by British colonial authorities. Chiefs face fewer constraints and less political competition in chiefdoms with fewer ruling families. We show that places with fewer ruling families have significantly worse development outcomes today—in particular, lower rates of educational attainment, child health, non-agricultural employment and asset ownership. We present evidence that variation in the security of property rights in land is a potential mechanism. Paradoxically we also show that in chiefdoms with fewer ruling families the institutions of chiefs’ authority are more highly respected among villagers, and measured social capital is higher. We argue that these results reflect the capture of civil society organizations by chiefs. JEL Classification: D72, O12, N27 Keywords: Economic Development, Elite Control, Political Economy, Social Capital. ⇤We thank Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. Bangura, Mohammed Bangura, Lyttleton Braima, Shaka Kamara, Solomon Kamara, Bai Santigie Kanu, Salieu Mansaray, Michael Sevalie, Alusine M. Tarawalie, and David J. Walters for their work in collecting the data on the histories of chieftaincies and ruling families. -

Sierra Leone

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SIERRA LEONE Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 7 July, 2001) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 788 80 85 Fax: + 41 22 788 80 86 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 10 ACCESS TO UN HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORTS 10 HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORTS BY THE UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS (22 DECEMBER 2000 – 16 JUNE 2001) 10 MAIN CAUSES FOR DISPLACEMENT 10 COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT CAUSED BY MORE THAN NINE YEARS OF WIDESPREAD CONFLICT- RELATED HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES (1991- 2000) 10 MAJOR NEW DISPLACEMENT AFTER BREAK DOWN OF THE PEACE PROCESS IN MAY 2000 12 NEW DISPLACEMENT AS CONFLICT EXTENDED ACROSS THE GUINEA-SIERRA LEONE BORDER (SEPTEMBER 2000 – MAY 2001) 15 BACKGROUND OF THE CONFLICT 18 HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF CONFLICT (1991-1998) 18 ESCALATED CONFLICT DURING FIRST HALF OF 1999 CAUSED SUBSTANTIAL DISPLACEMENT 21 CONTINUED CONFLICT DESPITE THE SIGNING OF THE LOME PEACE AGREEMENT (JULY 1999-MAY 2000) 22 PEACE PROCESS DERAILED AS SECURITY SITUATION WORSENED DRAMATICALLY IN MAY 2000 25 -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS % This reproduction is the best copy available. THE CONTRIBVTION OF TRADITIONAL SCHOOLING TO THE EDUCATION OF TBE ARTIST IN SIERRA LEONE Caesar Amandus Malcolm Coker A Thesis in The Department of Art Education Presented in Partial hrlfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada O Caesar Amandus Malcolm Coker, 2001 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. me Wellington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence dowing the exdusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de rnicrofiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fomat électronique. The author retauis ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT THE CONTRIBUTION OF TRADITIONAL SCHOOLING TO THE EDUCATION OF TBE ARTXST TN SIERRA LEONE Caesar Amandus Malcolm Coker, Ph-D. Concordia University, 2 00 1 This study focuses on the education and work of indigenous Sierra Leonean visual artists . -

Local Government and Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: a Concise Introduction

Local Government and Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: A Concise Introduction P. C. Gbawuru Mansaray III (alias Pagay) P. C. Alimamy Lahai Mansaray V Dembelia Sinkunia Chiefdom P. C. Madam Doris Lenga-Caulker P. C. Henry Fangawa of Gbabiyor II of Kagboro Chiefdom, Wandor Chiefdom, Falla Shenge (Moyamba District), (Kenema District), P. C. Theresa Vibbi III. of Kandu Leppiama, Gbadu Levuma (Kenema District) M. N. Conteh Revised Edition 2019 Local Government and Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: A Concise Introduction A cross-section of Paramount Chiefs of Sierra Leone displaying their new staffs M. N. Conteh Revised Edition 2019 Table of Contents Page Contents i Acronyms ii Preface and acknowledgements iii About the Author v Chapter 1. 1 Local Government in Sierra Leone Chapter 2. 38 Paramount Chieftaincy in Sierra Leone: an introduction to its history and Electoral Process. Chapter 3. 80 Appendices Appendix 1: List of Chiefdoms and their Ruling Houses 82 Appendix 2: NEC Form PC 3 – statutory Declaration of Rights for 103 PC elections Appendix 3: List of symbols for PC elections (and Independent 105 candidates for Local Councils). Appendix 4: Joint Reporting Format for PC elections 107 Appendix 5 and 6: Single and multi-member wards for District 111 Councils. Appendix 7 Nomination Form for Local Council Candidate 114 References and Suggested books for further reading 1 16 i Acronyms APC – All Peoples’ Congress CC – Chiefdom Council / Chiefdom Committee DC – District Commissioner /District Council DEO – District Electoral Officer -

Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone Author(S): Daron Acemoglu, Tristan Reed, and James A

Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone Author(s): Daron Acemoglu, Tristan Reed, and James A. Robinson Source: Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 122, No. 2 (April 2014), pp. 319-368 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/674988 . Accessed: 24/05/2014 13:19 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Political Economy. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 140.247.116.217 on Sat, 24 May 2014 13:19:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Chiefs: Economic Development and Elite Control of Civil Society in Sierra Leone Daron Acemoglu Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research Tristan Reed Harvard University James A. Robinson Harvard University and the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research We study the effect of constraints on chiefs’ power on economic out- comes, citizens’ attitudes, and social capital. A paramount chief in Si- erra Leone must come from a ruling family originally recognized by British colonial authorities. -

![[NEC] – 2017 FINAL LIST of VOTER REGISTRATION CENTRES Region](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3710/nec-2017-final-list-of-voter-registration-centres-region-4843710.webp)

[NEC] – 2017 FINAL LIST of VOTER REGISTRATION CENTRES Region

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSI ON [NEC] – 2017 FINAL LIST OF VOTER REGISTRATION CENTRES Region District Constituency Ward Centre Code CentreName Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1001 Town Barray,Kamakpodu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1002 Town Barray, Falama Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1003 Town Barray, Dambar Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1004 Sandia Community Barray, Sandia Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1005 Town Barray, Taidu Eastern Kailahun 1 1 1006 Open Space, Killima Town Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1007 NA court Barray, Buedu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1008 Buedu Community Centre, Buedu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1009 R.C Primary School, Buedu Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1010 KLDEC, Weh Town Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1011 Open Space, Mendekuama Town Eastern Kailahun 1 2 1012 Town Barray, Koldu Bendu Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1013 Court Barray , Tongi tingi, Dawa Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1014 Town Barray, Tongi tingi, Vuahun Town Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1015 Court Barray, Tongi tingi, Mandopolahun Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1016 Town Barray, Damballu Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1017 Mano Town Barray, M.Tingi Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1018 Town Barray, Benduma Town Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1019 Town Barray, Kamadu Town Eastern Kailahun 1 3 1020 Town Barray, Gbalama Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1021 Town Barray, Lela, Fowa Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1022 Gbahama Town, Lela Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1023 Court Barray, Kangama Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1024 KLDEC School, Kangama Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1025 Open Space, Yenlendu Town Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1026 Town Barray, Tangabu Eastern Kailahun 2 4 1027 History Ministry Church Kpekeledu Town Eastern -

PAYMENT of TUITION FEES to PRE-PRIMARY SCHOOLS in KENEMA DISTRICT for SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount No

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRE-PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN KENEMA DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount No. EMIS Name Of School District Chiefdom Address Headcount Total Amount Per Child Kenema 1 129102115 Assurance Pre-School Nongowa Show Avenue 83 10,000 830,000 District Kenema 2 129102106 Good Shephered Pre-School Nongowa Nyandeyama 251 10,000 2,510,000 District Kenema 3 129103106 Holy Family Pre-School Nongowa Blama Road 172 10,000 1,720,000 District Kenema 4 121402101 Holy Rosary Pre-School Small-Bo Blama 82 10,000 820,000 District Kenema NONGOW 5 129102232 Integrated Community Pre-School Blama Road 107 10,000 1,070,000 District A CITY Kenema 6 129103107 Jefferson Baptist Pre-School Nongowa Lango Town 11 10,000 110,000 District Kenema 7 129103101 Jos Marian Pre-School Nongowa Panderu 15 10,000 150,000 District Kenema 8 121601101 Kenema District Education Committee Pre- Schoool Wandor Baama 46 10,000 460,000 District Kenema NONGOW 9 121209138 Kenema District Education Committee Pre-School Hanga 121 10,000 1,210,000 District A Kenema NONGOW 10 129102112 Masroor Ahmadiyya Pre-School Fonikor 98 10,000 980,000 District A CITY Kenema NONGOW 11 121202101 Methodist Pre-School Baion Street 72 10,000 720,000 District A CITY Kenema 12 129102101 National Islamic Pre-School NIAWA Bandawor 142 10,000 1,420,000 District Kenema 13 129102104 Provencial Pre-School Nongowa Kondebotihun 143 10,000 1,430,000 District Kenema Dr. Demby 14 121202105 Ridwan Pre-School Nongowa 124 10,000 1,240,000 District Street Kenema 15 120601101 Roman Catholic -

