Three Hundred Sixty Five Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

War Markets: the Neoliberal Theory

WAR MARKETS: THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY AND THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ___________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The College of Arts and Sciences Ohio University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Political Science ____________________________________ by Kiersten Lynn Arnoni June 2011 This thesis has been approved by the Department of Political Science and the College of Arts and Sciences ____________________________________ Professor of Political Science ____________________________________ Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Barry Tadlock for his support and guidance as my thesis advisor. Dr. Tadlock’s suggestions were valuable assets to this thesis. Abstract The neoliberal theory threatens permanent damage to American democracy. One guiding principle of theory is that the political marketplace is guided by market rationality. Also concentration of power resets with business and governing elites. As business norms begin to dominate politically, democratic ideals and laws equate only to tools and hurdles. Can the neoliberal theory help explain the situation of privatization and our military? Since the end of the Cold War, military size has been reduced, however, the need for military presence has not. The private war industry has begun to pick up the slack and private contractors have increased in areas needing military support. In Iraq, contractors make up the second largest contingent force, behind the U.S. military. Blackwater, or currently Xe Services LLC, is a powerful organization within the private war industry. Blackwater has accumulated over one billion dollars in contracts with the U.S. government. With the expanding use of private war contractors, their constitutionality comes into question. -

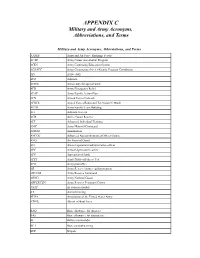

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Point Blank: Shooting Vietnamese Women Susan Jeffords

Vietnam Generation Volume 1 Number 3 Gender and the War: Men, Women and Article 14 Vietnam 10-1989 Point Blank: Shooting Vietnamese Women Susan Jeffords Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jeffords, Susan (1989) "Point Blank: Shooting Vietnamese Women," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 1 : No. 3 , Article 14. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol1/iss3/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Point BlANk: ShooTiNQ Vietnamese Women Susan JEffonds The single most popular image of women in combat available in contemporary U.S. dominant culture is that of Vietnamese women in Hollywood films about the Vietnam war. There are four general characterizations of Vietnamese women combatants1 that are specific to the issue of women and combat: one, they are single combatants: two, they do not fight by the rules of war; three, they do not accomplish large-scale missions: and four, they mutilate male bodies. As distinct from representations of men as combatants, Vietnamese women are depicted as single rather than group combatants. The saboteur in Apocalypse Now, the snipers in Full Metal Jacket and Paco’s Story, Rambo’s guide, or the NVA informant in “Tour of Duty” all fight alone.2 This is in keeping with Judith Ilicks Stiehm’s description of the general situation of women in the U.S. -

Sexual Orientation and US Military Personnel Policy

CORPORATION THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that POPULATION AND AGING helps improve policy and decisionmaking through PUBLIC SAFETY research and analysis. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. The monograph/report was a product of the RAND Corporation from 1993 to 2003. RAND monograph/reports presented major research findings that addressed the challenges facing the public and private sectors. They included executive summaries, technical documentation, and synthesis pieces. Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: Options and Assessment National Defense Research Institute R The research described in this report was sponsored by the Office of the Secretary of Defense under RAND’s National Defense Research Institute, a federally funded research and development center supported by the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Joint Staff, Contract No. -

The United States Marine Corps Scout/Snipers in Vietnam Honors

- Long Range Marines: The united states Marine Corps Scout/Snipers in Vietnam Honors 499 By: - Todd Smith Advisor: Dr. Tom Phelps Ball State University December 5, 1995 - - {' '- !:,,- , " ~. - 1 Introduction My Senior Honors Thesis is the cUlmination of my years at Ball State university. It shows both the knowledge I have gained and the lessons learned throughout this journey of education. This Thesis owes a great deal of thanks to several people. First and fore-most is Dr. Thomas Phelps of the History Department. As my advisor, he helped to create a work which I am pleased to have produced. Other persons who were helpful in this endeavor are Dr. Tony Edmonds and Dr. Phylis zimmerman, both of the History Department. Once again, special thanks to those people, as well as all those at Ball state who made my experience there so extremely pleasant. - - 2 There were a small group of highly trained soldiers who struck fear deep into the hearts of the North vietnamese forces in the vietnam War. These men stalked to their position, from which a single, well placed shot would ring out, and another enemy fell. These men were the Scout/Snipers of the United states Marine Corps. To understand the importance of these men, as well as the evolution of the military sniper, there are several things to be considered. In sniping, as in all history, it is necessary to examine the foundations which led to the American deployment of snipers in Vietnam. Sniping in general has always had a love/hate relationship in the military, a feeling which the Marines helped change. -

