Bouquet of Barbed Wire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital and Culture

Capital and Culture An Investigation into New Labour cultural policy and the European Capital of Culture 2008. Mark Connolly Presented in fulfilment o f the requirements for the degree o f Doctor o f Philosophy at the University of Wales, Cardiff. December 2007 UMI Number: U584278 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584278 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Statements of Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed .. ...............(candidate) Date ........... STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD (insert MCh, MD, MPhil, PhD etc, as appropriate) Signed .. (candidate) Date M .U/L/.firk. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sourcesurces are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed (candidate) Date ....?. 9. /. I A./.^. STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. -

1 Sport Mega-Events and a Legacy of Increased

SPORT MEGA-EVENTS AND A LEGACY OF INCREASED SPORT PARTICIPATION: AN OLYMPIC PROMISE OR AN OLYMPIC DREAM? KATHARINE HELEN HUGHES A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Leeds Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. JANUARY 2013 1 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 7 Abstract ............................................................................................................................. 8 Student’s declaration ....................................................................................................... 10 List of Tables and Figures ................................................................................................ 11 List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 12 Preface ............................................................................................................................ 14 Chapter 1: Context of the study ....................................................................................... 17 1.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 17 1.2 Structure of the thesis ......................................................................................................... 19 1.3 Research aims and questions .......................................................................................... -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Tribune, December 3, 1943, in Paul Anderson ed. Orwell in Tribune (London: Politico’s, 2006), 57. 2. Margaret Tapster, WW2 People’s War, an online archive of wartime memories con- tributed by members of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/ 65/a5827665.shtml Accessed May 30, 2013. 3. Paul Addison, No Turning Back: The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2010); Peter Hennessy, Having It So Good: Britain in the Fifties (London: Allen Lane, 2006); David Kynaston Aus- terity Britain, 1945–51 (London, Berlin and New York: Bloomsbury, 2007); David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–1957 (London, Berlin, New York: Bloomsbury, 2009); Mark Donnelly, Sixties Britain: Culture, Society and Politics (Harlow: Pearson, 2005); Alwyn W. Turner, Crisis? What Crisis? Britain in the 1970s (London: Aurum Press, 2008); Andy Beckett, When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies (London: Faber and Faber, 2009); Dominic Sandbrook, Seasons in the Sun: The Battle for Britain, 1974–1979 (London: Allen Lane, 2012); Alwyn W. Turner, Rejoice! Rejoice! Britain in the 1980s (London: Aurum, 2010) and Andy McSmith, No Such Thing as Society: A History of Britain in the 1980s (London: Constable, 2011). 4. British and European resistance to American culture is expounded by Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style (London and New York: Routledge, 1979); Rob Kroes et al. Cultural Transmissions and Receptions: American Mass Culture in Europe (Amsterdam: VU University Press, 1993) and Rob Kroes, If You’ve Seen One, You’ve Seen the Mall: Europeans and American Mass Culture (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1996). -

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture

Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Dr Kate McNicholas Smith, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Professor Imogen Tyler, Lancaster University Department of Sociology Bowland North Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YN [email protected] Abstract The last decade has witnessed a proliferation of lesbian representations in European and North American popular culture, particularly within television drama and broader celebrity culture. The abundance of ‘positive’ and ‘ordinary’ representations of lesbians is widely celebrated as signifying progress in queer struggles for social equality. Yet, as this article details, the terms of the visibility extended to lesbians within popular culture often affirms ideals of hetero-patriarchal, white femininity. Focusing on the visual and narrative registers within which lesbian romances are mediated within television drama, this article examines the emergence of what we describe as ‘the lesbian normal’. Tracking the ways in which the lesbian normal is anchored in a longer history of “the normal gay” (Warner 2000), it argues that the lesbian normal is indicative of the emergence of a broader post-feminist and post-queer popular culture, in which feminist and queer struggles are imagined as completed and belonging to the past. Post-queer popular culture is depoliticising in its effects, diminishing the critical potential of feminist and queer politics, and silencing the actually existing conditions of inequality, prejudice and stigma that continue to shape lesbian lives. Keywords: Lesbian, Television, Queer, Post-feminist, Romance, Soap-Opera Lesbian Brides: Post-Queer Popular Culture Increasingly…. to have dignity gay people must be seen as normal (Michael Warner 2000, 52) I don't support gay marriage despite being a Conservative. -

