Manualpráctico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Political Corruption in Ukraine

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE π 7 (111) CONTENTS POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: ACTORS, MANIFESTATIONS, 2009 PROBLEMS OF COUNTERING (Analytical Report) ................................................................................................... 2 Founded and published by: SECTION 1. POLITICAL CORRUPTION AS A PHENOMENON: APPROACHES TO DEFINITION ..................................................................3 SECTION 2. POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: POTENTIAL ACTORS, AREAS, MANIFESTATIONS, TRENDS ...................................................................8 SECTION 3. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF COUNTERING UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES POLITICAL CORRUPTION ......................................................................33 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV SECTION 4. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS ......................................................... 40 ANNEX 1 FOREIGN ASSESSMENTS OF THE POLITICAL CORRUPTION Director General Anatoliy Rachok LEVEL IN UKRAINE (INTERNATIONAL CORRUPTION RATINGS) ............43 Editor-in-Chief Yevhen Shulha ANNEX 2 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SPECIFICITY, SCALE AND WAYS Layout and design Oleksandr Shaptala OF COUNTERING IN EXPERT ASSESSMENTS ......................................44 Technical & computer support Volodymyr Kekuh ANNEX 3 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SCALE AND WAYS OF COUNTERING IN PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS AND ASSESSMENTS ...................................49 This magazine is registered with the State Committee ARTICLE of Ukraine for Information Policy, POLITICAL -

For Free Distribution

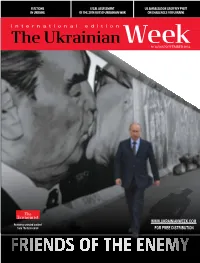

ELECTIONS LeGAL ASSESSMENT US AMBASSADOR GeOFFREY PYATT IN UKRAINE OF THE 2014 RuSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR ON CHALLENGES FOR UKRAINE № 14 (80) NOVEMBER 2014 WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION |CONTENTS BRIEFING Lobbymocracy: Ukraine does not have Rapid Response Elections: The victory adequate support in the West, either in of pro-European parties must be put political circles, or among experts. The to work toward rapid and irreversible situation with the mass media and civil reforms. Otherwise it will quickly turn society is slightly better into an equally impressive defeat 28 4 Leonidas Donskis: An imagined dialogue on several clichés and misperceptions POLITICS 30 Starting a New Life, Voting as Before: Elections in the Donbas NEIGHBOURS 8 Russia’s gangster regime – the real story Broken Democracy on the Frontline: “Unhappy, poorly dressed people, 31 mostly elderly, trudged to the polls Karen Dawisha, the author of Putin’s to cast their votes for one of the Kleptocracy, on the loyalty of the Russian richest people in Donetsk Oblast” President’s team, the role of Ukraine in his grip 10 on power, and on Russia’s money in Europe Poroshenko’s Blunders: 32 The President’s bloc is painfully The Bear, Master of itsT aiga Lair: reminiscent of previous political Russians support the Kremlin’s path towards self-isolation projects that failed bitterly and confrontation with the West, ignoring the fact that they don’t have a realistic chance of becoming another 12 pole of influence in the world 2014 -

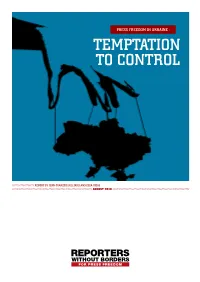

Temptation to Control

PrESS frEEDOM IN UKRAINE : TEMPTATION TO CONTROL ////////////////// REPORT BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS JULLIARD AND ELSA VIDAL ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// AUGUST 2010 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// PRESS FREEDOM: REPORT OF FACT-FINDING VISIT TO UKRAINE ///////////////////////////////////////////////////////// 2 Natalia Negrey / public action at Mykhaylivska Square in Kiev in November of 2009 Many journalists, free speech organisations and opposition parliamentarians are concerned to see the government becoming more and more remote and impenetrable. During a public meeting on 20 July between Reporters Without Borders and members of the Ukrainian parliament’s Committee of Enquiry into Freedom of Expression, parliamentarian Andrei Shevchenko deplored not only the increase in press freedom violations but also, and above all, the disturbing and challenging lack of reaction from the government. The data gathered by the organisation in the course of its monitoring of Ukraine confirms that there has been a significant increase in reports of press freedom violations since Viktor Yanukovych’s election as president in February. LEGISlaTIVE ISSUES The government’s desire to control journalists is reflected in the legislative domain. Reporters Without Borders visited Ukraine from 19 to 21 July in order to accomplish The Commission for Establishing Freedom the first part of an evaluation of the press freedom situation. of Expression, which was attached to the presi- It met national and local media representatives, members of press freedom dent’s office, was dissolved without explanation NGOs (Stop Censorship, Telekritika, SNUJ and IMI), ruling party and opposition parliamentarians and representatives of the prosecutor-general’s office. on 2 April by a decree posted on the president’s At the end of this initial visit, Reporters Without Borders gave a news conference website on 9 April. -

