Vietnam War: Going After Cacciato & Its Historical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Combat Motivation in the Iraq War

WHY THEY FIGHT: COMBAT MOTIVATION IN THE IRAQ WAR Leonard Wong Thomas A. Kolditz Raymond A. Millen Terrence M. Potter July 2003 ***** The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. This report is cleared for public release; distribution is unlimited. ***** This study was greatly supported by members of the 800th Military Police Brigade -- specifically BG Paul Hill, COL Al Ecke, and LTC James O’Hare. Staff Judge Advocates COL Ralph Sabbatino and COL Karl Goetzke also provided critical guidance. Finally, COL Jim Embrey planned and coordinated the visits to units for this study. ***** Comments pertaining to this report are invited and should be forwarded to: Director, Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 122 Forbes Ave, Carlisle, PA 17013-5244, or directly to [email protected] Copies of this report may be obtained from the Publications Office by calling (717) 245-4133, FAX (717) 245-3820, or by e-mail at [email protected] ***** All Strategic Studies Institute (SSI) monographs are available on the SSI Homepage for electronic dissemination. SSI’s Homepage address is: http:// www.carlisle.army.mil/ssi/ ***** The Strategic Studies Institute publishes a monthly e-mail newsletter to update the national security community on the research of our analysts, recent and forthcoming publications, and upcoming conferences sponsored by the Institute. Each newsletter also provides a strategic commentary by one of our research analysts. If you are interested in receiving this newsletter, please let us know by e-mail at [email protected] or by calling (717) 245-3133. -

Three Hundred Sixty Five Days

Three Hundred and Sixty Five Days With Letters to Home By Paul T. Kearns INTRODUCTION What follows is a narrative of my personal experience as a helicopter pilot serving in the U.S. Army in the Republic of South Vietnam during the years 1968- 1969, and portions of my army flight training experiences prior to my combat duty service in Vietnam. It is a recollection of what I experienced then, and can recall now, some thirty five years later. History books tell the facts concerning the battles and politics of that war, what led up to it, how it was won or lost, and how it ended. My perspective, described herein, is much more limited and personal. It is my story, and to a limited degree, a story of others who shared the three hundred and sixty five day tour of duty with me. This version of my memoir has excerpts taken from personal letters I wrote to my family during this period. MY ARRIVAL The date was May 30, 1968. It had been a very long flight from McCord Air Force Base in Seattle, Washington to Cam Rahn Bay Air Force Base in South Vietnam. I was 21 years old, three weeks past my graduation from the United States Army Aviation School at Fort Rucker, Alabama. The moment that I stepped off that airplane I was the newest arrival amongst the steady stream of mostly young men going to Vietnam to join the occupational army consisting of some 500,000 Americans. I was scared, and very lonely. Almost to the day, three years earlier, I had walked down the isle at La Jolla High School in San Diego, California to receive my diploma. -

W Vietnam Service Report

Honoring Our Vietnam War and Vietnam Era Veterans February 28, 1961 - May 7, 1975 Town of West Seneca, New York Name: WAILAND Hometown: CHEEKTOWAGA FRANK J. Address: Vietnam Era Vietnam War Veteran Year Entered: 1968 Service Branch:ARMY Rank: SP-5 Year Discharged: 1971 Unit / Squadron: 1ST INFANTRY DIVISION 1ST ENGINEER BATTALION Medals / Citations: NATIONAL DEFENSE SERVICE RIBBON VIETNAM SERVICE MEDAL VIETNAM CAMPAIGN MEDAL WITH '60 DEVICE ARMY COMMENDATION MEDAL 2 OVERSEAS SERVICE BARS SHARPSHOOTER BADGE: M-16 RIFLE EXPERT BADGE: M-14 RIFLE Served in War Zone Theater of Operations / Assignment: VIETNAM Service Notes: Base Assignments: Fort Belvoir, Virginia - The base was founded during World War I as Camp A. A. Humphreys, named for Union Civil War general Andrew A. Humphreys, who was also Chief of Engineers / The post was renamed Fort Belvoir in the 1930s in recognition of the Belvoir plantation that once occupied the site, but the adjacent United States Army Corps of Engineers Humphreys Engineer Center retains part of the original name / Fort Belvoir was initially the home of the Army Engineer School prior to its relocation in the 1980s to Fort Leonard Wood, in Missouri / Fort Belvoir serves as the headquarters for the Defense Logistics Agency, the Defense Acquisition University, the Defense Contract Audit Agency, the Defense Technical Information Center, the United States Army Intelligence and Security Command, the United States Army Military Intelligence Readiness Command, the Missile Defense Agency, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, all agencies of the United States Department of Defense Lai Khe, Vietnam - Also known as Lai Khê Base, Lai Khe was a former Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and U.S. -

