Sierra Leone Smallholder Commercialization Programme Project Completion Report Main Report and Appendices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

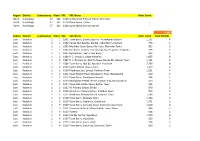

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North

Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count North Koinadugu 47 162 6169 Al-Harrakan Primary School, Woredala - North Koinadugu 47 162 6179 Open Space 2,Kabo - North Koinadugu 47 162 6180 Open Space, Kamayortortor - 9,493 Region District Constituency Ward VRC VRC Name Voter Count Total PS(100) East Kailahun 1 1 1001 Town Barry, Baoma, Baoma - Kunywahun Section 1,192 4 East Kailahun 1 1 1002 Palava Hut, Baoma, Baoma - Gborgborma Section 478 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1003 Mofindor Court Barry, Mofindor, Mofindor Town 835 3 East Kailahun 1 1 1004 Methodist primary school yengema, Yengama, Yengema 629 2 East Kailahun 1 1 1005 Nyanyahun Town, Town Barry 449 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1006 R. C. School 1, Upper Masanta 1,855 6 East Kailahun 1 2 1007 R. C. Primary 11, Gbomo Town, Buedu RD, Gbomo Town 1,121 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1008 Town Barry, Ngitibu, Ngitibu 1-Kailahum 2,209 8 East Kailahun 1 2 1009 KLDEC School, new London 1,259 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1010 Methodist Sec. School, Kailahun Town 1,031 4 East Kailahun 1 2 1011 Town Market Place, Bandajuma Town, Bandajuma 640 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1012 Town Barry, Bandajuma Sinneh 294 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1013 Bandajuma Health Centre, Luawa Foiya, Bandajuma Si 473 2 East Kailahun 1 2 1014 Town Hall, Borbu-Town, Borbu- Town 315 1 East Kailahun 1 2 1015 RC Primary School, Borbu 870 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1016 Amadiyya Primary School, Kailahun Town 973 3 East Kailahun 1 2 1017 Methodist Primary School, kailahun Town 1,266 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1018 Town Barry, Sandialu Town 1,260 4 East Kailahun 1 3 1019 Town -

Payment of Tuition Fees to Primary Schools in Port Loko District for Second Term 2019/2020 School Year

PAYMENT OF TUITION FEES TO PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN PORT LOKO DISTRICT FOR SECOND TERM 2019/2020 SCHOOL YEAR No. EMIS Name Of School Region District Chiefdom Address Headcount Amount Per Child Total to School North 1 240101201 A.M.E. Primary School Port Loko District Burah Magbotha 224 10000 West 2,240,000 North 2 240101205 Africa Methodist Episcopal Primary School Port Loko District Bureh Mange Bureh 255 10000 West 2,550,000 North 3 240702204 Africa Methodist Episcopal Primary School Port Loko District Maforki Mapoawn 238 10000 West 2,380,000 North 4 240101212 Africa Methodist Episcopal Primary School Port Loko District Maconteh Rosella 256 10000 West 2,560,000 North 5 240401222 African Muslim Agency Primary School Port Loko District Royema 473 10000 West 4,730,000 North 6 240803355 Agape Primary School Port Loko District Marampa Lunsar 184 10000 West 1,840,000 North 7 240901203 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Masimera 96 10000 West 960,000 North 8 240802202 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Marzmpa Lunsar 366 10000 West 3,660,000 North 9 240504205 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Koya Makabbie 87 10000 West 870,000 North 10 240501212 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Koya Malaisoko 294 10000 West 2,940,000 North Kaffu Malokoh - 11 240403206 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District 238 10000 West Bullom Lungi 2,380,000 North 12 240702207 Ahmadiyya Muslim Primary School Port Loko District Maforki Old Port Loko 0 10000 West - North 13 240102224 Ahmadiyya Muslim -

