Political Party Development in Ukraine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euromaidan Newsletter # 6 CIVIC SECTOR of EUROMAIDAN

CIVIC SECTOR OF EUROMAIDAN GRASSROOTS MOVEMENT EuroMaidan Newsletter # 6 Rise up, Ukraine! Protestors seize state administration buildings all over Ukraine January 25 and 26, 2014 . People all over Ukraine began http://goo.gl/hSnIGA taking over the Oblast (Region) Local State Businessmen of Crimea formed the initiative “For January January 2014 Administration buildings. In Western regions the State Crimea without Dictatorship” and announced their 8 2 Administrations have recognized the authority of the support for Maidan. Read more (in Russian) at - People’s Council created at Maidan in Kyiv. http://goo.gl/3o65u2 Protestors were blocked in their attempts to seize the January 26. Multiple journalists were injured in government buildings in Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhya, Zaporizhya on Jan. 26 as police cleaned out the square Chernihiv, and Kherson oblasts, while the Sumy and where about 10,000 protesters were trying to seize the #6. 24 Cherkasy districts were occupied for only a short time. oblast government's state administration building. Read In the East – in Zaporizhia, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, more details at http://goo.gl/LsaQSO Kharkiv - mass demonstrations are still being held near In Dnipropetrovsk the attempt to seize the state local administrations. See the map for details. Massive administration building was thwarted by police and hired repressions, tortures and arrests have been reported in thugs (“titushki”). In clashes with titushki people were these cities. Watch videos from the seizure of the state beaten, and journalists shot with traumatic weapons. administrations in Rivne, Khmelnytskyi, and Sumy at Watch video at http://goo.gl/E9q6MW Map of NEWSLETTER Ukraine showing: regions where oblast state administration s have been seized by citizens; mass rallies; and attempts at administration building seizure. -

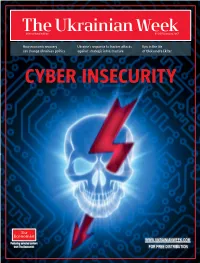

Cyber Insecurity

#1 (107) January 2017 How economic recovery Ukraine's response to hacker attacks Kyiv in the life can change Ukrainian politics against strategic infrastructure of Oleksandra Ekster CYBER INSECURITY WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION CONTENTS | 3 BRIEFING 4 Where’s the elite? Who can make the foundation of Ukraine’s transformed political machine POLITICS 8 A toxic environment: The present and future of the President’s party 10 Migration and mimicry: How much parties in Donetsk Oblast changed after the Maidan 12 Ride that wave: Political challenges of the possible economic recovery in 2017 16 Emerging communities: Decentralisation of Donetsk Oblast in the time of war ECONOMICS 18 Lessons learned: The benefits and flaws of PrivatBank transfer into state hands 20 Privatization, sanctions and security: How the Rosneft deal happened with the Russia sanctions in place NEIGHBOURS 24 Listen, liberal: Does Alexei Kudrin’s strategy to liberalise Russia’s economy stand a chance? 26 The unknown: Michael Binyon on what Europe expects from the presidency of Donald Trump 28 Nicolas Tenzer: “It makes no sense to negotiate with Putin” French political scientist on the prospects of ending the war in Ukraine, global and European security FOCUS 31 The other front: What cyber threats Ukraine has faced in the past two years 34 Shades of the Lviv underground: How Ukrainian hackers fight the cyber war SOCIETY 36 The invisible weapons: Ukraine’s role in the information warfare 38 The titans: Stories of people who build the future on a daily basis CULTURE & ARTS 46 The champion of Avant-Garde: The life and inspiration of Oleksandra Ekster 50 French films, Ukrainian Surrealism and contemporary theatre: The Ukrainian Week offers a selection of events to attend in the next month E-mail [email protected] www.ukrainianweek.com Tel. -

7 Political Corruption in Ukraine

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE π 7 (111) CONTENTS POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: ACTORS, MANIFESTATIONS, 2009 PROBLEMS OF COUNTERING (Analytical Report) ................................................................................................... 2 Founded and published by: SECTION 1. POLITICAL CORRUPTION AS A PHENOMENON: APPROACHES TO DEFINITION ..................................................................3 SECTION 2. POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: POTENTIAL ACTORS, AREAS, MANIFESTATIONS, TRENDS ...................................................................8 SECTION 3. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF COUNTERING UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES POLITICAL CORRUPTION ......................................................................33 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV SECTION 4. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS ......................................................... 40 ANNEX 1 FOREIGN ASSESSMENTS OF THE POLITICAL CORRUPTION Director General Anatoliy Rachok LEVEL IN UKRAINE (INTERNATIONAL CORRUPTION RATINGS) ............43 Editor-in-Chief Yevhen Shulha ANNEX 2 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SPECIFICITY, SCALE AND WAYS Layout and design Oleksandr Shaptala OF COUNTERING IN EXPERT ASSESSMENTS ......................................44 Technical & computer support Volodymyr Kekuh ANNEX 3 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SCALE AND WAYS OF COUNTERING IN PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS AND ASSESSMENTS ...................................49 This magazine is registered with the State Committee ARTICLE of Ukraine for Information Policy, POLITICAL -