The Impact of Changes in Electoral Systems: a Comparative Analysis of the Local Election in Ukraine in 2006 and 2010

STUDIA VOL. 36 POLITOLOGICZNE STUDIA I ANALIZY Olena Yatsunska The impact of changes in electoral systems: a comparative analysis of the local election in Ukraine in 2006 and 2010 KEY WORDS: local government, local elections, proportional electoral system, majoritarian electoral system, mixed majoritarian-proportional electoral system, Ukraine STUDIA I ANALIZY Having gained independence in 1991 Ukraine, like most Central and East- ern European countries, faced the need for radical Constitutional reforms, with reorganization of local government figuring high in the agenda. Like other post-soviet countries, Ukraine had to decide on the starting point and like in the neighboring countries, democratic euphoria of the early 1990s got the upper hand: local authorities were elected on March 18, 1990, while the Law On Local People’s Deputies of Ukrainian SSR and Local Self-government was adopted by Verkhovna Rada of Ukrainian SSR on December 7, 1990. Ukrain- ian Researchers in the field of local government and its reforms concur with the opinion that the present dissatisfactory state of that institution was con- ditioned by the first steps made by Ukrainian Politicians at the beginning of the ‘transition’ period. Without clear perspective of reform, during more than 20 years of Independence, Ukrainian local government has abided dozens of laws, sometimes rather contradictory and has survived more than 10 stages of restructuring. Evolution of election legislation in Ukraine is demonstrated by Table 1. The table shows that since 1994 three electoral systems have been tested in Ukraine: 1, Majoritarian, 2, Proportional except elections to village and settlement councils and 3, ‘Mixed’ system (50% Majoritarian+50% Proportional). -

Ukraine by Oleksandr Sushko and Olena Prystayko

Ukraine by Oleksandr Sushko and Olena Prystayko Capital: Kyiv Population: 45.9 million GNI/capita (PPP), PPP: US$6,620 Source: The data above were provided by The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2012. Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Electoral Process 4.00 4.25 3.50 3.25 3.00 3.00 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.75 Civil Society 3.50 3.75 3.00 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 Independent Media 5.50 5.50 4.75 3.75 3.75 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.75 4.00 Governance* 5.00 5.25 n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a n/a National Democratic Governance n/a n/a 5.00 4.50 4.75 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.50 5.75 Local Democratic Governance n/a n/a 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.25 5.50 5.50 Judicial Framework and Independence 4.50 4.75 4.25 4.25 4.50 4.75 5.00 5.00 5.50 6.00 Corruption 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 5.75 6.00 Democracy Score 4.71 4.88 4.50 4.21 4.25 4.25 4.39 4.39 4.61 4.82 * Starting with the 2005 edition, Freedom House introduced separate analysis and ratings for national democratic governance and local democratic governance to provide readers with more detailed and nuanced analysis of these two important subjects. -

Diapositive 1

AND PRESENT The DEALBOOK 1st EDITION of Ukraine V 1.42 – UPDATED JULY 2015 2012-2014 THE DEAL BOOK OF UKRAINE About this report This unique research represents a comprehensive compilation of the majority of deals conducted on the Ukrainian IT and Internet market in 2012-2014. The report also covers some of the deals closed in 2010 and 2011. The report analyzes 250 deals involving more than 1,000 startups in Ukraine over the past four years. It is structured in four parts: I. In-depth analysis of investment activities, major investors and trends II. Detailed deal tables III. Opinions from leading investors IV. Entrepreneur stories This research is offered free of charge. It will be updated regularly and kept available gratis to all interested parties in order to draw to the vibrant Ukrainian innovation scene the attention it deserves. Inaccuracies & updates This is the first issue of the Deal Book of Ukraine. While we have done our best to provide accurate and complete information, we recognize the limits of such industry reporting – and will be pleased to receive any corrections, notices of inaccuracies or information on deals we may have missed. New and updated data will be included in the next publication, improving the level of detail and the quality of the report. Please submit corrections, updates and/or suggestions to [email protected]. Our thanks in advance for your assistance, which will make the next Deal Book a better resource for the investment community. Copyright policy The content of this report and its summaries is protected by copyright. -