Mining and HIV/AIDS Transmission Among Marampa Mining Communities in Lunsar, Sierra Leone Alphajoh Cham Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2015 Mining and HIV/AIDS Transmission Among Marampa Mining Communities in Lunsar, Sierra Leone Alphajoh Cham Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Epidemiology Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Health Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Alphajoh Cham has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Aimee Ferraro, Committee Chairperson, Public Health Faculty Dr. Hadi Danawi, Committee Member, Public Health Faculty Dr. Michael Dunn, University Reviewer, Public Health Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2015 Abstract Mining and HIV/AIDS Transmission Among Marampa Mining Communities in Lunsar, Sierra Leone by Alphajoh Cham MSc Eng, Dresden University of Technology, Germany, 2001 BSc (Hons), University of Sierra Leone, 1994 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Health Walden University October 2015 Abstract Since the human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS) was first reported in Sierra Leone in 1987, its prevalence rate has stabilized at 1.5% in the nation’s general population. -

Sthjeme Fourah Bay College

M. JSi Wr- INSTITUTE ©E AF1SDCAN STHJEME FOURAH BAY COLLEGE university of sierra leone 23 JUIN 197* Africana Research ulletin FORMER FOURAH BAY COLLEGE CLINETOWN, FREETOWN. Vol. Ill No. 1 Session 1972-73 OCTOBER 1972 Editor: J. G. EDOWU HYDE Asst. Editor: J. A. S. BLAIR v.. AFRICANA RESEARCH BULLETIN CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........ James A. S. Blair 1. ARTICLES Krio Ways of 'Thought and Ev-ression ooooooooeooooooooooo» Clifford Fy1er Initiative and Response in the Sierra Leone Hinterland, 1885-1898: The Chiefs and British Intervention .. ». ... Kenneth C. Wylie and James S. Harrison 2. RESEARCH NOTE A Note on 'Country' in Political Anthropology .................. C. Magbaily Fyle 3. REVIEW W. T. Harris and Harry Sawyerr, The Springs of Mende Belief and Conduct Arthur Abraham 4. NEWS ITEM Road Development Research Project - Progress Report ................. James A. S. Blair INTRODUCTION The present issue of the Africana Research Bulletin contains as its first article a contribution from two former Visiting Research Scholars of this Institute, Professor Kenneth Wylie and Mr James Harrison» We are always glad to welcome to our pages the work of past visiting scholars and we hope that many more such contributions will be received.. This mutual co-operation between foreign scholars and this Institute is a manifestation of the approval in this country for genuine scholarly wrork to be undertaken, both by indigenous and non- national scholars. In a forthcoming issue of the Africana Research Bulletin the conditions and responsibilities of visiting research status in this Institute will be laid out clearly so that intending applicants may be familiar with the opportunities for research open to them. -

Climate Change Education

CLIMATE CHANGE EDUCATION May, 2014 LIBERIA FOLLOWS THE FOOTSTEPS OF SIERRA LEONE For better or for worst, Sierra Leone has stood behind it’s next door neighbour- Liberia in sharing happiness or bitter- ness. The Socio-political history of these two countries has continued to grow in such that the transplanting of one development project to the other is no more a cause for concern. The belief is that, what works well in Sierra Leone can do better in Liberia. So if Rural Finance can succeed in Sierra Leone then there is no reason for it to fail in Liberia. Pursuant to this and in reference to replicate and adapt the ap- proach and model of Sierra Leo- ne’s highly successful Rural Fi- nance and Community Improve- ment Programme, the Liberia Government through it’s Ministry of Agriculture in collaboration with the Ministry of finance and the Central Bank of Liberia saw it Rural Community Finance Programme, Liberia to copy from the approach and model of Sierra Leone’s fit to request IFAD to pilot a Ru- most successful Rural Finance and Community Improvement Programme ral Finance Programme - Rural Community Finance Programme. monitored at reasonable transac- In light of this, a delegation led by The overall goal of the Liberian tion costs. The Project is also ex- the Liberian Deputy Minister of Rural Finance Programme is to pected to provide technical assis- Agriculture, Technical Services, reduce rural poverty and house- tance to the Central Bank of Libe- Dr Subah accompanied by the hold food insecurity in Liberia on ria to develop a sound regulatory Deputy head of Microfinance and a sustainable basis through access and supervisory framework. -

