Arxiv:1712.04750V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 13 Dec 2017 Ftefeunyo Aiu Irrhe Ntefil.But field

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luminous Blue Variables

Review Luminous Blue Variables Kerstin Weis 1* and Dominik J. Bomans 1,2,3 1 Astronomical Institute, Faculty for Physics and Astronomy, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2 Department Plasmas with Complex Interactions, Ruhr University Bochum, 44801 Bochum, Germany 3 Ruhr Astroparticle and Plasma Physics (RAPP) Center, 44801 Bochum, Germany Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 18 February 2020; Published: 29 February 2020 Abstract: Luminous Blue Variables are massive evolved stars, here we introduce this outstanding class of objects. Described are the specific characteristics, the evolutionary state and what they are connected to other phases and types of massive stars. Our current knowledge of LBVs is limited by the fact that in comparison to other stellar classes and phases only a few “true” LBVs are known. This results from the lack of a unique, fast and always reliable identification scheme for LBVs. It literally takes time to get a true classification of a LBV. In addition the short duration of the LBV phase makes it even harder to catch and identify a star as LBV. We summarize here what is known so far, give an overview of the LBV population and the list of LBV host galaxies. LBV are clearly an important and still not fully understood phase in the live of (very) massive stars, especially due to the large and time variable mass loss during the LBV phase. We like to emphasize again the problem how to clearly identify LBV and that there are more than just one type of LBVs: The giant eruption LBVs or h Car analogs and the S Dor cycle LBVs. -

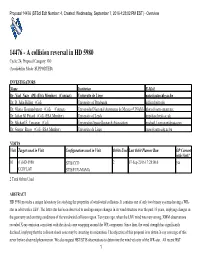

14476 (Stsci Edit Number: 4, Created: Wednesday, September 7, 2016 4:28:02 PM EST) - Overview

Proposal 14476 (STScI Edit Number: 4, Created: Wednesday, September 7, 2016 4:28:02 PM EST) - Overview 14476 - A collision reversal in HD 5980 Cycle: 24, Proposal Category: GO (Availability Mode: SUPPORTED) INVESTIGATORS Name Institution E-Mail Dr. Yael Naze (PI) (ESA Member) (Contact) Universite de Liege [email protected] Dr. D. John Hillier (CoI) University of Pittsburgh [email protected] Dr. Gloria Koenigsberger (CoI) (Contact) Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM) [email protected] Dr. Julian M. Pittard (CoI) (ESA Member) University of Leeds [email protected] Dr. Michael F. Corcoran (CoI) Universities Space Research Association [email protected] Dr. Gregor Rauw (CoI) (ESA Member) Universite de Liege [email protected] VISITS Visit Targets used in Visit Configurations used in Visit Orbits Used Last Orbit Planner Run OP Current with Visit? 01 (1) HD-5980 STIS/CCD 2 07-Sep-2016 17:28:00.0 yes CCDFLAT STIS/FUV-MAMA 2 Total Orbits Used ABSTRACT HD 5980 provides a unique laboratory for studying the properties of wind-wind collisions. It contains one of only two binary systems having a WR- star in orbit with a LBV. The latter star has been observed to undergo major changes in its wind structure over the past 35 years, implying changes in the geometry and emitting conditions of the wind-wind collision region. Ten years ago, when the LBV wind was very strong, XMM observations revealed X-ray emission consistent with the shock cone wrapping around the WR component. Since then, the wind strength has significantly declined, implying that the collision shock cone may be inverting its orientation. -

