The American Revolution at Sea, 1775-1776

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Navies and the Winning of Independence

The American Navies and the Winning of Independence During the American War of Independence the navies of France and Spain challenged Great Britain on the world’s oceans. Combined, the men-o-war of the allied Bourbon monarchies outnumbered those of the British, and the allied fleets were strong enough to battle Royal Navy fleets in direct engagements, even to attempt invasions of the British isles. In contrast, the naval forces of the United States were too few, weak, and scattered to confront the Royal Navy head on. The few encounters between American and British naval forces of any scale ended in disaster for the Revolutionary cause. The Patriot attempt to hold the Delaware River after the British capture of Philadelphia in 1777, however gallant, resulted in the annihilation of the Pennsylvania Navy and the capture or burning of three Continental Navy frigates. The expedition to recapture Castine, Maine, from the British in 1779 led to the destruction of all the Continental and Massachusetts Navy ships, American privateers, and American transports involved, more than thirty vessels. And the fall of Charleston, South Carolina, to the British in 1780 brought with it the destruction or capture of four Continental Navy warships and several ships of the South Carolina Navy. Despite their comparative weakness, American naval forces made significant contributions to the overall war effort. Continental Navy vessels transported diplomats and money safely between Europe and America, convoyed shipments of munitions, engaged the Royal Navy in single ship actions, launched raids against British settlements in the Bahamas, aggravated diplomatic tensions between Great Britain and European powers, and carried the war into British home waters and even onto the shores of England and Scotland. -

Richatd Henry Lee 0Az-1Ts4l Although He Is Not Considered the Father of Our Country, Richard Henry Lee in Many Respects Was a Chief Architect of It

rl Name Class Date , BTocRAPHY Acrtvrry 2 Richatd Henry Lee 0az-1ts4l Although he is not considered the father of our country, Richard Henry Lee in many respects was a chief architect of it. As a member of the Continental Congress, Lee introduced a resolution stating that "These United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States." Lee's resolution led the Congress to commission the Declaration of Independence and forever shaped U.S. history. Lee was born to a wealthy family in Virginia and educated at one of the finest schools in England. Following his return to America, Lee served as a justice of the peace for Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1757. The following year, he entered Virginia's House of Burgesses. Richard Henry Lee For much of that time, however, Lee was a quiet and almost indifferent member of political connections with Britain be Virginia's state legislature. That changed "totaIIy dissolved." The second called in 1765, when Lee joined Patrick Henry for creating ties with foreign countries. in a spirited debate opposing the Stamp The third resolution called for forming a c Act. Lee also spoke out against the confederation of American colonies. John .o c Townshend Acts and worked establish o to Adams, a deiegate from Massachusetts, o- E committees of correspondence that seconded Lee's resolution. A Declaration o U supported cooperation between American of Independence was quickly drafted. =3 colonies. 6 Loyalty to Uirginia An Active Patriot Despite his support for the o colonies' F When tensions with Britain increased, separation from Britain, Lee cautioned ! o the colonies organized the Continental against a strong national government. -

The Navy Turns 245

The Navy Turns 245 "A good Navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guaranty of peace." - Theodore Roosevelt "I can imagine no more rewarding a career. And any man who may be asked in this century what he did to make his life worthwhile, I think can respond with a good deal of pride and satisfaction: 'I served in the United States Navy.'" - John F. Kennedy October 13 marks the birthday of the U.S. Navy, which traces its roots back to the early days of the American Revolution. On October 13, 1775, the Continental Congress established a naval force, hoping that a small fleet of privateers could attack British commerce and offset British sea power. The early Continental navy was designed to work with privateers to wage tactical raids against the transports that supplied British forces in North America. To accomplish this mission the Continental Congress purchased, converted, and constructed a fleet of small ships -- frigates, brigs, sloops, and schooners. These navy ships sailed independently or in pairs, hunting British commerce ships and transports. Two years after the end of the war, the money-poor Congress sold off the last ship of the Continental navy, the frigate Alliance. But with the expansion of trade and shipping in the 1790s, the possibility of attacks of European powers and pirates increased, and in March 1794 Congress responded by calling for the construction of a half-dozen frigates, The United States Navy was here to stay With thousands of ships and aircraft serving worldwide, the U.S. Navy is a force to be reckoned with. -

