Divine Mediators of Health Within Miami's Cuban-American Santeria Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P E E L C H R Is T Ian It Y , Is L a M , an D O R Isa R E Lig Io N

PEEL | CHRISTIANITY, ISLAM, AND ORISA RELIGION Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Christianity, Islam, and Orisa Religion THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF CHRISTIANITY Edited by Joel Robbins 1. Christian Moderns: Freedom and Fetish in the Mission Encounter, by Webb Keane 2. A Problem of Presence: Beyond Scripture in an African Church, by Matthew Engelke 3. Reason to Believe: Cultural Agency in Latin American Evangelicalism, by David Smilde 4. Chanting Down the New Jerusalem: Calypso, Christianity, and Capitalism in the Caribbean, by Francio Guadeloupe 5. In God’s Image: The Metaculture of Fijian Christianity, by Matt Tomlinson 6. Converting Words: Maya in the Age of the Cross, by William F. Hanks 7. City of God: Christian Citizenship in Postwar Guatemala, by Kevin O’Neill 8. Death in a Church of Life: Moral Passion during Botswana’s Time of AIDS, by Frederick Klaits 9. Eastern Christians in Anthropological Perspective, edited by Chris Hann and Hermann Goltz 10. Studying Global Pentecostalism: Theories and Methods, by Allan Anderson, Michael Bergunder, Andre Droogers, and Cornelis van der Laan 11. Holy Hustlers, Schism, and Prophecy: Apostolic Reformation in Botswana, by Richard Werbner 12. Moral Ambition: Mobilization and Social Outreach in Evangelical Megachurches, by Omri Elisha 13. Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity, by Pamela E. -

Santería in a Globalized World: a Study in Afro-Cuban Folkloric Music" (2018)

Lawrence University Lux Lawrence University Honors Projects 5-30-2018 Santería in a Globalized World: A Study in Afro- Cuban Folkloric Music Nathan Montgomery Lawrence University Follow this and additional works at: https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp Part of the African History Commons, Caribbean Languages and Societies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Latin American History Commons, Music Education Commons, Music Practice Commons, Oral History Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons © Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Recommended Citation Montgomery, Nathan, "Santería in a Globalized World: A Study in Afro-Cuban Folkloric Music" (2018). Lawrence University Honors Projects. 123. https://lux.lawrence.edu/luhp/123 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by Lux. It has been accepted for inclusion in Lawrence University Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Lux. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nathan Montgomery 4/30/18 IHRTLUHC SANTERÍA IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD: A STUDY OF AFRO-CUBAN FOLKLORIC MUSIC ABSTRACT The Yoruban people of modern-day Nigeria worship many deities called orichas by means of singing, drumming, and dancing. Their aurally preserved artistic traditions are intrinsically connected to both religious ceremony and eVeryday life. These forms of worship traVeled to the Americas during the colonial era through the brutal transatlantic slaVe trade and continued to eVolVe beneath racist societal hierarchies implemented by western European nations. Despite severe oppression, Yoruban slaves in Cuba were able to disguise orichas behind Catholic saints so that they could still actiVely worship in public. This initial guise led to a synthesis of religious practice, language, and artistry that is known today as Santería. -

