Backchannels in Spoken Turkish a Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TANZIMAT in the PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) and LOCAL COUNCILS in the OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840S to 1860S)

TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s) Dissertation zur Erlangung der Würde einer Doktorin der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel von ANNA VAKALIS aus Thessaloniki, Griechenland Basel, 2019 Buchbinderei Bommer GmbH, Basel Originaldokument gespeichert auf dem Dokumentenserver der Universität Basel edoc.unibas.ch ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Historischen Fakultät der Universität Basel, auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Maurus Reinkowski und Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yonca Köksal (Koç University, Istanbul). Basel, den 05/05/2017 Der Dekan Prof. Dr. Thomas Grob 2 ANNA VAKALIS, ‘TANZIMAT IN THE PROVINCE: NATIONALIST SEDITION (FESAT), BANDITRY (EŞKİYA) AND LOCAL COUNCILS IN THE OTTOMAN SOUTHERN BALKANS (1840s TO 1860s)’ TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………..…….…….….7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………………………………………...………..………8-9 NOTES ON PLACES……………………………………………………….……..….10 INTRODUCTION -Rethinking the Tanzimat........................................................................................................11-19 -Ottoman Province(s) in the Balkans………………………………..…….………...19-25 -Agency in Ottoman Society................…..............................................................................25-35 CHAPTER 1: THE STATE SETTING THE STAGE: Local Councils -

Letters from Vidin: a Study of Ottoman Governmentality and Politics of Local Administration, 1864-1877

LETTERS FROM VIDIN: A STUDY OF OTTOMAN GOVERNMENTALITY AND POLITICS OF LOCAL ADMINISTRATION, 1864-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Mehmet Safa Saracoglu ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Carter Vaughn Findley, Adviser Professor Jane Hathaway ______________________ Professor Kenneth Andrien Adviser History Graduate Program Copyright by Mehmet Safa Saracoglu 2007 ABSTRACT This dissertation focuses on the local administrative practices in Vidin County during 1860s and 1870s. Vidin County, as defined by the Ottoman Provincial Regulation of 1864, is the area that includes the districts of Vidin (the administrative center), ‛Adliye (modern-day Kula), Belgradcık (Belogradchik), Berkofça (Bergovitsa), İvraca (Vratsa), Rahova (Rahovo), and Lom (Lom), all of which are located in modern-day Bulgaria. My focus is mostly on the post-1864 period primarily due to the document utilized for this dissertation: the copy registers of the county administrative council in Vidin. Doing a close reading of these copy registers together with other primary and secondary sources this dissertation analyzes the politics of local administration in Vidin as a case study to understand the Ottoman governmentality in the second half of the nineteenth century. The main thesis of this study contends that the local inhabitants of Vidin effectively used the institutional framework of local administration ii in this period of transformation in order to devise strategies that served their interests. This work distances itself from an understanding of the nineteenth-century local politics as polarized between a dominating local government trying to impose unprecedented reforms designed at the imperial center on the one hand, and an oppressed but nevertheless resistant people, rebelling against the insensitive policies of the state on the other. -

The Poetry of Nazim Hikmet

THE BELOVED UNVEILED: CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN MODERN TURKISH LOVE POETRY (1923-1980) LAURENT JEAN NICOLAS MIGNON SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD ProQuest Number: 10731706 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731706 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 Abstract The thesis explores the ideological aspect of modern Turkish love poetry by focusing on the works of major poets and movements between 1923 and 1980. The approach to the theme of love was metaphorical and mystical in classical Ottoman poetry. During the period of modernisation (1839-1923), poets either rejected the theme of love altogether or abandoned Islamic aesthetics and adopted a Parnassian approach arguing that love was the expression of desire for physical beauty. A great variety of discourses on love developed during the republican period. Yahya Kemal sets the theme of love in Ottoman Istanbul and mourns the end of the relationship with the beloved who incarnates his conservative vision of national identity. -