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia

Battle of Valcour Island - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Valcour_Island Coordinates: 44°36′37.84″N 73°25′49.39″W From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The naval Battle of Valcour Island, also known as the Battle of Valcour Bay, took place on October 11, 1776, on Battle of Valcour Island Lake Champlain. The main action took place in Valcour Part of the American Revolutionary War Bay, a narrow strait between the New York mainland and Valcour Island. The battle is generally regarded as one of the first naval battles of the American Revolutionary War, and one of the first fought by the United States Navy. Most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed by a British force under the overall direction of General Guy Carleton. However, the American defense of Lake Champlain stalled British plans to reach the upper Hudson River valley. The Continental Army had retreated from Quebec to Fort Royal Savage is shown run aground and burning, Ticonderoga and Fort Crown Point in June 1776 after while British ships fire on her (watercolor by British forces were massively reinforced. They spent the unknown artist, ca. 1925) summer of 1776 fortifying those forts, and building additional ships to augment the small American fleet Date October 11, 1776 already on the lake. General Carleton had a 9,000 man Location near Valcour Bay, Lake Champlain, army at Fort Saint-Jean, but needed to build a fleet to carry Town of Peru / Town of Plattsburgh, it on the lake. -

030321 VLP Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga readies for new season LEE MANCHESTER, Lake Placid News TICONDEROGA — As countered a band of Mohawk Iro- name brought the eastern foothills American forces prepared this quois warriors, setting off the first of the Adirondack Mountains into week for a new war against Iraq, battle associated with the Euro- the territory worked by the voya- historians and educators in Ti- pean exploration and settlement geurs, the backwoods fur traders conderoga prepared for yet an- of the North Country. whose pelts enriched New other visitors’ season at the site of Champlain’s journey down France. Ticonderoga was the America’s first Revolutionary the lake which came to bear his southernmost outpost of the War victory: Fort Ticonderoga. A little over an hour’s drive from Lake Placid, Ticonderoga is situated — town, village and fort — in the far southeastern corner of Essex County, just a short stone’s throw across Lake Cham- plain from the Green Mountains of Vermont. Fort Ticonderoga is an abso- lute North Country “must see” — but to appreciate this historical gem, one must know its history. Two centuries of battle It was the two-mile “carry” up the La Chute River from Lake Champlain through Ticonderoga village to Lake George that gave the site its name, a Mohican word that means “land between the wa- ters.” Overlooking the water highway connecting the two lakes as well as the St. Lawrence and Hudson rivers, Ticonderoga’s strategic importance made it the frontier for centuries between competing cultures: first between the northern Abenaki and south- ern Mohawk natives, then be- tween French and English colo- nizers, and finally between royal- ists and patriots in the American Revolution. -

The Articles of Confederation Creating A

THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION During the American Revolution, Americans drafted the Articles of Confederation to set up a new government independent of Britain. The Articles served as the constitution of the United States until 1789, when a new constitution was adopted. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, tension grew between the colonists and Britain. In 1765, 27 delegates from nine colonies met to oppose legislation passed by Parliament imposing a stamp tax on trade items. The delegates to the Stamp Act Congress drew up a statement of rights and grievances and agreed to stop importing goods from Britain. Parliament repealed the Stamp Tax Act. But it continued to impose new taxes on the colonies, and hostility to Britain kept growing. In 1773, some colonists protested a tax on tea by dressing up as Indians, boarding three British ships, and dumping their cargo of tea into the harbor. In response to the Boston Tea Party, Britain closed the Port of Boston. In turn, colonists convened the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September 1774. There was significant disagreement among the delegates. Many had supported efforts to repeal the offensive laws, but had no desire for independence. Even after battles broke out at Lexington and Concord in 1775 and the colonies began assembling troops to fight the British, many delegates remained loyal to the king. John Hewes, a delegate from North Carolina wrote in July 1775: “We do not want to be independent; we want no revolution . we are loyal subjects to our present most gracious Sovereign.” Many delegates felt a strong sense of loyalty to the Empire. -

Chronology of the American Revolution

INTRODUCTION One of the missions of The Friends of Valley Forge Park is the promotion of our historical heritage so that the spirit of what took place over two hundred years ago continues to inspire both current and future generations of all people. It is with great pleasure and satisfaction that we are able to offer to the public this chronology of events of The American Revolution. While a simple listing of facts, it is the hope that it will instill in some the desire to dig a little deeper into the fascinating stories underlying the events presented. The following pages were compiled over a three year period with text taken from many sources, including the internet, reference books, tapes and many other available resources. A bibliography of source material is listed at the end of the book. This publication is the result of the dedication, time and effort of Mr. Frank Resavy, a long time volunteer at Valley Forge National Historical Park and a member of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. As with most efforts of this magnitude, a little help from friends is invaluable. Frank and The Friends are enormously grateful for the generous support that he received from the staff and volunteers at Valley Forge National Park as well as the education committee of The Friends of Valley Forge Park. Don R Naimoli Chairman The Friends of Valley Forge Park ************** The Friends of Valley Forge Park, through and with its members, seeks to: Preserve…the past Conserve…for the future Enjoy…today Please join with us and help share in the stewardship of Valley Forge National Park. -

