Sthjeme Fourah Bay College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sierra Leone

EDITION 2010 VOLUME I.B / AFRICA DIRECTORY OF DEVELOPMENT ORGANIZATIONS GUIDE TO INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, GOVERNMENTS, PRIVATE SECTOR DEVELOPMENT AGENCIES, CIVIL SOCIETY, UNIVERSITIES, GRANTMAKERS, BANKS, MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTING FIRMS Resource Guide to Development Organizations and the Internet Introduction Welcome to the directory of development organizations 2010, Volume I: Africa The directory of development organizations, listing 63.350 development organizations, has been prepared to facilitate international cooperation and knowledge sharing in development work, both among civil society organizations, research institutions, governments and the private sector. The directory aims to promote interaction and active partnerships among key development organisations in civil society, including NGOs, trade unions, faith-based organizations, indigenous peoples movements, foundations and research centres. In creating opportunities for dialogue with governments and private sector, civil society organizations are helping to amplify the voices of the poorest people in the decisions that affect their lives, improve development effectiveness and sustainability and hold governments and policymakers publicly accountable. In particular, the directory is intended to provide a comprehensive source of reference for development practitioners, researchers, donor employees, and policymakers who are committed to good governance, sustainable development and poverty reduction, through: the financial sector and microfinance, -

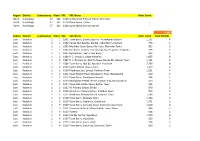

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North Koinadugu 47 162 6169 Al-Harrakan Primary School, Woredala - North Koinadugu 47 162 6179 Open Space 2,Kabo - North Koinadugu 47 162 6180 Open Space, Kamayortortor - 9,493 Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count Total PS(100) East Kailahun 1 1 1001 Town Barry, Baoma, Baoma - Kunywahun Section 1,192 4 East Kailahun 1 1 1002 Palava Hut, Baoma, Baoma - Gborgborma Section 478 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1003 Mofindor Court Barry, Mofindor, Mofindor Town 835 3 East Kailahun 1 1 1004 Methodist primary school yengema, Yengama, Yengema 629 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1005 Nyanyahun Town, Town Barry 449 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1006 R. C. School 1, Upper Masanta 1,855 6 East Kailahun 1 2 1007 R. C. Primary 11, Gbomo Town, Buedu RD, Gbomo Town 1,121 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1008 Town Barry, Ngitibu, Ngitibu 1-Kailahum 2,209 8 East Kailahun 1 2 1009 KLDEC School, new London 1,259 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1010 Methodist Sec. School, Kailahun Town 1,031 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1011 Town Market Place, Bandajuma Town, Bandajuma 640 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1012 Town Barry, Bandajuma Sinneh 294 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1013 Bandajuma Health Centre, Luawa Foiya, Bandajuma Si 473 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1014 Town Hall, Borbu-Town, Borbu- Town 315 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1015 RC Primary School, Borbu 870 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1016 Amadiyya Primary School, Kailahun Town 973 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1017 Methodist Primary School, kailahun Town 1,266 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1018 Town Barry, Sandialu Town 1,260 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1019 Town -

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Port Loko District for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN PORT LOKO DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR No. EMIS Name Of School Region District Chiefdom Address Headcount Amount Per Child Total to School North 1 240101201 A.M.E. Primary School Port Loko District Burah Magbotha 224 10000 West 2,240,000 North 2 240101205 Africa Methodist Episcopal Primary School Port Loko District Bureh Mange Bureh 255 10000 West 2,550,000 North 3 240702204 Africa Methodist Episcopal Primary School Port Loko District Maforki Mapoawn 238 10000 West 2,380,000 North 4 240101212 Africa Methodist Episcopal Primary School Port Loko District Maconteh Rosella 256 10000 West 2,560,000 North 5 240401222 African Muslim Agency Primary School Port Loko District Royema 473 10000 West 4,730,000 North 6 240803355 Agape Primary School Port Loko District Marampa Lunsar 184 10000 West 1,840,000 North 7 240901203 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Masimera 96 10000 West 960,000 North 8 240802202 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Marzmpa Lunsar 366 10000 West 3,660,000 North 9 240504205 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Koya Makabbie 87 10000 West 870,000 North 10 240501212 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Koya Malaisoko 294 10000 West 2,940,000 North Kaffu Malokoh - 11 240403206 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District 238 10000 West Bullom Lungi 2,380,000 North 12 240702207 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Maforki Old Port Loko 0 10000 West - North 13 240102224 Ahmadiyya Muslim -