Scenes and Impressions Abroad

SCENES IMPRESSIONS ABROAD. E Y THE REV. J. E. ROCKWELL, D.D. NEW YORK: ROBERT CARTER & BROTHERS No. 580 BROADWAY. 1860. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1860, by ROBERT CARTER AND BROTHERS, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of New York, EDWARD O. JENKINS, Printer # &tcrfotgper, No. 26 Frankfort Strket. ^s Sng*T>y -^-K. Biis/iia - fast^J ^.^T^tc^U^ TO MY WIFE, WHOSE SOCIETY WAS THE CHAEM WHICH MADE THESE SCENES- DELIGHTFUL AND MEMORABLE; TO MY PARENTS, WHOSE IN8TKUCTIONS AND COUNSELS HAVE EVER BEEN WISE, FAITHFUL AND SAFE; TO THE CENTRAL PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH OF BROOKLYN, WHOSE SYMPATHY AND EARNEST CO-OPERATION HAVE MADE MY WORK AS A PASTOR PLEASANT; THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED WITH EVERY FEELING OF RESPECT AND AFFECTION BY THE AUTHOR. SCENES AND IMPRESSIONS ABROAD, PREFACE, The substance of these Scenes and Impres- sions Abroad was presented in the form of a Series of Lectures, before the congregation to which it is my pleasure to minister, without a thought of giving to them any farther pub- licity. Unexpectedly they enlisted such atten- tion and apparent interest, as that it became necessary to adjourn from my Lecture Koom, where they were commenced, to the main Auditory of the Church, which place was filled every Wednesday evening for three months. Most of the Lectures were very fully reported in the columns of the Transcript, of this city, with kind and courteous notices of the course. At the request of many who heard them, or who had read the reports of them, and in Vlll PREFACE. -

As an Expression of Yorùbá Aesthetic Philosophy

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Vol 9 No 4 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Social Sciences July 2018 Research Article © 2018 Ajíbóyè et.al.. This is an open access article licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/). Orí (Head) as an Expression of Yorùbá Aesthetic Philosophy Olusegun Ajíbóyè Stephen Fọlárànmí Nanashaitu Umoru-Ọ̀ kẹ Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Obafemi Awólọ́ wọ University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria Doi: 10.2478/mjss-2018-0115 Abstract Aesthetics was never a subject or a separate philosophy in the traditional philosophies of black Africa. This is however not a justification to conclude that it is nonexistent. Indeed, aesthetics is a day to day affair among Africans. There are criteria for aesthetic judgment among African societies which vary from one society to the other. The Yorùbá of Southwestern Nigeria are not different. This study sets out to examine how the Yorùbá make their aesthetic judgments and demonstrate their aesthetic philosophy in decorating their orí, which means head among the Yorùbá. The head receives special aesthetic attention because of its spiritual and biological importance. It is an expression of the practicalities of Yorùbá aesthetic values. Literature and field work has been of paramount aid to this study. The study uses photographs, works of art and visual illustrations to show the various ways the head is adorned and cared for among the Yoruba. It relied on Yoruba art and language as a tool of investigating the concept of ori and aesthetics. Yorùbá aesthetic values are practically demonstrable and deeply located in the Yorùbá societal, moral and ethical idealisms. -

Roger Atwood Searching for a Head in Nigeria

roger atwood Searching for a Head in Nigeria A century ago, a German colonialist went to Nigeria and found a bronze masterpiece. Then, it vanished. Nigerians have been asking themselves what happened to it ever since. Now they may have the answer. A place of “lofty trees . as beautiful as Paradise.” So the German adventurer Leo Frobenius described the sacred Olokun Grove in Ife in 1910. For months before I arrived in Nigeria, I wondered what the grove would look like. Now I was riding in a car to see the grove with a delegation of curators and archaeologists from the Ife museum. They had a certain ceremoni- ousness I had come to expect from educated Nigerians, and they were snappy dressers. While I sweated through my khakis and linen shirt, the women in the delegation wore flowered dresses and matching head- dresses, and they curtsied deeply and held out their hand coquettishly when we were introduced. The men called me “sir” and wore tailored robes with a matching cap, or immaculately ironed Western trousers and a pressed shirt and never a T-shirt or, God forbid, shorts. The Olokun Grove was on Irebami Street, near Line 3. It was a neighborhood of rut- ted streets and ramshackle houses, some with posters on their walls ad- vertising Nollywood movies or displaying President Goodluck Jonathan’s jowly face grafted onto the emerald bands of the national flag. In three weeks’ time, the people of Africa’s most populous country would vote in presidential elections. Not my concern. I was going to see a place as beautiful as Paradise. -

