Gian Carlo Menotti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Reference No. Collection Site

PASSPORTS APPLIED IN PCG DUBAI/FSPsRCOsManila/VFS(PaRC) PASSPORTS READY FOR RELEASE AS OF 29 August 2021 RELEASING SECTION 8-12NN, 1-5PM, SUN-THU, EXCEPT HOLIDAYS TO SEARCH FOR YOUR NAME press "CONTROL F" OR "F3". If your name is already listed, please proceed to your designated Collection Site with your OLD PASSPORT AND OFFICIAL RECEIPT to claim your new e- passport. If the applicant cannot come personally to collect the passport, authorize someone to pick-up the passport. The following are the requirements: AUTHORIZATION LETTER, OLD PASSPORT, ORIGINAL RECEIPT, AND ORIGINAL AND COPY OF VALID IDENTIFICATION CARD OF AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE. WRITE THE REFERENCE NUMBER AT THE TOP OF YOUR RECEIPT UPON CLAIMING YOUR PASSPORT Middle Collection Last name First name Reference No. name Site AARTS ESRA MAE R. 2000106100360 DubaiPCG ABABA ROLANDO JR. I. 2000134000360 DubaiPCG ABACAN RENELYN D. 2000122300360 DubaiPCG ABAD MARIA EMMA D. 2000120550360 DubaiPCG ABAD CRISALDO B. 2000121900360 DubaiPCG ABAD ARIANNE FAYE D. 2000016765000 PaRC ABAD MICHELLE JANE D. 2000135890360 DubaiPCG ABAD MA. LAVINIA R. 2000037215000 PaRC ABAD SARAH T. 2000037435000 PaRC ABAD GERALD E. 2000137190360 Dubai PCG ABAD PAOLO NOEL R. 2000038495000 PaRC ABADILLA JOJO A. 2000017505000 PaRC ABAGAT LILIA D. 2000037825000 PaRC ABALAYAN AUDREIL O. 2000017855000 PaRC ABALAYAN MILDRED O. 2000017865000 PaRC ABALLE JESIE FE S. 2000136280360 Dubai PCG ABALOS ARRA BELLA J. 2000019735000 PaRC ABALOS BLENS RADIEL S. 2000136930360 Dubai PCG ABALOS LIZA C. 2000037855000 PaRC ABALOS ALDRIN D. 2000038055000 PaRC ABALUS XYNE AUBRIELLE C. 2000124910360 DubaiPCG ABANICO DANILO JR. M. 2000106680360 DubaiPCG ABAO DANIEL V. 2000120610360 DubaiPCG ABAO MARY LYN A. -

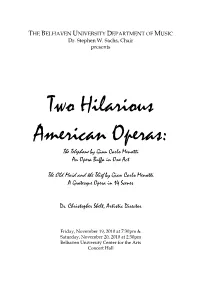

The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti a Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Two Hilarious American Operas: The Telephone by Gian Carlo Menotti An Opera Buffa in One Act The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti A Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes Dr. Christopher Shelt, Artistic Director Friday, November 19, 2010 at 7:30pm & Saturday, November 20, 2010 at 2:30pm Belhaven University Center for the Arts Concert Hall BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC MISSION STATEMENT The Music Department seeks to produce transformational leaders in the musical arts who will have profound influence in homes, churches, private studios, educational institutions, and on the concert stage. While developing the God-bestowed musical talents of music majors, minors, and elective students, we seek to provide an integrative understanding of the musical arts from a Christian world and life view in order to equip students to influence the world of ideas. The music major degree program is designed to prepare students for graduate study while equipping them for vocational roles in performance, church music, and education. The Belhaven University Music Department exists to multiply Christian leaders who demonstrate unquestionable excellence in the musical arts and apply timeless truths in every aspect of their artistic discipline. The Music Department would like to thank our many community partners for their support of Christian Arts Education at Belhaven University through their advertising in “Arts Ablaze 2010-2011” (should be published and available on or before September 30, 2010). Special thanks tonight to Bo-Kays Florist for our reception table flowers. It is through these and other wonderful relationships in the greater Jackson community that makes an afternoon like this possible at Belhaven. -

Samuel Barber (1910-1981)

Catalogue thématique des œuvres I. Musique orchestrale Année Œuvre Opus 1931 Ouverture « The School for Scandal » 5 1933 Music for a Scene from Shelley 7 1936 Symphonie in One Movement 9 Adagio pour orchestre à cordes [original : deuxième mouvement du 1938 11 Quatuor à cordes op.11, 1936] 1937 Essay for orchestra 12 1939 Concerto pour violon & orchestre 14 1942 Second Essay for Orchestra 17 1943 Commando March - 1944 Serenade pour orchestre à cordes [original pour quatuor à cordes, 1928] 1 1944 Symphonie n°2 19 1944 Capricorn Concerto pour flûte, hautbois, trompette & cordes 21 1945 Concerto pour violoncelle & orchestre 22 1945 Horizon, pour vents, timbales, harpe & orchestre à cordes - Medea (Serpent Heart) [version révisée Cave of the Heart, 1947 ; arr. Suite 1946 23 de ballet, 1947] 1952 Souvenirs [original : piano à quatre mains, 1951] 28 1953 Medea’s Meditation and Dance of Vengeance 23a 1960 Toccata Festiva pour orgue & orchestre 36 1960 Die Natali - Chorale Preludes for Christmas 37 1962 Concerto pour piano & orchestre 38 1964 Night Flight [arr. deuxième mouvement de la Symphonie n°2] 19a 1971 Fadograph of a Yestern Scene 44 1978 Third Essay for Orchestra 47 Canzonetta pour hautbois & orchestre à cordes [op. posth., complété 1978 48 et orchestré par Charles Turner] © 2009 Capricorn Association des amis de Samuel Barber II. Musique instrumentale Année Œuvre Opus 3 Sketches pour piano : Lovesong / To My Steinway n°220601 / 1923-24 - Minuet Fresh from West Chester (Some Jazzings) pour piano : Poison Ivy 1925-26 - / Let’s Sit it Out, I’d Rather Watch 1931 Interlude I (« Adagio for Jeanne ») pour piano - 1932 Interlude II pour piano - 1932 Suite for Carillon - 1942-44 Excursions pour piano 20 1949 Sonate pour piano 26 Souvenirs pour piano à quatre mains [arr. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Gian Carlo Di Renzo, MD, PhD Professional Address Gian Carlo Di Renzo Professor and Chairman Dept. of Ob/Gyn Director, Centre for Perinatal and Reproductive Medicine Santa Maria della Misericordia University Hospital 06132 San Sisto - Perugia - Italy tel. +39 075 5783829 tel. +39 075 5783231 fax +39 075 5783829 [email protected] Date of birth: 13 June 1951 Place of birth: Verona, Italy Citizenship: Italian 1 Director of Education and Communication & Past General Secretary of FIGO University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy. Prof. Gian Carlo Di Renzo is currently Professor and Chair at the University of Perugia (2004 - ), and Director of the Reproductive and Perinatal Medicine Center (1996 - ) , former Director of the Midwifery School (2004-2016), University of Perugia, in addition to being the Director of the Permanent International and European School of Perinatal and Reproductive Medicine (PREIS) in Florence (2012 - ) . After graduation cum laude at Medical School of the University of Padova (1975) , he was a research fellow at the Universities of Verona, Messina and Modena. After training at CHUV in Lausanne (Switzerland), at UCH in London (UK), at the University of Texas in Dallas (USA), and at the Catholic University in Nijmegen (NL) (1977-1982), he became a senior researcher at the University of Perugia. Since 2004 he is Professor and Chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University or Perugia., Chairman of the Midwifery School in the year 2004 to 2016, of the Ob Gyn Resident’s program since 2008 and of the PhD Program in Translational Medicine since 2012. He was general Secretary of the Italian Society of Perinatal Medicine, President of the Italian Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Secretary-Treasurer of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, President from 2000 to 2002, 2002-2008 Executive Director and Chairman of the Educational Committee, Vice President of the World Association of Perinatal Medicine ( 2007-2013) . -

BEYOND the BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100

BEYOND THE BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100 BEYOND THE BASICS – Contents Page 1 of 37 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................. 4 FOR FULL ORCHESTRA ................................................................. 5 Bernstein on Broadway ........................................................... 5 Bernstein and The Ballet ......................................................... 5 Bernstein and The American Opera ........................................ 5 Bernstein’s Jazz ....................................................................... 6 Borrow or Steal? ...................................................................... 6 Coolness in the Concert Hall ................................................... 7 First Symphonies ..................................................................... 7 Romeos & Juliets ..................................................................... 7 The Bernstein Beat .................................................................. 8 “Young Bernstein” (working title) ........................................... 9 The Choral Bernstein ............................................................... 9 Trouble in Tahiti, Paradise in New York .................................. 9 Young People’s Concerts ....................................................... 10 CABARET.................................................................................... 14 A’s and B’s and Broadway .................................................... -

