Barber Piano Sonata in E-Flat Minor, Opus 26

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Formal Analytical Approach Was Utilized to Develop Chart Analyses Of

^ DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 970 24 HE 000 764 .By-Hanson, John R. Form in Selected Twentieth-Century Piano Concertos. Final Report. Carroll Coll., Waukesha, Wis. Spons Agency-Office of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. Bureauof Research. Bureau No-BR-7-E-157 Pub Date Nov 68 Crant OEC -0 -8 -000157-1803(010) Note-60p. EDRS Price tvw-s,ctso HC-$3.10 Descriptors-Charts, Educational Facilities, *Higher Education, *Music,*Music Techniques, Research A formal analytical approach was utilized to developchart analyses of all movements within 33 selected piano concertoscomposed in the twentieth century. The macroform, or overall structure, of each movement wasdetermined by the initial statement, frequency of use, andorder of each main thematic elementidentified. Theme groupings were then classified underformal classical prototypes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (ternary,sonata-allegro, 5-part or 7-part rondo, theme and variations, and others), modified versionsof these forms (three-part design), or a variety of free sectionalforms. The chart and thematic illustrations are followed by a commentary discussing each movement aswell as the entire concerto. No correlation exists between styles andforms of the 33 concertos--the 26 composers usetraditional,individualistic,classical,and dissonant formsina combination of ways. Almost all works contain commonunifying thematic elements, and cyclicism (identical theme occurring in more than1 movement) is used to a great degree. None of the movements in sonata-allegroform contain double expositions, but 22 concertos have 3 movements, and21 have cadenzas, suggesting that the composers havelargely respected standards established in theClassical-Romantic period. Appendix A is the complete form diagramof Samuel Barber's Piano Concerto, Appendix B has concentrated analyses of all the concertos,and Appendix C lists each movement accordog to its design.(WM) DE:802 FINAL REPORT Project No. -

Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition Edward Charity Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected]

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Summer 6-30-2014 Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition Edward Charity Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp Recommended Citation Charity, Edward, "Bach, Barber, and Brahms: Masters of Emotive Violin Composition" (2014). Research Papers. Paper 551. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp/551 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Research Papers by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION by Edward Charity B.M., Northwestern State University, 2011. A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Music Department of Music in the Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale August 2014 RESEARCH PAPER APPROVAL BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION By Edward Charity A Research Paper Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music in the field of Music Performance Approved by: Michael Barta, Chair Eric Lenz Jacob Tews Graduate School Southern Illinois University Carbondale June 28, 2014 AN ABSTRACT OF THE RESEARCH PAPER OF Edward Charity, for the Master of Music degree in Music Performance, presented on June 30, 2014, at Southern Illinois University Carbondale. TITLE: BACH, BARBER, AND BRAHMS: MASTERS OF EMOTIVE VIOLIN COMPOSITION MAJOR PROFESSOR: Michael Barta Three seminal works of the violin repertory will be examined: J.S. -

VANESSA Composer: Samuel Barber Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti After a Story by Isak Dinesen in Seven Gothic Tales

VANESSA Composer: Samuel Barber Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti after a story by Isak Dinesen in Seven Gothic Tales Vanessa has spent twenty years in her country house after being left by her lover, Anatol; she has kept the house shut up, with all of the mirrors covered. Her mother, the Old Baroness, will not speak to her; her only companion is her niece, Erika. As the opera opens, they are preparing for the arrival of Anatol. He is sighted coming towards the house, and Vanessa sends everyone else away; as soon as he arrives at the door, she declares her love for him--then faints when she discovers that the man on the doorstep is not her lover. He is, he explains to Erika, that Anatol's son; he has come to meet the woman whose name haunted his father and mother. The Anatol that Vanessa knew has died. Anatol, left alone with Erika, seduces her; the next day, after Erika learns that he has been making advances to Vanessa, she confronts him; he offers to marry her, but, offended by the flippancy with which he has proposed, and worried about Vanessa, rejects him. At the party where Vanessa and Anatol's engagement is announced, Erika reveals to the Old Baroness that she is pregnant with Anatol's child. She runs away from the house and causes herself to miscarry; a search party sent out by Vanessa brings her back. Vanessa, still unaware of Anatol's liason with Erika, marries him, and they leave together. Erika, left alone in the house with her grandmother, who now will not speak to her, orders the mirrors covered again and the gates closed and locked, just as before. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Knoxville: Summer of 1915” Danielle E

Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 19 Article 12 2015 Musical and Cultural Significance in Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” Danielle E. Kluver University of Nebraska at Kearney Follow this and additional works at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kluver, Danielle E. (2015) "Musical and Cultural Significance in Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915”," Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 19 , Article 12. Available at: https://openspaces.unk.edu/undergraduate-research-journal/vol19/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Undergraduate Research & Creative Activity at OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of OpenSPACES@UNK: Scholarship, Preservation, and Creative Endeavors. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musical and Cultural Significance in Samuel Barber’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” Danielle E. Kluver INTRODUCTION “We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child” (Agee 3). These first words of James Agee’s prose poem “Knoxville: Summer of 1915,” introduce the reader to a world of his youth – rural Tennessee in the early part of the century. Agee’s highly descriptive and lyrical language in phrases such as “these sweet pale streamings in the light out their pallors,” (Agee 5) invites the reader to use all his senses and become enveloped in the inherent music of the language. Is it any wonder that upon reading Agee’s words, composer Samuel Barber should be drawn into this narrative that enlivens the senses and touches the heart with its complexity of human emotions told through the recollections of childhood from a time of youth and innocence. -

SINCE 1945: a SURVEY May, 1971

/A/8 THE SOLO PIANO SONATA IN THE UNITED STATES SINCE 1945: A SURVEY THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Rebecca Jane Edge, B. M. Denton, Texas May, 1971 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. ........... ..... iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . * * . History of the Term "Sonata" Problems of the Modern Sonata II. THE PIANO SONATA IN THE UNITED STATES . 8 Before 1900 1900-1945 1945-1970 Trends in the Contemporary Sonata III. BRIEF ANALYSES OF EIGHT REPRESENTATIVE PIANO SONATAS WRITTEN BETWEEN 1945-1970 . 19 Samuel Barber, Sonata, Op. 26 John Cage, Sonatas and Interludes Elliott Carter, Piano Sonata Paul Creston, Sonata, Op. 9 Norman Dello Joio, Piano Sonata #L Alan Hovhaness, Poseidon Sonata Peter Mennin, Sonata for Piano Vincent Persichetti, Piano Sonata #2 APPENDIXA . 157 BIBLIOGRAPHY .0 ..9.. 0.. 0.. 9.. 0.. 0.61 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Beethoven Sonata in CM, Op. 53, first movement, measures 1-4 . 16 2. Roger Sessions Second Piano Sonata, first movement, measures 1-4W. .17 3. Samuel Barber Sonata, Op. 26, first move- ment, measures 1, 21, 17, 45-. 20 4. Samuel Barber Sonata, Op. 26, first move- ment, measure 9 . 21 5. Samuel Barber Sonata, Op. 26, third move- ment, measures1-5 . 23 6. Samuel Barber Sonata, Op. 26, fourth move- ment, measures 1-3*. 23 7. John Cage Sonatas and Interludes, "Sonata VIII," measures 2, 8-10 .... *. ... .*. .. 28 8. John Cage Sonatas and Interludes, "Sonata IV" . 29 9. Elliott Carter Piano Sonata, first movement, measures1-3, 15, 83o.. -

Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017

AAP: Music American nostalgia: Samuel Barber (1910-81), Aaron Copland (1910-90), and Charles Ives (1874-1954) – December 11, 2017 Aaron Copland • Parents immigrated to the US and opened a furniture store in Brooklyn • Youngest of five children • Began studying piano at age 13 • Studied in Paris with Nadia Boulanger (1887-1979) • The school of music at CUNY Queens College is named after him: Aaron Copland School of Music Career: • Composed – musical style incorporates Latin American (Brazilian, Cuban, Mexican), Jewish, Anglo-American, and African-American (jazz) sources • Conducted (1958-78) • Wrote essays about music • Visiting teaching positions (New School for Social Research, Henry Street Settlement, Harvard University) • Public lectures (Harvard’s Norton Professor of Poetics, 1951-52) Copland organized concerts that promoted the music of his peers: Marc Blitzstein (1905-64) Roy Harris (1898-1979) Paul Bowles (1910-99) Charles Ives (1874-1954) Henry Brant (1913-2008) Walter Piston (1894-1976) Carlos Chávez (1899-1978) Carl Ruggles (1876-1971) Israel Citkowitz (1909-74) Roger Sessions (1896-1985) Vivian Fine (1913-2000) Virgil Thomson (1896-1989) Copland was a mentor to younger composers: Leonard Bernstein (1918-90) Irving Fine (1914-62) David del Tredici (b. 1937) Lukas Foss (1922-2009) David Diamond (1915-2005) Barbara Kolb (b. 1939) Jacob Druckman (1928-96) William Schuman (1910-92) Elliott Carter (1908-2012) AAP: Music Selected works Orchestra Ballets (also published as orchestral suites) Music for the Theatre (1925) Billy the Kid -