Mining and HIV/AIDS Transmission Among Marampa Mining Communities in Lunsar, Sierra Leone Alphajoh Cham Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2015 Mining and HIV/AIDS Transmission Among Marampa Mining Communities in Lunsar, Sierra Leone Alphajoh Cham Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Epidemiology Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Health Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Alphajoh Cham has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Aimee Ferraro, Committee Chairperson, Public Health Faculty Dr. Hadi Danawi, Committee Member, Public Health Faculty Dr. Michael Dunn, University Reviewer, Public Health Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2015 Abstract Mining and HIV/AIDS Transmission Among Marampa Mining Communities in Lunsar, Sierra Leone by Alphajoh Cham MSc Eng, Dresden University of Technology, Germany, 2001 BSc (Hons), University of Sierra Leone, 1994 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Health Walden University October 2015 Abstract Since the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) was first reported in Sierra Leone in 1987, its prevalence rate has stabilized at 1.5% in the nation’s general population. -

Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

April 2008 NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume One February 2008 This page is intentionally left blank TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Stages in the Ward Boundary Delimitation Process 7 Stage One: Establishment of methodology including drafting of regulations 7 Stage Two: Allocation of Local Councils seats to localities 13 Stage Three: Drawing of Boundaries 15 Stage Four: Sensitization of Stakeholders and General Public 16 Stage Five: Implement Ward Boundaries 17 Conclusion 18 APPENDICES A. Database for delimiting wards for the 2008 Local Council Elections 20 B. Methodology for delimiting ward boundaries using GIS technology 21 B1. Brief Explanation of Projection Methodology 22 C. Highest remainder allocation formula for apportioning seats to localities for the Local Council Elections 23 D. List of Tables Allocation of 475 Seats to 19 Local Councils using the highest remainder method 24 25% Population Deviation Range 26 Ward Numbering format 27 Summary Information on Wards 28 E. Local Council Ward Delimitation Maps showing: 81 (i) Wards and Population i (ii) Wards, Chiefdoms and sections EASTERN REGION 1. Kailahun District Council 81 2. Kenema City Council 83 3. Kenema District Council 85 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 87 5. Kono District Council 89 NORTHERN REGION 6. Makeni City Council 91 7. Bombali District Council 93 8. Kambia District Council 95 9. Koinadugu District Council 97 10. Port Loko District Council 99 11. Tonkolili District Council 101 SOUTHERN REGION 12. Bo City Council 103 13. Bo District Council 105 14. Bonthe Municipal Council 107 15. -

Sierra Leone Understanding Land Investment Deals in Africa

Understanding Land investment deaLs in africa Country report: sierra Leone Understanding Land investment deaLs in africa Country report: sierra Leone acknowLedgements This report was researched and written by Joan Baxter under the direction of Frederic Mousseau. Anuradha Mittal and Shepard Daniel also provided substantial editorial support. We are deeply grateful to Elke Schäfter of the Sierra Leonean NGO Green Scenery, and to Theophilus Gbenda, Chair of the Sierra Leone Association of Journalists for Mining and Extractives, for their immense support, hard work, and invaluable contributions to this study. We also want to thank all those who shared their time and information with the OI researchers in Sierra Leone. Special thanks to all those throughout the country who so generously assisted the team. Some have not been named to protect their identity, but their insights and candor were vital to this study. The Oakland Institute is grateful for the valuable support of its many individual and foundation donors who make our work possible. Thank you. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication, however, are those of the Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Design: amymade graphic design, [email protected], amymade.com Editors: Frederic Mousseau & Granate Sosnoff Production: Southpaw, Southpaw.org Photograph Credits © Joan Baxter Cover photo: Cleared land by the SLA project Publisher: The Oakland Institute is a policy think tank dedicated to advancing public participation and fair debate on critical social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2011 by The Oakland Institute The text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. -

