Georgia's New Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Georgia — Municipal Elections, 30 May 2010

INTERNATIONAL ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION Georgia — Municipal Elections, 30 May 2010 STATEMENT OF PRELIMINARY FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS PRELIMINARY CONCLUSIONS The 30 May municipal elections marked evident progress towards meeting OSCE and Council of Europe commitments. However, significant remaining shortcomings include deficiencies in the legal framework, its implementation, an uneven playing field, and isolated cases of election-day fraud. The authorities and the election administration made clear efforts to pro-actively address problems. Nevertheless, the low level of public confidence persisted. Further efforts in resolutely tackling recurring misconduct are required in order to consolidate the progress and enhance public trust before the next national elections. While the elections were overall well administered, systemic irregularities on election day were noted, as in past elections, in particular in Kakheti, Samtskhe-Javakheti and Shida Kartli. The election administration managed these elections in a professional, transparent and inclusive manner. The new Central Election Commission (CEC) chairperson tried to reach consensus among CEC members, including those nominated by political parties, on all issues. For the first time, Precinct Election Commission (PEC) secretaries were elected by opposition-appointed PEC members, which was welcomed by opposition parties and increased inclusiveness. The transparency of the electoral process was enhanced by a large number of domestic observers. Considerable efforts were made to improve the quality of voters’ lists. In the run-up to these elections, parties received state funding to audit the lists. Voters were given sufficient time and information to check their entries. As part of the recent UEC amendments, some restrictions were placed on the rights of certain categories of citizens to vote in municipal elections, in order to address opposition parties’ concerns of possible electoral malpractices. -

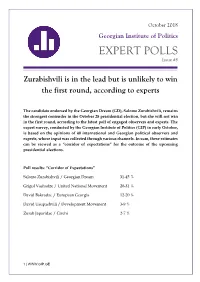

EXPERT POLLS Issue #8

October 2018 Georgian Institute of Politics EXPERT POLLS Issue #8 Zurabishvili is in the lead but is unlikely to win the first round, according to experts The candidate endorsed by the Georgian Dream (GD), Salome Zurabishvili, remains the strongest contender in the October 28 presidential election, but she will not win in the first round, according to the latest poll of engaged observers and experts. The expert survey, conducted by the Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) in early October, is based on the opinions of 40 international and Georgian political observers and experts, whose input was collected through various channels. In sum, these estimates can be viewed as a “corridor of expectations” for the outcome of the upcoming presidential elections. Poll results: “Corridor of Expectations” Salome Zurabishvili / Georgian Dream 31-45 % Grigol Vashadze / United National Movement 20-31 % David Bakradze / European Georgia 12-20 % David Usupashvili / Development Movement 3-9 % Zurab Japaridze / Girchi 2-7 % 1 | WWW.GIP.GE Figure 1: Corridor of expectations (in percent) Who is going to win the presidential election? According to surveyed experts (figure 1), Salome Zurabishvili, who is endorsed by the governing Georgian Dream party, is poised to receive the most votes in the upcoming presidential elections. It is likely, however, that she will not receive enough votes to win the elections in the first round. According to the survey, Zurabishvili’s vote share in the first round of the elections will be between 31-45%. She will be followed by the United National Movement (UNM) candidate, Grigol Vashadze, who is expected to receive between 20-31% of votes. -

Misuse of Administrative Resources During Georgia's 2020

Misuse of Administrative Resources during Georgia’s 2020 Parliamentary Elections Final Report December 2020 Authors Gigi Chikhladze Tamta Kakhidze Co-author and research supervisor Levan Natroshvili This report was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The opinions expressed in the report belong to Transparency International Georgia and may not reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents Key Findings ____________________________________________________________________ 4 Introduction ____________________________________________________________________ 7 Chapter I. What is the misuse of administrative resources during electoral processes? ____________________________________________________________________ 8 Chapter II. Misuse of Enforcement Administrative Resources during Electoral Processes ____________________________________________________________________ 9 1. Violence, threatening, intimidation, and law enforcement response _________ 10 1.1. Incidents that occurred during the pre-election period _____________________ 10 1.2. Incidents that occurred during the Election Day ____________________________ 14 1.3. Incidents that occurred after the Election Day ____________________________ 15 2. Destruction of political party property and campaigning materials and law enforcement response to them _________________________________________________ 15 3. Use of water cannons against demonstrators gathered at the CEC ___________ 16 4. -