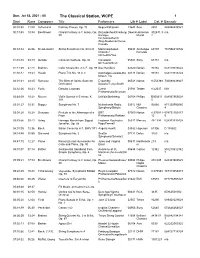

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sun, Jul 18, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 11:00 Schumann Fantasy Pieces, Op. 73 Segev/Pohjonen 13643 Avie 2389 822252238921 00:13:4518:34 Beethoven Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. Bezuidenhout/Freiburg DownloadHarmonia 902431.3 n/a 80 Baroque Mundi 2 Orchestra/Zurich Zing-Akademie/Heras- Casado 00:33:34 26:06 Mendelssohn String Symphony No. 08 in D Metamorphosen 05480 Archetype 60107 701556010726 Chamber Records Orchestra/Yoo 01:01:1009:19 Dvorak Carnival Overture, Op. 92 Cleveland 05021 Sony 63151 n/a Orchestra/Szell 01:11:2927:48 Brahms Cello Sonata No. 2 in F, Op. 99 Diaz/Sanders 02520 Dorian 90165 053479016522 01:40:47 19:24 Haydn Piano Trio No. 43 in C Kalichstein-Laredo-Ro 02473 Dorian 90164 053479016423 binson Trio 02:01:4129:45 Rameau The Birth of Osiris (Suite for Ensemble 06541 Naxos 8.553388 730099438827 Orchestra) Savaria/Terey-Smith 02:32:26 10:43 Fucik Danube Legends Czech 01781 Teldec 8.42337 N/A Philharmonic/Neuman 02:44:0915:48 Mozart Violin Sonata in E minor, K. Uchida/Steinberg 04768 Philips B000411 028947565628 304 5 03:01:27 35:31 Dopper Symphony No. 7 Netherlands Radio 03512 NM 92060 871330992060 Symphony/Bakels Classics 4 03:38:2810:28 Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a BRT 07909 Naxos 8.570011- 074731300117 Faun Philharmonic/Rahbari 12 0 03:49:56 09:43 Grieg Homage March from Sigurd Eastman Rochester 05011 Mercury 434 394 028943439428 Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Pops/Fennell 04:01:0912:36 Bach Italian Concerto in F, BWV 971 Angela Hewitt 03592 Hyperion 67306 D 138602 04:14:4530:55 Diamond Symphony No. -

Defining Musical Americanism: a Reductive Style Study of the Piano Sonatas of Samuel Barber, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, and Charles Ives

Defining Musical Americanism: A Reductive Style Study of the Piano Sonatas of Samuel Barber, Elliott Carter, Aaron Copland, and Charles Ives A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music by Brendan Jacklin BM, Brandon University, 2011 MM, Bowling Green State University, 2013 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract This document includes a reductive style study of four American piano sonatas premiered between 1939 and 1949: Piano Sonata No. 2 “Concord” by Charles Ives, Piano Sonata by Aaron Copland, Piano Sonata by Elliott Carter, and Piano Sonata, Op. 26 by Samuel Barber. Each of these sonatas represents a different musical style and synthesizes traditional compositional techniques with native elements. A reductive analysis ascertains those musical features with identifiable European origins, such as sonata-allegro principle and fugue, and in doing so will reveal which musical features and influences contribute to make each sonata stylistically American. While such American style elements, such as jazz-inspired rhythms and harmonies, are not unique to the works of American composers, I demonstrate how the combination of these elements, along with the extent each composer’s aesthetic intent in creating an American work, contributed to the creation of an American piano style. i Copyright © 2017 by Brendan Jacklin. All rights reserved. ii Acknowledgments I would first like to offer my wholehearted thanks to my advisor, Dr. bruce mcclung, whose keen suggestions and criticisms have been essential at every stage of this document. -

