CBA Evaluation Report-Final Version

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Executive

Comprehensive analysis EXECUTIVE of regional labour market and review of the State Employment Service activity in Zaporizhzhia SUMMARY Oblast Oksana Nezhyvenko PhD in Economics Individual Consultant EXECUTIVE SUMMARY - 2020 3 This executive summary is the result of the study of the labour market of Zaporizhzhia Oblast and the activities of the State Employment Service in Zaporizhzhia Oblast held during January-May 2020. The study was conducted within the United Nations Recovery and Peacebuilding Programme, which operates in six oblasts of Ukraine: Donetsk, Luhansk, Dnipropetrovsk, Zaporizhzhia and Kharkiv; the Rule of Law Prog- ram operates in Zhytomyr Oblast. This study was conducted within the framework of Economic Recovery and Restoration of Critical Infrastructure Component. FOLLOWING ACTIVITIES WERE CARRIED OUT AS PART OF THIS STUDY: — statistical data analysed to conduct comprehensive analysis of the labour market dynamics of Zaporizhzhia Oblast; — review of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast Employment Centre activities provided in terms of services and types of benefits it ensures to the unemployed and employers in the Oblast; — interviews with representatives of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast Employment Centre and employers of Zaporizhzhia Oblast on the local labour market conducted, description of these interviews provided; — survey of employers of Zaporizhzhia Oblast was conducted and responses were analysed; — forecast of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast labour market demand carried out. Executive summary is structured in accordance with the above points. The author of the study expresses her gratitude to the representatives of the State Employment Service, the Zaporizhzhia Oblast Employment Centre, district and city-district branches of the Zaporizhzhia Oblast Employment Centre, employers and experts who helped to collect the necessary information and complete the full pic- ture of the labour market of Zaporizhzhia Oblast to deliver it to the reader of this executive summary. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1992, No.26

www.ukrweekly.com Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc.ic, a, fraternal non-profit association! ramian V Vol. LX No. 26 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY0, JUNE 28, 1992 50 cents Orthodox Churches Kravchuk, Yeltsin conclude accord at Dagomys summit by Marta Kolomayets Underscoring their commitment to signed by the two presidents, as well as Kiev Press Bureau the development of the democratic their Supreme Council chairmen, Ivan announce union process, the two sides agreed they will Pliushch of Ukraine and Ruslan Khas- by Marta Kolomayets DAGOMYS, Russia - "The agree "build their relations as friendly states bulatov of Russia, and Ukrainian Prime Kiev Press Bureau ment in Dagomys marks a radical turn and will immediately start working out Minister Vitold Fokin and acting Rus KIEV — As The Weekly was going to in relations between two great states, a large-scale political agreements which sian Prime Minister Yegor Gaidar. press, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church change which must lead our relations to would reflect the new qualities of rela The Crimea, another difficult issue in faction led by Metropolitan Filaret and a full-fledged and equal inter-state tions between them." Ukrainian-Russian relations was offi the Ukrainian Autocephalous Ortho level," Ukrainian President Leonid But several political breakthroughs cially not on the agenda of the one-day dox Church, which is headed by Metro Kravchuk told a press conference after came at the one-day meeting held at this summit, but according to Mr. Khasbu- politan Antoniy of Sicheslav and the conclusion of the first Ukrainian- beach resort, where the Black Sea is an latov, the topic was discussed in various Pereyaslav in the absence of Mstyslav I, Russian summit in Dagomys, a resort inviting front yard and the Caucasus circles. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1994

1NS1DE: ^ voter turnout in repeat parliamentary elections - page 3. " Committee focuses on retrieving Ukraine's cultural treasures - page 3. o. ^ Mykhailo Chereshniovsky dead at 83 - page 5. THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-profit association vol. LXII No. 31 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY ЗІ , 1994 75 cents international Monetary Fund Repeat elections succeed in filling to assist Ukraine's recovery only 20 Parliament seats out of 112 by Marta Kolomayets Foreign Affairs. by Marta Kolomayets in Washington. Kyylv Press Bureau Sounding invigorated and optimistic, Kyyiv Press Bureau 9 Odessa region: Yuriy Kruk; deputy Mr. Camdessus said he was impressed minister of transportation. KYYiv - The international Monetary with the Ukrainian leadership and its KYYiv - Only 20 deputies were elect– 9 Kharkiv region: volodymyr Fund will work together with the Ukrainian commitment to reform. He said that Mr. ed on Sunday, July 24, in the latest round Semynozhenko, an academic and direc– of voting to fill 112 vacant seats in the 450- government to help this country recover Kuchma showed him a document outlin– tor of a research institute. from a sagging economy, said Michel seat Ukrainian Supreme Council, reported 9 ing key issues he wants to tackle to move Khmelnytsky region: viktor Camdessus, 1MF managing director, during the Central Electoral Commission. ahead with economic reform. Semenchuk, a director of a trading orga– a visit to Kyyiv on Wednesday, July 27. Commission officials said that many Although Mr. Kuchma has not yet dis– nization. "We have now a clear window of of the parliamentary races were unable to 9 opportunity for action. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions Kyiv, 27 October 2015

