List of Sierra Leone Women Chiefs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sierra Leone

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.B / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

Eastern Province

SIERRA LEONE EASTERN PROVINCE afi B or B a fi n Guinea Guinea KOINADUGU KAMBIA BOMBALI ! PORT LOKO KONO Fandaa TONKOLILI 5 ! Henekuma WESTERN AREA ! Dunamor ! ! Powma KAILAHUN Fintibaya ! Siakoro MOYAMBA BO ! Konkonia ! Kondewakor Kongowakor !! KENEMA ! ! Saikuya ! M!okeni K! ongoadu Bongema II ! Poteya ! ! ! T o l i ! Komandor T o l i Kombodu ! ! ! ! ! ! Kondeya Fabandu Foakor ! !! BONTHE Thomasidu Yayima Fanema ! Totor ! !! Bendu Leimaradu ! ! ! Foindu ! ! Gbolia PUJEHUN !!Feikaya Sakamadu ! ! Wasaya! Liberia Bayawaindu ! Bawadu Jongadu Sowadu ! Atlantic Ocean Norway Bettydu ! ! Kawamah Sandia! ! ! ! ! ! Kamindo ! !! ! ! Makongodu ! Sam! adu Bondondor ! ! Teiya ! ! ! ! Wonia ! Tombodu n Primary School ! ! e wordu D Wordu C Heremakonoh !! ! !! ! Yendio-Bengu ! d !! Kwafoni n ! !Dandu Bumanja !Kemodu ! ! e ! Yaryah B Yuyah Mor!ikpandidu ! ! S ! ! ! ! ! Kondeya II ! r ! ! ! ! !! Kindia o ! ! Deiyor! II Pengidu a Makadu Fosayma Bumbeh ! ! an Kabaidu ! Chimandu ! ! ! Yaryah A ! Kondeya Kongofinkor Kondeya Primary School ! Sambaia p ! ! ! F!aindu m Budu I !! Fodaydu ! ! Bongema I a !Yondadu !Kocheo ! Kwakoima ! Gbandu P Foimangadu Somoya ! ! Budu II ! ! ! Koyah ! Health Centre Kamba ! ! Kunundu Wasaya ! ! ! ! Teidu ! Seidu Kondeya 1 ! ! Kayima A ! Sandema! ! ! suma II suma I Primary School ! ! ! ! Kayima B Koidundae !!! R.C. Primary School ! ! ! !! Wokoro UMC Primary School !! Sangbandor Tankoro ! ! Mafidu ! Dugbema ! Piyamanday ! Suma I Bendu ! Kayima D ! ! Kwikuma Gbeyeah B ! Farma Bongema ! Koekuma ! Gboadah ! ! ! ! Masaia ! Gbaiima Kombasandidu -

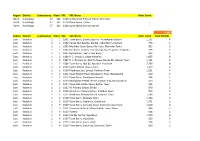

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North Koinadugu 47 162 6169 Al-Harrakan Primary School, Woredala - North Koinadugu 47 162 6179 Open Space 2,Kabo - North Koinadugu 47 162 6180 Open Space, Kamayortortor - 9,493 Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count Total PS(100) East Kailahun 1 1 1001 Town Barry, Baoma, Baoma - Kunywahun Section 1,192 4 East Kailahun 1 1 1002 Palava Hut, Baoma, Baoma - Gborgborma Section 478 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1003 Mofindor Court Barry, Mofindor, Mofindor Town 835 3 East Kailahun 1 1 1004 Methodist primary school yengema, Yengama, Yengema 629 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1005 Nyanyahun Town, Town Barry 449 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1006 R. C. School 1, Upper Masanta 1,855 6 East Kailahun 1 2 1007 R. C. Primary 11, Gbomo Town, Buedu RD, Gbomo Town 1,121 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1008 Town Barry, Ngitibu, Ngitibu 1-Kailahum 2,209 8 East Kailahun 1 2 1009 KLDEC School, new London 1,259 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1010 Methodist Sec. School, Kailahun Town 1,031 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1011 Town Market Place, Bandajuma Town, Bandajuma 640 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1012 Town Barry, Bandajuma Sinneh 294 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1013 Bandajuma Health Centre, Luawa Foiya, Bandajuma Si 473 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1014 Town Hall, Borbu-Town, Borbu- Town 315 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1015 RC Primary School, Borbu 870 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1016 Amadiyya Primary School, Kailahun Town 973 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1017 Methodist Primary School, kailahun Town 1,266 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1018 Town Barry, Sandialu Town 1,260 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1019 Town -