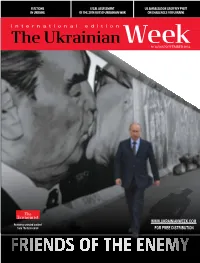

For Free Distribution

ELECTIONS LeGAL ASSESSMENT US AMBASSADOR GeOFFREY PYATT IN UKRAINE OF THE 2014 RuSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR ON CHALLENGES FOR UKRAINE № 14 (80) NOVEMBER 2014 WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION |CONTENTS BRIEFING Lobbymocracy: Ukraine does not have Rapid Response Elections: The victory adequate support in the West, either in of pro-European parties must be put political circles, or among experts. The to work toward rapid and irreversible situation with the mass media and civil reforms. Otherwise it will quickly turn society is slightly better into an equally impressive defeat 28 4 Leonidas Donskis: An imagined dialogue on several clichés and misperceptions POLITICS 30 Starting a New Life, Voting as Before: Elections in the Donbas NEIGHBOURS 8 Russia’s gangster regime – the real story Broken Democracy on the Frontline: “Unhappy, poorly dressed people, 31 mostly elderly, trudged to the polls Karen Dawisha, the author of Putin’s to cast their votes for one of the Kleptocracy, on the loyalty of the Russian richest people in Donetsk Oblast” President’s team, the role of Ukraine in his grip 10 on power, and on Russia’s money in Europe Poroshenko’s Blunders: 32 The President’s bloc is painfully The Bear, Master of itsT aiga Lair: reminiscent of previous political Russians support the Kremlin’s path towards self-isolation projects that failed bitterly and confrontation with the West, ignoring the fact that they don’t have a realistic chance of becoming another 12 pole of influence in the world 2014 -

Ukrainian Civil Society from the Orange Revolution to Euromaidan: Striving for a New Social Contract

In: IFSH (ed.), OSCE Yearbook 2014, Baden-Baden 2015, pp. 219-235. Iryna Solonenko Ukrainian Civil Society from the Orange Revolution to Euromaidan: Striving for a New Social Contract This is the Maidan generation: too young to be burdened by the experi- ence of the Soviet Union, old enough to remember the failure of the Orange Revolution, they don’t want their children to be standing again on the Maidan 15 years from now. Sylvie Kauffmann, The New York Times, April 20141 Introduction Ukrainian civil society became a topic of major interest with the start of the Euromaidan protests in November 2013. It has acquired an additional dimen- sion since then, as civil society has pushed for reforms following the ap- pointment of the new government in February 2014, while also providing as- sistance to the army and voluntary battalions fighting in the east of the coun- try and to civilian victims of the war. In the face of the weakness of the Ukrainian state, which is still suffering from a lack of political will, poor governance, corruption, military weakness, and dysfunctional law enforce- ment – many of those being in part Viktor Yanukovych’s legacies – civil so- ciety and voluntary activism have become a driver of reform and an import- ant mobilization factor in the face of external aggression. This contribution examines the transformation of Ukrainian civil society during the period between the 2004 Orange Revolution and the present day. Why this period? The Orange Revolution and the Euromaidan protests are landmarks in Ukraine’s post-independence state-building and democratiza- tion process, and analysis of the transformation of Ukrainian civil society during this period offers interesting findings.2 Following a brief portrait of Ukrainian civil society and its evolution, the contribution examines the rela- tionships between civil society and three other actors: the state, the broader society, and external actors involved in supporting and developing civil soci- ety in Ukraine. -