Fundamental Parameters of Wolf-Rayet Stars VI

Astron. Astrophys. 320, 500–524 (1997) ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS Fundamental parameters of Wolf-Rayet stars VI. Large Magellanic Cloud WNL stars? P.A.Crowther and L.J. Smith Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK Received 5 February 1996 / Accepted 26 June 1996 Abstract. We present a detailed, quantitative study of late WN Key words: stars: Wolf-Rayet;mass-loss; evolution; fundamen- (WNL) stars in the LMC, based on new optical spectroscopy tal parameters – galaxies: Magellanic Clouds (AAT, MSO) and the Hillier (1990) atmospheric model. In a pre- vious paper (Crowther et al. 1995a), we showed that 4 out of the 10 known LMC Ofpe/WN9 stars should be re-classified WN9– 10. We now present observations of the remaining stars (except the LBV R127), and show that they are also WNL (WN9–11) 1. Introduction stars, with the exception of R99. Our total sample consists of 17 stars, and represents all but one of the single LMC WN6– Quantitative studies of hot luminous stars in galaxies are im- 11 population and allows a direct comparison with the stellar portant for a number of reasons. First, and probably foremost, parameters and chemical abundances of Galactic WNL stars is the information they provide on the effect of the environment (Crowther et al. 1995b; Hamann et al. 1995a). Previously un- on such fundamental properties as the mass-loss rate and stellar published ultraviolet (HST-FOS, IUE-HIRES) spectroscopy are evolution. In the standard picture (e.g. Maeder & Meynet 1987) presented for a subset of our programme stars. -

The Stellar Parameters of the SMC WR Binary HD 5980

Wolf-Rayet Phenomena in Massive Stars and Starburst Galaxies Proceedings [AU Symposium No. 193, @1999 [AU K.A. van der Hucht, G. Koenigsberger & P.R.J. Eenens, eds. The stellar parameters of the SMC WR binary HD 5980 Jorg Schweickhardt' and Werner Schmutz/ 1Landessternwarte Koniqstuhl, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany 2Institut fur Astronomie, ETH-Zentrum, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland Abstract. We present the temporal variation of the stellar parameters of the erupting star in HD 5980. We derive the effective temperature and radius from the observed changes of the visual magnitude. Our analysis is based on the assumption that the luminosity of the erupting star remained constant and that the brightness of the second star did not vary. 1. The determination of the stellar parameters T* and R* A simple method to derive the changes of the parameters T* and R* of a star is to analyze the variations of the visual magnitude My. Using Stefan-Boltzmann's law and the dependence of the observed flux, fA' on distance one gets oo 4 _ F Jo fAdA aT*- 1[' A fA . (1) Knowing the luminosity L ex Jooo fAdA and the visual magnitude My ex log fA' A == 5555 A, only the theoretical knowledge of the astrophysical flux FA emitted in the V band is needed to derive the temperature and the radius with equation (1). As a simple approximation we use here the Planck function BA(T*) for FA' If we want to apply this method to the binary system HD 5980, we need additional assumptions: (a) the LBV-like outburst in 1994 is the result of the eruption of only one star (star A, classified as an 071 star before eruption); (b) the luminosity of the erupting star remains constant with time; and (c) there is no variability of the companion (star B, WN 4). -

Wolf-Rayet Spin at Low Metallicity and Its Implication for Black Hole

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. vink-wr c ESO 2021 July 27, 2021 Wolf-Rayet spin at low metallicity and its implication for Black Hole formation channels Jorick S. Vink1, Tim J. Harries2 1 Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, Northern Ireland, UK 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4QL, UK Preprint online version: July 27, 2021 ABSTRACT Context. The spin of Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars at low metallicity (Z) is most relevant for our understanding of gravitational wave sources such as GW 150914, as well as the incidence of long-duration gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). Two scenarios have been suggested for both phenomena: one of them involves rapid rotation and quasi-chemical homogeneous evolution (CHE), the other invokes classical evolution through mass loss in single and binary systems. Aims. The stellar spin of Wolf-Rayet stars might enable us to test these two scenarios. In order to obtain empirical constraints on black hole progenitor spin we infer wind asymmetries in all 12 known WR stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) at Z = 1/5Z⊙, as well as within a significantly enlarged sample of single and binary WR stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC at Z = 1/2Z⊙), tripling the sample of Vink (2007). This brings the total LMC sample to 39, making it appropriate for comparison to the Galactic sample. Methods. We measure WR wind asymmetries with VLT-FORS linear spectropolarimetry, a tool uniquely poised to perform such tasks in extra- galactic environments. Results. We report the detection of new line effects in the LMC WN star BAT99-43 and the WC star BAT99-70, as well as the famous WR/LBV HD 5980 in the SMC, which might be evolving chemically homogeneously. -