European Network of Election Європейська мережа організацій Monitoring Organizations зі спостереження за виборами International Observation Mission to Ukraine Міжнародна місія зі спостереження в Україні Local Elections 2015 Місцеві вибори 2015 Statement of Preliminary Findings and Conclusions Kyiv, 27 October 2015 The first round of Ukrainian local elections was mainly held in a peaceful environment and in line with most international standards and national legislation. However, the politicized composition and conduct of a number of territorial election commissions, supplemented with the complexity of the new law leave space for concern. The European Network of Election Monitoring Organizations (ENEMO) is a network of 22 leading election monitoring organizations from 18 countries of Europe and Central Asia, including three European Union countries. This is the tenth Election Observation Mission by ENEMO to Ukraine, which began with the arrival of 8 core team members to Kyiv, on 1 October in order to observe the Local Elections 2015. ENEMO additionally deployed 50 long-term observers (LTOs) countrywide to observe and assess the electoral process in their respective regions for the elections on 25 October 2015, as well as the eventual second round of elections. 180 short-term observers (STOs) have been deployed to observe the first round of elections to Ukraine. Together with mobile LTOs, ENEMO had 93 teams in the field, which have monitored the opening of 93 PECs, voting in 1211 PECs and the closing of 93 PECs. This preliminary report is based on the ENEMO observers’ findings from the field, where they focused on the work of election administration bodies, the conduct of election participants, the overall conduct of elections during Election day in terms of opening, voting, counting and the transferring of election materials, election-related complaints and appeals and other election related activities. -

SGGEE Ukrainian Gazetteer 201908 Other.Xlsx

SGGEE Ukrainian gazetteer other oblasts © 2019 Dr. Frank Stewner Page 1 of 37 27.08.2021 Menno Location according to the SGGEE guideline of October 2013 North East Russian name old Name today Abai-Kutschuk (SE in Slavne), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 454300 331430 Абаи-Кучук Славне Abakly (lost), Pervomaiske, Crimea, Ukraine 454703 340700 Абаклы - Ablesch/Deutsch Ablesch (Prudy), Sovjetskyi, Crimea, Ukraine 451420 344205 Аблеш Пруди Abuslar (Vodopiyne), Saky, Crimea, Ukraine 451837 334838 Абузлар Водопійне Adamsfeld/Dsheljal (Sjeverne), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 452742 333421 Джелял Сєверне m Adelsheim (Novopetrivka), Zaporizhzhia, Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine 480506 345814 Вольный Новопетрівка Adshiaska (Rybakivka), Mykolaiv, Mykolaiv, Ukraine 463737 312229 Аджияск Рибаківка Adshiketsch (Kharytonivka), Simferopol, Crimea, Ukraine 451226 340853 Аджикечь Харитонівка m Adshi-Mambet (lost), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 452227 341100 Аджи-мамбет - Adyk (lost), Leninske, Crimea, Ukraine 451200 354715 Адык - Afrikanowka/Schweigert (N of Afrykanivka), Lozivskyi, Kharkiv, Ukraine 485410 364729 Африкановка/Швейкерт Африканівка Agaj (Chekhove), Rozdolne, Crimea, Ukraine 453306 332446 Агай Чехове Agjar-Dsheren (Kotelnykove), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 452154 340202 Агьяр-Джерень Котелникове Aitugan-Deutsch (Polohy), Krasnohvardiiske, Crimea, Ukraine 451426 342338 Айтуган Немецкий Пологи Ajkaul (lost), Pervomaiske, Crimea, Ukraine 453444 334311 Айкаул - Akkerman (Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi), Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Odesa, Ukraine 461117 302039 Белгород-Днестровский -

