Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought Is Published Quarterly by the Dialogue Foundation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP in the HEART E.C

THE HARD REPORT' November 21, 1986 Issue # 6 (609) 654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS ERIC CLAPTON BOB GELDOF "AUGUST" "DEEP IN THE HEART E.C. DELIVERS BIG ON OF NOWHERE" HIS MOST HIGHLY ANTICIPATED ALBUM OF IN TERMS OF WRITING AND ROCKING, WE'D THE EIGHTIES! CALL THIS A WORLD CLASS SURPRISE! ATLANTIC THE KINKS KATE BUSH NINNS . "THINK VISUAL" "EXPERIMENT IV" THINK THE 12" IS A BIT THE HIGH PRIESTESS ROUGH? YOU'LL FLIP OF MIND MUSIC RATES OVER "FACTORY" AND AN "A" FOR THIS "LOST AND FOUND" CEREBRAL CONCOCTION! MCA EMI JN OE HWN PE UD SD Fs RD OA My PLUS! ETTRACKS EDDIE MONEY & TIMBUK3 CHARTSTARS * HEADLINES MOST ADDED HOWARD and the FCC 1 The Kinks "Rock & Roll Cities" (MCA) 61 2 Ann Wilson "Best Man in The World" (CAP) 53 3 Bruce Hornsby "Western Skyline..." (RCA) 40 4 Peter Gabriel "Big Time" (GEFFEN) 35 McNUTT To McWKDF HOT NUMBERS ALBUMS Billy Joel "The Bridge" 46-39 (COL) YATES Back in L.A. World Party "Private. 44-38 (CHRY.) Jason/Scorchers"Still..." 37-33 (EMI) Ben Orr "The Lace" 18-14 (E/A) DEBUTS WNEW's McEWEN Stevie Ray Vaughan "Live Alive" #23(EPIC) tubes out Robert Cray "Strong Persuader" #26 (POLY) TRACKS KBC Band "America" 92-71 JOBNAPPERS Van Halen "Rock & Roll Live" 83-63 Europe "The Final Countdown" 89-78 TEXTBOOK: Smithereens "Behind the Wall..." 57-47 GREG GILLISPIE RECORD OF THE WEEK THE STEVE MILLER BAND --FOR HIS FIRST # 1 SINCE 82's "ABRACADABRA"! INSIDE... %tea' &Mai& &Mal& EtiZiraZ CiairlZif:.-.ZaW. CfMCOLZ &L -Z Cad CcIZ Cad' Ca& &Yet Cif& Ca& Ca& Cge. -

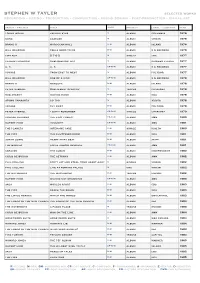

Stephen W Tayler Selected Works Recording - Mixing - Production - Composition - Sound Design - Post-Production - Visual Art

stephen w tayler selected works recording - mixing - production - composition - sound design - post-production - visual art artist - project title work project label - company year tommy bolin private eyes m album columbia 1976 gong gazeuse m album virgin 1976 brand x moroccan roll r-m album island 1976 bill bruford feels good to me r-m album e g records 1976 city boy 5 7 0 5 m single cbs 1977 claude francois quelquefois etc m album disques fleche 1977 u. k. u. k. cp-r-m album e g records 1977 voyage from east to west m album polydor 1977 bill bruford one of a kind cp-r-m album e g records 1978 brand x masques r-m album island 1978 peter gabriel 2nd album ‘scratch’ m tracks charisma 1978 rod argent moving home r-m album mca 1978 stomu yamashta go too m album arista 1978 voyage fly away r-m album polydor 1978 peter gabriel i don’t remember cp-r-m single charisma 1979 edward reekers the last forest cp-r-m album a&m 1980 rupert hine immunity cp-r-m album a&m 1981 the planets intensive care r-m single rialto 1980 the fixx the shuttered room r-m album mca 1981 jonah lewie heart skips beat r-m album stiff 1981 the models local and/or general cp-r-m album a&m 1981 caravan the album r-m album independent 1982 chris de burgh the getaway r-m album a&m 1982 phil collins don’t let her steal your heart away m single virgin 1982 phil collins live at perkins palace m vhs virgin 1982 the waterboys the waterboys r-m tracks ensign 1982 rupert hine waving not drowning cp-r-m album a&m 1983 saga worlds apart r-m album cbs 1983 the fixx reach the beach r-m album mca 1983 the little heroes watch the world r-m album emi/capitol 1983 the lords of the new church the lords of the new church r-m album irs 1983 the waterboys a pagan place m tracks ensign 1983 chris de burgh man on the line r-m album a&m 1984 honeymoon suite honeymoon suite m album wea canada 1984 howard jones human’s lib. -