Letter of Concern of April 2015

7 April 2015 Mr Giorgi Margvelashvili President of Georgia Abdushelishvili st. 1, Tbilisi, Georgia1 Mr Irakli Garibashvili Prime Minister of Georgia 7 Ingorokva St, Tbilisi 0114, Georgia2 Mr David Usupashvili Chairperson of the Parliament of Georgia 26, Abashidze Street, Kutaisi, 4600 Georgia Email: [email protected] Political leaders in Georgia must stop slandering human rights NGOs Mr President, Mr Prime Minister, Mr Chairperson, We, the undersigned members and partners of the Human Rights House Network and the South Caucasus Network of Human Rights Defenders, call upon political leaders in Georgia to stop slandering non-governmental organisations with unfounded accusations and suggestions that their work would harm the country. Since October 2013, public verbal attacks against human rights organisations by leading political figures in Georgia have increased. The situation is starting to resemble to an anti-civil society campaign. In October 2013, the Vice Prime Minister and Minister for Energy Resources of Georgia, Kakhi Kaladze, criticised the non-governmental organisations, which opposed the construction of a hydroelectric power plant and used derogatory terms to express his discontent over their protest.3 In May 2014, you, Mr Prime Minister, slammed NGOs participating in the campaign about privacy rights, “This Affects You,”4 and stated that they “undermine” the functioning of the State and “damage of the international reputation of the country.”5 Such terms do not value disagreement with NGOs and their participation in public debate, but rather delegitimised their work. Further more, the Prime Minister’s statement encouraged other politicians to make critical statements about CSOs and start activities against them. -

Monitoring the Implementation of the Code of Conduct by Political Parties in Georgia

REPORT MONITORING THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CODE OF CONDUCT BY POLITICAL PARTIES IN GEORGIA PREPARED BY GEORGIAN INSTITUTE OF POLITICS - GIP MAY 2021 ABOUT The Georgian Institute of Politics (GIP) is a Tbilisi-based non-profit, non-partisan, research and analysis organization. GIP works to strengthen the organizational backbone of democratic institutions and promote good governance and development through policy research and advocacy in Georgia. It also encourages public participation in civil society- building and developing democratic processes. The organization aims to become a major center for scholarship and policy innovation for the country of Georgia and the wider Black sea region. To that end, GIP is working to distinguish itself through relevant, incisive research; extensive public outreach; and a bold spirit of innovation in policy discourse and political conversation. This Document has been produced with the financial assistance of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the GIP and can under no circumstance be regarded as reflecting the position of the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. © Georgian Institute of Politics, 2021 13 Aleksandr Pushkin St, 0107 Tbilisi, Georgia Tel: +995 599 99 02 12 Email: [email protected] For more information, please visit www.gip.ge Photo by mostafa meraji on Unsplash TABLE OF CONTENTS 4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 KEY FINDINGS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 METHODOLOGY 11 POLITICAL CONTEXT OF 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS AND PRE-ELECTION ENVIRONMENT -

Technical Election Assessment Mission: Georgia 2020 Parliamentary Election Interim Report

TECHNICAL ELECTION ASSESSMENT MISSION: GEORGIA 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION INTERIM REPORT TECHNICAL ELECTION ASSESSMENT MISSION: GEORGIA 2020 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTION INTERIM REPORT International Republican Institute IRI.org @IRI_Polls © 2020 All Rights Reserved Technical Election Assessment Mission: Georgia 2020 Parliamentary Election Interim Report Copyright © 2020 International Republican Institute. All rights reserved. Permission Statement: No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without the written permission of the International Republican Institute. Requests for permission should include the following information: • The title of the document for which permission to copy material is desired. • A description of the material for which permission to copy is desired. • The purpose for which the copied material will be used and the manner in which it will be used. • Your name, title, company or organization name, telephone number, fax number, e-mail address and mailing address. Please send all requests for permission to: Attn: Department of External Affairs International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005 [email protected] IRI | Technical Electoral Assessment Mission: Georgia 2020 Parliamentary Election Interim Report 3 INTRODUCTION In June and July of 2020, the government of Georgia adopted significant constitutional and election reforms, including a modification of Georgia’s mixed electoral system and a reduction in the national proportional threshold from 5 percent to 1 percent of vote share — presenting an opportunity for citizens to pursue viable third-party options and the possibility of a new coalition government after decades of single-party domination. -

