The Hero Industry: Spectacular Pacification in the Era of Media Interactivity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

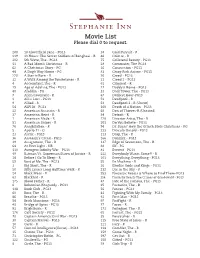

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

Bigelow Masculinity

Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Article TOUGH GUY IN DRAG? HOW THE EXTERNAL, CRITICAL DISCOURSES SURROUNDING KATHRYN BIGELOW DEMONSTRATE THE WIDER PROBLEMS OF THE GENDER QUESTION. RONA MURRAY, De Montford University ABSTRACT This article argues that the various approaches adopted towards Kathryn Bigelow’s work, and their tendency to focus on a gendered discourse, obscures the wider political discourses these texts contain. In particular, by analysing the representation of masculinity across the films, it is possible to see how the work of this director and her collaborators is equally representative of its cultural context and how it uses the trope of the male body as a site for a dialectical study of the uses and status of male strength within an imperialistically-minded western society. KEYWORDS Counter-cultural, feminism, feminist, gender, masculinity, western. ISSN 1755-9944 1 Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network, Vol. 4, No. 1 (2011) Whether the director Kathryn Bigelow likes it or not, gender has been made to lie at the heart of her work, not simply as it figures in her texts but also as it is used to initiate discussion about her own function/place as an auteur? Her career illustrates how the personal becomes the political not via individual agency but in the way she has come to stand as a particular cultural symbol – as a woman directing men in male-orientated action genres. As this persona has become increasingly loaded with various significances, it has begun to alter the interpretations of her films. -

And American Sniper (2014) Representation, Reflectionism and Politics

UFR Langues, Littératures et Civilisations Étrangères Département Études du Monde Anglophone Master 2 Recherche, Études Anglophones The Figure of the Soldier in Green Zone (2010) and American Sniper (2014) Representation, Reflectionism and Politics Mémoire présenté et soutenu par Lucie Pebay Sous la direction de Zachary Baqué et David Roche Assesseur: Aurélie Guillain Septembre 2016 1 The Figure of the Soldier in Green Zone (2010) and American Sniper (2014) Representation, Reflectionism and Politics. 2 I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have made this thesis possible. I would like to thank Zachary Baqué and David Roche, for the all the help, patience, guidance, and advice they have provided me throughout the year. I have been extremely lucky to have supervisors who cared so much about my work, and who responded to my questions and queries so promptly. I would also like to acknowledge friends and family who were a constant support. 3 Table of Content Introduction..........................................................................................................................................5 I- Screening the Military....................................................................................................................12 1. Institutions.................................................................................................................................12 a. The Army, a Heterotopia.......................................................................................................12 b. -

Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker"

Cinesthesia Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 1 12-1-2012 Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The urH t Locker" Kelly Meyer Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Kelly (2012) "Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The urH t Locker"," Cinesthesia: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cine/vol1/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cinesthesia by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meyer: Cinematic Realism in Bigelow's "The Hurt Locker" Cinematic Realism in Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker No one has ever seen Baghdad. At least not like explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) squad leader William James has, through a lens of intense adrenaline and deathly focus. In the 2008 film The Hurt Locker, director Katherine Bigelow creates a striking realist portrait of an EOD team on their tour of Baghdad. Bigelow’s use of deep focus and wide- angle shots in The Hurt Locker exemplify the realist concerns of French film theorist André Bazin. Early film theory has its basis in one major goal: to define film as art in its own right. In What is Film Theory, authors Richard Rushton and Gary Bettinson state that “…each theoretical inquiry converges on a common objective: to defend film as a distinctive and authentic mode of art” (8). Many theorists argue relevant and important points regarding film, some from a formative point of view and others from a realist view. -

Film & Literature

Name_____________________ Date__________________ Film & Literature Mr. Corbo Film & Literature “Underneath their surfaces, all movies, even the most blatantly commercial ones, contain layers of complexity and meaning that can be studied, analyzed and appreciated.” --Richard Barsam, Looking at Movies Curriculum Outline Form and Function: To equip students, by raising their awareness of the development and complexities of the cinema, to read and write about films as trained and informed viewers. From this base, students can progress to a deeper understanding of film and the proper in-depth study of cinema. By the end of this course, you will have a deeper sense of the major components of film form and function and also an understanding of the “language” of film. You will write essays which will discuss and analyze several of the films we will study using accurate vocabulary and language relating to cinematic methods and techniques. Just as an author uses literary devices to convey ideas in a story or novel, filmmakers use specific techniques to present their ideas on screen in the world of the film. Tentative Film List: The Godfather (dir: Francis Ford Coppola); Rushmore (dir: Wes Anderson); Do the Right Thing (dir: Spike Lee); The Dark Knight (dir: Christopher Nolan); Psycho (dir: Alfred Hitchcock); The Graduate (dir: Mike Nichols); Office Space (dir: Mike Judge); Donnie Darko (dir: Richard Kelly); The Hurt Locker (dir: Kathryn Bigelow); The Ice Storm (dir: Ang Lee); Bicycle Thives (dir: Vittorio di Sica); On the Waterfront (dir: Elia Kazan); Traffic (dir: Steven Soderbergh); Batman (dir: Tim Burton); GoodFellas (dir: Martin Scorsese); Mean Girls (dir: Mark Waters); Pulp Fiction (dir: Quentin Tarantino); The Silence of the Lambs (dir: Jonathan Demme); The Third Man (dir: Carol Reed); The Lord of the Rings trilogy (dir: Peter Jackson); The Wizard of Oz (dir: Victor Fleming); Edward Scissorhands (dir: Tim Burton); Raiders of the Lost Ark (dir: Steven Spielberg); Star Wars trilogy (dirs: George Lucas, et. -