QUARTERLY REPORT for the Development Initiative For

QUARTERLY REPORT for the Development Initiative for Advocating Local Governance in Ukraine (DIALOGUE) Project January - March 2013 QUARTERLY REPORT January - March 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS RESUME 5 Chapter 1. KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN THE REPORTING PERIOD 6 Chapter 2. PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION 10 2.1. Component 1: Legal Framework 10 Activity 2.1.1. Legislation drafting based on local governments legislative needs 10 Local government legislation need assessment 10 Technical Area Profiles 12 Legislation monitoring 14 Activity 2.1.2. Expert evaluation of conformity of draft legislation 21 to the European Charter of Local Self-Governance Activity 2.1.3. Introduction of institutional tools for local governments 22 to participate in legislation drafting Round table discussions in AUC Regional Offices and meetings of AUC Professional 22 Groups Setting up a network of lawyers to participate in legislation drafting 32 2.2. Component 2: Policy dialogue 33 Activity 2.2.1. Increasing the participation of the AUC member cities 33 in the policy dialogue established be the Association at the national level Dialogue Day at the Local Government Forum 33 Consultations on budget preparation 33 Cooperation with central government authorities 35 Parliamentary local government inter-faction group (local government caucus) 39 Participation in the work of parliamentary committees 39 Activity 2.2.2. Setting up advisory boards at the regional level with participation 41 of AUC Regional Offices and local State Executive agencies at the oblast level Setting up and working sessions of Local Government Regional Advisory Boards 41 Selection of issues to be discussed at working meetings of Local Government 47 Regional Advisory Boards in 2012-2013 Activity 2.2.3. -

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�1(127) January 2, 2013 Annoucements of conducting 000004 PJSC “DTEK Donetskoblenergo” procurement procedures 11 Lenina Ave., 84601 Horlivka, Donetsk Oblast Tryhub Viktor Anatoliiovych tel.: (0624) 57–81–10; 000002 Motor Roads Service in Chernihiv Oblast tel./fax: (0624) 57–81–15; of State Motor Roads Service of Ukraine e–mail: [email protected] 17 Kyivska St., 14005 Chernihiv Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Martynov Yurii Vasyliovych www.tender.me.gov.ua tel.: (0462) 69–95–55; Procurement subject: works on construction of cable section КПЛ 110 kV tel./fax: (0462) 65–12–60; “Azovska – Horod–11 No.1, 2” and cable settings on substation 220 kV e–mail: [email protected] “Azovska” Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Supply/execution: Separated Subdivision “Khartsyzk Electrical Networks” of the www.tender.me.gov.ua customer (Mariupol, Zhovtnevyi District, Donetsk Oblast), April – August 2013 Website which contains additional information on procurement: Procurement procedure: open tender www.ukravtodor.gov.ua Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 320 Procurement subject: code 63.21.2 – services of transport infrastructure for Submission: at the customer’s address, office 320 road transport (maintenance of principal and local motor roads in general 23.01.2013 12:00 use and artificial constructions on them in Chernihiv Oblast) Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office 320 Supply/execution: -

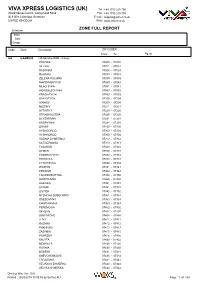

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA -

Facilitating Private Sector Participation in Delivery of Humanitarian Aid and Infrastructure Rehabilitation in the Housing Sector – Laying the Foundation for Ppps

PUBLIC PRIVATE PARTNERSHIP DEVELOPMENT PROGRAM Facilitating Private Sector Participation in Delivery of Humanitarian Aid and Infrastructure Rehabilitation in the Housing Sector – Laying the Foundation for PPPs Wolfgang Amann Final Draft, 28 July 2015 Prepared for FHI 360 USAID Public Private Partnership Development Program (P3DP) Assoc.Prof.Dr. Wolfgang Amann Vienna/Austria [email protected]; +43 650 301 69 60 with substantial contributions on legal questions by Nataly Dotsenko-Belous, Lawyer of Specstroymontazh Ukraina Ltd., Kharkiv. Acknowledgements to: the P3DP team with Mickey Mullay and Irina Davydova, Irina Bass for organization and competent translation, Nataly Dotsenko-Belous, Lawyer of Specstroymontazh Ukraina Ltd. Telman Abbasov, president FIABCI-Ukraine for great support in organizing meetings all over Ukraine, but particularly in Odessa, Yuriy Polushin, FIABCI-Ukraine for support in organizing meetings in Dnepropetrovsk, Andriy Pylypchuk, FIABCI-Ukraine for support in attending meetings in Kyiv. 2 CONTENTS A. ASSIGNMENT 4 A.1 P3DP and housing 4 A.2 Structure of the report 5 B. PRIVATE SECTOR PARTICIPATION IN ADRESSING IDP HOUSING SOLUTIONS 6 B.1 Situation of IDPs in Ukraine 6 B.2 Policies, mechanisms, and institutions for IDP housing 9 B.3 Existing social housing programs 10 B.4 Private sector social housing supply 12 B.5 Existing PPP legislation applicable on housing 12 B.6 PPP housing in other countries 13 B.7 Donor’s activities in IDP housing solutions 14 C. PRIVATE SECTOR HOUSING MODELS TARGETING IDPS 15 C.1 Model „Communal -