Yushchenko Wins As Inauguration Is on Hold

INSIDE: • “2004: THE YEAR IN REVIEW” – pages 5-36 Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIII HE KRAINIANNo. 3 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 16, 2005 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine No celebrationsT yet,U W CEC announces final result: Yushchenko wins as inauguration is on hold by Andrew Nynka Kyiv Press Bureau KYIV – An official declaration by Ukraine’s Central Election Commission named Viktor Yushchenko the newly elected president of Ukraine, but since that announcement on January 10 there have been no mass celebrations here. Kyiv has been strangely quiet and the tent camps that have stood in front of the Presidential Administration Building and on Khreschatyk in the wake of the fraudulent November 21 election remain. Ukrainians throughout this city say there is nothing to celebrate until Mr. Yushchenko is officially inaugu- rated in the Verkhovna Rada as independent Ukraine’s third president. “I’m waiting. I’m not going anywhere until Yushchenko is inaugurated. We’ve seen all this in the past and it was overturned in the courts,” said Dimitri Leontiv, 74 a retiree from Chernihiv who has been liv- ing in the tent camp on the Khreschatyk since November 22. “We’ll celebrate when there is something to celebrate,” he added. Other Ukrainians here echoed Mr. Leontiv’s com- ments, saying they were happy with the CEC’s official announcement but hesitant to celebrate until the presi- AP/Sergei Chuzavkov dent-elect was sworn in. While Mr. Yushchenko’s Supporters of Viktor Yushchenko who was officially declared winner of Ukraine's presidential election, sign orange campaign color is still seen widely throughout his campaign poster after the official election results were announced at the Central Election Commission. -

Ukraine – 21 November 2004

NATO Parliamentary Assembly Assemblée parlementaire de l’OTAN INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Presidential Election (Second Round), Ukraine – 21 November 2004 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS Kyiv, 22 November 2004 - The International Election Observation Mission (IEOM) for the second round of the Ukrainian presidential election is a joint undertaking of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR), the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly (OSCE PA), the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE), the European Parliament (EP) and the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. This statement should be considered in conjunction with the IEOM’s statement released on 1 November 2004, after the first round of voting. It is issued prior to a full and final analysis of observers’ findings of the second round election day. Preliminary Conclusions As for the first round, the second round of the Ukrainian presidential election did not meet a considerable number of OSCE commitments and Council of Europe and other European standards for democratic elections. Despite a number of serious shortcomings being identified by the IEOM in its statement of 1 November, the authorities failed to take remedial action between the two rounds of voting to redress biased coverage on State media, misuse of State resources, and pressure on certain categories of voters to support the candidacy of Mr. Yanukovych. Overall, State executive authorities and the Central Election Commission (CEC) displayed a lack of will to conduct a genuine democratic election process. On election day, although voting was conducted in a generally calm manner, overall, observers’ assessed election day less favourably, particularly in the central and eastern regions, than 31 October. -

Political Party Development in Ukraine

www.gsdrc.org [email protected] Helpdesk Research Report Political party development in Ukraine Sarah Whitmore 25.09.2014 Question What has been the pattern of political party development in Ukraine over the last 10 years and how have these parties performed in recent elections? Contents 1. Overview 2. The pattern of party development in Ukraine 3. The main parties and their electoral performance, 2004-2013 4. Leading competitors in the 2014 parliamentary elections 5. References 1. Overview Political parties in Ukraine were first formed only in 1990, initially as formations based largely on former dissident groups with national-democratic orientation and the tendency to frequently split into separate parties. By the mid-1990s various regional financial industrial groups became involved in forming centrist parties to further their interests. All parties in Ukraine remain highly underdeveloped. Despite some seeming stabilisation of the main parties after the ‘orange revolution’ of 2004, the ‘Euromaidan revolution’ of 2013-14 and the departure of President Yanukovych from the political scene has prompted a thoroughgoing restructuring of the party space. The main competitors in the pre-term parliamentary elections due to take place in October 2014 now include a large number of new configurations and recently-formed electoral alliances. Nevertheless, despite the presence of new faces on parties’ electoral lists, the key players remain established politicians who are attempting to prove their ‘revitalisation’ by including Euromaidan civil society activists and officers from the Donbas conflict. Key political developments include: . Ukraine’s 7th parliamentary elections will take place according to a mixed electoral system where 225, or 50 per cent of seats, will be elected by a proportional party list system using closed party lists and allocating seats to parties obtaining over 5 per cent of the vote. -