"So God-Damned Far Away": Soldiers' Experiences in the Vietnam War

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 5-9-2012 "So God-damned Far Away": Soldiers' Experiences in the Vietnam War Tara M. Bell [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bell, Tara M., ""So God-damned Far Away": Soldiers' Experiences in the Vietnam War" (2012). Honors Theses. 1542. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/1542 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY The Carl and Winifred Lee Honors College THE CARL AND WINIFRED LEE HONORS COLLEGE CERTIFICATE OF ORAL DEFENSE OF HONORS THESIS Tara Bell, having been admitted to the Carl and Winifred Lee Honors College in the fall of 2008, successfully completed the Lee Honors College Thesis on May 09, 2012. The title of the thesis is: "So God-damned Far Away": Soldiers'Experiences in the Vietnam War Dr. Edwin Martini, History Scott Friesner, Lee Honors College Dr. Nicholas Andreadis, Lee Honors College 1903 W. Michigan Ave., Kalamazoo, Ml 49008-5244 PHONE: (269) 387-3230 FAX: (269) 387-3903 www.wmich.edu/honors The story of the Vietnam War cannot be told solely from the perspective of the political and military leaders of the war. For a complete understanding of the war one must look at the experiences of the common person, the soldiers who fought in the war. -

Combined Action Platoons: a Strategy for Peace Enforcement

Combined Action Platoons: A Strategy for Peace Enforcement CSC 1996 SUBJECT AREA Strategic Issues EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Title: Combined Action Platoons: A Strategy for Peace Enforcement Author: Major Brooks R. Brewington, United States Marine Corps Thesis: The concept of the Combined Action Platoon, as it evolved in Vietnam, has potential applications in operations other than war, particularly Chapter VII UN Peace Enforcement missions. FMFM 1-1, Campaigning, cites the Combined Action Program as an example of a short-lived but successful concept. If the Combined Action Platoons were successful, then how would the concept interface with today's doctrine in Peace Keeping/Enforcement missions? Discussion: Earlier this century, the Marine Corps was often called "State Department's troops," and during the 1960's the term "Ambassadors in Green" was used. As the budget dictates a smaller force with no foreseeable respite in overseas commitments, the Marines are searching for a model to handle this challenge. Operations such as those conducted in Somalia, Haiti, and Bosnia are becoming the norm and provide an environment for a CAP-style operation to be successfully employed. Sea Dragon may be the Marine Corp's second generation of a CAP-style operation that handles the challenges of reduction in forces and commitments. The lessons learned from the CAP experience is that the use of firepower is only half of the pacification equation. The other half, as highlighted in the Small Wars Manual, is, in order to have long-term success, winning the trust of the indiginous population is a priority and must occur. For a short time in Vietnam, the Combined Action Program did just that by denying the enemy a safe haven in the local village and hamlets. -

Problem Soldier"- Dissenter in the Ranks

Indiana Law Journal Volume 49 Issue 4 Article 6 Summer 1974 The New "Problem Soldier"- Dissenter in the Ranks Howard J. De Nike Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Military, War, and Peace Commons Recommended Citation De Nike, Howard J. (1974) "The New "Problem Soldier"- Dissenter in the Ranks," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 49 : Iss. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol49/iss4/6 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMPOSIUM THE NEW "PROBLEM SOLDIER"-DISSENTER IN THE RANKS HOWARD J. DE NIKEt In days gone past, the professional military planner often spoke of the "problem soldier." This was the GI who was difficult to teach, who became a discipline problem, and who, in the commander's opinion, de- manded an inordinate amount of attention. With increasing frequency the "problem soldier" is viewed by com- mand personnel within today's military as "the dissenting soldier."' The Vietnam era in particular witnessed a widespread interest among active duty military personnel, from all services, in the exercise of first amend- ment rights. The controversy surrounding the Vietnam war also brought intense civilian interest in both the military and constitutional rights of, pri- marily, enlisted personnel. There have been significant court decisions which have bolstered these rights and which, consequently, are now em- bedded in the foundation upon which the structure of the post-Vietnam United States military will be erected There are substantial signs that the exercise of rights of expression and association among servicemen and women has not flagged since the termination of the United States combat role in Vietnam. -