CDF Trial Transcript

Case No. SCSL-2004-14-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. SAM HINGA NORMAN MOININA FOFANA ALLIEU KONDEWA WEDNESDAY, 22 FEBRUARY 2006 9.40 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER I Before the Judges: Pierre Boutet, Presiding Bankole Thompson Benjamin Mutanga Itoe For Chambers: Ms Roza Salibekova Ms Anna Matas For the Registry: Mr Geoff Walker For the Prosecution: Mr Desmond De Silva Mr Kevin Tavener Mr Joseph Kamara Ms Bianca Suciu (Case Manager) For the Principal Defender: NO APPEARANCE For the accused Sam Hinga Dr Bu-Buakei Jabbi Norman: Mr Alusine Sesay Ms Claire da Silva (legal assistant) Mr Kingsley Belle (legal assistant) For the accused Moinina Fofana: Mr Arrow Bockarie Mr Andrew Ianuzzi For the accused Allieu Kondewa: Mr Ansu Lansana NORMAN ET AL Page 2 22 FEBRUARY 2006 OPEN SESSION 1 [CDF22FEB06A - CR] 2 Wednesday, 22 February 2006 3 [Open session] 4 [The accused present] 09:36:33 5 [Upon resuming at 9.40 a.m.] 6 WITNESS: LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARDS [Continued] 7 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning, Dr Jabbi. Good morning, 8 Mr Witness. Dr Jabbi, when we adjourned yesterday we were back 9 at you with re-examination, if any. You had indicated that you 09:40:46 10 did have some. 11 MR JABBI: Yes, My Lord. 12 PRESIDING JUDGE: Are you prepared to proceed now? 13 MR JABBI: Yes, My Lord. 14 PRESIDING JUDGE: Please do so. 09:40:59 15 RE-EXAMINED BY MR JABBI: 16 Q. Good morning, General. 17 A. Good morning. 18 Q. Just one or two points of clarification. -

Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Main objectives • In collaboration with the Government of Sierra Leone and other partners, pursue the reinte- gration of Sierra Leonean returnees, leading to • Provide international protection and basic a complete phase-out of interventions by humanitarian assistance to Liberian refugees. UNHCR (i.e. rebuild national protection struc- • Facilitate the repatriation of Liberian refugees tures and hand over assistance activities to who opt to return home in conditions of safety development actors). and dignity; provide information about security and living conditions in Liberia. Planning figures • Facilitate local integration, naturalization or Population Jan 2005 Dec 2005 resettlement for Liberian refugees who arrived in Sierra Leone during the 1990s and are not Liberia (refugees) 50,000 24,000 willing to repatriate. Sierra Leonean 30,000 0 • Enhance Government capacity to handle refugee returnees issues following the adoption and implementa- Total 80,000 24,000 tion of national refugee legislation, including assisting new government structures to become Total requirements: 25,043,136 operational. UNHCR Global Appeal 2005 174 the 4Rs strategy, has yielded positive results, with Working environment the presence of the UNDP/TST (Transitional Sup- port Team) being accommodated in UNHCR field Major developments offices to ensure continuity of interventions. With the focus of reintegration efforts on consolidating In 2004, political stability and the progressive res- and linking of work already undertaken to the toration of state authority permitted a further longer-term programmes of development actors, 30,000 Sierra Leoneans to return. By 31 July 2004 UNHCR will only fund new projects in 2005 if they – the end of the organized operation launched in are sure to reach completion by the year’s end. -