Summary of Recovery Requirements (Us$)

National Recovery Strategy Sierra Leone 2002 - 2003 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 4. RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY 48 INFORMATION SHEET 7 MAPS 8 Agriculture and Food-Security 49 Mining 53 INTRODUCTION 9 Infrastructure 54 Monitoring and Coordination 10 Micro-Finance 57 I. RECOVERY POLICY III. DISTRICT INFORMATION 1. COMPONENTS OF RECOVERY 12 EASTERN REGION 60 Government 12 1. Kailahun 60 Civil Society 12 2. Kenema 63 Economy & Infrastructure 13 3. Kono 66 2. CROSS CUTTING ISSUES 14 NORTHERN REGION 69 HIV/AIDS and Preventive Health 14 4. Bombali 69 Youth 14 5. Kambia 72 Gender 15 6. Koinadugu 75 Environment 16 7. Port Loko 78 8. Tonkolili 81 II. PRIORITY AREAS OF SOUTHERN REGION 84 INTERVENTION 9. Bo 84 10. Bonthe 87 11. Moyamba 90 1. CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY 18 12. Pujehun 93 District Administration 18 District/Local Councils 19 WESTERN AREA 96 Sierra Leone Police 20 Courts 21 Prisons 22 IV. FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS Native Administration 23 2. REBUILDING COMMUNITIES 25 SUMMARY OF RECOVERY REQUIREMENTS Resettlement of IDPs & Refugees 26 CONSOLIDATION OF STATE AUTHORITY Reintegration of Ex-Combatants 38 REBUILDING COMMUNITIES Health 31 Water and Sanitation 34 PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS Education 36 RESTORATION OF THE ECONOMY Child Protection & Social Services 40 Shelter 43 V. ANNEXES 3. PEACE-BUILDING AND HUMAN RIGHTS 46 GLOSSARY NATIONAL RECOVERY STRATEGY - 3 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ▪ Deployment of remaining district officials, EXECUTIVE SUMMARY including representatives of line ministries to all With Sierra Leone’s destructive eleven-year conflict districts (by March). formally declared over in January 2002, the country is ▪ Elections of District Councils completed and at last beginning the task of reconstruction, elected District Councils established (by June). -

Progress Report - 2014

PROGRESS REPORT - 2014 WHO WE ARE ENGIM – Ente Nazionale Gi useppini del Murialdo (National Organization Josephites of Murialdo) - is a non profit organization established in Italy in 1977 to help young people to develop their personal, social and professional skills. Since its foundation, ENGIM is inspired by the teaching of Saint Leonardo Murialdo (1828-1900), the Founder of the Congregation of Saint Joseph. In 1987 ENGIM became also a Non Governmental Organization (extending its name as “ENGIM Internazionale” - “ENGIM International”- hereafter simply ENGIM). Supporting the missions of the St. Joseph Fathers worldwide, it starts to promote development cooperation all over the world. Today ENGIM works in 13 countries: Albania, Romania, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Colombia, Ghana, Mexico, India, Guinea Bissau, Mali and Sierra Leone. In Sierra Leone, ENGIM arrives in 1987 to help the mission of the Saint Joseph Fathers (SJFs), who already had established the “Murialdo Secondary School” and the “Vocational Training Institute” in Lunsar, Northern Province. Since then ENGIM operates in the country to accomplish the goals of SJFs and support their work. The SJFs are indeed the preferential local partner with whom ENGIM carries out its projects and activities. ENGIM not only draws support from the SJFs and its partners in the Lunsar area, but also in Freetown with the “Missionaries’ Friends Association” and the “Hope of Kent”, important partners for projects concerning the development of the fishing community of Kent. ENGIM's activities are supported and financed by private and public donors, such as the European Union, the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Italian Government, various Italian Regions and the “Conferenza Episcopale Italiana”. -