Musical Influences Statistics

Composers Individuals’ Influence on Composer Composer’s Influence on Others Overall Name Sum+ Sum- n Mean1 Mean2 S. D. Sum- Sum+ n/n+ Sum Mean S. D. Rank Adam, Adolphe 0 0 4 1.90 0. .87 0 0 2/3 6.4 2.25 .35 277 Adams, John 0 9 13 3.07 -.69 1.54 - - - - - - 191 Adler, Samuel 0 0 6 2.58 0. .88 - - - - - - 312 Alain, Jehan 0 0 7 2.49 0. .98 - - - - - - 308 Albéniz, Isaac 3 6 11 3.39 -.27 1.30 0 0 8 19.9 2.49 .83 87 Albinoni, Tomaso 1 0 3 2.40 .33 .83 0 0 6 19.3 3.22 2.05 135 Alfvén, Hugo 0 2 8 3.36 -.25 1.35 - - - - - - 384 Alkan, (Charles-)Valentin 0 6 12 3.68 -.50 1.49 0 0 1 4.0 4.0 0. 317 Allegri, Gregorio 0 0 1 2.30 0. 0. 0 5 2 5.5 2.75 1.35 459 Alwyn, William 0 2 16 3.21 -.13 .79 - - - - - - 491 Amram, David 0 0 0 - - - - - - - - - 478 Anderson, Leroy 0 0 3 2.63 0. .66 - - - - - - 432 Andriessen, Louis 0 7 12 2.75 -.58 1.42 - - - - - - 360 Arensky, Anton 0 3 7 3.54 -.43 1.01 0 0 3 7.5 2.50 .73 323 Argento, Dominick 0 7 9 3.23 -.78 1.48 0 0 1 1.5 1.50 0. 296 Arne, Thomas 1 0 4 2.63 .25 1.20 - - - - - - 252 Arnold, Malcolm 0 2 10 2.83 -.20 .78 - - - - - - 155 Auber, Daniel-François-Esprit 2 0 5 3.12 .40 1.75 0 0 15 37.4 2.49 1.15 447 Auric, Georges 0 1 6 2.75 -.17 .71 0 0 1 1.4 1.40 0. -

Westchester Music Man Harold Rosenbaum Shares His Alphabetical Favorites

Subscribe Digital Edition Give a Gift Customer Service WestchesterBest Places To Live Today's Music News What To Do ManLocal Business Harold Guide Blogs Real Estate Top Doctors Top Dentists High School Chart Take Our Reader Survey Rosenbaum Shares His Alphabetical Favorites ® County people and places that strike a chord with renowned choral conductor Harold Rosenbaum. BY HAROLD ROSENBAUM; LLUSTRATION BY CAITLIN KUHWALD EAT & DRINK LIFE & STYLE ARTS & CULTURE INSIDER GUIDES BEST OF WESTCHESTER® Facebook Twitter Google+ Pinterest Ancient houses. Not by European RELATED STORIES standards, but who cares? Barber in Cross River, who also replaces watchbands. It reminds me of the Wild West, where barbers also extracted teeth! Copland House in Cortlandt Manor. Yes, Aaron actually lived there. I conducted his choral Urban Planning Pioneer Seeks To Upgrade masterpiece In the Beginning at his 80th birthday Playland celebration at Symphony Space in NYC. Dirt roads. Sure, they can be a muddy mess when it rains, but they are a nice reminder of our past. Edie, my amazing, talented, beautiful, kind wife, who, among many other things, runs our youth choir, The Canticum Novum Singers. How Baseball Sparked Doris Kearns Goodwin's Love Of History Farms. Real ones. One can join some of them to obtain organic produce weekly. Grandsons. My three—who force me to be normal at times (well, at least goofy and regressive). Horse & Hound Inn, which accommodates my diet every time (I haven’t had meat, fish, dairy, or grains for decades). Idealists. There are plenty of them here, with solar panels, food-producing farm animals, and world-class gardens. -