Party of the Regions, Tymoshenko Bloc Top Polls in Parliamentary

INSIDE:• Map reveals election winners by oblast — page 3. • Voters in Kyiv and Lviv elect new mayors — page 3. • International observers assess Ukraine’s elections — page 5. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXXIV HE KRAINIANNo. 14 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 2, 2006 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine PartyT of the Regions,U Tymoshenko Bloc top polls inW parliamentary elections by Zenon Zawada Ms. Tymoshenko’s popularity has Oblast, which gave the most votes to Kyiv Press Bureau soared since the 2002 elections, when Socialist Party of Ukraine in 2002, and the her bloc earned 1.9 million votes, or the Kirovohrad Oblast, which the Communist KYIV – The Party of the Regions of support of 7 percent of the electorate. Party of Ukraine had previously won. CEC releases Ukraine emerged from the March 26 par- The Tymoshenko Bloc even won the liamentary elections with the most votes, Sumy Oblast, where Mr. Yushchenko but it was Yulia Tymoshenko who was final results was born and raised, winning 33 percent With 100 percent of the ballots crowned the winner. of the vote compared to 19 percent for counted, the Central Election Defying most expectations, her politi- Our Ukraine. Commission on Thursday evening, cal bloc placed second in voting, steam- The Tymoshenko Bloc also made March 30, released the following rollering over the Our Ukraine bloc and gains in regions that Our Ukraine could results of Ukraine’s parliamentary handing her rival and former boss Viktor never succeed in. elections of March 26. Yushchenko an embarrassing defeat. -

Diapositive 1

AND PRESENT The DEALBOOK 1ST EDITION – DEC. 2014 of Ukraine V 1.2 – UPDATED DEC. 20, 2014 2012-2014 THE DEAL BOOK OF UKRAINE About this report This unique research represents a comprehensive compilation of the majority of deals conducted on the Ukrainian IT and Internet market in 2012-2013. The report also covers some of the deals closed in 2010, 2011 and the first ten months of 2014. The report analyzes 250 deals involving more than 1,000 startups in Ukraine over the past four years. It is structured in four parts: I. In-depth analysis of investment activities, major investors and trends II. Detailed deal tables III. Opinions from leading investors IV. Entrepreneur stories This research is offered free of charge. It will be updated regularly and kept available gratis to all interested parties in order to draw to the vibrant Ukrainian innovation scene the attention it deserves. Inaccuracies & updates This is the first issue of the Deal Book of Ukraine. While we have done our best to provide accurate and complete information, we recognize the limits of such industry reporting – and will be pleased to receive any corrections, notices of inaccuracies or information on deals we may have missed. New and updated data will be included in the next publication, improving the level of detail and the quality of the report. Please submit corrections, updates and/or suggestions to [email protected]. Our thanks in advance for your assistance, which will make the next Deal Book a better resource for the investment community. Copyright policy The content of this report and its summaries is protected by copyright. -

Russia Cuts Off Gas Supplies to Ukraine Over Pricing Issues

InsIde: • “2008: THE YEAR IN REVIEW” – pages 5-37. HEPublished byKRAIN the Ukrainian National AssociationIAN Inc., a fraternal non-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXVIIT UNo. 2 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY W 11, 2009 $1/$2 in Ukraine Voice of America ends Russia cuts off gas supplies radio broadcasts to Ukraine to Ukraine over pricing issues by Zenon Zawada A joint statement issued by President Kyiv Press Bureau Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko on January 1 called for a price KYIV – In their biggest conflict ever, of $201 per 1,000 cubic meters and a natural Russian and Ukrainian natural gas officials gas transit rate of $2 for each 1,000 cubic failed to agree on prices for supplies and meters per 100 kilometers of Ukrainian transport, once again disrupting the vast pipeline. The Russian government wants to flow of natural gas into Europe and threat- keep the transit rate at $1.70 for 1,000 cubic ening economic crisis throughout the conti- meters transported per 100 kilometers. nent. As Russian and Ukrainian leaders hag- Gazprom, Russia’s government-owned gled over Ukraine’s price for natural gas and natural gas monopoly, cut off gas supplies to the price to use Ukraine’s pipelines – Ukraine the morning of January 1, setting Naftohaz Ukrayiny Chair Oleh Dubyna off cycling rounds of supply threats, accusa- spent several days fruitlessly negotiating tions of theft, bids, counter-bids and similar with Gazprom Chair Alexey Miller – posturing as part of negotiations that, for the European officials complained they were first time, extended beyond Christmas Day already suffering from the conflict.