Sierra Leone

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : SIERRA LEONE Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 7 July, 2001) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 788 80 85 Fax: + 41 22 788 80 86 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 10 ACCESS TO UN HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORTS 10 HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORTS BY THE UN OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS (22 DECEMBER 2000 – 16 JUNE 2001) 10 MAIN CAUSES FOR DISPLACEMENT 10 COUNTRYWIDE DISPLACEMENT CAUSED BY MORE THAN NINE YEARS OF WIDESPREAD CONFLICT- RELATED HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES (1991- 2000) 10 MAJOR NEW DISPLACEMENT AFTER BREAK DOWN OF THE PEACE PROCESS IN MAY 2000 12 NEW DISPLACEMENT AS CONFLICT EXTENDED ACROSS THE GUINEA-SIERRA LEONE BORDER (SEPTEMBER 2000 – MAY 2001) 15 BACKGROUND OF THE CONFLICT 18 HISTORICAL OUTLINE OF THE FIRST EIGHT YEARS OF CONFLICT (1991-1998) 18 ESCALATED CONFLICT DURING FIRST HALF OF 1999 CAUSED SUBSTANTIAL DISPLACEMENT 21 CONTINUED CONFLICT DESPITE THE SIGNING OF THE LOME PEACE AGREEMENT (JULY 1999-MAY 2000) 22 PEACE PROCESS DERAILED AS SECURITY SITUATION WORSENED DRAMATICALLY IN MAY 2000 25 -

Sierraleone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report

NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION Sierra Leone Local Council Ward Boundary Delimitation Report Volume Two Meets and Bounds April 2008 Table of Contents Preface ii A. Eastern region 1. Kailahun District Council 1 2. Kenema City Council 9 3. Kenema District Council 12 4. Koidu/New Sembehun City Council 22 5. Kono District Council 26 B. Northern Region 1. Makeni City Council 34 2. Bombali District Council 37 3. Kambia District Council 45 4. Koinadugu District Council 51 5. Port Loko District Council 57 6. Tonkolili District Council 66 C. Southern Region 1. Bo City Council 72 2. Bo District Council 75 3. Bonthe Municipal Council 80 4. Bonthe District Council 82 5. Moyamba District Council 86 6. Pujehun District Council 92 D. Western Region 1. Western Area Rural District Council 97 2. Freetown City Council 105 i Preface This part of the report on Electoral Ward Boundaries Delimitation process is a detailed description of each of the 394 Local Council Wards nationwide, comprising of Chiefdoms, Sections, Streets and other prominent features defining ward boundaries. It is the aspect that deals with the legal framework for the approved wards _____________________________ Dr. Christiana A. M Thorpe Chief Electoral Commissioner and Chair ii CONSTITUTIONAL INSTRUMENT No………………………..of 2008 Published: THE LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 2004 (Act No. 1 of 2004) THE KAILAHUN DISTRICT COUNCIL (ESTABLISHMENT OF LOCALITY AND DELIMITATION OF WARDS) Order, 2008 Short title In exercise of the powers conferred upon him by subsection (2) of Section 2 of the Local Government Act, 2004, the President, acting on the recommendation of the Minister of Internal Affairs, Local Government and Rural Development, the Minister of Finance and Economic Development and the National Electoral Commission, hereby makes the following Order:‐ 1. -