African Concepts of Energy and Their Manifestations Through Art

AFRICAN CONCEPTS OF ENERGY AND THEIR MANIFESTATIONS THROUGH ART A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Renée B. Waite August, 2016 Thesis written by Renée B. Waite B.A., Ohio University, 2012 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ____________________________________________________ Fred Smith, Ph.D., Advisor ____________________________________________________ Michael Loderstedt, M.F.A., Interim Director, School of Art ____________________________________________________ John R. Crawford-Spinelli, D.Ed., Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES………………………………………….. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS …………………………………… vi CHAPTERS I. Introduction ………………………………………………… 1 II. Terms and Art ……………………………………………... 4 III. Myths of Origin …………………………………………. 11 IV. Social Structure …………………………………………. 20 V. Divination Arts …………………………………………... 30 VI. Women as Vessels of Energy …………………………… 42 VII. Conclusion ……………………………………….…...... 56 VIII. Images ………………………………………………… 60 IX. Bibliography …………………………………………….. 84 X. Further Reading ………………………………………….. 86 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1: Porogun Quarter, Ijebu-Ode, Nigeria, 1992, Photograph by John Pemberton III http://africa.si.edu/exhibits/cosmos/models.html. ……………………………………… 60 Figure 2: Yoruba Ifa Divination Tapper (Iroke Ifa) Nigeria; Ivory. 12in, Baltimore Museum of Art http://www.artbma.org/. ……………………………………………… 61 Figure 3.; Yoruba Opon Ifa (Divination Tray), Nigerian; carved wood 3/4 x 12 7/8 x 16 in. Smith College Museum of Art, http://www.smith.edu/artmuseum/. ………………….. 62 Figure 4. Ifa Divination Vessel; Female Caryatid (Agere Ifa); Ivory, wood or coconut shell inlay. Nigeria, Guinea Coast The Metropolitan Museum of Art, http://www.metmuseum.org. ……………………… 63 Figure 5. Beaded Crown of a Yoruba King. Nigerian; L.15 (crown), L.15 (fringe) in. -

Santería: from Slavery to Slavery

Santería: From Slavery to Slavery Kent Philpott This, my second essay on Santería, is necessitated for two reasons. One, requests came in for more information about the religion; and two, responses to the first essay indicated strong disagreement with my views. I will admit that my exposure to Santería,1 at that point, was not as thorough as was needed. Now, however, I am relying on a number of books about the religion, all written by decided proponents, plus personal discussions with a broad spectrum of people. In addition, I have had more time to process what I learned about Santería as I interacted with the following sources: (1) Santería the Religion,by Migene Gonzalez-Wippler, (2) Santería: African Spirits in America,by Joseph M. Murphy, (3) Santería: The Beliefs and Rituals of a Growing Religion in America, by Miguel A. De La Torre, (4) Yoruba-Speaking Peoples, by A. B. Ellis, (5) Kingdoms of the Yoruba, 3rd ed., by Robert S. Smith, (6) The Good The Bad and The Beautiful: Discourse about Values in Yoruba Culture, by Barry Hallen, and (7) many articles that came up in a Google search on the term "Santería,” from varying points of view. My title for the essay, "From Slavery to Slavery," did not come easily. I hope to be as accepting and tolerant of other belief systems as I can be. However, the conviction I retained after my research was one I knew would not be appreciated by those who identified with Santería. Santería promises its adherents freedom but succeeds only in bringing them into a kind of spiritual, emotional, and mental bondage that is as devastating as the slavery that originally brought West Africans to the New World in the first place. -