The Naked Civil Servant

THE QUENTIN KIND: VISUAL NARRATIVE AND THE NAKED CIVIL SERVANT MARK ARMSTRONG PhD 2012 1 The Quentin Kind: Visual Narrative and The Naked Civil Servant Mark Armstrong A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the School of Arts and Social Sciences February 2012 2 Abstract This thesis offers a close reading of Quentin Crisp’s auto/biographical representations, most particularly The Naked Civil Servant. Published in 1968, Crisp’s autobiography was dramatized for Thames Television in 1975, a film that would prove seminal in the history of British broadcasting and something of a ‘quantum leap’ in the medium’s representation of gay lives. As an interpretative study, it offers a scope of visual and narrative analyses that assess Crisp’s cultural figure – his being both an ‘icon’ in gay history and someone against which gay men’s normative sense of masculinity could be measured. According to particular thematic concerns that allow for the correspondent reading of the visual and the literary auto/biographical text, this thesis considers the reception of that image and the binary meanings of fashioning it embodies. It explores not the detailed materiality of Crisp’s figure but its effects – the life that his fashioning determined and the fashioning of that life in textual discourse and media rhetoric. Observing Crisp as a performer of the auto/biographical, the following themes are addressed: the biopic, its tropes and ‘the body too much’; desire, otherness and the ‘great dark man’; the circumscribed life of the art school model; the ‘exile’ of a Chelsea bedsit; and the drag of a queer dotage. -

Summer Season May – August 2010

Summer Season May – August 2010 Into My Own Box Office: 01531 636147 Cinema 631338/633760 www.themarkettheatre.com Live Shows Fri 7 May 8pm £10 Pentabus Theatre Company from Shropshire TALES OF THE COUNTRY Brian Viner’s weekly despatches from the country are among the most popular features in the Independent newspaper. Having moved with his family from a terraced house in north London to a rambling grange in rural Herefordshire, their first 12 months were duly detailed in the wildly successful book Tales of the Country. Pentabus Theatre’s new show takes on the story of the Viner family bedding into their new life deep in the Herefordshire countryside. Full of hilarious incidents and wonderful characters, Tales of the Country is a beguiling chronicle of the pleasures and pitfalls that await a family from the city chasing a rural idyll. Brilliant: Sparkles with anecdotes, good jokes and hilarious observation – Daily Mail ; The excellent Pentabus – The Guardian. Sat 8 May 8pm £10/£8 students TRANSATLANTIC COLLECTION For one night only, Kentucky Fryd, The Roving Crows and Cowley Cowboys join forces to present a transatlantic musical extravaganza. Members from America, Ireland, France and the UK play original and traditional music blending Bluegrass, Folk, Country, Irish and Americana; featuring banjo, fiddle, guitars, banjolele, bass, drums, percussion, harmonica. Experience a musical and lyrical journey with fun and foot tapping guaranteed. Sat 15 May 8pm £12 GORDON GILTRAP One of the most innovative acoustic guitarists in the UK today, Gordon Giltrap has developed his own unique style, much copied, but never bettered. It is impossible not to be awestruck as he coaxes incredible melodies from his instruments; you almost suspect a second pair of hands! With over 40 years in the business, Gordon will satisfy fans with his most well loved hits, as well as explaining the history of his many different guitars. -

Framing the 2012 Olympics: a Content Analysis of International Newspaper Coverage of Female Athletes Jessica Giuggioli East Tennessee State University

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 5-2013 Framing the 2012 Olympics: A Content Analysis of International Newspaper Coverage of Female Athletes Jessica Giuggioli East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Mass Communication Commons, and the Public Relations and Advertising Commons Recommended Citation Giuggioli, Jessica, "Framing the 2012 Olympics: A Content Analysis of International Newspaper Coverage of Female Athletes" (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1108. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/1108 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Framing the 2012 Olympics: A Content Analysis of International Newspaper Coverage of Female Athletes _____________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of Communication East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Professional Communication _____________________ by Jessica Giuggioli May 2013 _____________________ John King, Chair Carrie Oliveira Gary Lhotsky Keywords: athletes, content analysis, framing theory, media ABSTRACT Framing the 2012 Olympics: A Content Analysis of International Newspaper Coverage of Female Athletes by Jessica Giuggioli The present content analysis was designed to identify the representation of female athletes in the media during the 2012 London Olympics. -