Important Plant Areas of Ukraine

Important Plant Areas of Ukraine Editor: V.A. Onyshchenko പ ˄ʪʶϱϬϮ͘ϳϱ;ϰϳϳͿ ʦϭϮ ^ĞůĞĐƟŽŶĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ Important Plant Areas of Ukraine / V.A. Onyshchenko (editor). – Kyiv: Alterpress, 2017. – 376 p. dŚĞŬĐŽŶƚĂŝŶƐĚĞƐĐƌŝƉƟŽŶƐŽĨϭϳϯ/ŵƉŽƌƚĂŶƚWůĂŶƚƌĞĂƐŽĨhŬƌĂŝŶĞ͘ĂƚĂŽŶĞĂĐŚƐŝƚĞ dŚĞĂŝŵŽĨƚŚĞ/ŵƉŽƌƚĂŶƚWůĂŶƚƌĞĂƐ;/WƐͿƉƌŽŐƌĂŵŵĞŝƐƚŽŝĚĞŶƟĨLJĂŶĚƉƌŽƚĞĐƚ ŝŶĐůƵĚĞŝƚƐĂƌĞĂ͕ŐĞŽŐƌĂƉŚŝĐĂůĐŽŽƌĚŝŶĂƚĞƐ͕ƐĞůĞĐƟŽŶĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ͕ĂƌĞĂƐŽĨhE/^ŚĂďŝƚĂƚƚLJƉĞƐ͕ ĂŶĞƚǁŽƌŬŽĨƚŚĞďĞƐƚƐŝƚĞƐĨŽƌƉůĂŶƚĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶƚŚƌŽƵŐŚŽƵƚƵƌŽƉĞĂŶĚƚŚĞƌĞƐƚŽĨƚŚĞ ĐŚĂƌĂĐƚĞƌŝnjĂƟŽŶŽĨǀĞŐĞƚĂƟŽŶ͕ƚŚƌĞĂƚƐ͕ŚƵŵĂŶĂĐƟǀŝƟĞƐ͕ŝŶĨŽƌŵĂƟŽŶĂďŽƵƚƉƌŽƚĞĐƚĞĚĂƌͲ ǁŽƌůĚ͕ ƵƐŝŶŐ ĐŽŶƐŝƐƚĞŶƚ ĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ ;ŶĚĞƌƐŽŶ͕ ϮϬϬϮͿ͘ dŚĞ ŝĚĞŶƟĮĐĂƟŽŶ ŽĨ /WƐ ŝƐ ďĂƐĞĚ ŽŶ ĞĂƐ͕ƌĞĨĞƌĞŶĐĞƐ͕ĂŶĚĂŵĂƉŽŶƚŚĞƐĂƩĞůŝƚĞŝŵĂŐĞďĂĐŬŐƌŽƵŶĚ͘ ƚŚƌĞĞĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂ͘ƌŝƚĞƌŝŽŶʹWƌĞƐĞŶĐĞŽĨƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚƉůĂŶƚƐƉĞĐŝĞƐ͗ƚŚĞƐŝƚĞŚŽůĚƐƐŝŐŶŝĮĐĂŶƚ ƉŽƉƵůĂƟŽŶƐŽĨŽŶĞŽƌŵŽƌĞƐƉĞĐŝĞƐƚŚĂƚĂƌĞŽĨŐůŽďĂůŽƌƌĞŐŝŽŶĂůĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶĐŽŶĐĞƌŶ͘ ʦ̸̨̛̙̣̞̯̦̞̦̞̌̏̍̌ ̨̛̯̖̬̯̬̞̟˄̡̛̬̟̦̌ͬ ̬̖̌̔̚͘ ʦ͘ʤ͘ ʽ̡̛̦̺̖̦̌͘ ʹ ʶ̛̟̏͗ ʤ̣̯̖̬̪̬̖̭͕̽ ƌŝƚĞƌŝŽŶʹWƌĞƐĞŶĐĞŽĨďŽƚĂŶŝĐĂůƌŝĐŚŶĞƐƐ͗ƚŚĞƐŝƚĞŚĂƐĂŶĞdžĐĞƉƟŽŶĂůůLJƌŝĐŚŇŽƌĂŝŶĂ ϮϬϭϳ͘ʹϯϳϲ̭͘ ƌĞŐŝŽŶĂůĐŽŶƚĞdžƚŝŶƌĞůĂƟŽŶƚŽŝƚƐďŝŽŐĞŽŐƌĂƉŚŝĐnjŽŶĞ͘ƌŝƚĞƌŝŽŶʹWƌĞƐĞŶĐĞŽĨƚŚƌĞĂƚĞŶĞĚ /^EϵϳϴͲϵϲϲͲϱϰϮͲϲϮϮͲϲ ŚĂďŝƚĂƚƐ͗ƚŚĞƐŝƚĞŝƐĂŶŽƵƚƐƚĂŶĚŝŶŐĞdžĂŵƉůĞŽĨĂŚĂďŝƚĂƚŽƌ ǀĞŐĞƚĂƟŽŶƚLJƉĞŽĨŐůŽďĂůŽƌ ʶ̛̦̐̌ ̛̥̞̭̯̯̽ ̨̛̛̪̭ ϭϳϯ ʦ̵̛̛̙̣̌̏ ̸̵̨̛̯̦̞̦̍̌ ̨̛̯̖̬̯̬̞̜ ˄̡̛̬̟̦̌͘ ʪ̦̞̌ ̨̪̬ ̡̨̙̦̱ ƌĞŐŝŽŶĂůƉůĂŶƚĐŽŶƐĞƌǀĂƟŽŶĂŶĚďŽƚĂŶŝĐĂůŝŵƉŽƌƚĂŶĐĞ͘Η/WΗŝƐŶŽƚĂŶŽĸĐŝĂůĚĞƐŝŐŶĂƟŽŶ͘ ̨̛̯̖̬̯̬̞̀ ̸̡̣̯̏̀̌̀̽ ̟̟ ̨̪̣̺̱͕ ̴̸̨̖̬̞̦̞̐̐̌ ̡̨̨̛̛̬̦̯͕̔̌ ̡̛̬̯̖̬̞̟ ̛̞̣̖̦̦͕̏̔́ ̨̪̣̺̞ /WƐĂƌĞƐĞůĞĐƚĞĚƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐĂůůLJƵƐŝŶŐĐƌŝƚĞƌŝĂƐƵƉƉŽƌƚĞĚďLJĞdžƉĞƌƚƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐũƵĚŐĞŵĞŶƚ͘ ̴̶̨̡̡̛̛̭̖̣̺̣̭̞̞̌̌̌̿̀̚hE/^̵̡̡̨̨̨̡̨̛̛̛̛̛̛͕̬̯̖̬̭̯̱̬̭̣̦̦̭̯̞͕̬͕̣̭̟̌̌̌̐̏̔̀̔̽̚̚ -