Humanist Watch Salone (Huwasal) 2012 Annual Report

HUMANIST WATCH SALONE (HUWASAL) 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 29 HUMONYA AVENUE KENEMA CITY KENEMA DISTRICT EASTERN PROVINCE OF SIERRA LEONE Email: [email protected] Contact phone Number(s): +232779075/+23276582937. P O Box 102 Kenema 2012 Annual Report on Humanist Watch Salone Activities Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENT ACKONWLEDGEMENT INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND OF HUMANIST WATCH SALONE ACCOMPLISHMENT GENDER EQUITY AND WOMEN EMPOWERMENT CHILD PROTECTION PROGRAMME HEALTH HUMAN RIGHTS AND GOOD GOVERNANCE YOUTH EMPOWERMENT AFFLILIATION SOURCES OF FUNDING LESSONS LEARNT/OUTCOMES CONCLUSION 2012 Annual Report on Humanist Watch Salone Activities Page 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We wish to extend thanks to our generous donor partners such as UNDP Access to Justice Programme, Amnesty International Sierra Leone, International Rescue Committee (IRC/GBV Programme), International Foundation for Election System (IFES) and Global Xchange/ VSO for both financial and technical support accorded to Humanist Watch Salone towards the implementation of its programme-projects in 2012. Moreover our sincere thanks and appreciation goes to our Advisory Board for providing support towards effective and efficient running of the day –to- day affairs of Humanist Watch Salone. Special and heartfelt thanks to our civil society partners and state actors and lastly, we extend a very big thanks to all our staff members for their restless effort behind the successes of our activities in 2012. 2012 Annual Report on Humanist Watch Salone Activities Page 3 Introduction and Background of Humanist Watch Salone Humanist Watch Salone (HUWASAL) is an indigenous human rights and development organization established in 2003 by a group of visionary and courageous human rights activists and development workers. The organization started as Community-Based organization and is now registered with Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED) as National Non- Governmental Organization. -

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Bo District for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN BO DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR Amount NO. EMIS Name Of School Region District Chiefdom Address Headcount Total to School Per Child 1 311301222 Abdul Tawab Haikal Primary School South BO District Tikonko Samie 610 10000 6,100,000 Bo Kenema 2 319103274 Agape Way Christian Primary School South BO District Kakua 380 10000 Highway 3,800,000 3 311401201 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Valunia Baomahun 822 10000 8,220,000 4 310702210 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Jaima Koribondo 341 10000 3,410,000 5 310202206 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Bagbo Levuma 203 10000 2,030,000 Bumpe 6 310502209 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Makayoni 215 10000 Ngao 2,150,000 7 311401218 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Valunia Mandu 221 10000 2,210,000 8 310201205 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Bagbo Momajoe 338 10000 3,380,000 Bumpe 9 310503217 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary South BO District Walihun 264 10000 Ngao 2,640,000 Baoma 10 310403210 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Baoma 122 10000 Gbandi 1,220,000 Kenema 11 311401209 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Valunia 330 10000 Blango 3,300,000 12 311001208 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Lugbu Kpatobu 244 10000 2,440,000 13 310702215 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Jaiama Kpetema 212 10000 2,120,000 14 310402205 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School South BO District Baoma Ndogbogoma 297 10000 2,970,000 15 310201211 Ahmadiyya -