Searching for a Common Methodological Ground for the Study

Journal of Research in Personality 70 (2017) 27–44 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Research in Personality journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jrp Full Length Article Searching for a common methodological ground for the study of politicians’ perceived personality traits: A multilevel psycholexical approach ⇑ Oleg Gorbaniuk a,g, , Wiktor Razmus a, Alona Slobodianyk a, Oleksandr Mykhailych b, Oleksandr Troyanowskyj c, Myroslav Kashchuk d, Maryna Drako a, Albina Dioba e, Larysa Rolisnyk f a The John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland b National Aviation University, Kyiv, Ukraine c National University Odessa Law Academy, Odessa, Ukraine d Ukrainian Catholic University, Lviv, Ukraine e O.M. Beketov National University of Urban Economy in Kharkiv, Kharkiv, Ukraine f National Mining University, Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine g University of Zielona Gora, Zielona Gora, Poland article info abstract Article history: Received 21 November 2016 Ó 2017 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Accepted 16 May 2017 Available online 20 May 2017 1. Introduction their significance in determining political preferences (Caprara, Barbaranelli, & Zimbardo, 1997, 2002; Koppensteiner & For a fairly long time, research on political behavior have Grammer, 2010; Koppensteiner, Stephan, & Jäschke, 2015) have focused on the exploration of factors influencing voter decisions been based on the structure of personality traits from the five fac- (Blais & St-Vincent, 2011; Cwalina, Falkowski, Newman, & Vercic, tor model. The assumption that this model would describe politi- 2004; O’Cass, 2002; O’Cass & Pecotich, 2005; Schoen & cians’ perceived personality traits accurately was not confirmed Schumann, 2007; Wang, 2016). Out of many factors, the key one by research results (Caprara et al., 1997, 2002). -

Ukraine's Presidential Election Result

BULLETIN No. 21 (97) February 8, 2010 © PISM COMMENTARY Editors: Sławomir Dębski (Editor-in-Chief), Łukasz Adamski, Mateusz Gniazdowski, Beata Górka-Winter, Leszek Jesień, Agnieszka Kondek (Executive Editor), Łukasz Kulesa, Marek Madej, Ernest Wyciszkiewicz Ukraine’s Presidential Election Result Łukasz Adamski By securing a narrow majority of electoral support, Viktor Yanukovych triumphed over Yulia Tymoshenko in Ukraine’s presidential election. His contender may feel inclined to challenge the legitimacy of the vote, an effort in all probability doomed to failure. In the coming months Yanukovych is expected to oust Tymoshenko as Prime Minister and form a favouring government. With 48.95% of the popular vote, Yanukovych outdid rival Tymoshenko who scored slightly fewer votes, closing at 45.47%. The total of 4.4% of the ballots were cast against the two main contenders, thus giving the winner less than 50% of the votes. The insignificant difference in the number of ballots cast for each of the candidates may push Tymoshenko to seek an appeal requesting the courts to nullify the election result. In her election night address she failed to acknowledge Yanukovych’s victory. Even before the ballot her campaign team warned of Yanukovych’s fraudulent plans and advertised irregularities in the elections statute. What may underlie the potential attempt to undermine the election result will not be the desire for the ballot to be run again (a scenario having little chances of success in light of positive appraisal of the vote by monitoring teams) but rather the hope to persuade Yanukovych and his Party of Regions to seek compromise with the PM currently in office. -

Svoboda Party – the New Phenomenon on the Ukrainian Right-Wing Scene

OswcOMMentary issue 56 | 04.07.2011 | ceNTRe fOR eAsTeRN sTudies Svoboda party – the new phenomenon on the Ukrainian right-wing scene NTARy Me Tadeusz A. Olszański ces cOM Even though the national-level political scene in Ukraine is dominated by the Party of Regions, the west of the country has seen a progressing incre- ase in the activity of the Svoboda (Freedom) party, a group that combines tudies participation in the democratically elected local government of Eastern s Galicia with street actions, characteristic of anti-system groups. This party has brought a new quality to the Ukrainian nationalist movement, as it astern refers to the rhetoric of European anti-liberal and neo-nationalist move- e ments, and its emergence is a clear response to public demand for a group of this sort. The increase in its popularity plays into the hands of the Party of Regions, which is seeking to weaken the more moderate opposition entre for parties (mainly the Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc). However, Svoboda retains its c independence from the ruling camp. This party, in all likelihood, will beco- me a permanent and important player in Ukrainian political life, although its influence may be restricted to Eastern Galicia. NTARy Me Svoboda is determined to fight the tendencies in Ukrainian politics and the social sphere which it considers pro-Russian. Its attitude towards Russia and Russians, furthermore, is unambiguously hostile. In the case of Poland, ces cOM it reduces mutual relations almost exclusively to the historical aspects, strongly criticising the commemoration of the victims of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army’s (UPA) crimes. -

17Th Plenary Session

The Congress of Local and Regional Authorities 20 th SESSION CG(20)7 2 March 2011 Local elections in Ukraine (31 October 2010) Bureau of the Congress Rapporteur: Nigel MERMAGEN, United Kingdom (L, ILDG)1 A. Draft resolution....................................................................................................................................2 B. Draft recommendation.........................................................................................................................2 C. Explanatory memorandum..................................................................................................................4 Summary Following the official invitation from the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine to observe the local elections on 31 October 2010, the Congress appointed an observer delegation, headed by Gudrun Mosler-Törnström (R, Austria, SOC), Member and Vice-President of the State Parliament of Salzburg. Councillor Nigel Mermagen (L, UK, ILDG) was appointed Rapporteur. The delegation was composed of fifteen members of the Congress and four members of the EU Committee of the Regions, assisted by four members of the Congress secretariat. The delegation concluded, after pre-election and actual election observation missions, that local elections in Ukraine were generally conducted in a calm and orderly manner. It also noted with satisfaction that for the first time, local elections were held separately from parliamentary ones, as requested in the past by the Congress. No indications of systematic fraud were brought -

Will Ukraine's 2019 Elections Be a Turning Point?