War Markets: the Neoliberal Theory

WAR MARKETS: THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY AND THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ___________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The College of Arts and Sciences Ohio University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Political Science ____________________________________ by Kiersten Lynn Arnoni June 2011 This thesis has been approved by the Department of Political Science and the College of Arts and Sciences ____________________________________ Professor of Political Science ____________________________________ Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Barry Tadlock for his support and guidance as my thesis advisor. Dr. Tadlock’s suggestions were valuable assets to this thesis. Abstract The neoliberal theory threatens permanent damage to American democracy. One guiding principle of theory is that the political marketplace is guided by market rationality. Also concentration of power resets with business and governing elites. As business norms begin to dominate politically, democratic ideals and laws equate only to tools and hurdles. Can the neoliberal theory help explain the situation of privatization and our military? Since the end of the Cold War, military size has been reduced, however, the need for military presence has not. The private war industry has begun to pick up the slack and private contractors have increased in areas needing military support. In Iraq, contractors make up the second largest contingent force, behind the U.S. military. Blackwater, or currently Xe Services LLC, is a powerful organization within the private war industry. Blackwater has accumulated over one billion dollars in contracts with the U.S. government. With the expanding use of private war contractors, their constitutionality comes into question. -

Martial Brilliance Or Marine Corps Propaganda? the Combined Action Platoon in the Vietnam War

Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History Volume 9 Issue 2 Article 8 11-2019 Martial Brilliance or Marine Corps Propaganda? The Combined Action Platoon in the Vietnam War Beta Scarpaci Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/aujh Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Scarpaci, Beta (2019) "Martial Brilliance or Marine Corps Propaganda? The Combined Action Platoon in the Vietnam War," Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. DOI: 10.20429/aujh.2019.090208 Available at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/aujh/vol9/iss2/8 This article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Armstrong Undergraduate Journal of History by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Scarpaci: Martial Brilliance or Marine Corps Propaganda? Martial Brilliance or Marine Corps Propaganda? The Combined Action Platoon in the Vietnam War Bret Scarpaci Marquette University (Milwaukee, Wisconsin) Historians and military thinkers alike are fascinated with the Vietnam War given its status as one of the few engagements in American military history in which the United States failed to achieve its strategic and political policy objectives. Much attention is paid to the military policies implemented during the war aimed at neutralizing the guerilla threat, propping up the government in Saigon, and pacifying South Vietnam. The prevailing strategy during the war, Search and Destroy, was championed by political and military leaders alike. The strategy is nearly self-explanatory; conventional line units would conduct operations throughout the jungles, hills, and rice paddies of South Vietnam with one goal in mind: to make contact with and destroy the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) units operating in the region. -

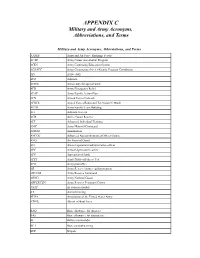

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Ideological, Dystopic, and Antimythopoeic Formations of Masculinity in the Vietnam War Film Elliott Stegall

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Ideological, Dystopic, and Antimythopoeic Formations of Masculinity in the Vietnam War Film Elliott Stegall Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES IDEOLOGICAL, DYSTOPIC, AND ANTIMYTHOPOEIC FORMATIONS OF MASCULINITY IN THE VIETNAM WAR FILM By ELLIOTT STEGALL A Dissertation submitted to the Program in Interdisciplinary Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2014 Elliott Stegall defended this dissertation on October 21, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: John Kelsay Professor Directing Dissertation Karen Bearor University Representative Kathleen Erndl Committee Member Leigh Edwards Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am most grateful for my wife, Amanda, whose love and support has made all of this possible; for my mother, a teacher, who has always been there for me and who appreciates a good conversation; to my late father, a professor of humanities and religion who allowed me full access to his library and record collection; and, of course, to the professors who have given me their insight and time. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures................................................................................................................................. v Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………...... vi 1. VIETNAM MOVIES, A NEW MYTHOS OF THE MASCULINE......................................... 1 2. DISPELLING FILMIC MYTHS OF THE VIETNAM WAR……………………………... 24 3. IN DEFENSE OF THE GREEN BERETS ………………………………………………..... -

