A Dramaturgical Approach to the Performance of Selected Choral Works of Samuel Barber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Catalogue thématique des œuvres I. Musique orchestrale Année Œuvre Opus 1931 Ouverture « The School for Scandal » 5 1933 Music for a Scene from Shelley 7 1936 Symphonie in One Movement 9 Adagio pour orchestre à cordes [original : deuxième mouvement du 1938 11 Quatuor à cordes op.11, 1936] 1937 Essay for orchestra 12 1939 Concerto pour violon & orchestre 14 1942 Second Essay for Orchestra 17 1943 Commando March - 1944 Serenade pour orchestre à cordes [original pour quatuor à cordes, 1928] 1 1944 Symphonie n°2 19 1944 Capricorn Concerto pour flûte, hautbois, trompette & cordes 21 1945 Concerto pour violoncelle & orchestre 22 1945 Horizon, pour vents, timbales, harpe & orchestre à cordes - Medea (Serpent Heart) [version révisée Cave of the Heart, 1947 ; arr. Suite 1946 23 de ballet, 1947] 1952 Souvenirs [original : piano à quatre mains, 1951] 28 1953 Medea’s Meditation and Dance of Vengeance 23a 1960 Toccata Festiva pour orgue & orchestre 36 1960 Die Natali - Chorale Preludes for Christmas 37 1962 Concerto pour piano & orchestre 38 1964 Night Flight [arr. deuxième mouvement de la Symphonie n°2] 19a 1971 Fadograph of a Yestern Scene 44 1978 Third Essay for Orchestra 47 Canzonetta pour hautbois & orchestre à cordes [op. posth., complété 1978 48 et orchestré par Charles Turner] © 2009 Capricorn Association des amis de Samuel Barber II. Musique instrumentale Année Œuvre Opus 3 Sketches pour piano : Lovesong / To My Steinway n°220601 / 1923-24 - Minuet Fresh from West Chester (Some Jazzings) pour piano : Poison Ivy 1925-26 - / Let’s Sit it Out, I’d Rather Watch 1931 Interlude I (« Adagio for Jeanne ») pour piano - 1932 Interlude II pour piano - 1932 Suite for Carillon - 1942-44 Excursions pour piano 20 1949 Sonate pour piano 26 Souvenirs pour piano à quatre mains [arr. -

A Conductor's Guide to Twentieth-Century Choral-Orchestral Works in English

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9314580 A conductor's guide to twentieth-century choral-orchestral works in English Green, Jonathan David, D.M.A. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

Musical Narrative in Three American One-Act Operas with Libretti By

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Musical Narrative in Three American One- Act Operas with Libretti by Gian Carlo Menotti: A Hand of Bridge, The Telephone, and Introductions and Good-Byes Elizabeth Lena Smith Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MUSICAL NARRATIVE IN THREE AMERICAN ONE-ACT OPERAS WITH LIBRETTI BY GIAN CARLO MENOTTI: A HAND OF BRIDGE, THE TELEPHONE, AND INTRODUCTIONS AND GOOD-BYES By ELIZABETH LENA SMITH A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Elizabeth Lena Smith All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Elizabeth Lena Smith defended on March 14, 2005. ___________________________ Jane Piper Clendinning Professor Directing Dissertation ___________________________ Larry J. Gerber Outside Committee Member ___________________________ Michael H. Buchler Committee Member ___________________________ Matthew L. Lata Committee Member ___________________________ Matthew R. Shaftel Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To someone I once knew… iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to extend my appreciation to my advisor Prof. Jane Piper Clendinning for her continuous support and guidance through the preparation of this document as well as related proposals and presentations that preceded it. In every aspect of my doctoral experience, her encouragement and thoughtful counsel has proven invaluable. Also, my gratitude goes to Prof. Matthew Shaftel (whose doctoral seminar inspired this project) and Prof. -