Will Ukraine’s 2019 Elections Be a Turning Point? UNLIKELY, BUT DANGERS LURK PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 552 November 2018 Oleхiy Haran1 University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Petro Burkovsky2 National Institute for Strategic Studies (Kyiv) Next year, amid an ongoing conflict with Russia, sluggish economic recovery, and the rise of populism, Ukrainians will elect a new president (in March) and a new parliament (in October). Although the Ukrainian public is fragmented in its support of the six or seven frontrunners and parties, the outcome of both elections is not likely to bring radical change to Kyiv’s foreign and security policies—unless Russia decides to intervene, with or without violence. Ukrainians may be wary about Russian-backed activities, such as fostering a divisive referendum about conflict resolution in the Donbas or stirring up tensions between the government and ethnic minorities or Moscow patriarchate zealots. The country’s Western partners should not downplay the Kremlin’s potential interventions, nor should they overreact to any new configurations of Ukrainian political power. Perhaps the most important imperative for both Ukrainians and the West is to continue pushing for the separation of oligarchs from the levers of governance. Although much can change over the next five months, the current outlook is that political developments in 2019 are not expected to produce another major turning point in the colorful history of Ukraine. Poroshenko’s Legacy: Baking “Kyiv Cake” for Others? We argued in 2014 3 that three major challenges would define the course of President Petro Poroshenko’s presidency. First, he had to avoid actions that would lead to full- scale war with Russia or rampant civil war. -

Kremlin-Linked Forces in Ukraine's 2019 Elections

Études de l’Ifri Russie.Nei.Reports 25 KREMLIN-LINKED FORCES IN UKRAINE’S 2019 ELECTIONS On the Brink of Revenge? Vladislav INOZEMTSEV February 2019 Russia/NIS Center The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental, non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Taking an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. ISBN: 978-2-36567-981-7 © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2019 How to quote this document: Vladislav Inozemtsev, “Kremlin-Linked Forces in Ukraine’s 2019 Elections: On the Brink of Revenge?”, Russie.NEI.Reports, No. 25, Ifri, February 2019. Ifri 27 rue de la Procession 75740 Paris Cedex 15—FRANCE Tel. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00—Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Email: [email protected] Website: Ifri.org Author Dr Vladislav Inozemtsev (b. 1968) is a Russian economist and political researcher since 1999, with a PhD in Economics. In 1996 he founded the Moscow-based Center for Post-Industrial Studies and has been its Director ever since. In recent years, he served as Senior or Visiting Fellow with the Institut fur die Wissenschaften vom Menschen in Vienna, with the Polski Instytut Studiów Zaawansowanych in Warsaw, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Auswärtige Politik in Berlin, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and the Johns Hopkins University in Washington. -

Temptation to Control

PrESS frEEDOM IN UKRAINE : TEMPTATION TO CONTROL ////////////////// REPORT BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS JULLIARD AND ELSA VIDAL ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// AUGUST 2010 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// PRESS FREEDOM: REPORT OF FACT-FINDING VISIT TO UKRAINE ///////////////////////////////////////////////////////// 2 Natalia Negrey / public action at Mykhaylivska Square in Kiev in November of 2009 Many journalists, free speech organisations and opposition parliamentarians are concerned to see the government becoming more and more remote and impenetrable. During a public meeting on 20 July between Reporters Without Borders and members of the Ukrainian parliament’s Committee of Enquiry into Freedom of Expression, parliamentarian Andrei Shevchenko deplored not only the increase in press freedom violations but also, and above all, the disturbing and challenging lack of reaction from the government. The data gathered by the organisation in the course of its monitoring of Ukraine confirms that there has been a significant increase in reports of press freedom violations since Viktor Yanukovych’s election as president in February. LEGISlaTIVE ISSUES The government’s desire to control journalists is reflected in the legislative domain. Reporters Without Borders visited Ukraine from 19 to 21 July in order to accomplish The Commission for Establishing Freedom the first part of an evaluation of the press freedom situation. of Expression, which was attached to the presi- It met national and local media representatives, members of press freedom dent’s office, was dissolved without explanation NGOs (Stop Censorship, Telekritika, SNUJ and IMI), ruling party and opposition parliamentarians and representatives of the prosecutor-general’s office. on 2 April by a decree posted on the president’s At the end of this initial visit, Reporters Without Borders gave a news conference website on 9 April.