Three Hundred Sixty Five Days

Three Hundred and Sixty Five Days With Letters to Home By Paul T. Kearns INTRODUCTION What follows is a narrative of my personal experience as a helicopter pilot serving in the U.S. Army in the Republic of South Vietnam during the years 1968- 1969, and portions of my army flight training experiences prior to my combat duty service in Vietnam. It is a recollection of what I experienced then, and can recall now, some thirty five years later. History books tell the facts concerning the battles and politics of that war, what led up to it, how it was won or lost, and how it ended. My perspective, described herein, is much more limited and personal. It is my story, and to a limited degree, a story of others who shared the three hundred and sixty five day tour of duty with me. This version of my memoir has excerpts taken from personal letters I wrote to my family during this period. MY ARRIVAL The date was May 30, 1968. It had been a very long flight from McCord Air Force Base in Seattle, Washington to Cam Rahn Bay Air Force Base in South Vietnam. I was 21 years old, three weeks past my graduation from the United States Army Aviation School at Fort Rucker, Alabama. The moment that I stepped off that airplane I was the newest arrival amongst the steady stream of mostly young men going to Vietnam to join the occupational army consisting of some 500,000 Americans. I was scared, and very lonely. Almost to the day, three years earlier, I had walked down the isle at La Jolla High School in San Diego, California to receive my diploma. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Cheers! 'Stuttgarter Weindorf'

MORE ONLINE: Visit StuttgartCitizen.com and sign up for the daily email for more timely announcements NEWS FEATURE HEALTH BEAT FORCES UNITE ARE YOU PREPARED? New science-based techno- U.S. Marine Forces Europe and How to be ready in the event logy to reach and sustain a Africa unite with a new commander. — PAGE 2 of an emergency. — PAGES 12-13 healthy weight. — PAGE 10 FLAKKASERNE REMEMBERED Ludwigsburg to honor the service of U.S. Armed Forces with plaque unveiling and free entrance to Garrison Museum and Ludwigsburg Palace Sept. 13. — PAGE 3 Thursday, September 3, 2015 Sustaining & Supporting the Stuttgart U.S. Military Community Garrison Website: www.stuttgart.army.mil Facebook: facebook.com/USAGarrisonStuttgart stuttgartcitizen.com Cheers! ‘Stuttgarter Weindorf’ Only a few days left to enjoy a swell time at local wine fest. — Page 5 Photos courtesy of Regio Stuttgart Marketing-und Tourismus GmbH Tourismus Stuttgart Marketing-und Photos courtesy of Regio NEWS ANNOUNCEMENTS GOING GREEN ASK A JAG 709th Military Police Battalion Löwen Award Community news updates including closures Federal Procurement programs require purchases What newcomers need to know about fi ling presented to outstanding FRG leader of 554th and service changes, plus fun activities of 'green' products and services. claims for household goods, vehicles and Military Police Company. — PAGE 8 coming up at the garrison. — PAGE 6-7 — PAGE 4 more. — PAGE 4 Page 2 NEWS The Citizen, September 3, 2015 is newspaper is an authorized publication for members of the Department of Defense. Contents of e Citizen are not necessarily the o cial views of, or Marines across continents unite endorsed by, the U.S. -