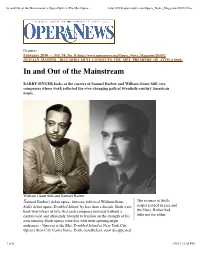

In and out of the Mainstream > Opera News > the Met Opera Guild

In and Out of the Mainstream > Opera News > The Met Opera ... http://www.operanews.com/Opera_News_Magazine/2010/2/Fea... Features February 2010 — Vol. 74, No. 8 (http://www.operanews.org/Opera_News_Magazine/2010/2 /ITALIAN_MASTER__RICCARDO_MUTI_CONDUCTS_THE_MET_PREMIERE_OF_ATTILA.html) In and Out of the Mainstream BARRY SINGER looks at the careers of Samuel Barber and William Grant Still, two composers whose work reflected the ever-changing path of twentieth-century American music. William Grant Still and Samuel Barber Samuel Barber's debut opera, Vanessa, followed William Grant The essence of Still's Still's debut opera, Troubled Island, by less than a decade. Both were output resided in jazz and hard-won labors of love that each composer initiated without a the blues. Barber had commission and ultimately brought to fruition on the strength of his little use for either. own tenacity. Both operas were hits with their opening-night audiences - Vanessa at the Met, Troubled Island at New York City Opera's then-City Center home. Both, nonetheless, soon disappeared 1 of 8 1/9/12 12:28 PM In and Out of the Mainstream > Opera News > The Met Opera ... http://www.operanews.com/Opera_News_Magazine/2010/2/Fea... from the active repertory. In the 1990s, Vanessa would be restored to a respected place in opera, a rebirth that Barber did not live to witness. For Still's Troubled Island, though, resurrection has never really come. As the centennial of Barber's birth approaches, it is intriguing to view him through the contrasting prism of William Grant Still. In many senses, no American composer of the twentieth century contrasts with Barber more. -

Gian Carlo Menotti

Gian Carlo Menotti Trio for violin, clarinet and piano Five songs for soprano & piano Cantilena e Scherzo for harp & string quartet Canti Della Lontananza for soprano & piano Gian Carlo Menotti Gian Carlo Menotti was born in Italy in 1911, but moved to America in 1928 to study at the Curtis Institute of Music, where he met his long-term partner, fellow-composer Samuel Barber. Throughout his life, Menotti felt a kinship with both his Italian heritage and the immediacy of American life. His musical style was direct and Trio for Violin, Clarinet & Piano emotional, drawing upon the influences of Puccini and Mussorgsky especially, but 01 Capriccio 5’09 encompassing a whole range of stylistic traits. Above all, Menotti was acutely 02 Romanza 5’59 conscious of reaching out to his audience. A prolific writer of stage works, his 1951 television opera Amahl and the Night Visitors brought opera to a new, wider public, and 03 Envoi 2’33 as co-founder of the Festival of Two Worlds in Spoleto in Italy, as well as its sister Spoleto Festival in South Carolina, Menotti lived out his belief that music is a gift to Five Songs be celebrated and shared by all. 04 i The Eternal Prisoner 2’05 Menotti’s Trio was commissioned by the Verdehr Trio, though it took more than one 05 ii The Idle Gift 1’41 request to motivate Menotti to write the work. Indeed, the Trio’s very existence is a 06 iii The Longest Wait 3’54 testament to the value of perseverance. Violinist Walter Verdehr first wrote to Menotti 07 iv My Ghost 3’47 in 1987, asking him to write a work for his chamber ensemble comprising violin, 08 v The Swing 3’41 clarinet and piano. -

Lyric Opera of Kansas City Announces Selection of 2018-2019 Resident Artists and Kicks Off Explorations Series with High Fidelity Opera

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Ellen McDonald (816) 213-4355 (c) [email protected] For Tickets: kcopera.org or (816) 471-7344 Lyric Opera of Kansas City Announces Selection of 2018-2019 Resident Artists and Kicks Off Explorations Series with High Fidelity Opera Resident Artist Program, led by World-Renowned Tenor and Teacher Vinson Cole includes Soprano Kaylie Kahlich, Mezzo-soprano Kelly Birch, Tenor Joseph Leppek, Baritone SeokJong Baek and Coach/Accompanist James Maverick High Fidelity Opera to showcase Resident Artists Sat. Nov. 17 at the Lyric Opera’s Michael and Ginger Frost Production Arts Building Kansas City, MO (Oct. 25, 2018) – General Director and CEO Deborah Sandler today announced the selection of the artists for the Resident Artist Program for the 2018-2019 season. They include soprano Kaylie Kahlich, mezzo-soprano Kelly Birch, tenor Joseph Leppek, baritone SeokJong Baek and coach/accompanist James Maverick. Led by Vinson Cole, UMKC Conservatory of Music and Dance faculty member and one of the leading artists of his generation, they will perform in various roles throughout the 2018-2019 season on the main stage at the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts as well as at community outreach and education events. During their residencies, in addition to appearing in mainstage roles, the Resident Artists will work with visiting guest artists, conductors and directors, participate in master classes, receive career coaching, study leading roles, make musical appearances in the community, and appear in their own intimate musical performances as a part of Lyric Opera of Kansas City’s Explorations series, which will focus on intimate gems of the vocal music repertoire. -