G U I N E a Liberia Sierra Leone

The boundaries and names shown and the designations Mamou used on this map do not imply official endorsement or er acceptance by the United Nations. Nig K o L le n o G UINEA t l e a SIERRA Kindia LEONEFaranah Médina Dula Falaba Tabili ba o s a g Dubréka K n ie c o r M Musaia Gberia a c S Fotombu Coyah Bafodia t a e r G Kabala Banian Konta Fandié Kamakwie Koinadugu Bendugu Forécariah li Kukuna Kamalu Fadugu Se Bagbe r Madina e Bambaya g Jct. i ies NORTHERN N arc Sc Kurubonla e Karina tl it Mateboi Alikalia L Yombiro Kambia M Pendembu Bumbuna Batkanu a Bendugu b Rokupr o l e Binkolo M Mange Gbinti e Kortimaw Is. Kayima l Mambolo Makeni i Bendou Bodou Port Loko Magburaka Tefeya Yomadu Lunsar Koidu-Sefadu li Masingbi Koundou e a Lungi Pepel S n Int'l Airport or a Matotoka Yengema R el p ok m Freetown a Njaiama Ferry Masiaka Mile 91 P Njaiama- Wellington a Yele Sewafe Tongo Gandorhun o Hastings Yonibana Tungie M Koindu WESTERN Songo Bradford EAS T E R N AREA Waterloo Mongeri York Rotifunk Falla Bomi Kailahun Buedu a i Panguma Moyamba a Taiama Manowa Giehun Bauya T Boajibu Njala Dambara Pendembu Yawri Bendu Banana Is. Bay Mano Lago Bo Segbwema Daru Shenge Sembehun SOUTHE R N Gerihun Plantain Is. Sieromco Mokanje Kenema Tikonko Bumpe a Blama Gbangbatok Sew Tokpombu ro Kpetewoma o Sh Koribundu M erb Nitti ro River a o i Turtle Is. o M h Sumbuya a Sherbro I. -

Post-Ebola Community Health Worker Programme Performance In

F1000Research 2019, 8:794 Last updated: 28 SEP 2021 RESEARCH ARTICLE Post-Ebola Community Health Worker programme performance in Kenema District, Sierra Leone: A long way to go! [version 1; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations] Harold Thomas1, Katrina Hann 2, Mohamed Vandi1, Joseph Bengalie Sesay3, Koi Sylvester Alpha4, Robinah Najjemba 5 1Directorate of Health Security and Emergencies, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Freetown, Sierra Leone 2Sustainable Health Systems, Freetown, Sierra Leone 3Koinadugu District Health Management Team, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Kabala, Sierra Leone 4Kenema District Health Management Team, Ministry of Health and Sanitation, Kenema, Sierra Leone 5Makerere University School of Public Health, Makerere, Uganda v1 First published: 06 Jun 2019, 8:794 Open Peer Review https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18677.1 Latest published: 09 Apr 2020, 8:794 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.18677.2 Reviewer Status Invited Reviewers Abstract Background: The devastating 2014-2015 Ebola outbreak in Sierra 1 2 Leone could erode the gains of the health system including the Community Health Worker (CHW) programme. We conducted a study version 2 to ascertain if the positive trend in reporting cases of malaria, (revision) report pneumonia and diarrhoea treated by CHWs in the post-Ebola period 09 Apr 2020 has been sustained 18 months post-Ebola. Methods: We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study using version 1 aggregated CHW programme data (2013-2017) from all Primary 06 Jun 2019 report report Health Units in Kenema district. Data was extracted from the District Health Information System and analysed using STATA. Data in the pre- (June 2013-April 2014), during- (June 2014-April 2015) and post-Ebola 1. -