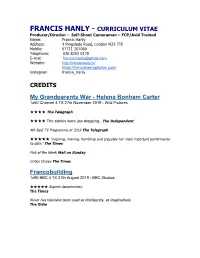

Francis Hanly

FRANCIS HANLY - CURRICULUM VITAE Producer/Director - Self-Shoot Cameraman – FCP/Avid Trained Name: Francis Hanly Address: 4 Ringslade Road, London N22 7TE Mobile: 07711 207060 Telephone: 020 8292 0178 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://francishanly.tv/ https://francishanlyphotos.com/ Instagram francis_hanly CREDITS My Grandparents War - Helena Bonham Carter 1x60 Channel 4 TX 27th November 2019 - Wild Pictures ★★★★ The Telegraph ★★★★ The stories were jaw dropping...The Independent 4th Best TV Programme of 2019 The Telegraph ★★★★★ ‘inspiring, moving, humbling and arguably her most important performance to date.’ The Times Pick of the Week Mail on Sunday Critics Choice The Times Francobuilding 1x90 BBC 4 TX 27th August 2019 - BBC Studios ★★★★★ Superb documentary The Times Never has television been used so intelligently, so imaginatively The Oldie Jargon - More Than You Ever Wanted To Know with Jonathan Meades 1x60 BBC 4 TX 27th May 2018 It’s good to have him back. Nobody else makes television like this. Radio Times Scathing lucid and hilarious. This erudite verbal and visual essay Observer A characteristically witty ribald and provocative essay The Times It’s ace! The Guardian There were so many more ideas in this hour than in the entire output, since its inception, of (say) The One Show that it was almost embarrassing. The Observer Blisteringly brutal, clever and hilarious. It manages to be visually interesting on what looks like a budget of 40 quid. The Guardian How on earth did Jonathan Meades on Jargon make it all the way to the screen? Were the people in BBC corporate responsibility (or whatever it's called) drunk or stoned or something, or did it unaccountably bypass their office all together? New Statesman This is a film that should be shown to all aspiring public figures before they disgrace themselves. -

January–June 2011 Contents

January–June 2011 CONTENTS 3–62 Simon & Schuster FICTION 63–130 Simon & Schuster NON-FICTION 131-145 Simon & Schuster ILLUSTRATED 146–153 Simon & Schuster MEDIA TIE-IN 154–155 Index 156 Contacts Key to Rights Codes – exClusive teRRitoRies W World WEL World english language BC British Commonwealth including Canada BCE British Commonwealth including Canada, EU UK United Kingdom, ireland and european open Market BXC British Commonwealth excluding Canada BXCA British Commonwealth excluding Canada, Australia, New Zealand BEXCA British Commonwealth including EU, excluding Canada, Australia, New Zealand BEXC British Commonwealth including EU, excluding Canada BCXA British Commonwealth including Canada, excluding Australia, New Zealand WXUSA World excluding USA WXUSI World excluding USA and india FICTION Simon & Schuster ‘Philippa Gregory is truly the mistress of the Philippa Gregory historical novel’ THE RED QUEEN SUNDAY EXPRESS The second novel in the spectacular The Cousins’ War series, The Red Queen continues the turbulent story of the Wars of the Roses, rich with intrigue and betrayal Married to a man twice her age, and a mother at only fourteen, Margaret Beaufort is determined to turn her lonely life into a triumph. She sets her heart on putting her son Henry on the throne of England at any cost. In a novel of conspiracy, passion and cold- hearted ambition, Philippa Gregory has brought to life the story of a proud and HIStorical FICtIoN determined woman who believes that she alone AUgUSt is destined, by her piety and lineage, to shape Paperback / ebook 978-1-84739-465-1 (PB) the course of history. 978-1-84737-978-8 (EB) 198x130 mm 432 pp PHILIPPA GREGORY is an internationally £7.99 Imprint: Simon & Schuster renowned writer of historical novels, including Agent: Simon & Schuster, Inc. -

January–June 2012 CONTENTS

January–June 2012 CONTENTS 3–21 Simon & Schuster HIGHLIGHTS 22–64 Simon & Schuster FICTION 65–118 Simon & Schuster NON-FICTION 119-125 Simon & Schuster ILLUSTRATED 126–127 Index 128 Contacts FICTION Highlights Karen Thompson Walker THE AGE OF MIRACLES KEY TO RIGHTS CODES – EXCLUSIVE TERRITORIES W World What if our 24-hour day grew longer, WEL World English Language first in minutes, then in hours, until day BC British Commonwealth including Canada becomes night and night becomes day? BCE British Commonwealth including Canada, EU What effect would this slowing have UK United Kingdom, Ireland and European Open Market on the world? On the birds in the sky, BXC British Commonwealth excluding Canada the whales in the sea, the astronauts in BXCA British Commonwealth excluding Canada, Australia, New Zealand space, and on an eleven-year-old girl, BEXCA British Commonwealth including EU, excluding Canada, Australia, New Zealand grappling with emotional changes in her BEXC British Commonwealth including EU, excluding Canada own life? BCXA British Commonwealth including Canada, excluding Australia, New Zealand One morning, Julia and her parents wake up in WXUSA World excluding USA their modest suburban home in California to WXUSI World excluding USA and India discover, along with the rest of the world, that the FICTION rotation of the earth is noticeably slowing. The JUNE enormity of this development is almost beyond Hardback 978-0-85720-723-4 comprehension. And yet, even if the world is, in 234x153 mm fact, coming to an end, as some assert, day-to-day 400 pp £12.99 life must go on. Julia, facing the loneliness and Agent: William Morris Agency (UK) Ltd.