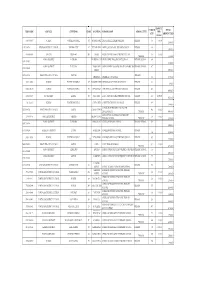

Emis Code Council Chiefdom Ward Location School Name

AMOUNT ENROLM TOTAL EMIS CODE COUNCIL CHIEFDOM WARD LOCATION SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL LEVEL PER ENT AMOUNT PAID CHILD 5103-2-09037 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 391 ROGBANGBA ABDUL JALIL ACADEMY PRIMARY PRIMARY 369 10,000 3,690,000 1291-2-00714 KENEMA DISTRICT COUNCIL KENEMA CITY 67 FULAWAHUN ABDUL JALIL ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 380 3,800,000 4114-2-06856 BO CITY TIKONKO 289 SAMIE ABDUL TAWAB HAIKAL PRIMARY SCHOOL 610 10,000 PRIMARY 6,100,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO DOWN BALLOP ABDULAI IBN ABASS PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 694 1391-2-02007 6,940,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO TAMBA ABU ABDULAI IBNU MASSOUD ANSARUL ISLAMIC MISPRIMARY SCHOOL 407 1391-2-02009 STREET 4,070,000 5208-2-10866 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL WEST III PRIMARY ABERDEEN ABERDEEN MUNICIPAL 366 3,660,000 5103-2-09002 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 397 KOSSOH TOWN ABIDING GRACE PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 62 620,000 5103-2-08963 WARDC WATERLOO RURAL 373 BENGUEMA ABNAWEE ISLAMIC PRIMARY SCHOOOL PRIMARY 405 4,050,000 4109-2-06695 BO DISTRICT KAKUA 303 KPETEMA ACEF / MOUNT HORED PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 411 10,000.00 4,110,000 Not found WARDC WATERLOO RURAL COLE TOWN ACHIEVERS PRIMARY TUTORAGE PRIMARY 388 3,880,000 ACTION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH 5205-2-09766 FREETOWN CITY COUNCIL EAST III CALABA TOWN 460 10,000 DEVELOPMENT PRIMARY 4,600,000 ADA GORVIE MEMORIAL PREPARATORY 320401214 BONTHE DISTRICT IMPERRI MORIBA TOWN 320 10,000 PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY 3,200,000 KONO DISTRICT TANKORO BONGALOW ADULLAM PRIMARY SCHOOL PRIMARY SCHOOL 323 1391-2-01954 3,230,000 1109-2-00266 KAILAHUN DISTRICT LUAWA KAILAHUN ADULLAM PRIMARY -

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone

The Chiefdoms of Sierra Leone Tristan Reed1 James A. Robinson2 July 15, 2013 1Harvard University, Department of Economics, Littauer Center, 1805 Cambridge Street, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. 2Harvard University, Department of Government, IQSS, 1737 Cambridge Street., N309, Cambridge MA 02138; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract1 In this manuscript, a companion to Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson (2013), we provide a detailed history of Paramount Chieftaincies of Sierra Leone. British colonialism transformed society in the country in 1896 by empowering a set of Paramount Chiefs as the sole authority of local government in the newly created Sierra Leone Protectorate. Only individuals from the designated \ruling families" of a chieftaincy are eligible to become Paramount Chiefs. In 2011, we conducted a survey in of \encyclopedias" (the name given in Sierra Leone to elders who preserve the oral history of the chieftaincy) and the elders in all of the ruling families of all 149 chieftaincies. Contemporary chiefs are current up to May 2011. We used the survey to re- construct the history of the chieftaincy, and each family for as far back as our informants could recall. We then used archives of the Sierra Leone National Archive at Fourah Bay College, as well as Provincial Secretary archives in Kenema, the National Archives in London and available secondary sources to cross-check the results of our survey whenever possible. We are the first to our knowledge to have constructed a comprehensive history of the chieftaincy in Sierra Leone. 1Oral history surveys were conducted by Mohammed C. Bah, Alimamy Bangura, Alieu K. -

Sierra Leone Recovery Strategy for Newly Accessible Areas

Sierra Leone Recovery Strategy for Newly Accessible Areas National Recovery Committee May 2002 Table of Contents GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................ 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................ 6 1. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ 12 1.1. The National Recovery Structure........................................................................... 12 1.2. A bottom-up approach emphasising local consultations ....................................... 12 1.3. A recovery strategy to promote stability................................................................ 13 2. RESTORATION OF CIVIL AUTHORITY................................................................. 14 2.1. District Administration .......................................................................................... 15 2.2. District Councils .................................................................................................... 16 2.3. Sierra Leone Police................................................................................................ 17 2.4. Courts..................................................................................................................... 19 2.5. Prisons.................................................................................................................... 20 2.6. Paramount Chiefs and Chiefdom