The Constitution of Sierra Leone Act, 1991

CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT SUPPLEMENT TO THE SIERRA LEONE GAZETTE EXTRAORIDARY VOL. CXXXVIII, NO. 16 dated 18th April, 2007 CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT NO. 5 OF 2007 Published 18th April, 2007 THE CONSTITUTION OF SIERRA LEONE, 1991 (Act No. 6 of 1991) PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS (DECLARATION OF CONSTITUENCIES) Short tittle ORDER, 2007 In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by Subsection (1) of section 38 of the Constitution of Sierra Leone 1991, the Electoral Commission hereby makes the following Order:- For the purpose of electing the ordinary Members of Parliament, Division of Sierra Leone Sierra Leone is hereby divided into one hundred and twelve into Constituencies. constituencies as described in the Schedule. 2 3 Name and Code Description SCHEDULE of Constituency EASTERN REGION KAILAHUN DISTRICT Kailahun This Constituency comprises of the whole of upper Bambara and District part of Luawa Chiefdom with the following sections; Gao, Giehun, Costituency DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCIES 2 Lower Kpombali and Mende Buima. Name and Code Description of Constituency (NEC The constituency boundary starts in the northwest where the Chiefdom Const. 002) boundaries of Kpeje Bongre, Luawa and Upper Bambara meet. It follows the northern section boundary of Mende Buima and Giehun, then This constituency comprises of part of Luawa Chiefdom southwestern boundary of Upper Kpombali to meet the Guinea with the following sections: Baoma, Gbela, Luawa boundary. It follows the boundary southwestwards and south to where Foguiya, Mano-Sewallu, Mofindo, and Upper Kpombali. the Dea and Upper Bambara Chiefdom boundaries meet. It continues along the southern boundary of Upper Bambara west to the Chiefdom (NEC Const. The constituency boundary starts along the Guinea/ Sierra Leone boundaries of Kpeje Bongre and Mandu. -

Climate Change Education

CLIMATE CHANGE EDUCATION May, 2014 LIBERIA FOLLOWS THE FOOTSTEPS OF SIERRA LEONE For better or for worst, Sierra Leone has stood behind it’s next door neighbour- Liberia in sharing happiness or bitter- ness. The Socio-political history of these two countries has continued to grow in such that the transplanting of one development project to the other is no more a cause for concern. The belief is that, what works well in Sierra Leone can do better in Liberia. So if Rural Finance can succeed in Sierra Leone then there is no reason for it to fail in Liberia. Pursuant to this and in reference to replicate and adapt the ap- proach and model of Sierra Leo- ne’s highly successful Rural Fi- nance and Community Improve- ment Programme, the Liberia Government through it’s Ministry of Agriculture in collaboration with the Ministry of finance and the Central Bank of Liberia saw it Rural Community Finance Programme, Liberia to copy from the approach and model of Sierra Leone’s fit to request IFAD to pilot a Ru- most successful Rural Finance and Community Improvement Programme ral Finance Programme - Rural Community Finance Programme. monitored at reasonable transac- In light of this, a delegation led by The overall goal of the Liberian tion costs. The Project is also ex- the Liberian Deputy Minister of Rural Finance Programme is to pected to provide technical assis- Agriculture, Technical Services, reduce rural poverty and house- tance to the Central Bank of Libe- Dr Subah accompanied by the hold food insecurity in Liberia on ria to develop a sound regulatory Deputy head of Microfinance and a sustainable basis through access and supervisory framework. -