To Loads of People Who Happy with This’

Bangor University Students’ Union May 2013 English Language Issue No. 232 Newspaper FREE @SerenBangor Seren.Bangor.ac.uk IRON MAN SPECIAL WHAT TO DO NEXT... INTERVIEW: LJ TAYLOR Student Summer Sessions Students’ Union organise summer activity sessions Various activities available including sports, days out and geo-caching by LJ TAYLOR tivities Development Co-ordinator at to take part in activities that may not team, making sure that everyone’s looking forward to launching this the Students’ Union. be readily accessible to them” said Mr equipment was up to scratch and that project and making the most of the new Bangor Students’ Union e project is the brainchild of the Barnard. there were no language barriers in resources that we now have available.” scheme hopes to keep Ban- Union’s activities team: AU President Strong links have been formed with the way. Quali ed coaches taught the Other planned activities include gor students active during the Emyr Bath, VP Societies and Com- the International O ce in preparation group the basics of kayaking before Geo-Caching and trips to Pu n Asummer months. munity Ash Kierans and Clubs and for the scheme which hopes to attract they toured the sheltered parts of the Island as well as a range of more Summer Sessions, which will launch Activities Development Co-ordinator International students who may be lake. traditional sports. at the end of term, will consist of a Steve Barnard. e team have worked staying in Bangor over summer and “Facilitating this activity had a fan- number of di erent activities which solidly throughout the year on in- may have less options during the qui- tastic reception, students from many will be available to any remaining stu- creasing participation and access to all eter part of the year. -

The Islamophobia Industry

Property of Pluto Press: Do Not Reproduce The Islamophobia Industry “This concise, accessible and illuminating book meets one of the most urgent needs of our time. Lean has provided a compelling counter-narrative that reveals the vested interests and highly organized networks of those who preach the virulent Islamophobia that is not only endangering world peace but is also corroding the tolerance and egalitarian ethos that should characterize Western society. This book should be required reading.” — Karen Armstrong “Islamophobia is not only about ignorance and fear. Some people purposefully nurture it and use it as a political strategy. Nathan Lean’s The Islamophobia Industry shows what is happening behind the scenes. It is an essential book for anyone who wants to understand the rationale and objectives behind those who foster this new racism against Muslims.” — Tariq Ramadan, Professor of Contemporary Islamic Studies at Oxford University and author of The Quest for Meaning “The climate of fear and cultural mistrust is one of the grim aspects of present-day society—but it doesn’t happen by accident. As this readable and well-researched book demonstrates, hatred sells; it can provide both money and power to those who profit from it. This book exposes the dirty secrets of those who try to manipulate public opinion against Muslims. It should be read by policymakers, concerned citizens, and everyone who values truth and intercultural understanding.” — Mark Juergensmeyer, Professor of Global Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. “Nathan Lean has written a book of immense importance for our times. -