The Road to My Lai

THE ROAD TO MY LAI HUMBOLDT STATE UNIVERSITY By George F. Shaw A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Sociology Summer, 2012 ABSTRACT The U.S. military of the Vietnam era was a total institution of the Goffman school, set apart from larger American society, whose often forcibly inducted personnel underwent a transformative process from citizen to soldier. Comprised of a large group of individuals, with a common purpose, with a clear distinction between officers and enlisted, and regulated by a single authority, Goffman’s formulation as presented in the 1950’s has become a basic tenet of military sociology. The overwhelming evidence is clear: perhaps the best equipped army in history faced a debacle on the battlefield and cracked under minimal stress due to the internal rotation structure which was not resolved until the withdrawal of U.S. forces: the “fixed length tour”. Throughout the Vietnam War the duration of the tour in the combat theater was set at 12 months for Army enlisted, 13 months for Marine enlisted - officer ranks in both branches served six months in combat, six months on staff duty. The personnel turbulence generated by the “fixed length” combat tour and the finite Date of Estimated Return from Overseas (DEROS) created huge demands for replacement manpower among both enlisted and junior grade officers at the company and platoon level. It has been argued that just as a man was learning the ropes of combat in the jungles of Vietnam he was rotated out of the theater of operations. -

New Zealand and the Vietnam War

Fact sheet 6: New Zealand and the Vietnam War • Why did New Zealand fight in Vietnam? When the Second World War broke out in 1939 New Zealand declared in reference to Britain, 'Where she goes, we go; where she stands, we stand'. Until the Second World War Britain was our most significant ally but that conflict changed everything. Britain had been unable to halt Japan’s expansion in Asia during the war. New Zealand and Australia felt vulnerable. After the war New Zealand and Australia turned to the United States for added protection. In 1951 Australia, New Zealand and the US signed the ANZUS treaty. The US was keen to secure allies in its fight against the spread of communism. In 1954 New Zealand joined the US and Australia in signing the South-East Asia Collective Defence Treaty, or Manila Pact, another anti-communist alliance. Other signatories included France, Pakistan, the Philippines, Thailand and the United Kingdom. But these treaties did not force New Zealand to become involved in Vietnam. France and Britain, for example, did not participate in the war. The main reason for New Zealand’s involvement was the need to be seen to cooperate with our major ally, the US. • New Zealand’s contribution New Zealand's National government was cautious in its approach to Vietnam. Prime Minister Keith Holyoake didn’t question the morality of New Zealand involvement but he did doubt whether the war could be won. Our first response was to send a New Zealand Civilian Surgical Team to Qui Nhon in Binh Dinh province in 1963. -

Policy, Culture, and the Making of Love and War in Vietnam

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--History History 2015 FOREIGN AFFAIRS: POLICY, CULTURE, AND THE MAKING OF LOVE AND WAR IN VIETNAM Amanda C. Boczar University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Boczar, Amanda C., "FOREIGN AFFAIRS: POLICY, CULTURE, AND THE MAKING OF LOVE AND WAR IN VIETNAM" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--History. 27. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/27 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the History at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--History by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