The Electric Sun Hypothesis

Basics of astrophysics revisited. II. Mass- luminosity- rotation relation for F, A, B, O and WR class stars Edgars Alksnis [email protected] Small volume statistics show, that luminosity of bright stars is proportional to their angular momentums of rotation when certain relation between stellar mass and stellar rotation speed is reached. Cause should be outside of standard stellar model. Concept allows strengthen hypotheses of 1) fast rotation of Wolf-Rayet stars and 2) low mass central black hole of the Milky Way. Keywords: mass-luminosity relation, stellar rotation, Wolf-Rayet stars, stellar angular momentum, Sagittarius A* mass, Sagittarius A* luminosity. In previous work (Alksnis, 2017) we have shown, that in slow rotating stars stellar luminosity is proportional to spin angular momentum of the star. This allows us to see, that there in fact are no stars outside of “main sequence” within stellar classes G, K and M. METHOD We have analyzed possible connection between stellar luminosity and stellar angular momentum in samples of most known F, A, B, O and WR class stars (tables 1-5). Stellar equatorial rotation speed (vsini) was used as main parameter of stellar rotation when possible. Several diverse data for one star were averaged. Zero stellar rotation speed was considered as an error and corresponding star has been not included in sample. RESULTS 2 F class star Relative Relative Luminosity, Relative M*R *eq mass, M radius, L rotation, L R eq HATP-6 1.29 1.46 3.55 2.950 2.28 α UMi B 1.39 1.38 3.90 38.573 26.18 Alpha Fornacis 1.33 -

UV Spectroscopy of Massive Stars

galaxies Review UV Spectroscopy of Massive Stars D. John Hillier Department of Physics and Astronomy & Pittsburgh Particle Physics, Astrophysics and Cosmology Center (PITT PACC), University of Pittsburgh, 3941 O’Hara Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15260, USA; [email protected] Received: 11 July 2020; Accepted: 6 August 2020; Published: 12 August 2020 Abstract: We present a review of UV observations of massive stars and their analysis. We discuss O stars, luminous blue variables, and Wolf–Rayet stars. Because of their effective temperature, the UV (912 − 3200 Å) provides invaluable diagnostics not available at other wavebands. Enormous progress has been made in interpreting and analysing UV data, but much work remains. To facilitate the review, we provide a brief discussion on the structure of stellar winds, and on the different techniques used to model and interpret UV spectra. We discuss several important results that have arisen from UV studies including weak-wind stars and the importance of clumping and porosity. We also discuss errors in determining wind terminal velocities and mass-loss rates. Keywords: massive stars; O stars; Wolf–Rayet stars; UV; mass loss; stellar winds 1. Introduction According to Wien’s Law, the peak of a star’s energy distribution occurs in the UV for a star whose temperature exceeds 10,000 K. In practice, the temperature needs to exceed 10,000 K because of the presence of the Balmer jump. Temperatures greater than 10,000 K correspond to main-sequence stars of mass greater than ∼ 2 M and spectral types B9 and earlier. Early UV observations were made by rocket-flown instruments (e.g., [1,2]). -

Wolf-Rayet Spin at Low Metallicity and Its Implication for Black Hole Formation Channels Jorick S

A&A 603, A120 (2017) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201730503 & c ESO 2017 Astrophysics Wolf-Rayet spin at low metallicity and its implication for black hole formation channels Jorick S. Vink1 and Tim J. Harries2 1 Armagh Observatory and Planetarium, College Hill, Armagh BT61 9DG, Northern Ireland, UK e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4QL, UK Received 26 January 2017 / Accepted 28 March 2017 ABSTRACT Context. The spin of Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars at low metallicity (Z) is most relevant for our understanding of gravitational wave sources, such as GW 150914, and of the incidence of long-duration gamma-ray bursts (GRBs). Two scenarios have been suggested for both phenomena: one of them involves rapid rotation and quasi-chemical homogeneous evolution (CHE) and the other invokes classical evolution through mass loss in single and binary systems. Aims. The stellar spin of WR stars might enable us to test these two scenarios. In order to obtain empirical constraints on black hole progenitor spin we infer wind asymmetries in all 12 known WR stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC) at Z = 1=5 Z and within a significantly enlarged sample of single and binary WR stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC at Z = 1=2 Z ), thereby tripling the sample of Vink from 2007. This brings the total LMC sample to 39, making it appropriate for comparison to the Galactic sample. Methods. We measured WR wind asymmetries with VLT-FORS linear spectropolarimetry, a tool that is uniquely poised to perform such tasks in extragalactic environments. -