2016 School List.Xlsx

emis_num Level Region Council Chfdom School Name Town phone owner 110101101 PRESCHOOL EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT CENTRE BAIWALLA 076593767 COMMUNITY 110101201 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 METHODIST PRIMARY BAIWALA BAIWALA 78963548 MISSION 110101202 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 NATIONAL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL BAOMA 078624877 MISSION 110101203 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 PROVINCIAL ISLAMIC DODO PRIMARY SCHOOL DODO TOWN 078451705 MISSION 110101205 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY NAGBENA 078360004 MISSION 110101206 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL SIENGA SIENGA 076484775 MISSION KAILAHUN DISTRICT EDUCATION COUNCIL PRIMARY 110101207 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 TAKPOIMA 79175290 GOVERNMENT SCHOOL 110101208 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL BAIWALLA 76606361 MISSION 110101209 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 KAILAHUN DISTRICT EDUCATION COMMITTEE KURANKO KURANKO 76735861 GOVERNMENT 110101210 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL SAKIEMA 078456779 MISSION 110101211 PRIMARY EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 ROMAN CATHOLIC PRIMARY SCHOOL 076820424 MISSION 110101301 JSS EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 1 PEACE MEMORIAL JUNIOR SECONDARY SCHOOL BAIWALLA 78540707 GOVERNMENT 110201101 PRESCHOOL EAST KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL 2 SUPREME ISLAMIC PRE‐SCHOOL DARU 77702647 MISSION EARLY CHILDHOOD CARE AND DEVELOPMENT PRE‐ 110201102 -

Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

April 2008 NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume One February 2008 This page is intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Stages in the Ward Boundary Delimitation Process 7 Stage One: Establishment of methodology including drafting of regulations 7 Stage Two: Allocation of Local Councils seats to localities 13 Stage Three: Drawing of Boundaries 15 Stage Four: Sensitization of Stakeholders and General Public 16 Stage Five: Implement Ward Boundaries 17 Conclusion 18 APPENDICES A. Database for delimiting wards for the 2008 Local Council Elections 20 B. Methodology for delimiting ward boundaries using GIS technology 21 B1. Brief Explanation of Projection Methodology 22 C. Highest remainder allocation formula for apportioning seats to localities for the Local Council Elections 23 D. List of Tables Allocation of 475 Seats to 19 Local Councils using the highest remainder method 24 25% Population Deviation Range 26 Ward Numbering format 27 Summary Information on Wards 28 E. Local Council Ward Delimitation Maps showing: 81 (i) Wards and Population i (ii) Wards, Chiefdoms and sections EASTERN REGION 1. Kailahun District Council 81 2. Kenema City Council 83 3. Kenema District Council 85 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 87 5. Kono District Council 89 NORTHERN REGION 6. Makeni City Council 91 7. Bombali District Council 93 8. Kambia District Council 95 9. Koinadugu District Council 97 10. Port Loko District Council 99 11. Tonkolili District Council 101 SOUTHERN REGION 12. Bo City Council 103 13. Bo District Council 105 14. Bonthe Municipal Council 107 15. -

Sierra Leone Understanding Land Investment Deals in Africa

Understanding Land investment deaLs in africa Country report: sierra Leone Understanding Land investment deaLs in africa Country report: sierra Leone acknowLedgements This report was researched and written by Joan Baxter under the direction of Frederic Mousseau. Anuradha Mittal and Shepard Daniel also provided substantial editorial support. We are deeply grateful to Elke Schäfter of the Sierra Leonean NGO Green Scenery, and to Theophilus Gbenda, Chair of the Sierra Leone Association of Journalists for Mining and Extractives, for their immense support, hard work, and invaluable contributions to this study. We also want to thank all those who shared their time and information with the OI researchers in Sierra Leone. Special thanks to all those throughout the country who so generously assisted the team. Some have not been named to protect their identity, but their insights and candor were vital to this study. The Oakland Institute is grateful for the valuable support of its many individual and foundation donors who make our work possible. Thank you. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication, however, are those of the Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Design: amymade graphic design, [email protected], amymade.com Editors: Frederic Mousseau & Granate Sosnoff Production: Southpaw, Southpaw.org Photograph Credits © Joan Baxter Cover photo: Cleared land by the SLA project Publisher: The Oakland Institute is a policy think tank dedicated to advancing public participation and fair debate on critical social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2011 by The Oakland Institute The text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full.