Radical Documentaries, Neoliberal Crisis and Post-Democ- Racy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19 Mapping the Citizen News Landscape: Blurring Boundaries, Promises, Perils, and Beyond

An Nguyen and Salvatore Scifo 19 Mapping the Citizen News Landscape: Blurring Boundaries, Promises, Perils, and Beyond Abstract: This chapter offers a necessary critical overview of citizen journalism in its many forms and shapes, with a focus on its promises and perils and what it means for the future of news. We will start with a review of the concept of “citizen journalism” and its many alternative terms, then move to briefly note the long history of citizen journalism, which dates back to the early days of the printing press. This will be followed by our typology of three major forms of citizen journal- ism (CJ) – citizen witnessing, oppositional CJ, and expertise-based CJ – along with an assessment of each form’s primary actions, motives, functions, and influences. The penultimate part of the chapter will focus on CJ’s flaws and pitfalls – especially the mis/disinformation environment it fosters and the “dialogue of the deaf” it engenders – and place them in the context of the post-truth era to highlight the still critical need for professional journalists. The chapter concludes with a brief review of the understandably but unnecessarily uneasy relationship between citi- zen and professional journalism and calls for the latter to adopt a new attitude to work well with the former. Keywords: citizen journalism, alternative journalism, citizen witnessing, social media, fake news, post-truth 1 One thing, many labels? Within a short time, citizen journalism (CJ) went from something of a novelty to a naturalized part of the news ecosystem and entered the daily language of journal- ists, journalism educators, and a large segment of the global public. -

Selections from the State Librarian with Comments Fall 2003 Through Summer 2008

Selections from the State Librarian With comments Fall 2003 through Summer 2008 Each season for the past five years Jan Walsh, Washington State Librarian, has chosen a theme and then selected at least one adult, one young adult, and one children‟s book to fit her topic. The following list is a compilation of her choices with her comments. The season in which each title was selected is listed in parentheses following its citation. Her themes were: Artists of Washington—spring 2004 Beach Reads—summer 2008 The Columbia River through Washington History—fall 2004 Courage—summer 2005 Disasters—fall 2007 Diversity—winter 2006 Exploring Washington—spring 2008 Geology of Washington State—fall 2005 Hidden People—spring 2007 Lewis, Clark, and Seaman—winter 2004 Life in Washington Territory—fall 2003 Mount St. Helens—spring 2005 Mysteries of Washington—fall 2006 Of Beaches and the Sea—winter 2008 The Olympic Peninsula—winter 2007 The Oregon Trail—spring 2006 Spokane and the Inland Empire—summer 2007 Tastes of Washington—summer 2006 Washington through the Photographer‟s Lens—summer 2004 Washington‟s Native People—winter 2005 NW prefixed books are available for check out and interlibrary loan. RARE, R (Reference), and GWA (Governor‟s Writers Award) prefixed books are available to be viewed only at the State Library. All books were in print at the time of Ms. Walsh‟s selection. January 23, 2009 1 Washington Reads 5 year compilation with Jan‟s comments Adult selections Alexie, Sherman. Reservation Blues. Grove Press, 1995. 306 p. (Summer 2007) NW 813.54 ALEXIE 1995; R 813.54 ALEXIE 1995 “The novel, which won the American Book Award in 1996, is a poignant look at the rise and fall of an Indian rock band, Coyote Springs, and the people and spirits that surround it. -