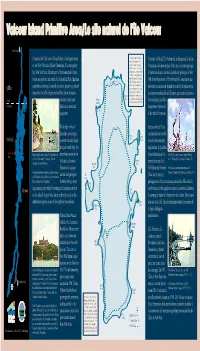

Valcour Primitive Area

Chambly Canal L’île Valcour comporte 12 km de Comprised of 1,100 acres, Valcour Island is the largest island sentiers de randonnée et 25 Couvrant 4,45 km2, l’île Valcour est la plus grande île du lac emplacements de camping on the New York side of Lake Champlain. It is managed by désignés. Des permis de camping Champlain, côté new-yorkais. Cette zone de nature protégée gratuits d’une durée maximale de the New York State Department of Environmental Conser- 14 jours sont émis par un gardien à l’intérieur du parc des Adirondacks est gérée par le New du parc. Par ailleurs, le site ayant vation as a primitive area within the Adirondack Park. Emphasis adopté le principe du premier York State Department of Environmental Conservation qui is placed on restoring its natural condition, preserving cultural arrivé, premier servi, aucune réser- préconise la restauration du milieu naturel et la préservation Quebec vation n’est acceptée. Pour de plus resources, and affording recreation that does not require amples renseignements sur l’île des ressources culturelles de l’île ainsi que les activités récréa- Beauty Valcour, veuillez communiquer Bay avec le Department of Environmen- Canada extensive man-made Valcour tives n’exigeant pas d’am- Landing tal Conservation au (518) 897-1200. United States facilities or motorized énagements importants equipment. ni de matériel motorisé. With eight miles of Avec sa côte de 13 km shoreline, consisting of constituée d’une variété Spoon Spoon New York a variety of rocky ledges Bay Island de corniches rocheuses and quiet sandy bays, the surplombant de paisibles You Are Here Boating along the rocky ledges of Valcour Island at the recreational potential on baies sablonneuses, le “Baby Blues,” similar to scenes found on Valcour Peru turn of the 19th century. -

American Self-Government: the First & Second Continental Congress

American Self-Government: The First and Second Continental Congress “…the eyes of the virtuous all over the earth are turned with anxiety on us, as the only depositories of the sacred fire of liberty, and…our falling into anarchy would decide forever the destinies of mankind, and seal the political heresy that man is incapable of self-government.” ~ Thomas Jefferson Overview Students will explore the movement of the colonies towards self-government by examining the choices made by the Second Continental Congress, noting how American delegates were influenced by philosophers such as John Locke. Students will participate in an activity in which they assume the role of a Congressional member in the year 1775 and devise a plan for America after the onset of war. This lesson can optionally end with a Socratic Seminar or translation activity on the Declaration of Independence. Grades Middle & High School Materials • “American Self Government – First & Second Continental Congress Power Point,” available in Carolina K- 12’s Database of K-12 Resources (in PDF format): https://k12database.unc.edu/wp- content/uploads/sites/31/2021/01/AmericanSelfGovtContCongressPPT.pdf o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode” o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to [email protected] • The Bostonians Paying the Excise Man, image attached or available in power point • The Battle of Lexington, image attached or available in power -

From Themselves, the Story Is Very Dark. General Howe Is Arrived Safe at Hallifax,7 Some Say, Having Been Repulsed at New York

216 To MANN 5 JUNE 1776 from themselves, the story is very dark. General Howe is arrived safe at Hallifax,7 some say, having been repulsed at New York. The American Admiral Hopkins,8 with three or four ships9 has been worsted and disgraced by a single frigate.10 Your Bible the Gazette will tell you more particulars,11 I suppose, for I have not yet seen it; and the Alamains of the Court have given Howe12 a victory, and Hopkins chains, which I do not believe will appear in that chronicle; however, you may certainly sing some Te Deums in your own chapel. These triumphs have come on the back of a very singular revolu tion13 which has happened in the penetralia, and made very great 7. 'Another account says, that General transmitted from Halifax, 25 April, was Howe is arrived at Halifax, after having published in the London Gazette No. attempted to land at New York, but was 11672, 4-8 June, sub 8 June (see also prevented by the provincials there, who Shuldham's dispatch of 19 April with were said to be 30,000 strong' (London enclosures, in Dispatches of Molyneux Chronicle, loc cit.). Howe sailed from Shuldham Vice-Admiral of the Blue, ed. Boston 27 March (ante 17 May 1776, n. 1) Neeser, New York, 1913, pp. 177-83). directly for Halifax, and dropped anchor 9. The 'rebel armed vessels' are listed in Halifax harbour 'Wednesday, April (ibid.), as the frigates Alfred, commanded 3d ... at 7 in the evening' ('Journals by Hopkins and Columbus, the brigs of Lieut.-Col. -

Social-Ecological Resilience on New Providence (The Bahamas)

Social-Ecological Resilience on New Providence (Th e Bahamas) A Field Trip Report – Summary Arnd Holdschlag, Jule Biernatzki, Janina Bornemann, Lisa-Michéle Bott, Sönke Denker, Sönke Diesener, Steffi Ehlert, Anne-Christin Hake, Philipp Jantz, Jonas Klatt, Christin Meyer, Tobias Reisch, Simon Rhodes, Julika Tribukait and Beate M.W. Ratter Institute of Geography ● University of Hamburg ● Germany Hamburg 2012 Social-Ecological Resilience on New Providence (The Bahamas) Introduction In the context of increasing natural or man-made governments and corporations. Recent island hazards and global environmental change, the studies have suggested limits in the interdiscipli- study of (scientific and technological) uncertain- nary understanding of long-term social and eco- ty, vulnerability and resilience of social-ecolo- logical trends and vulnerabilities. Shortcomings gical systems represents a core area of human-en- are also noted when it comes to the integration of vironmental geography (cf. CASTREE et al. 2009; local and traditional knowledge in assessing the ZIMMERER 2010). Extreme geophysical events, impacts of external stressors (e.g. MÉHEUX et al. coupled with the social construction and pro- 2007; KELMAN/WEST 2009). duction of risks and vulnerabilities (viewed as ha- In the Caribbean, small island coastal ecosy- zards), raise questions on the limits of knowledge stems provide both direct and indirect use values. and create long-term social uncertainty that has Indirect environmental services of coral reefs, sea to be acknowledged as such. Recent means of so- grass beds and coastal mangroves include the cioeconomic production and consumption have protection of coastlines against wave action and frequently led to the loss or degradation of ecosy- erosion, as well as the preservation of habitats stem services on which humans depend (HASSAN of animals including those of commercial impor- et al. -

Challenges of Aerodrome Pavement Maintenance in an Island Nation

By The Bahamas Department of Civil Aviation Aerodrome Inspectors: Mr. Marcus A. Evans esq. and Ms. Charlestina Knowles . Understand The Bahamas . Aviation In The Bahamas . Aerodromes in The Bahamas . Importance of Aviation in The Bahamas . Challenges of Pavement Maintenance . The Treasure In Treasure Cay . The Commonwealth of the Bahamas is an island nation located in the Atlantic Ocean. It has 700 islands and cays in the Atlantic Ocean stretching over 13,940 km². Approximately only 40 of the 700 islands are inhabited. The 2 majors cities in The Bahamas are: Nassau, which is in New Providence and the capital city and Freeport, which is in Grand Bahama. On July 10th 1973 The Bahamas gained Independence from Great Britain. The Bahamas has an approximate population 380,000 people. 65% of the population live on the island of New Providence (Nassau). The remaining Bahamian islands are referred to as the “Family Islands”. The Bahamas is located in the Hurricane belt. Our tropical cyclone season extends from June 1st to November 30th. The weather is subtropical climate. A total of 56 Aerodromes in The Bahamas . 28 Government operated . 28 Privately operated . Principle Aerodromes –Typical Aircraft: Code C • Lynden Pindling International (Nassau, Bahamas) • Grand Bahama International (Freeport, Bahamas) . Family Island Aerodromes –Typical Aircraft: Dash-8 • Busiest Family Island aerodrome is Marsh Harbor International (Abaco, Bahamas) . Tourism relations account for 60% of the country’s GDP. Over 65% of our visitors arrive by air. Medical emergencies on the Family Islands typically require air transport to New Providence, Freeport and neighbouring nations. Air Transport is the most efficient means of transport for medical emergencies throughout Family Island.