The Wolf-Rayet Eclipsing Binary Hd 5980 in the Small

THE WOLF-RAYET ECLIPSING BINARY HD 5980 IN THE SMALL MAGELLANIC CLOUD Jacques Breysacher European Southern Observatory, Garching bei Miinchen Anthony F. J. Moffat Departement de Physique, Universite de Montreal Virp i S. Niemela Instituto de Astronomia y Fisica del Espacio, and Instituto de Radioastronomia, Buenos Aires 1 . INTRODUCTION The Wolf-Rayet star HD 5980, which is probably associa ted with the bright HII region NGC 346 of the Small Magella nic Cloud, was found to be an eclipsing binary by Hoffmann, Stift and Moffat (1978). Breysacher and Perrier (1980) deter mined the orbital period, P=19.266±0.003d , of the system whose light curve reveals a strongly eccentric orbit (e=0.47 for i=80°). The behaviour of the light curve outside the eclipses shows that we are dealing with a rather complex bi nary system. An analysis of the spectroscopic data is pre sented here . 2. OBSERVATIONS AND RESULTS More than seventy spectra from two observatories are combined for the present study. 1)A series of 43 spectrograms (124 A°mm ) obtained during the period September 1975 - October 1978 by JB at the ESO 1.5m telescope on La Silla, Chile, with the "Echelec" spec- trograph (Baranne and Duchesne, 1976) equipped with a Lailemand-Duchesne "camera electronique". 2)A series of 28 spectrograms (45 A°mm~~') obtained by AFJM, VSN and R. Mendez from December 1978 to January 1980, using the Carnegie image tube attached to the spectrograph on the 1m Yale telescope on Cerro Tololo, Chile. 317 C. W. H. de Loore and A. J. Willis (eds.J, Wolf-Rayet Stars: Observations, Physics, Evolution, 317-320. -

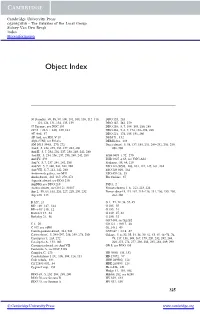

Object Index

Cambridge University Press 0521651816 - The Galaxies of the Local Group Sidney Van Den Bergh Index More information Object Index 30 Doradus, 49, 88, 99, 100, 101, 108, 110, 112–116, DDO 155, 263 121, 124, 131, 134, 135, 139 DDO 187, 263, 279 47 Tucanae, see NGC 104 DDO 210, 5, 7, 194–195, 280, 288 287.5 + 22.5 + 240, 139, 161 DDO 216, 5, 6, 7, 174, 192–194, 280 AE And, 37 DDO 221, 174, 188–191, 280 AF And, see M31 V 19 DEM 71, 132 Alpha UMi, see Polaris DEM L316, 133 AM 1013-394A, 270, 272 Draco dwarf, 5, 58, 137, 185, 231, 249–252, 256, 259, And I, 5, 234, 235, 236, 237, 242, 280 262, 280 And II, 5, 7, 234, 236, 237, 238, 240, 242, 280 And III, 5, 234, 236, 237, 238, 240, 242, 280 EGB 0419 + 72, 270 And IV, 234 EGB 0427 + 63, see UGC-A92 And V, 5, 7, 237–240, 242, 280 Eridanus, 58, 64, 229 And VI, 5, 7, 240, 241, 242, 280 ESO 121-SC03, 103, 104, 124, 125, 161, 162 And VII, 5, 7, 241, 242, 280 ESO 249-010, 264 Andromeda galaxy, see M31 ESO 439-26, 55 Antlia dwarf, 265–267, 270, 272 Eta Carinae, 37 Aquarius dwarf, see DDO 210 AqrDIG, see DDO 210 F8D1, 2 Arches cluster, see G0.121+0.017 Fornax clusters 1–6, 222, 223, 224 Arp 2, 58, 64, 161, 226, 227, 228, 230, 232 Fornax dwarf 5, 94, 167, 219–226, 231, 256, 259, 260, Arp 220, 113 262, 280 B 327, 24 G 1, 27, 32, 34, 35, 45 BD +40◦ 147, 164 G 105, 35 BD +40◦ 148, 12 G 185, 31 Berkeley 17, 54 G 219, 27, 32 Berkeley 21, 56 G 280, 32 G0.7-0.0, see Sgr B2 C1,20 G0.121 + 0.017, 48 C 107, see vdB0 G1.1-0.1, 49 Camelopardalis dwarf, 241, 242 G359.87 + 0.18, 67 Carina dwarf, 5, 245–247, 256, 259, -