Jean-Louis Schuller / Cinematographer

JEAN-LOUIS SCHULLER / CINEMATOGRAPHER DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY 2008 Bonobo / Dir. Jacques Molitor (35mm, Frakas Productions) X on Map / Dir. Jeff Desom (35mm Anamorphic, LUCIL Film Productions) FEATURE FILM DRAMA Elephants / Dir. Sally Pearce (D-21 HD Arri, NFTS Production) 2019 Hytte / Dir. Jean-Louis Schuller, Prod. aBahn, Les films Fauves Madrugada / Dir. Michael Pearce (S16mm, NFTS Production) 2013 Mammejong / Dir. Jacques Molitor (35mm, Lucil Films) 2009 House of Boys / Dir. Jean-Claude Schlimm (35mm, DELUX Productions) (Moroccan crew) 2007 Look what you have done to my heart / Dir. Michael Pearce (HD Video, NFTS Production) 2008 KIN / Dir. Brian Welsh (High Definition Video, A10 Film Productions) Launderette / Dir. Matti Harju (S16mm, NFTS Production) Ana / Dir. Theresa Von Eltz (S16mm, NFTS Production) ARTISTS’ FILM Flats / Dir. Ian Clark(S16mm, NFTS Productions) 2013 Playtime / Dir. Isaac Julien (HD, Isaac Julien Studio) 2006 Gemini / Dir. Jacques Molitor (DVcam/Pro35, IAD Production) The Remembered Film / Dir. Vicki Thornton (S16mm, Grand Duke Films) La chaire est tendre / Dir. Olivier Grinnaert (S16mm, IAD Production) 2012 Murder in Three Acts / Dir. Asli Çavusoglu (Video, Frieze Film) L’ouest est en aval / (S16mm, IAD Prod.) (camera operator) Entanglement II / Dir Ergin Çavusoglu (Video, Puma Films 4 Peace) 2011 Comma39 / Dir. Stuart Croft (S16mm, Royal College of Art) SHORT FILM DOCUMENTARY 2010 Find me loose me find me / Dir. Stuart Croft (HD, Royal College of Art) 2010 Jonsí “go live” tour (teaser) / Dir. Aneil Karia (HD, 59 Productions) 2009 The Stag Without a Heart / Dir. Stuart Croft (35mm, Royal College of Art) 2008 Yonder Stomp / Dir. Sean Clark (HDV, Goldsmith Productions) The Space Inbetween / Dir. -

Order Form Full

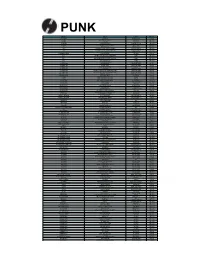

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS -

Pop Goes the Opera!! Reviews 2 the STUDENT Thursday, 8Th March 1984 News

8.3.84 20p ..___ Edinburgh University Student Newspape..---- .. Inside Art College revolt more drugs ... and pop goes the opera!! reviews 2 THE STUDENT Thursday, 8th March 1984 News . .. News ... News . .. News . .. News ... New Anti- Apartheid demonstration NEWS ,N BRIEF This Monday lunchtime comment on this action as being from the national newspapers and his home country. "provocative on behalf of the local radio stations. The EU A-AS The Conservatives' President saw a group of members Tories" have awarded themselves a major Andrew: " I wasn't here last week I Better Baths and supporters of There was great confusion as to victory for this as they have gained was in Chesterfield" Ryland, PORTOBELLO BATHS are to Edinburgh University's whether or not this mysterious a lot o f unexpected (and free) emerged briefly to defend the get a £155,000 facelift. A gym/ publicity. Through this they hope Anti-Apartheid Society Consul was going to attend his choice of speaker. Not one of the training room Is being built within luncheon appointment, with the they have achieved at least one of FCS favours apartheid, he said, the 86-year-old building, and· holding a demonstration differing factions having varied their aims for this week. they had wanted to hear Mr other Improvements will ensure outside Teviot Row stories. The Conservative group The first being to c reate an Volshenk speak and ~sk him a few better energy conservation. This Is awareness in th e public of the evils Union. They were maintained throughout that the questions. good news for the 100-odd engagement had been cancelled a of apartheid; secondly, they want Another student, Zimbabwean pensioners who, among others, sounding-off about an fortnight ago, as the event had to c lear up any misconceptions David Geddes, backed him up. -