The Bibliography of the Publications by Classmates in the Yale Class Of

The Bibliography of the Publications by Classmates in the Yale Class of 1956: Includes Work by Wives of Classmates, Work in the Book Exhibit of the 50th Reunion and Listings in the ABEbook Exchange as of 02-09-2018. Introduction Here is a list of 476 publications by 95 Classmates and 10 of their wives, which is probably the first of its kind of any Yale College Class, and, if not, should compare well with any other in scope. But then again, this compilation of so many by so few might symbolize the autumn of book-binding’s age that stretched from Gutenberg’s invention till today and might suggest that publications, free of paper words and numbers, be in bytes to digitally whisk the world-wide-web. Will this new era mark the waning of the printing press as it had once replaced bespoken Latin scripts? Will knowledge be transmitted more efficiently both to and from a heaping, horizontal cloud? NB: Publication data obtained directly from authors has been verified; the data from the Exchange has not been verified. Compiled by W. H. H. Rees Index: Adebonojo, Festus O., Page 3 Helmstadter, Richard J., Page13 Tuggle, Joyce, Page 27 Alegi, Peter C., Page 3 Hodge, Paul W., Page 13 Tunney, John Varick, Page 28 Ambach, Gordon M., Page 3 Huber, Paul B., Page 14 Tveskov, Peter H., Page 28 Anderson, Jeremy H., Page 3 Hutt, Peter Barton, Page 14 Vare, Edwin C., Page 28 Andersson, Theodore M., Page 3 Jaffe, Sheldon M., Page 14 Velsey, Donald W., Page 28 Baker, F. -

Five Year Compilation 2003-07

Selections from the State Librarian Fall 2003 through Summer 2008 Each season for the past five years Jan Walsh, Washington State Librarian, has chosen a theme and then selected at least one adult, one young adult and one children’s book to fit her topic. The following list is a compilation of her choices. The season in which each title was selected is listed in parentheses following its citation. Her themes were: Artists of Washington—spring 2004 Beach Reads—summer 2008 The Columbia River through Washington History—fall 2004 Courage—summer 2005 Disasters—fall 2007 Diversity—winter 2006 Exploring Washington—spring 2008 Geology of Washington State—fall 2005 Hidden People—spring 2007 Lewis, Clark, and Seaman—winter 2004 Life in Washington Territory—fall 2003 Mount St. Helens—spring 2005 Mysteries of Washington—fall 2006 Of Beaches and the Sea—winter 2008 The Olympic Peninsula—winter 2007 The Oregon Trail—spring 2006 Spokane and the Inland Empire—summer 2007 Tastes of Washington—summer 2006 Washington through the Photographer’s Lens—summer 2004 Washington’s Native People—winter 2005 To read Ms. Walsh’s comments about each book go to: http://www.secstate.wa.gov/library/wa_reads.aspx NW prefixed books are available for check out and interlibrary loan. RARE, R (Reference), and GWA (Governor’s Writers Award) prefixed books are available to be viewed only at the State Library. All books were in print at the time of Ms. Walsh’s selection. Five Year Compilation November 2008 1 Adult selections Alexie, Sherman. Reservation Blues. Grove Press, 1995. 306 p. (Summer 2007) NW 813.54 ALEXIE 1995; R 813.54 ALEXIE 1995 Alt, David D. -

18416.Brochure Reprint

RANDOMRANDOM HOUSEHOUSE PremiumPremium SalesSales && CustomCustom PublishingPublishing Build Your Next Promotion with THE Powerhouse in Publishing . Random House nside you’ll discover a family of books unlike any other publisher. Of course, it helps to be the largest consumer book publisher in the world, but we wouldn’t be successful in coming up with creative premium book offers if we didn’t have Ipeople who understand what marketers need. Drop in and together we’ll design your blueprint for success. Health & Well-Being You’re in good hands with a medical staff that includes the American Heart Association, American Medical Association, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Cancer Society, Dr. Andrew Weil and Deepak Chopra. Millions of consumers have received our health books through programs sponsored by pharmaceutical, health insurance and food companies. Travel Targeting the consumer or business traveler in a future promotion? Want the #1 brand name in travel information? Then Fodor’s, with its ever-expanding database to destina- tions worldwide, is the place to be. Talk to us about how to use Fodor’s books for your next convention or meeting and even about cross-marketing opportunities and state-of- the-art custom websites. If you need beauti- fully illustrated travel books, we also publish the Knopf Guides, Photographic Journey and other picture book titles. Call 1.800.800.3246 Visit us on the Web at www.randomhouse.com 2 Cooking & Lifestyle Imagine a party with Julia Child, Martha Stewart, Jean-Georges, and Wolfgang Puck catering the affair. In our house, we have these and many more award winning chefs and designers to handle all the details of good living. -