January and February

VIETNAM VETERANS OF AMERICA Office of the National Chaplain FOUAD KHALIL AIDE -- Funeral service for Major Fouad Khalil Aide, United States Army (Retired), 78, will be Friday, November 13, 2009, at 7 p.m. at the K.L. Brown Funeral Home and Cremation Center Chapel with Larry Amerson, Ken Rollins, and Lt. Col. Don Hull officiating, with full military honors. The family will receive friends Friday evening from 6-7 p.m. at the funeral home. Major Aide died Friday, November 6, 2009, in Jacksonville Alabama. The cause of death was a heart attack. He is survived by his wife, Kathryn Aide, of Jacksonville; two daughters, Barbara Sifuentes, of Carrollton, Texas, and Linda D'Anzi, of Brighton, England; two sons, Lewis Aide, of Columbia, Maryland, and Daniel Aide, of Springfield, Virginia, and six grandchildren. Pallbearers will be military. Honorary pallbearers will be Ken Rollins, Matt Pepe, Lt. Col. Don Hull, Jim Hibbitts, Jim Allen, Dan Aide, Lewis Aide, VVA Chapter 502, and The Fraternal Order of Police Lodge. Fouad was commissioned from the University of Texas ROTC Program in 1953. He served as a Military Police Officer for his 20 years in the Army. He served three tours of duty in Vietnam, with one year as an Infantry Officer. He was recalled to active duty for service in Desert Shield/Desert Storm. He was attached to the FBI on their Terrorism Task Force because of his expertise in the various Arabic dialects and cultures. He was fluent in Arabic, Spanish and Vietnamese and had a good working knowledge of Italian, Portuguese and French. -

War Markets: the Neoliberal Theory

WAR MARKETS: THE NEOLIBERAL THEORY AND THE UNITED STATES MILITARY ___________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The College of Arts and Sciences Ohio University ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors in Political Science ____________________________________ by Kiersten Lynn Arnoni June 2011 This thesis has been approved by the Department of Political Science and the College of Arts and Sciences ____________________________________ Professor of Political Science ____________________________________ Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Barry Tadlock for his support and guidance as my thesis advisor. Dr. Tadlock’s suggestions were valuable assets to this thesis. Abstract The neoliberal theory threatens permanent damage to American democracy. One guiding principle of theory is that the political marketplace is guided by market rationality. Also concentration of power resets with business and governing elites. As business norms begin to dominate politically, democratic ideals and laws equate only to tools and hurdles. Can the neoliberal theory help explain the situation of privatization and our military? Since the end of the Cold War, military size has been reduced, however, the need for military presence has not. The private war industry has begun to pick up the slack and private contractors have increased in areas needing military support. In Iraq, contractors make up the second largest contingent force, behind the U.S. military. Blackwater, or currently Xe Services LLC, is a powerful organization within the private war industry. Blackwater has accumulated over one billion dollars in contracts with the U.S. government. With the expanding use of private war contractors, their constitutionality comes into question. -

Rehearsing the “Warrior Ethos”

Rehearsing the “Warrior Ethos” “Theatre Immersion” and the Simulation of Theatres of War Scott Magelssen As America’s embedment in the Middle East has become increasingly entrenched, complicated, and violent, the Armed Forces are looking to theatre and performance for new counterinsur- gency strategies to keep apace with the shifting specificities of the present war.1 To pre-expose deployment-bound troops to combatants’ unconventional tactics, and to the sharp-eyed gaze of the local and international media, the Army has constructed vast simulations of wartime Iraq and Afghanistan. Termed “Theatre Immersions,”2 these sites feature entire villages—living, breath- ing environments complete with residential, government, retail, and worship districts—bustling 1. It should be said that, whereas the military uses “strategies” to denote overall plans to win a war, and “tactics” to denote the practices used in the field to implement these strategies (Mockaitis 2007b), I use these terms in the sense articulated by Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life (1984). To paraphrase de Certeau, strategies are the methods used by those in power to rein in and police the space they control, and tactics are used by those to whom the space does not belong, but who occupy it and maneuver through its landscape, resisting or playing by its rules. In this case, the US and Coalition forces, in cooperation with the interim and permanent govern- ments, ostensibly own and control the space of Iraq, and operate strategically to maintain this control. 2. “Theater immersion rapidly builds combat-ready formations led by competent, confident leaders who see first, understand first, and act first; battleproofed soldiers inculcated with the warrior ethos man the formations. -

European Journal of American Studies, 12-2 | 2017 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl

European journal of American studies 12-2 | 2017 Summer 2017, including Special Issue: Popularizing Politics: The 2016 U.S. Presidential Election “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/12086 DOI: 10.4000/ejas.12086 ISSN: 1991-9336 Publisher European Association for American Studies Electronic reference Lennart Soberon, ““The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre”, European journal of American studies [Online], 12-2 | 2017, document 12, Online since 01 August 2017, connection on 08 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ ejas/12086 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ejas.12086 This text was automatically generated on 8 July 2021. Creative Commons License “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Gl... 1 “The Old Wild West in the New Middle East”: American Sniper (2014) and the Global Frontiers of the Western Genre Lennart Soberon 1 While recent years have seen no shortage of American action thrillers dealing with the War on Terror—Act of Valor (2012), Zero Dark Thirty (2012), and Lone Survivor (2013) to name just a few examples—no film has been met with such a great controversy as well as commercial success as American Sniper (2014). Directed by Clint Eastwood and based on the autobiography of the most lethal sniper in U.S. military history, American Sniper follows infamous Navy Seal Chris Kyle throughout his four tours of duty to Iraq.