The Increasing Expressivities in Slow Movements of Beethoven's Piano

The Increasing Expressivities in Slow Movements of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: Op. 2 No. 2, Op. 13, Op. 53, Op. 57, Op. 101 and Op. 110 Li-Cheng Hung A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Robin McCabe, Chair Craig Sheppard Carole Terry Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2019 Li-Cheng Hung University of Washington Abstract The Increasing Expressivities in Slow Movements of Beethoven’s Piano Sonatas: Op. 2 No. 2, Op. 13, Op. 53, Op. 57, Op. 101 and Op. 110 Li-Cheng Hung Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Robin McCabe School of Music Ludwig van Beethoven’s influential status is not only seen in the keyboard literature but also in the entire music world. The thirty-two piano sonatas are especially representative of his unique and creative compositional style. Instead of analyzing the structure and the format of each piece, this thesis aims to show the evolution of the increasing expressivity of Beethoven’s music vocabulary in the selected slow movements, including character markings, the arrangements of movements, and the characters of each piece. It will focus mainly on these selected slow movements and relate this evolution to changes in his life to provide an insight into Beethoven himself. The six selected slow movements, Op. 2 No. 2, Op.13 Pathétique, Op. 53 Waldstein, Op. 57 Appassionata, Op. 101 and Op. 110 display Beethoven’s compositional style, ranging from the early period, middle period and late period. -

In and out of the Mainstream > Opera News > the Met Opera Guild

In and Out of the Mainstream > Opera News > The Met Opera ... http://www.operanews.com/Opera_News_Magazine/2010/2/Fea... Features February 2010 — Vol. 74, No. 8 (http://www.operanews.org/Opera_News_Magazine/2010/2 /ITALIAN_MASTER__RICCARDO_MUTI_CONDUCTS_THE_MET_PREMIERE_OF_ATTILA.html) In and Out of the Mainstream BARRY SINGER looks at the careers of Samuel Barber and William Grant Still, two composers whose work reflected the ever-changing path of twentieth-century American music. William Grant Still and Samuel Barber Samuel Barber's debut opera, Vanessa, followed William Grant The essence of Still's Still's debut opera, Troubled Island, by less than a decade. Both were output resided in jazz and hard-won labors of love that each composer initiated without a the blues. Barber had commission and ultimately brought to fruition on the strength of his little use for either. own tenacity. Both operas were hits with their opening-night audiences - Vanessa at the Met, Troubled Island at New York City Opera's then-City Center home. Both, nonetheless, soon disappeared 1 of 8 1/9/12 12:28 PM In and Out of the Mainstream > Opera News > The Met Opera ... http://www.operanews.com/Opera_News_Magazine/2010/2/Fea... from the active repertory. In the 1990s, Vanessa would be restored to a respected place in opera, a rebirth that Barber did not live to witness. For Still's Troubled Island, though, resurrection has never really come. As the centennial of Barber's birth approaches, it is intriguing to view him through the contrasting prism of William Grant Still. In many senses, no American composer of the twentieth century contrasts with Barber more. -

Formal Mixture in the Sonata-Form Movements of Middle- and Late-Period Beethoven James S

Document generated on 09/27/2021 3:30 a.m. Intersections Canadian Journal of Music Revue canadienne de musique Formal Mixture in the Sonata-Form Movements of Middle- and Late-Period Beethoven James S. MacKay Contemplating Caplin Article abstract Volume 31, Number 1, 2010 Modal mixture is defined as a local colouration of a diatonic progression by borrowing tones or chords from the parallel major or minor tonality. In his URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1009287ar efforts to expand tonal resources, Beethoven took this technique further: he DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1009287ar borrowed large-scale tonal processes from a composition’s parallel tonality, a technique that I term formal mixture. After tracing its origin to certain works See table of contents by J. S. Bach, C. P. E Bach, Domenico Scarlatti, and Joseph Haydn, I demonstrate how Beethoven built upon his predecessors’ use of the technique throughout his career, thereby expanding and diversifying the tonal resources of late classical era sonata forms. Publisher(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 1911-0146 (print) 1918-512X (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article MacKay, J. S. (2010). Formal Mixture in the Sonata-Form Movements of Middle- and Late-Period Beethoven. Intersections, 31(1), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.7202/1009287ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit des universités canadiennes, 2012 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit.