Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NS Royal Gazette Part II

Part II Regulations under the Regulations Act Printed by the Queen’s Printer Halifax, Nova Scotia Vol. 32, No. 7 March 28, 2008 Contents Act Reg. No. Page Chartered Accountants Act Chartered Accountants By-laws–amendment ................................... 94/2008 288 Dental Act Dental Practice Review Regulations ......................................... 102/2008 346 Insurance Act Rate Decrease Filing Regulations ........................................... 101/2008 342 Motor Vehicle Act Proclamation, S. 29, S.N.S. 2007, c. 45–S. 7 and 20(a) ............................ 95/2008 292 Extension of Certificates, Licenses and Permits Regulations ....................... 93/2008 287 Municipal Government Act Polling Districts and Number of Councillors Orders for East Hants, Municipality of the District of ................................... 105/2008 351 Halifax Regional Municipality ............................................. 97/2008 294 Petroleum Products Pricing Act Prescribed Petroleum Products Prices ......................................... 99/2008 339 Prescribed Petroleum Products Prices ........................................ 106/2008 365 Public Highways Act Spring Weight Restrictions Regulations ....................................... 98/2008 324 Securities Act Proclamation of amendments to the Act, S. 65, S.N.S. 2006, c. 46–S. 1(1)(a), (b), (d), (e), (f), (i), (j), (m) and (q), S. 8, 22 to 30, 35, 36, 38, 45, 46, and 49 to 53 ...... 100/2008 341 © NS Registry of Regulations. Web version. 285 Table of Contents (cont.) Royal Gazette Part II - Regulations Vol. 32, No. 7 Summary Proceedings Act Summary Offence Tickets Regulations–amendment.............................. 96/2008 293 Youth Criminal Justice Act (Canada) Designation of Persons Who May Access Records .............................. 103/2008 349 Youth Justice Act Youth Justice Regulations–amendment....................................... 104/2008 349 In force date of regulations: As of March 4, 2005*, the date a regulation comes into force is determined by subsection 3(6) of the Regulations Act. -

Case H00508: Request to Include 5500 Inglis Street, Halifax in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 9.1.5 Heritage Advisory Committee Special Meeting June 23, 2021 TO: Chair and Members of the Heritage Advisory Committee -Original Signed- SUBMITTED BY: Kelly Denty, Executive Director of Planning and Development -Original Signed- Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: May 28, 2021 SUBJECT: Case H00508: Request to Include 5500 Inglis Street, Halifax in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality ORIGIN Application by the property owner, the Universalist Unitarian Church of Halifax. LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Heritage Property Act, R.S.N.S. 1989, c. 199. RECOMMENDATION Should 5500 Inglis Street, Halifax score 50 or more points on evaluation as a heritage property under the HRM Heritage Property Program, the Heritage Advisory Committee recommends that Regional Council: 1. Set a date for a heritage hearing to consider the inclusion of the subject property in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality; and 2. Approve the request to include 5500 Inglis Street, Halifax in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality, as shown on Map 1, as a municipal heritage property under the Heritage Property Act. Case H00508 - 5500 Inglis Street, Halifax Heritage Advisory Committee Report - 2 - June 23, 2021 BACKGROUND In March 2021, the Universalist Unitarian Church of Halifax applied to include their property at 5500 Inglis Street in the Registry of Heritage Property for the Halifax Regional Municipality. The subject property is located on the south side of Inglis Street, on the block bounded by South Bland Street to the east and Brussels Street to the west (Map 1) and contains a two-storey building that was constructed in 1823 and designed in the Georgian architectural style. -

Registered Heritage Properties

Halifax Regional Municipality - Registered Heritage Properties Beaver Bank Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 991 Windgate Drive Hallisey House 1872 Bedford Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 499 Bedford Highway Prince's Lodge Rotunda 1795 29 First Avenue Knight House 1902 15 Fort Sackville Road Fort Sackville Manor House 1800 55 Golf Links Road Golf Links Park 1922 926 Bedford Highway Moirs Mills Power House 1931 9 Spring Street The Teachery 1892 Beechville Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 1135 St. Margaret's Bay Road Beechville United Baptist Church 1844 Black Point Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 8502 Highway 3 Allen House 1852 Boutiliers Point Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 6991 Island View Drive St. James Anglican Church 1846 68 Island View Drive Boutilier House 1865 Cole Harbour Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 1436 Cole Harbour Road Cole Harbour Meeting House 1823 1445 Cole Harbour Road Kaiser-Bell House 1827 1606 Cole Harbour Road Lawlors Point Cemetery 1836 471 Poplar Drive Church/Cole Harbour Farm 1825 479 Poplar Drive Cole Harbour Farm Museum 1825 Dartmouth Construction Civic Number Street Name Property Name Date 3 Albert Street Howard Wentzell 1893 4 Albert Street William Wentzell 1876 81 Alderney Drive J. Edward Sterns 1894 17 Banook Avenue Banook Canoe Club 1913 20 Boathouse Lane Oakwood House 1902 5 Camden Street Wyndholme 1913 55 Crichton Avenue Arthur Scarfe 1910 79 Crichton Avenue Edgemere 1898 22 Dahlia Street Benjamin Russell 1873 43 Dahlia Street Fred Walker 1878 46 Dahlia Street Dr. -

NS Royal Gazette Part II

Part II Regulations under the Regulations Act Printed by the Queen's Printer Halifax, Nova Scotia Vol. 28, No. 11 May 28, 2004 Contents Act Reg. No. Page Civil Service Act Civil Service General Regulations – amendment ................................ 156/2004 244 Dairy Industry Act Bulk Haulage Regulations – amendment....................................... 154/2004 242 Health Services and Insurance Act Ambulance Fee Regulations – amendment..................................... 155/2004 243 Liquor Control Act Liquor Licensing Regulations – amendment .................................... 158/2004 248 Municipal Government Act Polling Districts Order: Halifax Regional Municipality ........................... 150/2004 194 Natural Products Act Nova Scotia Chicken Marketing Plan – amendment.............................. 157/2004 247 Summary Proceedings Act Summary Offence Tickets Regulations – amendment............................. 151/2004 224 – amendment........................................................... 152/2004 233 – amendment........................................................... 153/2004 238 NOW AVAILABLE The second issue of the 2004 subscription year of the Folio®-based Nova Scotia Regulations CD-ROM, containing the consolidated regulations of Nova Scotia and the quarterly sectional index of regulations, is now available from the Office of the Registrar of Regulations. For information or subscription please call (902) 424-6723 or visit our website at <www.gov.ns.ca/just/regulations/cd>. © NS Registry of Regulations. Web version. -

Halifax Regional Municipality Appendix a Traffic Control Manual Supplement

HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY APPENDIX A TRAFFIC CONTROL MANUAL SUPPLEMENT JANUARY 2021 HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY TRAFFIC CONTROL MANUAL SUPPLEMENT HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY TRAFFIC CONTROL MANUAL SUPPLEMENT The following provisions shall apply to all contractors/organizations and others doing work on streets under the jurisdiction of the Halifax Regional Municipality. These provisions are in addition to the “Nova Scotia Temporary Workplace Traffic Control Manual”, latest edition, (occasionally referred to in this document as the MANUAL) published by the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation & Infrastructure Renewal. For the purposes of this document, the Engineer shall be the Engineer of the Municipality; the Director of Transportation & Public Works or designate. The Traffic Authority shall be the Traffic Authority or Deputy Traffic Authority of the Municipality; as appointed by Administrative Order 12, as amended from time to time. All other definitions shall be consistent with those provided in the Nova Scotia Temporary Workplace Traffic Control Manual, latest edition (MANUAL). 1 | P a g e NEW FOR 2021 The following is a list of significant changes in this document compared to the version published in January 2020 General Changes Significant changes from previous versions highlighted in text using the year graphic in the left margin. 2021 Minor changes will not be specifically called out. The Nova Scotia Temporary Workplace Traffic Control Manual shorthand changed to “MANUAL” Part II – Additional Provisions 6 Minimum Lane -

Truck Routes By-Law T-400

BY-LAW NO. T-400 RESPECTING THE ESTABLISHMENT OF TRUCK ROUTES FOR CERTAIN TRUCKING MOTOR VEHICLES WITHIN THE HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY BE IT ENACTED by the Regional Council of the Halifax Regional Municipality, under the authority of section 194(4) of the Motor Vehicle Act, being chapter 293 of the Revised Statutes of Nova Scotia, 1989 as amended, as follows: 1. This by-law shall be known as by-law No. T-400, and may be cited as the ATruck Routes By-Law@. This by-law shall apply to those areas of the Halifax Regional Municipality located in the Urban Core Service Area. 2. In this by-law: (a) AMunicipality@ means the Halifax Regional Municipality; (b) AHighway@ means a public highway, street, lane, road, alley, park, or place including the bridges thereon and private property that is designed to be and is accessible to the general public for the operation of a motor vehicle; (c) ATruck@ in this by-law includes (i) a motor vehicle designed, used or maintained primarily for the transportation of goods, material or property, and weighing more than three thousand kilograms (3,000 kg) according to the registration certificate of the vehicle, and (ii) a tractor, roller, grader, backhoe, pay loader, road building or road maintenance equipment, or construction equipment, other than truck type vehicles, regardless of weight. (d) ATruck route@ or Aroute@ means a highway in the Municipality approved for the passage of trucks. 3. No person shall drive a truck on any highway in the Municipality except as permitted by this by-law. 4. -

Halifax Regional Municipality Traffic Control Manual Supplement

HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY APPENDIX A TRAFFIC CONTROL MANUAL SUPPLEMENT JANUARY 2012 HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY TRAFFIC CONTROL MANUAL SUPPLEMENT HALIFAX REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY TRAFFIC CONTROL MANUAL SUPPLEMENT The following provisions shall apply to all contractors/organizations and others doing work on streets within the “core area” of the Halifax Regional Municipality. These provisions are in addition to the “Temporary Workplace Traffic Control Manual”, latest revision put out by the Nova Scotia Department of Transportation & Infrastructure Renewal. 1 PERMITS With the exception of emergency situations, no work may commence on any street within the “core area” of the Halifax Regional Municipality without first obtaining a “Streets and Services” permit. This permit is required for any on-street construction/maintenance activity including temporary sidewalk and street closures, placing a crane on the street, sidewalk renewals, underground service connections, etc. Permits must be applied for well in advance (a minimum of five working days notice is required). 2 RESTRICTED HOURS OF WORK No construction or maintenance activity or equipment shall be allowed to encroach on designated roadways during peak hours except in an emergency or with the approval of the Right of Way Engineer or his designate. - Peak hour traffic shall be defined as being from 7:00 a.m. to 9:00 a.m. and from 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. from Monday to Friday, Holidays excluded and from 2:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. on the day in advance of the July 1 long weekend (if applicable) and the Natal Day and Labour Day long weekend. -