Copyright © and Moral Rights for This Thesis Are Retained by the Author And/Or Other Copyright Owners

R Tarawallie, Idrissa Mamoud (2018) Public services and social cohesion at risk? : the political economy of democratic decentralisation in post‐war Sierra Leone (2004‐2014). PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/26185 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Public Services and Social Cohesion at Risk? The Political Economy of Democratic Decentralisation in Post-War Sierra Leone (2004 – 2014) Idrissa Mamoud Tarawallie Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD Department of Development Studies SOAS – University of London February 2017 1 Abstract On account of the many failures of the centralised state, decentralisation has become the preferred mode of governance in many countries in the developing world. Widely supported by international development agencies, it promises efficiency and equity in public service delivery and social cohesion in post-war societies by bringing government closer to the people. Crucial in the decentralisation promise, is resource diversion through clientelistic networks at the local level to consolidate political strongholds. -

VOLUME 3 EDITION 1 (2014) Welcome to the Journal of Sierra Leone Studies. This Is the Fi

THE JOURNAL OF SIERRA LEONE STUDIES – VOLUME 3 EDITION 1 (2014) Welcome to The Journal of Sierra Leone Studies. This is the first Journal dedicated solely to Sierra Leone to have been published for a long time. We hope that it will be of use to academics, students and anyone with an interest in what for many is a rather ‘special’ country. The Journal will not concentrate on one area of academic study and invites contributions from anyone researching and writing on Sierra Leone to send their articles to: John Birchall for consideration. Prospective contributions should normally be between 3500- 10,000 words in length, though we will in special circumstances consider longer articles and authors can select whether they wish to be peer reviewed or not. Articles should not have appeared in any other published form before. We also include a section on items of general interest – it hoped that these will inform future generations of some of the events and personalities important to the country. The Editorial Board reserves the right to suggest changes they consider are needed to the relevant author (s) and to not publish if such recommendations are ignored. We are particularly interested to encourage students working on subjects specifically relating to Sierra Leone to submit their work. Thank you so much for visiting The Journal and we hope that you (a) find it both interesting and of use to you and (b) that you will inform colleagues, friends and students of the existence of a Journal dedicated to the study of Sierra Leone. John Birchall Articles -

West Indians in West Africa

The West Indian soldier in Africa When: 1812-1927 Participants: Britain vs The Marabouts, Bamba Mihi Lahi, the Sofas, Bai Bureh Key campaigns: The Rio Pongo expedition, The Marabout War, The expeditions to Malageah, The Hut Tax War Key battles and places: Sierra Leone, The Gambia, The Gold Coast, Sabbajee, Malageah, Badibu, Rio Pongo, British Sherbro, Waima, Bagwema The West India Regiments were employed in West Africa, as the region had the same reputation as the Caribbean in that it was hotbed of disease that was fatal to Europeans; black soldiers were believed to be more resistant to the local diseases, which proved to be mostly true according to the medical reports. The West India Regiments already had a link to the area early in the nineteenth century, due to the recruiting depot that had operated in Sierra Leone 1812-1814. Many West India Regiment veterans also settled in Sierra Leone when they retired, founding towns named after people and places from British military history, including Wellington, Waterloo, Hastings and Gibraltar Town. Their presence also led to the development of a new creole language, Krio, which is still widely spoken in Sierra Leone. Their service in Africa was, in many ways, similar to their service in the Caribbean, generally consisting of garrison duties, but in Africa they saw more combat, taking part in various small expeditions and, on occasion, in larger engagements. There were countless operations over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but the following are some of the more significant events. Badibu Sabbajee Rio Pongo Malageah Waima Freetown British Sherbro Sherbro Island © The West India Committee 55 Following the British abolition of the slave trade in 1807, a large proportion of the British forces in Africa participated in actions to disrupt the trade. -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June).