Random House, Inc. Booth #52 & 53 M O C

RANDOM HOUSE, INC. BOOTHS # 52 & 53 www.commonreads.com One family’s extraordinary A remarkable biography of The amazing story of the first One name and two fates From master storyteller Erik Larson, courage and survival the writer Montaigne, and his “immortal” human cells —an inspiring story of a vivid portrait of Berlin during the in the face of repression. relevance today. grown in culture. tragedy and hope. first years of Hitler’s reign. Random House, Inc. is proud to exhibit at this year’s Annual Conference on The First-Year Experience® “One of the most intriguing An inspiring book that brings novels you’ll likely read.” together two dissimilar lives. Please visit Booths #52 & 53 to browse our —Library Journal wide variety of fiction and non-fiction on topics ranging from an appreciation of diversity to an exploration of personal values to an examination of life’s issues and current events. With so many unique and varied Random House, Inc. Booth #52 & 53 & #52 Booth Inc. House, Random titles available, you will be sure to find the right title for your program! A sweeping portrait of Anita Hill’s new book on gender, contemporary Africa evoking a race, and the importance of home. world where adults fear children. “ . [A] powerful journalistic window “ . [A]n elegant and powerful A graphic non-fiction account of “ . [A] blockbuster groundbreaking A novel set during one of the most into the obstacles faced by many.” plea for introversion.” a family’s survival and escape heartbreaking symphony of a novel.” conflicted and volatile times in –MacArthur Foundation citation —Brian R. -

The Anatomy of a Moral Panic: Western Mainstream Media's

Changing Societies & Personalities, 2019 Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 189–206 http://dx.doi.org/10.15826/csp.2019.3.3.071 ARTICLE The Anatomy of a Moral Panic: Western Mainstream Media’s Russia Scapegoat Greg Simons Uppsala University, Sweden Turiba University, Latvia Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, Russia ABSTRACT Since 2014, there has been a very concerted campaign launched by the neo-liberal Western mainstream mass media against Russia. The format and content suggest that this is an attempt to induce a moral panic among the Western publics. It seems to be intended to create a sense of fear and to switch the logic to a series of emotionally- based reactions to assertion propaganda. Russia has been variously blamed for many different events and trends around the world, such as the “destroying” of Western “democracy”, and democratic values. In many regards, Russia is projected as being an existential threat in both the physical and intangible realms. This paper traces the strategic messages and narratives of the “Russia threat” as it is presented in Western mainstream media. Russia is connoted as a scapegoat for the failings of the neo-liberal democratic political order to maintain its global hegemony; therefore, Russia is viewed as the “menacing” other and a desperate measure to halt this gradual decline and loss of power and influence. This ultimately means that this type of journalism fails in its supposed fourth estate role, by directly aiding the hegemonic political power. KEYWORDS moral panic, Western mainstream media, Russia, propaganda, scapegoating, fourth estate Received 28 July 2019 © 2019 Gregory Simons Accepted 13 September 2019 [email protected] Published online 5 October 2019 190 Greg Simons Introduction Moral panic has been developed as a concept within sociology and came to greater attention after Stanley Cohen’s 1972 book on Folk Devils and Moral Panic. -

ENGL - 057 - 202040 Summer 2020

ENGL - 057 - 202040 Summer 2020 C 2019-20 Form 335 Update Form 335 Update Effective Term:* 202040 Summer 2020 Department:* English Department Discipline:* Developmental Writing Subject Code:* ENGL Course Number:* 057 Shortened Course Critical Connections: Rdg/Wrtg Title: Official Course Critical Connections in Reading and Writing Title:* Areas Updated:* Learning Outcomes Sequence of Instruction Textbooks/Required Materials Blended F2F Ratio Course Assessment Methods Maximum Enrollments Justification for Proposal:* Texts are updated routinely to ensure relevance and diversity Digital Description Credit Hours: 3 Lecture Hours: 3 Laboratory Hours: 0 Lecture Pay Hours: 3 / Lab Pay Hours: 0 Catalog Description/ Prerequisite/ Co- Focuses on the two areas of reading and writing. This course is designed to help the requisites: student develop and use the strategies and skills needed to negotiate and understand readings, and to compose text. A grade of C or higher in this course completes the developmental sequences in both reading (ENGL 003) and writing (ENGL 051) required for enrollment into any other courses that require ENGL 003 and/or ENGL 051 as prerequisites. Prerequisite: ENGL 003 entry-level performance in the College Testing and Placement Program, or ENGL 002 with a grade of C or higher, and ENGL 051 placement, or completion of ENGL 050 with a grade of C or higher. Learning Outcomes: The integrated Reading and Writing curriculum as designed is rooted in the belief that there is significant interplay between reading and writing and the ways the two disciplines work together to develop students’ literacy. Therefore, the outcomes focus on the interplay between the two areas – reading and writing – while acknowledging that students require intentional practice in becoming active critical readers who possess the ability to respond critically to text and at the same time in learning how to develop the conventions and practices of academic writing. -