Breaking Ground

breaking ground greening the urban and1 regional landscape Conference Proceedings March 2002, Halifax breaking ground greening the urban and regional landscape 2 Breaking Ground Greening the Urban and Regional Landscape Conference Proceedings March 20-22, 2002 Pier 21 Halifax, Nova Scotia Presented by Dalhousie School of Planning, Evergreen and Ecology Action Centre Copy Editing: Frank Palermo and Dorothy Leslie Design, Production, Editing: Kasia Tota and Jennifer Meurer Contributors: Ravi Singh, Maria Jacobs, Graham Fisher, Lucy Trull, Luc Ouellet, Charlene Cressman, Heather Ternoway, Steffen Kaeubler, Jaret Lang, Pierre Heelis, Dave Stewart, Kasia Tota Cover: Collage of art work produced by conference participants Printing: etc.Press DALHOUSIE FACULTY OF PLANNING AND ARCHITECTURE has a mandate to provide high quality education, community outreach and research focused on the built and natural environment in all its aspects and scales. ECOLOGY ACTION CENTRE has a mandate to encourage a society in Nova Scotia that respects and protects nature and provides environmen- tally and economically sustainable jobs for its citizens. EVERGREEN’S mission is to bring communities and nature together for the benefit of both. We engage people in creating and sustaining healthy, dynamic, outdoor spaces in our schools, our communities and our homes. Evergreen is a registered charitable organization. Poster design: Emerald City Communications 3 CONTENTS Acknowledgements Foreword Conference Program Opening Remarks Frank Palermo Keynote Address Lucien Kroll -

EXPLORE HISTORIC HALIFAX Visit Destinationhalifax.Com for Things to Do, Day Trips and Where to Eat When You’Re in Halifax

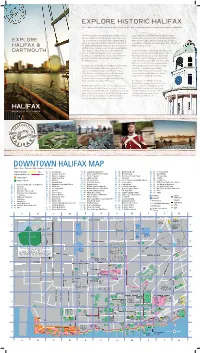

EXPLORE HISTORIC HALIFAX Visit destinationhalifax.com for things to do, day trips and where to eat when you’re in Halifax. Follow the walking route highlighted in pink and you’ll Steps lead up to the Halifax Citadel Fortifi cation which discover Halifax’s rich history and warm charm with every stands watch over the city. One of Canada’s most visited EXPLORE step. You will begin your journey at the Halifax Seaport, a National Historic Sites, this is the perfect place to discover vibrant arts and cultural district found at the south end of our military heritage and enjoy panoramic vistas of the city HALIFAX & the Halifax waterfront. Extending from Piers 19 to 23, you and the harbour beyond. will fi nd artisans, retailers, cruise terminals, event facilities, cafés, galleries, offi ces, a museum, a university and a Continue your walk west along Sackville Street and DARTMOUTH you’ll soon reach the Halifax Public Gardens. These farmers’ market. This district has been redeveloped to showcase local talent and is now a popular destination fi ne Victorian gardens are an oasis in the heart for locals and visitors alike. We invite you to discover of the city – savour a freshly brewed coffee or the Halifax Seaport. hand paddled ice cream, while enjoying a sunny afternoon, or delight in a free Sunday concert Continuing along the waterfront, you’ll fi nd shops and dining at the bandstand. Find more stylish shopping just off the boardwalk at Bishop’s Landing. Next door, and dining on Argyle Street and Spring explore our seafaring heritage at the Maritime Museum Garden Road, where some of the city’s fi nest of the Atlantic. -

2014-19 Halifax Active Transportation Priorities Plan

1 This document was prepared by staff of the Halifax Regional Municipality. Principle Authors Hanita Koblents, Active Transportation Coordinator David MacIsaac, Transportation Demand Management Program Supervisor Contributors/ Reviewers Jane Fraser, Director of Planning and Infrastructure David McCusker, P.Eng, Strategic Transportation Planning Manager Emily Macdonald, Strategic Transportation Planner Summer Student Mary McInnes, Strategic Transportation Planner Summer Student Darren Talbot, GIS Technician/Cartographer Peter Miles, GIS Technician Paul Euloth, Regional Trails Coordinator Jessie Debaie, Assistant Trails Coordinator Dawn Neil, Trails Specialist - Eastern Maria Jacobs, Regional Planner David Lane, Regional Planner Anne Sherwood, P.Eng, Design Engineer Jeff Spares, P.Eng, Senior Design Engineer Roddy MacIntyre, P.Eng, Traffic Services Supervisor Patrick Doyle, Senior Traffic Analyst Samantha Trask, Traffic Analyst Ashley Blisset, P.Eng, Development Engineer Andrew Bone, Community Planner Patricia Hughes, Supervisor, Service Design & Projects, Metro Transit Peter Bigelow, Public Lands Planning Manager Jan Skora, Coordinator, Public Lands Planning Robert Jahncke, Landscape Architect, Public Lands Planning Peter Duncan, Manager, Asset and Transportation Planning Gord Hayward, Superintendent Winter Operations Margaret Soley, Acting Coordinator - Parks Scott Penton, Active Living Coordinator Richard MacLellan, Manager, Energy & Environment Andre MacNeil, Sr. Financial Consultant, Budget & Financial Analysis This document was guided -