Elections in Georgia 2014 Local Self-Government Elections

Elections in Georgia 2014 Local Self-Government Elections Frequently Asked Questions Europe and Asia International Foundation for Electoral Systems 1850 K Street, NW | Fifth Floor | Washington, D.C. 20006 | www.IFES.org June 9, 2014 Frequently Asked Questions Who will Georgians elect on June 15, 2014? ................................................................................................ 1 Why are the local self-government elections important? What is at stake? ............................................... 1 What are the changes to the local self-government elections in 2014? ...................................................... 2 Will there be any changes in the way voters are identified on the voter lists on Election Day? ................. 3 What is the current political situation in Georgia? ....................................................................................... 3 What is the state of political parties in Georgia? ......................................................................................... 4 When will the results be announced? .......................................................................................................... 4 What laws regulate the self-government elections in Georgia? .................................................................. 4 Who is eligible to run for mayor, gamgebeli, or sakrebulo member? .......................................................... 5 What political parties are registered for the 2014 local self-government elections? ................................. -

David Usupashvili

David Usupashvili Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia David Usupashvili was elected as Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia on October 21, 2012. He has been Chairman of the Republican Party of Georgia (ALDE and LI member party) since 2005 and Deputy Chairman of the Political Coalition “Georgian Dream” since October 2011. David Usupashvili was born in Signagi, Georgia, on March 5, 1968. He graduated from Magaro Secondary School and continued education at IvaneJavakhishvili Tbilisi State University, where he obtained Diploma of Honours in Law (1985 - 1992). He received Master’s Degree in International Development Policy from Duke University, Terry Sanford Institute of Public Policy, USA (1997 - 1999). From 1999 to 2005 he worked for an USAID funded Rule of Law program, as Deputy Chief of Party and Senior Legal and Policy Advisor. During 2000 – 2001,David Usupashvili worked as an Executive Secretary for Anti-Corruption Working Group under President of Georgia. David Usupashvili was a founder of one of the first Georgian NGOs, Georgian Young Lawyers Associationthat promoted and largely contributed to democratization processes in Georgia. As a first Chairman he coordinated implementation of major rule of law programs (1994 - 1997). From 1992 to 1994 he worked for the President of Georgia as Senior Legal Adviser and Special Envoy of the President to Parliament and Constitutional Commission of Georgia. From 1989 to 1995 he served at the Central Election Commission of Georgia, as Chief Legal Consultant, Head of Legal Department and Member. David Usupashvili was a member of various boards of the leading Georgian NGOs such as GYLA, OSGF, TI, ISFED, ect. -

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Georgia May 20 – June 11, 2019 Detailed Methodology • The field work was carried out by Institute of Polling & Marketing. The survey was conducted by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene of the public and market research company Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the International Republican Institute’s Center for Insights in Survey Research. • Data was collected throughout Georgia between May 20 and June 11, 2019, through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ home. • The sample consisted of 1,500 permanent residents of Georgia aged 18 or older and eligible to vote. It is representative of the general population by age, gender, region and size of the settlement. • A multistage probability sampling method was used with random route and next-birthday respondent selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Georgia are grouped into 10 regions. All regions of Georgia were surveyed (Tbilisi city – as separate region). • Stage two: Selection of the settlements – cities and villages. • Settlements were selected at random. The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in each region. • Stage three: Primary sampling units were described. • The margin of error does not exceed plus, or minus 2.5 percent and the response rate was 68 percent. • The achieved sample is weighted for regions, gender, age, and urbanity. • Charts and graphs may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding. • The survey was funded by the -

![Download [Pdf]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1586/download-pdf-2311586.webp)

Download [Pdf]