Scenes from Opera Theatre

LEON WILSON CLARK OPERA SERIES SHEPHERD SCHOOL OPERA presents an evening of SCENES FROM OPERA THEATRE directed and performed by students of Debra Dickinson at The Shepherd School of Music Sunday,April 18, and Monday, April 19, 1999 7:30 p.m. Wortham Opera Theatre RICE UNNERSITY PROGRAM A HAND OF BRIDGE Music by Samuel Barber Libretto by Gian-Carlo Menotti Sally: Kristin Anderson Bill: Eric Esparza Geraldine: Dawn Bennett David: Jameson James Director: Zachary Bruton Musical Director: Gregg Punswick A Hand ofBridge, Op. 35, is a chamber opera for four soloists and or chestra. It was written for the Festival of Two Worlds at Spoleto, Italy, to be part ofan evening ofshort operas and sketches, called ''Album Leaves," and was first performed on June 17, 1959. Written by Samuel Barber to a libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti, it is a little masterpiece in depth, unfold ing within its light comedy framework of two couples playing bridge, an acute and sad portrayal offour people alienated from one another, each living in his or her own private world. In spite of the brevity of the work, Barber and Menotti manage to create amazingly complex and intricate characters. Each character seeks escape from his or her confining and redundant life, symbolized by the games of bridge they play together every ~ night. Barber is represented at his best by music which embodies subtle romanticism with mild jazz overtones. cosi FAN TUTTE or THE SCHOOL FOR LOVERS Music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte Fiordiligi,from Ferrara, now living in Naples: Erin Wall Dorabella, her sister: Kristina Driskill Ferrando, army officer, lover of Dorabella: David Ray Guglielmo, army officer, lover of Fiordiligi: Brandon Gibson Don Alfonso, an old philosopher: Brady Knapp Despina, the sisters' serving maid: Ana Trevino Director: Joan Allouache Musical Director: Donald Doucet This opera is in two acts, composed in 1789-90, with libretto by Da Ponte and modeled on La Grotta di Tronfonio by Casti written for Salieri in 1785. -

Archives Concerts.Pdf

~ ~ ~ ~ ARCHIVES DES CONCERTS BARBER DANS LE MONDE DEPUIS 2009 ~ ~ ~ ~ © Association Capricorn, 2009-2014 Décembre 2013 20 La Jolla, All Hallows Catholic Church ..... [infos] Barber : Hermit Songs Œuvres de Hahn, Hildegard, Kuspa Katina Mitchell, soprano Peter Walsh, piano 15 Munich, Prinzregententheater ..... [infos] Barber : Adagio pour cordes Œuvres de Mozart, Liadov, Rossini, Dvořák Münchner Symphoniker, Jonathan Stockhammer 15 Vaudreuil-Dorion, Aréna ..... [infos] Barber : Agnus Dei Œuvres de Redner, Lully, Saint-Saëns, Holmès, Anderson Chœur Classique Vaudreuil-Soulanges, Jean-Pascal Hamelin 14 Moret-sur-Long, Eglise Notre-Dame-de-la-Nativité..... [infos] Barber : Reincarnations Œuvres de Brahms, Britten Ensemble vocal La Gioia, Laure-Marie Meyer 13 Lyon, Conservatoire national supérieur de musique et de danse ..... [infos] Barber : Mutations from Bach Œuvres de Copland, Cage, Glass, Nyman, Bernstein, Dahl Ensemble de cuivres, David Guerrier 13 Parme, Auditorium Niccolò Paganini ..... [infos] Barber : Concerto pour violon, Adagio pour cordes Brahms : Sérénade pour orchestre n°2 Mihaela Costa, violon Filarmonica Arturo Toscanini, Gaetano D'Espinosa 12 Paris, Fondation Singer-Polignac ..... [infos] Barber : Agnus Dei Œuvres de Stravinski, Ligeti, Messiaen, Poulenc, Britten, Schoenberg, Florentz, Kodaly Les Cris de Paris, Geoffroy Jourdain 11 Bruxelles, Grande Salle du Conservatoire royal ..... [infos] Barber : Capricorn Concerto Œuvres de Gorecki, Vasks, Rota Orchestre de chambre du Conservatoire royal de Bruxelles, Bernard Delire 11 Saint-Pétersbourg, Philharmonie ..... [infos] Barber : Concerto pour violon Œuvres de Gershwin, Chaplin, Elfman, Williams Igor Uryasch, violon Orchestre symphonique de Saint-Pétersbourg, Maxim Alexeev 10 Neuilly-sur-Seine, Théâtre des Sablons ..... [infos] 11 Gagny, Théâtre ..... [infos] 12 Vincennes, Auditorium ..... [infos] Barber : Adagio pour cordes Œuvres de Mozart, Britten Orchestre de chambre Nouvelle Europe, Nicolas Krauze 9 Melbourne, University/Melba Hall .... -