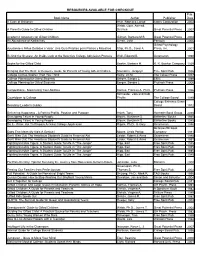

RESOURCES AVAILABLE for CHECKOUT Pub

RESOURCES AVAILABLE FOR CHECKOUT Pub. Book Name Author Publisher Date A Case of Brilliance Hein, Rebecca Lange Xlibris Corporation 2002 Webb, Gore, Amend, A Parent's Guide to Gifted Children DeVries Great Potential Press 2007 Academic Advocacy for Gifted Children Gilman, Barbara M.S. Great Potential Press 2008 An Abundance of Katherines Green, John Penguin 2006 Gifted Psychology Ayudando a Niños Dotados a Volar: Una Guia Práctica para Padres y Maestros Strip, Ph.D., Carol A. Press, Inc. 2001 Behind the Scenes: An Inside Look at the Selective College Admission Process Wall, Edward B. Octameron 1990 Books for the Gifted Child Baskin, Barbara H. R. R. Bowker Company 1929 Bringing Out The Best: A Resource Guide for Parents of Young Gifted Children Saunders, Jacqulyn Free Spirit Pub. 1986 College Comes Sooner Than You Think Reilly, Jill M. The Career Press 1987 College Planning for Gifted Students Berger, Sandra L. ERIC 1989 College Planning for Gifted Students Berger, Sandra L. Prufrock Press 2006 Competitions - Maximizing Your Abilities Karnes, Frances A. Ph.D. Prufrock Press 1996 Schneider, Zola and Kalb, Countdown to College Phyllis The College Board 1989 College Entrance Exam Deciding (Leader's Guide) Board 1972 Delivering Happiness - A Path to Profits, Passion and Purpose Hsieh, Tony Hachette Book Group 2010 Developing Talent in Young People Bloom, Benjamin S. Ballantine Books 1985 Developing Talent in Young People Bloom, Benjamin S. Ballantine Books 1985 Do It - Write: Hot To Prepare A Great College Application Ripple, Ph.D., G Gary Octameron 1986 McGraw-Hill Book Does This Mean My Kid's A Genius? Moore, Linda Perigo Company 1981 Don't Miss Out: The Ambitious Student's Guide to Financial Aid Leider, Robert & Anna Octameron 1988 Don't Miss Out: The Ambitious Student's Guide to Financial Aid Leider, Robert & Anna Octameron 1991 Fighting Invisible Tigers: A Student Guide To Life in "The Jungle" Hipp, Earl Free Spirit Pub. -

A Holmes and Doyle Bibliography

A Holmes and Doyle Bibliography Volume 2 Monographs and Serials By Subject Compiled by Timothy J. Johnson Minneapolis High Coffee Press 2010 A Holmes & Doyle Bibliography Volume 2, Monographs & Serials, by Subject This bibliography is a work in progress. It attempts to update Ronald B. De Waal’s comprehensive bibliography, The Universal Sherlock Holmes, but does not claim to be exhaustive in content. New works are continually discovered and added to this bibliography. Readers and researchers are invited to suggest additional content. The first volume in this supplement focuses on monographic and serial titles, arranged alphabetically by author or main entry. This second volume presents the exact same information arranged by subject. The subject headings used below are, for the most part, taken from the original De Waal bibliography. Some headings have been modified. Please use the bookmark function in your PDF reader to navigate through the document by subject categories. De Waal's major subject categories are: 1. The Sacred Writings 2. The Apocrypha 3. Manuscripts 4. Foreign Language Editions 5. The Literary Agent (Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) 6. The Writings About the Writings 7. Sherlockians and The Societies 8. Memorials and Memorabilia 9. Games, Puzzles and Quizzes 10. Actors, Performances and Recordings 11. Parodies, Pastiches, Burlesques, Travesties and Satires 12. Cartoons, Comics and Jokes The compiler wishes to thank Peter E. Blau, Don Hobbs, Leslie S. Klinger, and Fred Levin for their assistance in providing additional entries for this bibliography. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 01A SACRED WRITINGS -- INDIVIDUAL TALES -- A CASE OF IDENTITY (8) 1. Doyle, Arthur Conan. A Case of identity and other stories. -