KEY SONGS and We’Ll Tell Everyone Else

Cover-15.03.13_cover template 12/03/13 09:49 Page 1 11 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.03.13 £5.15 40 million albums sold worldwide 8 million albums sold in the UK Project1_Layout 1 12/03/2013 10:07 Page 1 Multiple Grammy Award winner to release sixth studio album ahead of his ten sold out dates in June at the O2 Arena ‘To Be Loved’ 15/04/2013 ‘It’s A Beautiful Day’ 08/04/2013 Radio Added to Heart, Radio 2, Magic, Smooth, Real, BBC Locals Highest New Entry and Highest Mover in Airplay Number 6 in Airplay Chart TV March BBC Breakfast Video Exclusive 25/03 ‘It’s A Beautiful Day’ Video In Rotation 30/03 Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway 12/04 Graham Norton Interview And Performance June 1 Hour ITV Special Expected TV Audience of 16 million, with further TVs to be announced Press Covers and features across the national press Online Over 5.5 million likes on Facebook Over 1 million followers on Twitter Over 250 million views on YouTube Live 10 Consecutive Dates At London’s O2 Arena 30th June • 1st July • 3rd July • 4th July 5thSOLD July OUT • 7thSOLD July OUT • 8thSOLD July OUT • 10thSOLD July OUT 12thSOLD July OUT • 13thSOLD July OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT Marketing Nationwide Poster Campaign Nationwide TV Advertising Campaign www.michaelbuble.com 01 MARCH15 Cover_v5_cover template 12/03/13 13:51 Page 1 11 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.03.13 £5.15 ANALYSIS PROFILE FEATURE 12 15 18 The story of physical and digital Music Week talks to the team How the US genre is entertainment retail in 2012, behind much-loved Sheffield crossing borders ahead of with new figures from ERA venue The Leadmill London’s C2C festival Pet Shop Boys leave Parlophone NEW ALBUM COMING IN JUNE G WORLDWIDE DEAL SIGNED WITH KOBALT LABEL SERVICES TALENT can say they have worked with I BY TIM INGHAM any artist for 28 years, but Parlophone have and we are very et Shop Boys have left proud of that. -

Theodore William Dwight

Appendix Beta2: The Nantes Intellectual Line Connecting brothers of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University, tracing their fraternal Big Brother/Little Brother line to the tri-Founders and their Pledges . Joseph Benson Foraker was a founder of New York Alpha, in the Class of 1869, and studied under . . .Theodore Dwight in those first years . Professor Theodore William Dwight . William Smith was brought to Penn by was influenced by Samuel Finley Benjamin Franklin . Breese Morse . . Samuel Finley Breese Morse was, . Benjamin Franklin’s endeavors were in turn, influenced by sponsored by the Frenchman Washington Allston . Jacques-Donatien Le Ray . . Washington Allston was influenced by . Jacques-Donatien Le Ray was the son Benjamin West . of René François Le Ray . . Benjamin West was influenced by . René François Le Ray was the son of William Smith . Jean Le Ray of Nantes. Below we present short biographies of the Nantes intellectual line of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity at Cornell University. “Who defends the House.” We begin with brother Joseph Benson Foraker of the Class of 1869, who studied under Professor Theodore Dwight in the University’s first years of existence. Theodore William Dwight (1822- 1892), American jurist and educator, cousin of Theodore Dwight Woolsey and of Timothy Dwight V, was born July 18, 1822 in Catskill, New York. His father was Benjamin Woolsey Dwight (1780-1850), a physician and merchant, and his grandfather was Timothy Dwight IV (1752- 1817), a prominent theologian, educator, author, and president of Yale University from 1795-1817. Theodore Dwight graduated from Hamilton College in 1840 where he studied physics under SFB Morse and John William Draper. -