Three American Operas and Illinois Festival Opera, November 19, 2019

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData School of Music Programs Music 11-19-2019 Three American Operas and Illinois Festival Opera, November 19, 2019 Britannia Howe Stage Director Mikayla Mindiola Stage Management Dr. Justin Vickers Artistic Director Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Howe, Britannia Stage Director; Mindiola, Mikayla Stage Management; and Vickers, Dr. Justin Artistic Director, "Three American Operas and Illinois Festival Opera, November 19, 2019" (2019). School of Music Programs. 4314. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/somp/4314 This Performance Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music Programs by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Illinois State University Program Wonsook Kim College of Fine Arts Please silence all electronics for the duration of the concert. Thank you. School of Music Samuel Barber’s A Hand of Bridge, 1959 (libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti) David, baritone Jonathan Groebe _________________________________________ Geraldine, soprano Jessica Bella Bill, tenor Yung “Leo” Wang Sally, mezzo-soprano Lottie Heckman Three American Operas *Mikayla Mindiola (Understudy) Samuel Barber’s A Hand of Bridge Virgil Thomson’s Capital Capitals Aaron Gomez, conductor Ned Rorem’s Three Sisters Who Are Not Sisters Ye Eun “Grace” Eom, piano Virgil Thomson’s Capital Capitals, 1927 (libretto by Gertrude Stein) ILLINOIS FESTIVAL OPERA First Capital, tenor Yung “Leo” Wang Second Capital, tenor Zachary Bodnar Stage Director: Britannia Howe, MFA Directing Third Capital, baritone Dominic Regner Stage Management / Lights: Mikayla Mindiola Fourth Capital, bass Nathan Anton Artistic Director: Dr. -

Jeff Wright's Final Diss Draft for Committee

The Enlisted Composer: Samuel Barber’s Career, 1942-1945 Jeffrey Marsh Wright II A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Jocelyn R. Neal Jon W. Finson Mark Katz John L. Nádas Philip Vandermeer ©2010 Jeffrey Marsh Wright II ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT JEFFREY MARSH WRIGHT II: The Enlisted Composer: Samuel Barber’s Career, 1942-1945 (Under the direction of Jocelyn R. Neal) Throughout the 1920s and 1930s Samuel Barber emerged as one of America’s premier composers. In 1942, however, the trajectory of his flourishing career was thrown into question by the United States’ entrance into World War II, and the composer’s subsequent drafting into service. Being in the army nearly placed a moratorium on his compositional activity due to the time constraints of official duty. Yet Barber responded not only by maintaining his compositional momentum in the little free time that he had, but also by proposing new projects that would make it his sole, official duty to compose works that could be of potential use to the U.S. government. This dissertation examines the implications of a free artist being placed in an official role to write music at the request of the United States government. The idea of a composer writing music for a governmental patron is a notion normally reserved for composers in the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, but was a reality on the American front as well. -

83383 Vocal Promo4color

CONTENTS Includes releases from Fall 2001 through 2003 The Vocal Library.............................................................................................2 Joan Boytim Publications .................................................................................5 Art Song............................................................................................................6 Opera Collections.............................................................................................8 Opera Vocal Scores and Individual Arias ......................................................13 Ricordi Opera Full Scores...............................................................................15 Leonard Bernstein Theatre Publications........................................................16 Musical Theatre Collections ..........................................................................17 Theatre and Movie Vocal Selections .............................................................20 Solos for Children...........................................................................................23 Jazz and Standards...........................................................................................24 Solo Voice and Jazz Ensemble ........................................................................25 Jazz and Pop Vocal Instruction .......................................................................26 Popular Music .................................................................................................27 Collections................................................................................................27