Musical Narrative in Three American One-Act Operas with Libretti By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Four Semiotic Approaches to Musical Meaning: Markedness,

R. S. HATTEN « FOUR SEMIOTIC APPROACHES TO MUSICAL MEANING: MARKEDNESS, ... UDK 78:8 1'37 Robert S. Hatten School of Music, Indiana University Fakulteta za glasbo, Univerza v Indiani Four Semiotic Approaches to Musical Meaning: Markedness, Topics, Tropes, and Gesture Štirje semiotični pristopi h glasbenemu pomenu: zaznamovanost, topičnost, tropiranje in gestičnost Ključne besede: stil, zaznamovanost, topičnost, Keywords: style, markedness, topic, trope, tropiranje, gestičnost, Beethoven, Schubert gesture, Beethoven, Schubert POVZETEK SUMMARY Po kratkem pregledu razvoja glasbene semiotike v After a brief survey of music semiotic developments Združenih državah Amerike so predstavljeni štirje in the United States, I present four interrelated med seboj povezani pristopi, ki so rezultat mojega approaches based on my own work. Musical lastnega dela. Glasbeni pomen pri Beethovnu: Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, zaznamovanost, korelacija in interpretacija (1994) and Interpretation (1994) presents a new approach pomeni nov pristop h razumevanju sistematske to understanding the systematic nature of narave koreliranja med zvokom in pomenom, ki correlation between sound and meaning, based on sloni na konceptu glasbenega stila, kakor sta ga a concept of musical style drawn from Rosen (1972) izoblikovala Rosen (1972) in Meyer (1980, 1989) in and Meyer (1980, 1989), and expanded in Hatten kakor ga je razširil Hatten (1982). Zaznamovanost (1982). Markedness is a useful tool for explaining je koristno orodje za razlago asimetričnega the asymmetrical valuation of musical oppositions vrednotenja glasbenih nasprotij in načinov and their mapping onto cultural oppositions. This njihovega prenosa na področje kulturnih nasprotij. process of correlation as encoded in the style is Ta process koreliranja, ki je sicer zakodiran v stilu, further developed, along Peircean lines, by je možno razvijati naprej po Pierceovih smernicah, interpretation, as hermeneutically revealed in the in sicer z interpretacijo, kakor je v razpravi work. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

February 2008

21ST CENTURY MUSIC FEBRUARY 2008 INFORMATION FOR SUBSCRIBERS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC is published monthly by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. ISSN 1534-3219. Subscription rates in the U.S. are $84.00 per year; subscribers elsewhere should add $36.00 for postage. Single copies of the current volume and back issues are $10.00. Large back orders must be ordered by volume and be pre-paid. Please allow one month for receipt of first issue. Domestic claims for non-receipt of issues should be made within 90 days of the month of publication, overseas claims within 180 days. Thereafter, the regular back issue rate will be charged for replacement. Overseas delivery is not guaranteed. Send orders to 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC, P.O. Box 2842, San Anselmo, CA 94960. email: [email protected]. Typeset in Times New Roman. Copyright 2008 by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. This journal is printed on recycled paper. Copyright notice: Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC. INFORMATION FOR CONTRIBUTORS 21ST-CENTURY MUSIC invites pertinent contributions in analysis, composition, criticism, interdisciplinary studies, musicology, and performance practice; and welcomes reviews of books, concerts, music, recordings, and videos. The journal also seeks items of interest for its calendar, chronicle, comment, communications, opportunities, publications, recordings, and videos sections. Typescripts should be double-spaced on 8 1/2 x 11 -inch paper, with ample margins. Authors with access to IBM compatible word-processing systems are encouraged to submit a floppy disk, or e-mail, in addition to hard copy. -

Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Barber Piano Sonata In E-flat Minor, Opus 26 Comparative Survey: 29 performances evaluated, September 2014 Samuel Barber (1910 - 1981) is most famous for his Adagio for Strings which achieved iconic status when it was played at F.D.R’s funeral procession and at subsequent solemn occasions of state. But he also wrote many wonderful songs, a symphony, a dramatic Sonata for Cello and Piano, and much more. He also contributed one of the most important 20th Century works written for the piano: The Piano Sonata, Op. 26. Written between 1947 and 1949, Barber’s Sonata vies, in terms of popularity, with Copland’s Piano Variations as one of the most frequently programmed and recorded works by an American composer. Despite snide remarks from Barber’s terminally insular academic contemporaries, the Sonata has been well received by audiences ever since its first flamboyant premier by Vladimir Horowitz. Barber’s unique brand of mid-20th Century post-romantic modernism is in full creative flower here with four well-contrasted movements that offer a full range of textures and techniques. Each of the strongly characterized movements offers a corresponding range of moods from jagged defiance, wistful nostalgia and dark despondency, to self-generating optimism, all of which is generously wrapped with Barber’s own soaring lyricism. The first movement, Allegro energico, is tough and angular, the most ‘modern’ of the movements in terms of aggressive dissonance. Yet it is not unremittingly pugilistic, for Barber provides the listener with alternating sections of dreamy introspection and moments of expansive optimism. The opening theme is stern and severe with jagged and dotted rhythms that give a sense of propelling physicality of gesture and a mood of angry defiance. -