Comprehensive Analyses of Massive Binaries and Implications on Stellar Evolution

Institut für Physik und Astronomie Astrophysik I Comprehensive analyses of massive binaries and implications on stellar evolution Kumulative Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades “doctor rerum naturalium” (Dr. rer. nat.) in der Wissenschaftsdisziplin Astrophysik eingereicht an der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Potsdam von Tomer Shenar Potsdam, den 02. September 2016 Published online at the Institutional Repository of the University of Potsdam: URN urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-104857 http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:kobv:517-opus4-104857 Abstract (English / Deutsch) Via their powerful radiation, stellar winds, and supernova explosions, massive stars (Mini & 8 M ) bear a tremendous impact on galactic evolution. It became clear in recent decades that the majority of massive stars reside in binary systems. This thesis sets as a goal to quantify the impact of binarity (i.e., the presence of a companion star) on massive stars. For this purpose, massive binary systems in the Local Group, including OB-type binaries, high mass X-ray binaries (HMXBs), and Wolf-Rayet (WR) binaries, were investigated by means of spectral, orbital, and evolutionary analyses. The spectral analyses were performed with the non-local thermodynamic equillibrium (non-LTE) Pots- dam Wolf-Rayet (PoWR) model atmosphere code. Thanks to critical updates in the calculation of the hydrostatic layers, the code became a state-of-the-art tool applicable for all types of hot massive stars (Chapter 2). The eclipsing OB-type triple system δ Ori served as an intriguing test-case for the new version of the PoWR code, and provided key insights regarding the formation of X-rays in massive stars (Chapter 3). -

An X-Ray Investigation of the NGC346 Field in the SMC (1): the LBV

An X-ray investigation of the NGC 346 field in the SMC (1) : the LBV HD 5980 and the NGC 346 cluster Y. Naz´e1,8, J.M. Hartwell2, I.R. Stevens2, M. F. Corcoran3, Y.-H. Chu4, G. Koenigsberger5, A.F.J. Moffat6, V.S. Niemela7 ABSTRACT We present results from a Chandra observation of the NGC 346 cluster. This cluster contains numerous massive stars and is responsible for the ionization of N66, the most luminous H ii region and the largest star formation region in the SMC. In this first paper, we will focus on the characteristics of the main objects of the field. The NGC 346 cluster itself shows only relatively unabs 34 −1 faint X-ray emission (with LX ∼ 1.5 × 10 erg s ), tightly correlated with the core of the cluster. In the field also lies HD 5980, a LBV star in a binary (or possibly a triple system) that is detected for the first time at X-ray energies. The star is X-ray bright, with an unabsorbed unabs 34 −1 luminosity of LX ∼ 1.7 × 10 erg s , but needs to be monitored further to investigate its X-ray variability over a complete 19 d orbital cycle. The high X-ray luminosity may be associated either with colliding winds in the binary system or with the 1994 eruption. HD 5980 is surrounded by a region of diffuse X-ray emission, which is a supernova remnant. While it may be only a chance alignment with HD 5980, such a spatial coincidence may indicate that the remnant is indeed related to this peculiar massive star.