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “Romancing the Stone: Invented Irish and Native American Memories in Northampton.” Author: Robert E. Weir Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 2, Summer 2018, pp. 38-71. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 38 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Summer 2018 39 Romancing the Stone: Invented Irish and Native American Memories in Northampton ROBERT E. WEIR Abstract: A six-foot stone sits atop a hillock off West Street in Northampton. Local lore holds that this is the former site of Gallows Hill and the place where two young Irishmen were hanged in 1806 for a murder they probably didn’t commit. There is a plaque upon the stone honoring the two. Not everyone is convinced, however; some think the rough monument venerates the Maminashes, a local Native American family. Other theories also exist. This article explores the truth about the monument. It is a case in historical detection and folklore but, more importantly, an examination of historical change and how historical memories are constructed and recovered. -

Warner and Sony Set for Battle

01 15FEB Cover_v3_cover template 12/02/13 17:38 Page 1 07 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.02.13 £5.15 NEWS BIG INTERVIEW ANALYSIS 05 12 27 The legendary Sir George UK bosses Jason Iley and Mike Music Week talks to pop Martin accepts his MPG Smith discuss a promising year songwriting golden boy Outstanding Contribution Award ahead for the Universal label Wayne Hector Warner and Sony set for battle PARLOPHONE BUYOUT WILL DRAMATICALLY CLOSE THE GAP BETWEEN RIVAL MAJOR LABELS ANALYSIS market headed by Universal with I BY PAUL WILLIAMS a 35.0% share and Sony second with 20.8%. arner’s £487m buyout However, had Warner W of Parlophone Label controlled the artists and Group (PLG) will put repertoire coming from PLG in it within touching distance of 2011 and 2012 it would have Sony as Universal’s biggest rival claimed around 17.5% of the in the UK. albums market, just one and a That’s according to exclusive half percentage points behind Music Week research, which Sony, while it would have been suggests the addition of around the same distance behind repertoire from the likes of Sony on singles with a market Coldplay, David Guetta and Pink share of about 19.5%. Floyd will sharply narrow the On the albums side, the most market share race for second obvious powerful addition to its place. However, Universal could ranks will be Coldplay whose end up being 80% or more ahead Mylo Xyloto was EMI’s second of both rival players. -

Architectural Analysis and Statement of Significance, Wyman Tavern, 339 Main Street, Keene, New Hampshire

ARCHITECTURAL ANALYSIS AND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE, WYMAN TAVERN, 339 MAIN STREET, KEENE, NEW HAMPSHIRE JAMES L. GARVIN CONCORD, NEW HAMPSHIRE MARCH 2013 1 ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY HISTORIC PRESERVATION JAMES L. GARVIN FARRINGTON HOUSE 30 South Main Street · Building 1, Suite 201 · Concord, New Hampshire, 03301 [email protected] http://www.james-garvin.com RESPONSE TO REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR WYMAN TAVERN Project: The Request for Proposals (RFP) issued by the Historical Society of Cheshire County on January 18, 2013, specifies that the selected consultant shall develop a Statement of Significance for the Wyman Tavern (1762) in Keene. The RFP notes that “the purpose of the Statement of Significance will be to identify character-defining architectural features of the Wyman Tavern and determine the period of significance in accordance with guidelines of the National Register of Historic Places.” The two National Register criteria under which most buildings are evaluated for integrity and significance are Criterion A , which pertains to the connection of a property with a particular event or pattern of events, and Criterion C , which deals with the design and construction of the building. Because the Request for Proposals emphasizes the character-defining architectural features of the Wyman Tavern, I propose to analyze these features for the several architectural or stylistic periods that are identifiable in the building and to develop a Criterion C analysis that places the building in an architectural context. 1 This is important because, as a rare eighteenth-century building within Cheshire County, the Wyman Tavern displays framing characteristics, and perhaps stylistic characteristics as well, that reflect norms of southern New England architecture as transmitted northerly along the Connecticut River valley.