(U) Remembering the Lessons of the Vietnam War Sharon A

DOCID: 3860879 SEC RE I /ICOMINTl/X I Cryptologic Quarterly (U) Remembering the Lessons of the Vietnam War Sharon A. Maneld (U) Although American cryptologists were ting in plain language. It was difficult to break this involved in the Vietnam War more than thirty tradition, especially because COMSEC methods years ago, their recollections are pertinent to the required additional time, trouble, and expense. cryptologists of today. In the current war on ter rorism, operations security (OPSEC) and commu (U) A second reason for difficulties in COM nications security (COMSEC), or information SEC enforcement was lack of emphasis by field assurance as it is called today, are just as vital to commanders. Frequently, the tactical comman success as they were during the Vietnam War. der received no training in COMSEC before going This article outlines the background of the OPSEC to South Vietnam. It was difficult to communicate and COMSEC problems faced by U.S. forces in the importance of COMSEC to a commander who Vietnam. The recollections of the various partici was trying to survive in the battlefield environ pants illustrate the complexities involved in trying ment. to solve these problems. Let us hope that the mis takes made in Vietnam can be avoided in the cur (U) Communicators devised their own cryp rent conflicts. tosystems because they found the approved sys tems too cumbersome and too time consuming. (U) Christmas Day in 1969 was a memorable They did not recognize the insecurities in their occasion for U.S. cryptologists involved with the homemade systems. Commanders could have Vietnam War. -

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Military

Journal of Law and Health Volume 24 Issue 1 Article 8 2011 Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Military: The Need for Legislative Improvement of Mental Health Care for Veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom Madeline McGrane Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/jlh Part of the Health Law and Policy Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Military, War, and Peace Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Note, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Military: The Need for Legislative Improvement of Mental Health Care for Veterans of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, 24 J.L. & Health 183 (2011) This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Health by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER IN THE MILITARY: THE NEED FOR LEGISLATIVE IMPROVEMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH CARE FOR VETERANS OF OPERATION IRAQI FREEDOM AND OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM MADELINE MCGRANE* I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 184 II. OVERVIEW OF PTSD AND THE UNITED STATES MILITARY.. 185 A. PTSD: Definition and Treatment................................. 186 B. Traumatic Brain Injury................................................ 189 C. Problems Resulting from Undiagnosed PTSD ............ 189 D. Reasons PTSD is Frequently Undiagnosed................. 191 E. Stumbling Blocks for Receiving Treatment: Denial of Coverage and Inadequate Health Care Facilities ...................................................................... 193 III. CONGRESSIONAL AND MILITARY SOLUTIONS ...................... 196 A. The Joshua Omvig Veterans Suicide Prevention Act................................................................................ 196 B. Other Acts.................................................................... 197 C. -

The Hero Industry: Spectacular Pacification in the Era of Media Interactivity

Occam's Razor Volume 10 (2020) Article 5 2020 The Hero Industry: Spectacular Pacification in the Era of Media Interactivity Braden Timss Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu Part of the Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons Recommended Citation Timss, Braden (2020) "The Hero Industry: Spectacular Pacification in the Era of Media Interactivity," Occam's Razor: Vol. 10 , Article 5. Available at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/orwwu/vol10/iss1/5 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Western Student Publications at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occam's Razor by an authorized editor of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Timss: The Hero Industry: Spectacular Pacification in the Era of Media I THE HERO INDUSTRY Spectacular Pacification in the Era of Media Interactivity By Braden Timss INTRODUCTION: THE SPECTACLE, SITUATIONS, AND THE VIRTUAL CITIZEN-SOLDIER n Ben Fountain’s 2012 novel, Billy Lynn’s Long Half- Entangled in the complex inter- time Walk, the titular US soldier and the Bravo squad play between war, mass media, and Ibecome canonized Iraq War heroes when their rescue capitalism, the process of American attempt is captured on digital video. In recognition of hero commodification undergone by their bravery, their tour of duty is halted for an American figures like Billy Lynn can be demy- media stint that culminates in their participation during stified with consideration for Guy the 2004 Dallas Cowboys Thanksgiving halftime show. Debord’s theory of the spectacle. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper aligmnent can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if imauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, begiiming at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313,'761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9401312 The Vietnam war on prime time television: Focus group aided rhetorical criticism of American myths in “Tour of Duty” and “China Beach” Marshall, Scott Wayne, Ph.D.