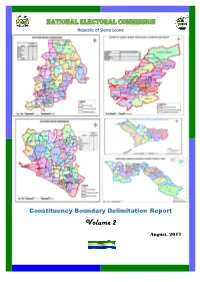

2017 Constituency Boundary Delimitation Report, Vol. 2

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Republic of Sierra Leone Constituency Boundary Delimitation Report Volume 2 August, 2017 Foreword The National Electoral Commission (NEC) is submitting this report on the delimitation of constituency and ward boundaries in adherence to its constitutional mandate to delimit electoral constituency and ward boundaries, to be done “not less than five years and not more than seven years”; and complying with the timeline as stipulated in the NEC Electoral Calendar (2015-2019). The report is subject to Parliamentary approval, as enshrined in the 1991 Constitution of Sierra Leone (Act No 6 of 1991); which inter alia states delimitation of electoral boundaries to be done by NEC, while Section 38 (1) empowers the Commission to divide the country into constituencies for the purpose of electing Members of Parliament (MPs) using Single Member First- Past –the Post (FPTP) system. The Local Government Act of 2004, Part 1 –preliminary, assigns the task of drawing wards to NEC; while the Public Elections Act, 2012 (Section 14, sub-sections 1 &2) forms the legal basis for the allocation of council seats and delimitation of wards in Sierra Leone. The Commission appreciates the level of technical assistance, collaboration and cooperation it received from Statistics Sierra Leone (SSL), the Boundary Delimitation Technical Committee (BDTC), the Boundary Delimitation Monitoring Committee (BDMC), donor partners, line Ministries, Departments and Agencies and other key actors in the boundary delimitation exercise. The hiring of a Consultant, Dr Lisa Handley, an internationally renowned Boundary delimitation expert, added credence and credibility to the process as she provided professional advice which assisted in maintaining international standards and best practices. -

Downloaded Cc-By-Nc from License.Brill.Com09/29/2021 02:25:30AM Via Free Access

chapter 4 Fragmentation and the Temne: From War Raids into Ethnic Civil Wars The Temne and Their Neighbours: A Long-Standing Scenario of Inter-ethnic Hostilities? The former British colony of Sierra Leone is today regarded as one of the classic cases of a society that is politically polarised by ethnic antagonism. By the 1950s, the decade before independence, ethnic fault lines had an impact on local political life and the inhabitants of the colony appeared to practise ethnic voting. Both the Sierra Leone People’s Party (slpp) government formed after 1957, led by Milton Margai, and the All People’s Congress (apc) government of Siaka Stevens coming to power in 1967/68, relied on ethnic support and cre- ated ethnic networks: the slpp appeared to be ‘southern’ and ‘eastern’, and Mende-dominated, the apc ‘northern’ and Temne-led.1 Between 1961 and the 1990s, such voting behaviour can be found in sociological and political science survey data.2 However, the period of brutal civil war in the 1990s weakened some of these community links, as local communities were more interested in their survival than in ethnic solidarities.3 We have seen that the 2007 legislative elections contradicted this apparent trend. Before the second half of the nineteenth century, the territory of present-day Sierra Leone was politically fragmented into a number of different small structures, which were often much smaller than the pre-colonial states of Senegambia (Map 4). The only regional exception was the ‘federation’ of Morea, which, however, was an unstable entity. The slave trade and the ‘legitimate commerce’ in palm 1 Cartwright, John R., Politics in Sierra Leone 1947–67 (Toronto – Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 1970), 101–2, 128; Fisher, ‘Elections’, 621–3; Riddell, J.