This project is co-funded by the Seventh Framework Programme for Research and Technological Development of the European Union EU Grant Agreement number: 290529 Project acronym: ANTICORRP Project title: Anti-Corruption Policies Revisited Work Package: WP3, Corruption and governance improvement in global and continental perspectives Title of deliverable: D3.2.7. Background paper on Georgia Due date of deliverable: 28 February 2014 Actual submission date: 28 February 2014 Author: Andrew Wilson Editor: Alina Mungiu-Pippidi Organization name of lead beneficiary for this deliverable: Hertie School of Governance Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Seventh Framework Programme Dissemination Level PU Public X PP Restricted to other programme participants (including the Commission Services) RE Restricted to a group specified by the consortium (including the Commission Services) Co Confidential, only for members of the consortium (including the Commission Services) Georgia Background Report Andrew Wilson University College London January 2014 ABSTRACT Georgia had a terrible reputation for corruption, both in Soviet times and under the presidency of Eduard Shevardnadze (1992-2003). After the ‘Rose Revolution’ that led to Shevardnadze’s early resignation, many proclaimed that the government of new President Mikheil Saakashvili was a success story because of its apparent rapid progress in fighting corruption and promoting neo-liberal market reforms. His critics, however, saw only a façade of reform and a heavy hand in other areas, even before the war with Russia in 2008. Saakashvili’s second term (2008-13) was much more controversial – his supporters saw continued reform under difficult circumstances, his opponents only the consolidation of power. Under Saakashvili Georgia does indeed deserve credit for its innovative reforms that were highly successful in reducing ‘low-level’ corruption. -

To: Mr. Giorgi Margvelashvili, President of Georgia Mr. Irakli Garibashvili, Prime Minister of Georgia Mr

To: Mr. Giorgi Margvelashvili, President of Georgia Mr. Irakli Garibashvili, Prime Minister of Georgia Mr. David Usupashvili , Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia Your Excellency Mr. President, Mr. Prime-Minister, Mr. Chairman of the Parliament, As you are aware, the Constitutional Court of Georgia is the highest judicial body of the constitutional review. Thus, the reputation of its judges, their impartiality as well as the insurance of their independent activity are the key factors of building the confidence towards the court and the precondition of its effective functioning. Let me inform you that last period unlawful conducts have taken place against the Constitutional Court of Georgia and its members, jeopardizing the Court's independent, uninterrupted activity. Such unlawful activities have recently acquired even more organized, coordinated and permanent character. On 11 April 2014, a rally was held in front of the Constitutional Court, whilst the demonstrators made threatening statements related to the activity of the Court. The demonstrators, by using threats, were demanding the Court to make a preferred judgment1 during which the property of the Court was damaged. The incident was condemned by the representatives of the civil society2. However, the law enforcement authorities did not respond in any way. We are also concerned about the statements regarding threats of revenge made on 6 April 2015 towards the President of the Constitutional Court and his family members in front of the Constitutional Court of Georgia3 building by the participants of the assemblage. In connection with the aforementioned, on 7 April 2015 the Constitutional Court made a written appeal to the Chief Prosecutor of Georgia, Mr. -

Change of Government in Georgia. New Emphases in Domestic And

Introduction Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik ments German Institute for International and Security Affairs m Co Change of Government in Georgia WP New Emphases in Domestic and Foreign Policy Sabine Fischer and Uwe Halbach S In autumn 2012, Georgia underwent a development that is already being described as historical. Following an emotional and at times hostile election contest, the Georgian parliamentary elections on 1 October led to a change of government, which the country is hailing as proof of its democratic maturity. President Mikheil Saakashvili’s United National Movement party, which had been in power for the last nine years and held a two-thirds majority in the last parliament, suffered a clear defeat against a coalition of six opposition parties, none of whom had been represented in the previous parliament. Saakashvili will remain in office until 2013. What course will the new coalition govern- ment under Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili now set in domestic and foreign policy? Will the incumbent president, who is endowed with a wide range of powers, and the new government be able to work together in the run-up to the 2013 presidential elec- tions or will they become entrenched in bitter rivalry? If the opposing political camps led by change that has not been brought about by President Saakashvili and Prime Minister a coup d’etat. Ivanishvili succeed in working together Before the elections, voices warning of a peacefully up until the presidential elec- polarisation of society were getting louder tions (due to be held in October 2013), this both in Georgia and abroad. The country’s change of government could justifiably be highest moral authority, the head of the considered exceptional.