Serbia's Sandzak: Still Forgotten

SERBIA'S SANDZAK: STILL FORGOTTEN Europe Report N°162 – 8 April 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. SANDZAK'S TWO FACES: PAZAR AND RASCIA ................................................ 2 A. SEEKING SANDZAK ...............................................................................................................2 B. OTTOMAN SANDZAK.............................................................................................................3 C. MEDIEVAL RASCIA ...............................................................................................................4 D. SERBIAN SANDZAK ...............................................................................................................4 E. TITOISM ................................................................................................................................5 III. THE MILOSEVIC ERA ................................................................................................ 7 A. WHAT'S IN A NAME? .............................................................................................................7 B. COLLIDING NATIONALISMS...................................................................................................8 C. STATE TERROR ...................................................................................................................10 -

The 2015 CSO Sustainability Index for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia

The 2015 CSO Sustainability Index for Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia Developed by: United States Agency for International Development Bureau for Europe and Eurasia Technical Support Office (TSO), Democracy and Governance (DG) Division TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................................. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................ 1 2015 CSO SUSTAINABILITY INDEX SCORES ......................................................................................................... 11 ALBANIA ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 12 ARMENIA ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 21 AZERBAIJAN ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 32 BELARUS ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Hurrem Sultan, Safiye Sultan, Kösem Sultan)

T. C. ULUDAĞ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TÜRK DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI YENİ TÜRK EDEBİYATI BİLİM DALI TARİHÎ ROMANLARIMIZDA ÜÇ HASEKİ SULTAN (HURREM SULTAN, SAFİYE SULTAN, KÖSEM SULTAN) (YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ) Sibel ARKAN Danışman Yard. Doç. Dr. Mustafa ÜSTÜNOVA BURSA 2006 1 T. C. ULUDAĞ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ MÜDÜRLÜĞÜNE ........................................................................................................ Anabilim/Anasanat Dalı, ............................................................................ Bilim Dalı’nda ...............................numaralı …………………….................. ..........................................’nın hazırladığı “.......................................... ...................................................................................................................................................” konulu ................................................. (Yüksek Lisans/Doktora/Sanatta Yeterlik Tezi/Çalışması) ile ilgili tez savunma sınavı, ...../...../ 20.... günü ……… - ………..saatleri arasında yapılmış, sorulan sorulara alınan cevaplar sonunda adayın tezinin/çalışmasının ……………………………..(başarılı/başarısız) olduğuna …………………………(oybirliği/oy çokluğu) ile karar verilmiştir. Sınav Komisyonu Başkanı Akademik Unvanı, Adı Soyadı Üniversitesi Üye (Tez Danışmanı) Üye Akademik Unvanı, Adı Soyadı Akademik Unvanı, Adı Soyadı Üniversitesi Üniversitesi Üye Üye Akademik Unvanı, Adı Soyadı Akademik Unvanı, Adı Soyadı Üniversitesi Üniversitesi Ana Bilim Dalı Başkanı Akademik -

Review Compassionate Care: Can It Be Defined, Provided, and Measured?

JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRIC NURSING DOI: 10.14744/phd.2019.20082 J Psychiatric Nurs 2020;11(1):64-69 Review Compassionate care: Can it be defined, provided, and measured? 1 2 Tuğba Pehlivan, Perihan Güner 1Koç University Hospital, Educator Nurse, İstanbul, Turkey 2Department of Psychiatric Nursing, Koç University Faculty of Nursing, İstanbul, Turkey Abstract The concept of compassion inherent in the nursing profession is a significant value. It motivates nurses to act ethically and in a sensitive way while providing care. Compassion is an essential element of good nursing care. Thus, com- passionate care is not only a significant part of modern patient care but also a vital function of professional nursing. Although it is known as a fundamental characteristic of nursing, there are limited data about the characteristics of com- passion. More data is needed regarding whether and how often compassion is included in nursing practices. As with the concept of compassion, there are difficulties with the exact definition of compassionate care, what compassionate care behaviors include, and how provision of compassionate care can be proven or measured. This review compre- hensively discusses information regarding the concept of compassion and its significance in nursing, compassionate care, and compassionate care behaviors. We also discuss measurement of compassionate care in accordance with the current literature. Keywords: Compassion; compassionate care; Compassionate care behaviors; measurement tools; nursing care. as awareness of the pain of others and the desire to relieve their What is known on this subject? [1,2] • Compassion and compassionate care are the most fundamental and pain. Compassion requires personally understanding the essential concepts for the nursing profession and therefore for patient others’ pain. -

World-Ranking-F-57Kg-April-2017

WTF Official Ranking Report World Ranking F-57kg April 2017 (Includes Events until end of March) World Rank Member Name Member Number Country Total Points 1 Jade JONES GBR-1502 Great Britain 614.86 2 Eva CALVO GOMEZ ESP-1528 Spain 399.93 3 Hedaya MALAK EGY-1629 Egypt 327.35 4 Nikita GLASNOVIC SWE-1512 Sweden 287.53 5 Mayu HAMADA JPN-1503 Japan 256.02 6 Ah-reum LEE KOR-2078 Republic of Korea 203.94 7 Raheleh ASEMANI BEL-1614 Belgium 151.72 8 Kimia ALIZADEH ZENOORIN IRI-5601 Iran 149.94 9 Martina ZUBCIC CRO-1502 Croatia 143.49 10 Anna-lena FROEMMING GER-1535 Germany 140.73 11 Skylar PARK CAN-1793 Canada 138.69 12 Paulina ARMERIA MEX-1848 Mexico 127.65 13 Evelyn GONDA CAN-1535 Canada 119.76 14 Carolena CARSTENS PAN-1503 Panama 105.37 15 Hatice Kubra ILGUN TUR-1551 Turkey 101.87 16 Durdane ALTUNEL TUR-1566 Turkey 101.75 17 Edina KOTSIS HUN-1502 Hungary 92.15 18 Patrycja ADAMKIEWICZ POL-1531 Poland 90.38 19 So-hee KIM KOR-1599 Republic of Korea 82.14 20 Doris PATIÑ O COL-1502 Colombia 75.53 21 Joana CUNHA POR-1514 Portugal 72.46 22 Cheyenne LEWIS USA-1548 United States of America 72.36 23 Ana ZANINOVIC CRO-1510 Croatia 72.29 24 Josiane LIMA BRA-1505 Brazil 71.79 25 Phannapa HARNSUJIN THA-1532 Thailand 71.44 26 Rafaela ARAUJO BRA-1508 Brazil 69.91 27 Daria MININA RUS-1573 Russia 69.43 28 Aleksandra RADMILOVIC SRB-1508 Serbia 68.32 29 Bineta DIEDHIOU SEN-1519 Senegal 65.87 30 Ara WHITE USA-2624 United States of America 62.66 31 Lijun ZHOU CHN-2187 China 62.12 32 Rangsiya NISAISOM THA-1506 Thailand 56.92 33 Bruna VULETIC CRO-1818 Croatia 54.79 -

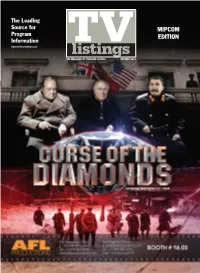

Mipcom Edition

*LIST_1013_COVER_LIS_410_COVER 9/19/13 6:13 PM Page 2 The Leading Source for MIPCOM Program EDITION Information www.worldscreenings.com THE MAGAZINE OF PROGRAM LISTINGS OCTOBER 2013 MIP_APP_2013_Layout 1 9/19/13 7:35 PM Page 1 World Screen App For iPhone and iPad DOWNLOAD IT NOW Program Listings | Stand Numbers | Event Schedule | Daily News Photo Blog | Hotel and Restaurant Directories | and more... Sponsored by Brought to you by *LIST_1013_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/19/13 6:03 PM Page 598 TV LISTINGS 3 In This Issue 4K MEDIA 53 West 23rd St., 11/Fl. 3 22 New York, NY 10010, U.S.A. 4K Media HBO 9 Story Entertainment Hoho Rights Tel: (1-212) 590-2100 Imagina International Sales 4 IMPS e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] 41 Entertainment Incendo A+E Networks website: www.yugioh.com ABC Commercial 23 ABS-CBN Corporation ITV-Inter Medya ITV Studios Global Entertainment 6 Kanal D activeTV Keshet International AFL Productions Ledafilms Alfred Haber Distribution all3media international 24 Stand: 13.11 American Cinema International Lionsgate Entertainment Contact: Shinichi Hanamoto, chmn. & pres. Mance Media 9 Story’s Peg + Cat 7 MarVista Entertainment corp. officer; Kristen Gray, SVP, business affairs; American Greetings Properties MediaBiz Animasia Studio Jennifer Coleman, VP, lic. & mktg.; Kaz Haruna; Peg + Cat (2-5 animated, 80x11 min.) Fol- APT Worldwide 25 Brian Lacey, intl. broadcast dist. cnslt. lows an adorable spirited little girl, Peg, and Armoza Formats MediaCorp Mediatoon Distribution her sidekick, Cat, as they embark on adven- 8 Miramax tures while learning basic math concepts Artear Mission Pictures International Artist View Entertainment Mondo TV S.p.A. -

Türk Televizyon Dizilerinde Yaşanan Roman Uyarlamasi Sorunlari (Kahperengi Romani-Merhamet Dizisi Örneği)

İNÖNÜ ÜNİVERSİTESİ KÜLTÜR VE SANAT DERGİSİ İnönü University Journal of Culture and Art Cilt/Vol. 3 Sayı/No. 1 (2017): 19-39 TÜRK TELEVİZYON DİZİLERİNDE YAŞANAN ROMAN UYARLAMASI SORUNLARI (KAHPERENGİ ROMANI-MERHAMET DİZİSİ ÖRNEĞİ) Nural İMİK TANYILDIZI1*, Şengül KAYA 1: Fırat Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Halkla İlişkiler ve Tanıtım Bölümü, Elazığ. Özet Sinema ilk dönemlerinden itibaren, romanları kaynak olarak kullanmış ve uyarlama filmler üretmiştir. Televizyonun yaygınlaşmasıyla birlikte dizilere de konu olan romanlar, dünyanın birçok ülkesinde, birçok yapımcı için daima önemli bir kaynak olarak görülmüştür. Bu doğrultuda Türkiye’de başlangıcından beri TRT’de, sonrasında özel televizyonlarda birçok roman televizyona uyarlanmış ve bu uyarlamalar her zaman büyük bir ilgi görmüştür. Günümüzde yapılan uyarlama diziler hem televizyon, hem de edebiyat çevrelerinde büyük tartışmalara neden olmuştur. Bu tartışmaların temel nedeni ise kaynak alınan roman ile bu romanlardan üretilmiş olan uyarlama dizilerin, birçok açıdan birbirinden farklı olmasıdır. Bu konuda değişik görüşler ileri sürülmüş olsa da genel görüş, uyarlama dizilerin kaynak aldığı romandan farklı olduğu ve bu farklılığın da romana zarar verdiği yönündedir. Çalışmanın yapılmasındaki temel amaç; yazınsal bir metin olan romanların televizyona uyarlanma sürecini ve bu süreçte ortaya çıkan sorunları roman ve televizyon açısından ele alarak ortaya koymaktır. Anahtar Kelimeler: Televizyon, Roman, Uyarlama, Uyarlama Sorunları, Dizi. NOVEL ADAPTATIONS TO THE TURKISH TELEVISIONS AND ADAPTATION PROBLEMS (EXAMPLE OF KAHPERENGI NOVEL-COMPASSION SERIAL) Abstract Since its beginning, cinema has used novels as q source and has produced adapted films. With has widespread usage of television, novels have been wed as the subject of television series, and nowadays they have become an important resource for every producer throughout the world. -