Through Times of Trouble Russian, Eurasian, and Eastern European Politics

i Through Times of Trouble Russian, Eurasian, and Eastern European Politics Series Editor: Michael O. Slobodchikoff, Troy University Mission Statement Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, little attention was paid to Russia, Eastern Europe, and the former Soviet Union. The United States and many Western governments reassigned their analysts to address different threats. Scholars began to focus much less on Russia, Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, instead turning their attention to East Asia among other regions. With the descent of Ukraine into civil war, scholars and govern- ments have lamented the fact that there are not enough scholars studying Russia, Eurasia, and Eastern Europe. This series focuses on the Russian, Eurasian, and Eastern European region. We invite contributions addressing problems related to the politics and relations in this region. This series is open to contributions from scholars representing comparative politics, international relations, history, literature, linguistics, religious studies, and other disciplines whose work involves this important region. Successful proposals will be acces- sible to a multidisciplinary audience, and advance our understanding of Russia, Eurasia, and Eastern Europe. Advisory Board Michael E. Aleprete, Jr Andrei Tsygankov Gregory Gleason Stephen K. Wegren Dmitry Gorenburg Christopher Ward Nicole Jackson Matthew Rojansky Richard Sakwa Books in the Series Understanding International Relations: Russia and the World, edited by Natalia Tsvetkova Geopolitical Prospects of the Russian Project of Eurasian Integration, by Natalya A. Vasilyeva and Maria L. Lagutina Eurasia 2.0: Russian Geopolitics in the Age of New Media, edited by Mark Bassin and Mikhail Suslov Executive Politics in Semi-Presidential Regimes: Power Distribution and Conflicts between Presidents and Prime Ministers, by Martin Carrier Post-Soviet Legacies and Conflicting Values in Europe: Generation Why, by Lena M.