ACTIVE TRANSPORATION ADVISORY COMMITTEE MINUTES May 16, 2019

ACTIVE TRANSPORATION ADVISORY COMMITTEE MINUTES May 16, 2019 PRESENT: David Jackson, Chair Jillian Banfield, Vice-Chair Paul Berry Ella Dodson Jessie Harlow Kelsey Lane Sarah Manchon Elizabeth Pugh Councillor Sam Austin Councillor David Hendsbee REGRETS: Ben Buckwold Peter Fritz Emily Miller Councillor Matt Whitman STAFF: Harrison McGrath, Strategic Transportation Planner Leen Romaneh, Strategic Transportation Planning Intern Siobhan Witherbee, Active Transportation Program Planner Simon Ross-Siegel, Legislative Assistant Judith Ng’ethe, Legislative Support The following does not represent a verbatim record of the proceedings of this meeting. The agenda, reports, supporting documents, and information items circulated are online at halifax.ca. ATAC Minutes May 16, 2019 The meeting was called to order at 4:02 p.m. and adjourned at 6:04 p.m. 1. CALL TO ORDER The Chair called the meeting to order at 4:02 p.m. in Halifax Hall, City Hall, 1841 Argyle Street, Halifax. 2. APPROVAL OF MINUTES – April 18, 2019 MOVED by Councillor Hendsbee, seconded by Sarah Manchon THAT the minutes of April 18, 2019 be approved as presented. MOTION PUT AND PASSED. 3. APPROVAL OF THE ORDER OF BUSINESS AND APPROVAL OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS The Committee agreed to change the order of business to deal with items 8.1.2 and 8.1.3 prior to item 8.1.1. MOVED by Elizabeth Pugh, seconded by Ella Dodson THAT the order of business be approved as amended. Two-third majority vote required. MOTION PUT AND PASSED. 4. BUSINESS ARISING OUT OF THE MINUTES – NONE 5. CALL FOR DECLARATION OF CONFLICT OF INTERESTS – NONE 6. -

Population and Demographic Change in Downtown Halifax, 1951-2011

Who Lives Downtown? Population and demographic change in downtown Halifax, 1951-2011 William Gregory Submitted in partial completion of PLAN6000 Jill Grant (supervisor) Acknowledgements Executive Summary I would like to thank the following organizations and individuals in no particular order for their invaluable support: This study examines census information from 1951-2011 to determine how demographic indicators have changed in downtown Halifax. Population and the number of children have declined in real terms over Jill Grant for her guidance, feedback and support. the course of the study period, while the number of occupied dwellings and single households have increased considerably. A review of City The Plan Coordination and Neighbourhood Change teams at Dalhousie. of Halifax’s planning policies and land use bylaw complements the census analysis. The goal to is determine how planning practices HRM’s Centre Plan planning team for helping me to cultivate the skills I needed for this and policies have worked as incentives or deterrents to residential project. uses in Halifax’s downtown. In general, planning policies have had Phyllis Ross for her aid in obtaining census data used in this project. a quantifiable effect, although causation is difficult to determine. Urban renewal slum clearance programs in the 1950s and 1960s can Tori Prouse for providing me with essential revenue information. be directly linked to major population declines. The concentration of high density residential zones in the southern downtown correlate to Paul Spin for helping me to interpret economic data. sustained and real growth in the area. My parents for encouragement in my academic pursuits. Justine Galbraith, Abigail Franklin, and Waldo Buttons.