The Winter's Tale Study Guide Table of Contents Summary

The Winter's Tale Study Guide Table of Contents Summary..............................................................................................................................................................1 Biography.............................................................................................................................................................4 Themes.................................................................................................................................................................6 Characters...........................................................................................................................................................9 Critical Essays...................................................................................................................................................13 Analysis............................................................................................................................................................891 Quotes...............................................................................................................................................................896 i Summary Summary Polixenes, the king of Bohemia, is the guest of Leontes, the king of Sicilia. The two men were friends since boyhood, and there is much celebrating and joyousness during the visit. At last Polixenes decides that he must return to his home country. Leontes urges him to extend his visit, but Polixenes refuses, saying that -

ALAIANDÊ Xirê DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO

ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO ALAIANDÊ XirÊ DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO ALAIANDÊ XIRÊ DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI ORGANIZAÇÃO VAGNER GONÇALVES DA SILVA ROSENILTON SILVA DE OLIVEIRA JOSÉ PEDRO DA SILVA NETO DOI: 10.11606/9786550130060 ALAIANDÊ XIRÊ DESAFIOS DA CULTURA RELIGIOSA AFRO-AMERICANA NO SÉCULO XXI São Paulo 2019 Os autores autorizam a reprodução e divulgação total ou parcial deste trabalho, por qualquer meio convencional ou eletrônico, para fns de estudo e pesquisa, desde que citada a fonte. Universidade de São Paulo Reitor: Vahan Agopyan Vice-reitor: Antonio Carlos Hernandes Faculdade de Educação Diretor: Prof. Dr. Marcos Garcia Neira Vice-Diretor: Prof. Dr. Vinicio de Macedo Santos Direitos desta edição reservados à FEUSP Avenida da Universidade, 308 Cidade Universitária – Butantã 05508-040 – São Paulo – Brasil (11) 3091-2360 e-mail: [email protected] http://www4.fe.usp.br/ Catalogação na Publicação Serviço de Biblioteca e Documentação Faculdade de Educação da Universidade de São Paulo A316 Alaiandê Xirê: desafos da cultura religiosa afro-americana no Século XXI / Vagner Gonçalves da Silva, Rosenilton Silva de Oliveira, José Pedro da Silva Neto (Organizadores). São Paulo: FEUSP, 2019. 382 p. Vários autores ISBN: 978-65-5013-006-0 (E-book) DOI: 10.11606/9786550130060 1. Candomblé. 2. Cultura afro. 3. Religião. 4. Religiões africanas. I. Silva, Vagner Gonçalves da. II. Oliveira, Rosenilton Silva de. III. Silva Neto, José Pedro. IV. Título. -

How I See the Yoruba See Themselves

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 5 Issue 1 Fall 1978 Article 3 1978 How I See the Yoruba See Themselves Stephen Sprague Recommended Citation Sprague, S. (1978). How I See the Yoruba See Themselves. 5 (1), 9-29. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol5/iss1/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol5/iss1/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. How I See the Yoruba See Themselves This contents is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol5/iss1/3 When I photographed in Nigeria, I mostly used a medium format camera and often a tripod. I always obtained the subject's permission and cooperation before photographing and invariably framed the sub ject straight-on. This turned out to be the way the HOW I SEE THE YORUBA Yoruba expected a good photographer to work, so I SEE THEMSELVES was immediately accorded respect among the Yoruba photographers and in the community, and I was se~ dom refused permission to photograph. I know that 1f I had been making candid photographs with a small STEPHEN SPRAGUE camera I would have met with a great deal of suspi cion and little understanding or respect. Though our manner of working may be similar, my Photographers and photographic studios are preva photographs are obviously quite different from those lent throughout many areas of Africa today, and par taken by Yoruba photographers. While photograph ticularly in West Africa many indigenous societies ing, I tried to be conscious of my own training in the make use of photography. -

STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA Grace Presbyterian Church Library; 7:00Pm; Tuesday, November 17, 2015

STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA Grace Presbyterian Church Library; 7:00pm; Tuesday, November 17, 2015 CALL TO ORDER AND OPENING PRAYER – The Rev. Trey Little CLERK’S REPORT & ADMINISTRATIVE MATTERS – David Finck, Clerk of Session • Consent Agenda MODERATOR’S REPORT – The Rev. Trey Little • Examination of Class of 2018 Church Officers • Election of Ruling Elder Commissioners for ECO National Meeting (January 26 – 28, 2016) • Facilities Improvement Team Update • ECO Discipleship Pilot Phase Update • Resolution to Dissolve Pastor Nominating Committee • Calling of a Congregational Meeting on Sunday, January 10, for the Purposes of: o Electing Class of 2018 Deacons and Trustees o Electing Church Officer Nominating Committee o Electing Grace Endowment Fund Trustees COMMITTEE REPORTS: ADMINISTRATION & FINANCE GRACE SCHOOL • See written report attached • No written report provided • Pastors’ Compensation MARRIED LIFE ADULT & JOY • No written report provided • See written report attached MISSIONS CONGREGATIONAL CARE • See written report attached • See written report attached WORSHIP EVANGELISM • See written report attached • See written report attached YOUNG ADULT & COLLEGE FAMILY • See written report attached • See written report attached CLOSING PRAYER NEXT SESSION MEETING: Tuesday, January 19 STATED SESSION MEETING AGENDA – November 17, 2015 Grace Presbyterian Church Session Business Meeting CONSENT AGENDA Tuesday, November 17, 2015 § Approve Minutes of the October 20, 2015 stated Session meeting. § Approve Minutes of the November 1, 2015 called -

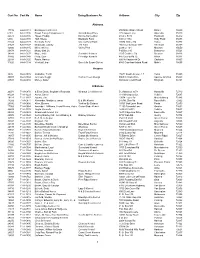

Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip 1 Cust No

Cust No Cert No Name Doing Business As Address City Zip Alabama 17732 64-A-0118 Barking Acres Kennel 250 Naftel Ramer Road Ramer 36069 6181 64-A-0136 Brown Family Enterprises Llc Grandbabies Place 125 Aspen Lane Odenville 35120 22373 64-A-0146 Hayes, Freddy Kanine Konnection 6160 C R 19 Piedmont 36272 6394 64-A-0138 Huff, Shelia Blackjack Farm 630 Cr 1754 Holly Pond 35083 22343 64-A-0128 Kennedy, Terry Creeks Bend Farm 29874 Mckee Rd Toney 35773 21527 64-A-0127 Mcdonald, Johnny J M Farm 166 County Road 1073 Vinemont 35179 42800 64-A-0145 Miller, Shirley Valley Pets 2338 Cr 164 Moulton 35650 20878 64-A-0121 Mossy Oak Llc P O Box 310 Bessemer 35021 34248 64-A-0137 Moye, Anita Sunshine Kennels 1515 Crabtree Rd Brewton 36426 37802 64-A-0140 Portz, Stan Pineridge Kennels 445 County Rd 72 Ariton 36311 22398 64-A-0125 Rawls, Harvey 600 Hollingsworth Dr Gadsden 35905 31826 64-A-0134 Verstuyft, Inge Sweet As Sugar Gliders 4580 Copeland Island Road Mobile 36695 Arizona 3826 86-A-0076 Al-Saihati, Terrill 15672 South Avenue 1 E Yuma 85365 36807 86-A-0082 Johnson, Peggi Cactus Creek Design 5065 N. Main Drive Apache Junction 85220 23591 86-A-0080 Morley, Arden 860 Quail Crest Road Kingman 86401 Arkansas 20074 71-A-0870 & Ellen Davis, Stephanie Reynolds Wharton Creek Kennel 512 Madison 3373 Huntsville 72740 43224 71-A-1229 Aaron, Cheryl 118 Windspeak Ln. Yellville 72687 19128 71-A-1187 Adams, Jim 13034 Laure Rd Mountainburg 72946 14282 71-A-0871 Alexander, Marilyn & James B & M's Kennel 245 Mt.