The Armylawyer

THE ARMY LAWYER Headquarters, Department of the Army November 2011 ARTICLES Conquering Competency and Other Professional Responsibility Pointers for Appellate Practitioners Major Jay L. Thoman Rule of Law in Iraq and Afghanistan? Mark Martins USALSA REPORT Trial Judiciary Note A View from the Bench: Immunizing Witnesses Colonel R. Peter Masterton TJAGLCS FEATURES Lore of the Corps A “Fragging” in Vietnam: The Story of a Court-Martial for Attempted Murder and Its Aftermath New Developments Administrative & Civil Law The Army Safety Program Major Derek D. Brown BOOK REVIEWS How We Decide Reviewed by Major Keith A. Petty CLE NEWS CURRENT MATERIALS OF INTEREST Department of the Army Pamphlet 27-50-462 Editor, Captain Joseph D. Wilkinson II Technical Editor, Charles J. Strong The Army Lawyer (ISSN 0364-1287, USPS 490-330) is published monthly The Judge Advocate General’s School, U.S. Army. The Army Lawyer by The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, Charlottesville, welcomes articles from all military and civilian authors on topics of interest to Virginia, for the official use of Army lawyers in the performance of their military lawyers. Articles should be submitted via electronic mail to legal responsibilities. Individual paid subscriptions to The Army Lawyer are [email protected]. Articles should follow The available for $45.00 each ($63.00 foreign) per year, periodical postage paid at Bluebook, A Uniform System of Citation (19th ed. 2010) and the Military Charlottesville, Virginia, and additional mailing offices (see subscription form Citation Guide (TJAGLCS, 16th ed. 2011). No compensation can be paid for on the inside back cover). -

Volume 195 Spring 2008 ARTICLES BOOK REVIEWS Department of Army Pamphlet 27-100-195

Volume 195 Spring 2008 ARTICLES TIME TO KILL: EUTHANIZING THE REQUIREMENT FOR PRESIDENTIAL APPROVAL OF MILITARY DEATH SENTENCES TO RESTORE FINALITY OF LEGAL REVIEW Major Joshua M. Toman THE SOLDIER AND THE STATE: WHETHER THE ABROGATION OF STATE SOVEREIGN IMMUNITY IN USERRA ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS IS A VALID EXERCISE OF THE CONGRESSIONAL WAR POWERS Major Timothy M. Harner BY THE CONTENT OF CHARACTER: THE LIFE AND LEADERSHIP OF MAJOR GENERAL KENNETH D. GRAY (RET.) (1966–1997), THE FIRST AFRICAN-AMERICAN JUDGE ADVOCATE GENERAL OFFICER Lieutenant Colonel George R. Smawley THE THIRTY-SIXTH KENNETH J. HODSON LECTURE ON CRIMINAL LAW Brigadier General Patrick P. Finnegan BOOK REVIEWS Department of Army Pamphlet 27-100-195 i MILITARY LAW REVIEW Volume 195 Spring 2008 CONTENTS ARTICLES Time to Kill: Euthanizing the Requirement for Presidential Approval of Military Death Sentences to Restore Finality of Legal Review Major Joshua M. Toman 1 The Soldier and the State: Whether the Abrogation of State Sovereign Immunity in USERRA Enforcement Actions Is a Valid Exercise of the Congressional War Powers Major Timothy M. Harner 91 By the Content of Character: The Life and Leadership of Major General Kenneth D. Gray (Ret.) (1966–1997), The First African-American Judge Advocate General Officer Lieutenant Colonel George R. Smawley 128 The Thirty-Sixth Kenneth J. Hodson Lecture on Criminal Law Brigadier General Patrick P. Finnegan 190 BOOK REVIEWS The Looming Tower: Al-Qaeda and the Road to 9/11 Reviewed by Major Jeffrey S. Thurnher 203 The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC Reviewed by Major Brian Harlan 211 i Headquarters, Department of the Army, Washington, D.C.