The 2009 Lotte Lenya Competition First Round

The 2009 Lotte Lenya Competition Lauren Worsham’s recent credits include Sophie in Master Class (Pa- permill Playhouse), Clara in The Light in the Piazza (Chamber Version - Kilbourn Hall, Eastman School of Music Weston Playhouse), Cunegonde in Candide (New York City Opera), Jerry Springer: The Opera (Carnegie Hall), Olive in The 25th Annual Putnam Saturday, 18 April 2009 County Spelling Bee (First National Tour). New York workshops/readings: Mermaid in a Jar, Le Fou at New Georges, The Chemist's Wife at Tisch, Mir- ror, Mirror at Playwright's Horizons, and Now I Ask You at Provincetown First Round Playhouse. Graduate of Yale University, 2005. Thanks for all the love and support from Bryan and Management 101. Most importantly, I owe it all to my amazing family. Proud member AEA! www.laurenworsham.com The Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, Inc. administers, promotes, and perpetuates the legacies of Kurt Weill and Lotte Lenya. It encourages broad dissemination and appreciation of Weill’s music through support of performances, productions, recordings, and scholarship; it fosters understanding of Weill’s and Lenya’s lives and work within diverse cultural contexts; and, building upon the legacies of both, it nurtures talent, particularly in the creation, performance, and study of musical theater in its various manifestations and media. Established in 1998 by the Kurt Weill Foundation for Music, the Lotte Lenya Competition provides a unique opportunity for talented young singer/actors to show their versatility in musical theater repertoire ranging from opera/operetta to contemporary Broadway, with Competition Administration, for the Kurt Weill Foundation: a focus on the varied works of Kurt Weill. -

From Femme Ideale to Femme Fatale: Contexts for the Exotic Archetype In

From Femme Idéale to Femme Fatale: Contexts for the Exotic Archetype in Nineteenth-Century French Opera A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Jessica H. Grimmer BM, University of Cincinnati June 2011 Committee chair: Jonathan Kregor, PhD i ABSTRACT Chromatically meandering, even teasing, Carmen’s Seguidilla proves fatally seductive for Don José, luring him to an obsession that overrides his expected decorum. Equally alluring, Dalila contrives to strip Samson of his powers and the Israelites of their prized warrior. However, while exotic femmes fatales plotting ruination of gentrified patriarchal society populated the nineteenth-century French opera stages, they contrast sharply with an eighteenth-century model populated by merciful exotic male rulers overseeing wandering Western females and their estranged lovers. Disparities between these eighteenth and nineteenth-century archetypes, most notably in treatment and expectation of the exotic and the female, appear particularly striking given the chronological proximity within French operatic tradition. Indeed, current literature depicts these models as mutually exclusive. Yet when conceptualized as a single tradition, it is a socio-political—rather than aesthetic—revolution that provides the basis for this drastic shift from femme idéale to femme fatale. To achieve this end, this thesis contains detailed analyses of operatic librettos and music of operas representative of the eighteenth-century French exotic archetype: Arlequin Sultan Favorite (1721), Le Turc généreux, an entrée in Les Indes Galantes (1735), La Recontre imprévue/Die Pilgrime von Mekka (1764), and Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1782). -

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27Th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director

THEOOOPER~ONFORUM November 14, 1980, Spm THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director MEET THE MODERNS 1: MUSIC + DRAMA two one-act operas THE CRY OF CLYTAEMNESTRA THE EGG Music by John Eaton an operatic riddle Libretto by Patrick Creagh Music and Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti New York premiere New York premiere RICHARD DUNCAN, conductor LUKAS FOSS, conductor Staging by Maurice Edwards Staging by Maurice Edwards Lighting by William Mintzer Lighting by William Mintzer Sound Co-ordinator: Lonnie Juli Costumes by Constance Mellen Cast Cast (in o rder of appearance) (in o rder of appearance) ClytaernJlt'~tra Quec•11 o{ Ar,J~e>S . elcla elson Manuel ................................... Martin Strother lphygene1a eldest dau,J~hter o{ C/ytaemnestra St Simeon Stylites .............................joseph Levitt !111(/ A.I!Cllll£'11111011 . • • • . • . • Sally Wolf BasJIJssa Empress o{ ByzantiUm ( Pnde} . ............ Edith Diggory Agamemnon KJII,JI of ArJioS . • . • • . Tim o ble Areobindus. {avonte o{the Bas111ssa (Lust} .......... Steven Nelson Ody~seus . Ri chard Walker Gourmantus, the cook (Gluttony} . ....... ........ Ted Adkins Menelaus . ·- . Brian Trego Eunuch of the Sacred Cubicle !Slot hi ............ Richard Walker DJOilll'tks . Martin Strother Pachomius. the treasurer (A vance} . .................. Jon Fay TnKer . Steven Nelson Sister of the BasJIJssa !Envyl . ...... ............... Paula Redd Calcha~. HlJih Pnest. joseph Levitt Julian, Capt am o{ the Guard (Anger} (silent role} . .. ..... Brian Trego Acl11llcs . .Jon Fay Beggar Woman . ... .............. Sarah Miller Electra. dauxhter o{ C/ytaem11estra and !Chorusl ............ Axamemncm. as a ch1ld . ................. .. ....... Abby Tate Members of the Basi IIssa's Court Sally Wolf, Martha Waltman Rebecca Field, Glenn Siebert, Colenton Freeman Orestes. so11 o{ Clytaem>lestra and Agamemnon, as a child . -

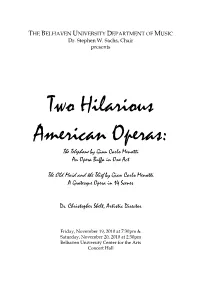

The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti a Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Two Hilarious American Operas: The Telephone by Gian Carlo Menotti An Opera Buffa in One Act The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti A Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes Dr. Christopher Shelt, Artistic Director Friday, November 19, 2010 at 7:30pm & Saturday, November 20, 2010 at 2:30pm Belhaven University Center for the Arts Concert Hall BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC MISSION STATEMENT The Music Department seeks to produce transformational leaders in the musical arts who will have profound influence in homes, churches, private studios, educational institutions, and on the concert stage. While developing the God-bestowed musical talents of music majors, minors, and elective students, we seek to provide an integrative understanding of the musical arts from a Christian world and life view in order to equip students to influence the world of ideas. The music major degree program is designed to prepare students for graduate study while equipping them for vocational roles in performance, church music, and education. The Belhaven University Music Department exists to multiply Christian leaders who demonstrate unquestionable excellence in the musical arts and apply timeless truths in every aspect of their artistic discipline. The Music Department would like to thank our many community partners for their support of Christian Arts Education at Belhaven University through their advertising in “Arts Ablaze 2010-2011” (should be published and available on or before September 30, 2010). Special thanks tonight to Bo-Kays Florist for our reception table flowers. It is through these and other wonderful relationships in the greater Jackson community that makes an afternoon like this possible at Belhaven. -

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Catalogue thématique des œuvres I. Musique orchestrale Année Œuvre Opus 1931 Ouverture « The School for Scandal » 5 1933 Music for a Scene from Shelley 7 1936 Symphonie in One Movement 9 Adagio pour orchestre à cordes [original : deuxième mouvement du 1938 11 Quatuor à cordes op.11, 1936] 1937 Essay for orchestra 12 1939 Concerto pour violon & orchestre 14 1942 Second Essay for Orchestra 17 1943 Commando March - 1944 Serenade pour orchestre à cordes [original pour quatuor à cordes, 1928] 1 1944 Symphonie n°2 19 1944 Capricorn Concerto pour flûte, hautbois, trompette & cordes 21 1945 Concerto pour violoncelle & orchestre 22 1945 Horizon, pour vents, timbales, harpe & orchestre à cordes - Medea (Serpent Heart) [version révisée Cave of the Heart, 1947 ; arr. Suite 1946 23 de ballet, 1947] 1952 Souvenirs [original : piano à quatre mains, 1951] 28 1953 Medea’s Meditation and Dance of Vengeance 23a 1960 Toccata Festiva pour orgue & orchestre 36 1960 Die Natali - Chorale Preludes for Christmas 37 1962 Concerto pour piano & orchestre 38 1964 Night Flight [arr. deuxième mouvement de la Symphonie n°2] 19a 1971 Fadograph of a Yestern Scene 44 1978 Third Essay for Orchestra 47 Canzonetta pour hautbois & orchestre à cordes [op. posth., complété 1978 48 et orchestré par Charles Turner] © 2009 Capricorn Association des amis de Samuel Barber II. Musique instrumentale Année Œuvre Opus 3 Sketches pour piano : Lovesong / To My Steinway n°220601 / 1923-24 - Minuet Fresh from West Chester (Some Jazzings) pour piano : Poison Ivy 1925-26 - / Let’s Sit it Out, I’d Rather Watch 1931 Interlude I (« Adagio for Jeanne ») pour piano - 1932 Interlude II pour piano - 1932 Suite for Carillon - 1942-44 Excursions pour piano 20 1949 Sonate pour piano 26 Souvenirs pour piano à quatre mains [arr.