Bir Hayat Bir Hikâye

BİR HAYAT BİR HİKÂYE HÜSEYİN SU BİR HAYAT, BİR HİKÂYE 1 BİR HAYAT BİR HİKÂYE Zeytinburnu Belediyesi Kültür Yayınları HÜSEYİN SU Kitap No: 57 Koordinasyon Erdem Zekeriya İskenderoğlu Nurullah Yaldız Bir Hayat Bir Hikâye Hüseyin Su Editör Aykut Ertuğrul ISBN 978-975-2485-33-4 TC Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı Sertifika No: 40688 1. Baskı İstanbul, Şubat 2019 Kitap Tasarım Salih Pulcu Tasarım Uygulama Recep Önder Baskı-Cilt Seçil Ofset Matbaacılık Yüzyıl Mh. Matbaacılar Sitesi 4. Cadde No: 77 Bağcılar İstanbul Sertifika No: 12068 444 1984 www.zeytinburnu.istanbul 2 BİR HAYAT, BİR HİKÂYE BİR HAYAT BİR HİKÂYE HÜSEYİN SU Kıymetli okurlarımız, İnsan, yeryüzüne adımını attığı ilk andan itibaren büyük bir hika- yenin içine doğar. Yaşadığı çağ, içinde bulunduğu toplum, kültürel ve sosyal atmosfer bu büyük hikayeyi belirleyen temel unsurlardır. Kendi varlığını hikayelerle anlayan, inşa eden insan, aynı büyük hikaye içinde şahsi hikayesini de inşa ederek yaşamını sürdürür. Her adım, her nefes, alınan her karar, yürünen her yol yaşayarak yazdığımız metnin cümleleri gibidir. Bütün büyük yazarlar, büyük anlatıyla sarmalanmış insanın hikayesine kulak kabartmışlar, onu görüp hissetmiş ve yazmışlardır. Elinizdeki kitap, meşgalesi hikaye olan, hikayeyi gören, yazan, ya- zarak hem kayıt altına alan hem de ona etki eden saygıdeğer yazar- larımızın hayatları ve hikayelerinin kesişimini hem ismi hem de içeriğiyle başlangıç noktası yapıyor. Ardından onların öyküleri ve öykücülüğü üzerine verimli soru ve cevaplarla derinleşip ilerliyor. Türk öyküsüne, gerek çıkardığı dergiler, gerek yaptığı yayınlar, yazdığı eserlerle şimdiden silinmez izler bırakan Hüseyin Su’nun titizlikle belirlediği 14 öykücüyle icra ettiği “Bir Hayat Bir Hikaye” konuşmaları, hem edebiyat tarihi açısından hem öykücülüğümüz açısından dikkatli gözler tarafından hep el üstünde tutulacaktır diye umuyorum. -

Hayvanlara Şefkat Ve Merhamet Açısından Bazı Cahiliye Âdetlerine Son Verilmesi

Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi Yıl: 2014/2, Sayı: 33 Review of the Faculty of Divinity, University of Süleyman Demirel Year:2014/2, Number:33 HAYVANLARA ŞEFKAT VE MERHAMET AÇISINDAN BAZI CAHİLİYE ÂDETLERİNE SON VERİLMESİ Murat SARICIK∗ Öz Allah Rahman ve Rahimdir. Hz. Peygamber de rahmet olarak gönderilmiştir. Bu açıdan İslam’da hayvanlara ve insanlara merhamet asıldır. Hayvan haklarına, onlara eza, sıkıntı ve zarar vermemeye dikkat ve merhametli davranmak söz konusu olduğundan, İslamiyet hayvanlara merhametsizlik, eziyet ve işkence anlamına gelen uygulamaları Hz. Peygamber’ce yasaklamıştır. Hayvanlara işkence ve eziyet olan fera‘, ‘akr, mu‘âkara, ceb, şeytan yarması, nühbe, musâbara ve beliyye bunlardandır. Bu makale, sözü edilen bu gibi acımasız cahiliye âdetlerini ele alır ve irdeler. Anahtar Kelimeler: Fera‘, ‘Akr, Mu‘Âkara, Ceb, Şeytan Yarması, Nühbe, Musâbara, Beliyye, Merhamet, Eza, Şiddet. REMOVAL OF SOME CUSTOMS OF JAHILIYYAH INTERMS OF COMPASSION AND MEREY FOR ANIMALS Abstract The God is Beneficent and Merciful. Prophet Muhammed (pbuh) was also sent as a mercy. Therefore, mercy is essential for people and animals. Prophet Muhammed (pbuh) banned people from violating animal rights, mistreating against the mandtormenting to them. There are many concepts explaining to torment against animals. For instance, “fera‘”, “‘akr”, “mu‘âkara”, “ceb”, “şeytan yarması”, “nühbe”, “musâbara” and “beliyye”. This article tackles and examines brutal customs of Jahiliyya period. Key Words: fera‘, ‘akr, mu‘âkara, ceb, şeytan yarması, nühbe, musâbara, beliyye, mercy, torment, violence. ∗ Prof.Dr., Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi, İlahiyat Fakültesi, İslam Tarihi Anabilim Dalı. 61 Murat SARICIK 1. Hz. Peygamberin Tavsiyelerinden Hareketle Konuya Genel Bakış Hayvan kelimesi, Arapça “Hayevân” kelimesinden gelir. Hayevân; canlı, diri ve yaşayan demektir.