PJ's Bookcase - All Pricing Is in Canadian Dollars

PJ's Bookcase - All pricing is in Canadian dollars. Shipping NOT included. Click on the Order page on our website to place your order and fill out the form. 1 Qty Inv. No. ISBN Author Title Publisher Category Type Cond. Additional Notes Sale Price 1 B2015-0002 978-1-4000-6617-9 Alda, Alan Things I Overheard While Talking to Myself Random House 200 Biography H E Autographed $15.00 Amos, Tori and Ann 1 B2016-0035A 0-7679-1676-X Tori Amos, Piece by Piece Broadway Books, NY, 2005 Biography H E $11.95 Powers 1 B2015-0006 0-445-04028-9 Andrews, Bart Story of I Love Lucy, The Popular Library 1977 Biography S G $2.00 1 B2015-0249 0-553-37972-0 Angelou, Maya Even the Stars Look Lonesome Bantam Books, N.Y. 1998 Biography ST VG $6.00 1 B2015-0005 0-553-38009-5 Angelou, Maya Heart of a Woman, The Bantam Books 1997 Biography ST VG $6.00 1 B2015-0185 0-553-38009-5 Angelou, Maya Heart of a Woman, The Bantam Books, 1997 Biography ST VG $6.00 1 B2015-0007 978-0-312-38104-2 Anka, Paul My Way - An Autobiography St. Martin's Press, 2013 Biography H E $12.00 1 B2015-0008 1-894662-36-5 Arden, Jann If I Knew, Don't You Think I'd Tell Ya? Insomniac Press 2002 Biography ST E $7.00 1 B2015-0009 978-0-670-06536-3 Baksi, Kurdo Stieg Larsson, My Friend Viking Canada 2010 Biography H E $8.50 1 B2015-0192 978-0-425-17731-0 Ball, Lucille Love, Lucy Berlkey Boulevard Books, 1997 Biography S E $4.00 1 B2015-0220 978-0-7710-7600-2 Barker, Edna (Editor) Remembering Peter Gzowki, A Book of Tributes McClelland & Stewart, 2002 Biography H E $7.00 The Windmill Press, Surrey, UK, 1 B2015-0273 No ISBN Barrymaine, Norman The Story of Peter Townsend Biography H G 2nd Printing $9.00 1958 PJ's Bookcase - All pricing is in Canadian dollars. -

News Parody, Valuations of the News Media, and Their

Perceived News Media Importance: News Parody, Valuations of the News Media, and Their Influence on Perceptions of Journalism Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason T. Peifer, M.A. Graduate Program in Communication The Ohio State University 2015 Committee: R. Kelly Garrett, Advisor R. Lance Holbert Gerald Kosicki Erik Nisbet Copyright by Jason T. Peifer 2015 Abstract Against the backdrop of declining public confidence in news media, this project explores the question of what could be contributing to increased skepticism toward the press and how the public’s apparent reluctance to express trust in news media might be interpreted by scholars. In an effort to address this basic query, this research effort is designed to (a) advance an understanding of news media perceptions, and (b) consider news parody’s role in influencing these perceptions. More specifically, this study explores the influence of news parody— conceptualized as a form of media criticism—on varied forms of media trust. By its very nature, news parody (such as The Daily Show and Last Week Tonight) is understood to offer both explicit and implicit commentary about the news media industry and media personnel. In so doing, it is argued here that news parody serves to endorse the notion of the news media serving important functions in society, even as the press may fail to meet its obligations. Furthermore, it is hypothesized that perceptions of news media importance have a meaningful influence on aspects of media trust.