Distribution Agreement in Presenting This Thesis As A

Distribution Agreement In presenting this thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree from Emory University, I hereby grant to Emory University and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive, make accessible, and display my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter now, including display on the World Wide Web. I understand that I may select some access restrictions as part of the online submission of this thesis. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis. Naomi P. Newton April 12, 2016 Storytelling In Opera, Operetta, and American Musical Theater A Research-Performance Honors Thesis by Naomi P. Newton Kristin Wendland, PhD Adviser Bradley Howard, MM Adviser Department of Music Kristin Wendland, PhD Adviser Bradley Howard, MM Adviser Stephen Crist, PhD Committee Member Arri Eisen, PhD Committee Member 2016 Storytelling In Opera, Operetta, and American Musical Theater A Research-Performance Honors Thesis By Naomi P. Newton Kristin Wendland, PhD Adviser Bradley Howard, MM Adviser Department of Music An abstract of a thesis submitted to the Faculty of Emory College of Arts and Sciences of Emory University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors. Department of Music 2016 Abstract Storytelling In Opera, Operetta, and American Musical Theater A Research-Performance Honors Thesis By Naomi P. Newton This thesis represents one aspect of my dual research-performance honors project. -

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014

SOME AMERICAN OPERAS/COMPOSERS October 2014 Mark Adamo-- Little Women, Lysistrata John Adams—Nixon in China, Death of Klinghoffer, Doctor Atomic Dominick Argento—Postcard From Morocco, The Aspern Papers William Balcom—A View From the Bridge, McTeague Samuel Barber—Antony and Cleopatra, Vanessa Leonard Bernstein— A Quiet Place, Trouble in Tahiti Mark Blitzstein—Regina, Sacco and Venzetti, The Cradle Will Rock David Carlson—Anna Karenina Aaron Copland—The Tender Land John Corigliano—The Ghosts of Versailles Walter Damrosch—Cyrano, The Scarlet Letter Carlisle Floyd—Susannah, Of Mice and Men, Willie Stark, Cold Sassy Tree Lukas Foss—Introductions and Goodbyes George Gershwin—Porgy and Bess Philip Glass—Satyagraha, The Voyage, Einstein on the Beach, Akhnaten Ricky Ian Gordon—Grapes of Wrath Louis Gruenberg—The Emperor Jones Howard Hanson—Merry Mount John Harbison—The Great Gatsby, Winter’s Tale Jake Heggie—Moby Dick, Dead Man Walking Bernard Hermann—Wuthering Heights Jennifer Higdon—Cold Mountain (World Premiere, Santa Fe Opera, 2015) Scott Joplin—Treemonisha Gian Carlo Menotti—The Consul, The Telephone, Amahl and the Night Visitors Douglas Moore—Ballad of Baby Doe, The Devil and Daniel Webster, Carrie Nation Stephen Paulus—The Postman Always Rings Twice, The Woodlanders Tobias Picker—An American Tragedy, Emmeline, Therese Racquin Andre Previn—A Streetcar Named Desire Ned Rorem—Our Town Deems Taylor—Peter Ibbetson Terry Teachout—The Letter Virgil Thompson—Four Saints in Three Acts, The Mother of Us All Stewart Wallace—Harvey Milk Kurt Weill—Street Scene, Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny . -

Program Notes | Amahl and the Night Visitors

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, December 13, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, December 15, at 8:00 Bramwell Tovey Conductor and Narrator Dante Michael DiMaio Boy Soprano (Amahl) Renée Tatum Mezzo-soprano (His Mother) Andrew Stenson Tenor (King Kaspar) Brandon Cedel Bass-baritone (King Melchior) David Leigh Bass (King Balthazar) Kirby Traylor Bass (The Page) Philadelphia Symphonic Choir (Shepherds and Villagers) Amanda Quist Director Omer Ben Seadia Stage Director Walton Crown Imperial (Coronation March) Britten The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34 Intermission Menotti Amahl and the Night Visitors First complete Philadelphia Orchestra performances Ryan Howell, designer Chris Frey, lighting desig This program runs approximately 1 hour, 45 minutes. These concerts are part of the Fred J. Cooper Memorial Organ Experience, supported through a generous grant from the Wyncote Foundation. The December 15 concert is sponsored by Medcomp. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. PO Book 16_Home.indd 23 12/7/18 10:35 AM 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage.