Forget That. Adopt One Instead. ‘Luther,’ by Ethan Lipton, at Here Arts Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feast Your Famine

Feast Your Famine: a watch-and-play is an interactive five-night performance-and-social-action hybrid event, re-envisioning the legacy of the "hero" in Western culture from medieval knights to today and seeking to practice new realities in community. With possibilities for multi-day game play or a single night's experience, audiences can join a diverse body of artists and activists in a journey of boundary crossing, soul-troubling, and action through both avant garde and traditional performances and social-action events -- set inside the framework of a re-imagined medieval feast. For details on the schedule and the presenters, please visit the Feast Your Famine website and follow the event on Instagram @feastyourfamine. This event is a result of Wistaria Project's Re-Residency, in which we "re-gift" the Performing Artist Residency we received from The Center at West Park to an exciting diversity of performers and activists. Each Re-Resident will present their work on one night of the festival. The Re-Resident Cohort has worked together to devise First Night and Last Night -- the opening and closing of the feast -- with interactive, hybrid performance/events to bring us together to imagine, engage, and take action here and now. Wednesday, November 13. FIRST NIGHT An interactive event inside a re-invented, justice-oriented medieval “feast”, created by the Re-Residents. Songs. Poetry. Activities. Quests. Re-Residents Mz Aza Metric Eric Farber Dhira Rausch Hee Ran Lee Jace Valentine (IntegrateNYC) Kelsey Pyro Monica Carillo Timothy Craig Wistaria Project Zafi Dimitropoulou Liquid Courage written by Kevin Green (Black Revolutionary Theater Workshop) Kevin Green is a Brooklyn-based actor/writer/producer. -

Encorethe Performing Arts Magazine Altria 2006 ~ Ext Wa \Le Eesllilal

October 2006 2006 Next Wave Festival *~ ...."""......,...<... McDermott & McGough, THIS IS ONE OF OUR FAVORITE PAINTINGS, 1936/2005 BAM 2006 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by: ENCOREThe Performing Arts Magazine Altria 2006 ~ ext Wa \Le EeslliLaL Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman William I. Campbell Chairman of the Board Vice Chairman of the Board Karen Brooks Hopkins Joseph V. Melillo President Executive Producer presents Mycenaean Written and directed by Carl Hancock Rux Approximate BAM Harvey Theater running time: Oct 10, 12-14, 2006 at 7:30pm one hour and 30 minutes, Writer/director/music Carl Hancock Rux no intermission Lighting/sound design, co-video design Pablo N. Molina Co-video design, music, programming Jaco van Schalkwyk Mask design, co-scenic design Alison Heimstead Co-scenic design Efren Delgadillo Jr. Costume coordination Toni-Leslie James Dramaturgy Morgan Jeness BAM 2006 Next Wave Festival is sponsored by Altria Group, Inc. Music programming at BAM is made possible by a generous grant from The New York State Music Fund, established by the New York State Attorney General at Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. Leadership support for BAM Theater is provided by The Shubert Foundation, Inc., with major support from SHS Foundation, Francena T. Harrison Foundation Trust, Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; and additional support from Billy Rose Foundation, Inc. Mycenaeaol..--- _ Cast Carl Hancock Rux Racine/Hippolytus Helga Davis Arachne Patrice Johnson Aricia Tony Torn Daedalus David Barlow Video Documentarian Ana Perea Dream Theorist Darius Mannino Dreamer/Soldier/Phillippe Celia Gorman Dreamer/Naiad/Nathalie Christalyn Wright Dreamer/Naiad Marcelle Lashley Dreamer/NaiadlWoman Niles Ford Dreamer/Soldier/ Minotaur Paz Tanjuaquio Dreamer/Naiad Kelly Bartnik Dreamer/Naiad Production Producer Carl Hancock Rux Executive Producers Stephen M. -

News of the Strange

Target Margin Theater 232 52nd Street Brooklyn, NY 11220 718-398-3095 Targetmargin.org @targetmargin Founding Artistic Director: David Herskovits Associate Artistic Director: Moe Yousuf General Manager: Liz English Space Manager: Kelly Lamanna Arts Management Fellow: Frank Nicholas Poon Box Office Manager: Lorna I. Pérez Financial Consultants: Michael Levinton, Patty Taylor Graphic Designer: Maggie Hoffman Interns: Sarah McEneaney, Matt Hunter Press Representation: John Wyszniewski/Everyman Agency BOARD OF DIRECTORS NEWS OF THE Hilary Alger, Matt Boyer, David Herskovits, Dana Kirchman, Kate Levin, Matt McFarlane, Jennifer Nadeau, Adam Weinstein, Amy Wilson. STRANGE LAB ABOUT US Target Margin is an OBIE Award-winning theater company that creates innovative productions of classic plays, and new plays inspired by history, literature, and other art forms. In our new home in Sunset Park we energetically expand the possibilities of live performance, and engage our community at all levels through partnerships and programs. TMT PROGRAMS INSTITUTE The Institute is a year-long fellowship (January – December) that provides five diverse artists space, support and a $1,000 stipend to challenge themselves and their art-making practice. 2019 Fellows: Sarah Dahnke, Mashuq Mushtaq Deen, Yoni Oppenheim, Gabrielle Revlock, and Sarah K. Williams. ARTISTS-IN-RESIDENCE The Artist Residency Program provides established, mid-career and emerging artists up to 100 hours of dedicated rehearsal and developmental space. Each residency is shaped to meet the specific needs of each artist and will include a work-in-progress free to the public. 2019 Artists-in-Residence: Tanisha Christie, Jesse Freedman, Sugar Vendil, Deepali Gupta, Sarah Hughes, and Chana Porter. SPACE RENTALS THE DOXSEE THEATER Our SPACE program provides long term / short term studio nd space for all artists to gather and engage in their creative / 232 52 Street, BK 11220 cultural practices. -

View the Program!

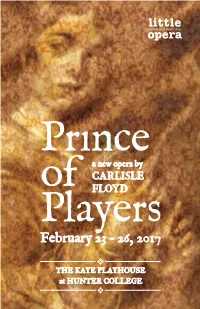

cast EDWARD KYNASTON Michael Kelly v Shea Owens 1 THOMAS BETTERTON Ron Loyd v Matthew Curran 1 VILLIERS, DUKE OF BUCKINGHAM Bray Wilkins v John Kaneklides 1 MARGARET HUGHES Maeve Höglund v Jessica Sandidge 1 LADY MERESVALE Elizabeth Pojanowski v Hilary Ginther 1 about the opera MISS FRAYNE Heather Hill v Michelle Trovato 1 SIR CHARLES SEDLEY Raùl Melo v Set in Restoration England during the time of King Charles II, Prince of Neal Harrelson 1 Players follows the story of Edward Kynaston, a Shakespearean actor famous v for his performances of the female roles in the Bard’s plays. Kynaston is a CHARLES II Marc Schreiner 1 member of the Duke’s theater, which is run by the actor-manager Thomas Nicholas Simpson Betterton. The opera begins with a performance of the play Othello. All of NELL GWYNN Sharin Apostolou v London society is in attendance, including the King and his mistress, Nell Angela Mannino 1 Gwynn. After the performance, the players receive important guests in their HYDE Daniel Klein dressing room, some bearing private invitations. Margaret Hughes, Kynaston’s MALE EMILIA Oswaldo Iraheta dresser, observes the comings and goings of the others, silently yearning for her FEMALE EMILIA Sahoko Sato Timpone own chance to appear on the stage. Following another performance at the theater, it is revealed that Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, has long been one STAGE HAND Kyle Guglielmo of Kynaston’s most ardent fans and admirers. SAMUEL PEPYS Hunter Hoffman In a gathering in Whitehall Palace, Margaret is presented at court by her with Robert Balonek & Elizabeth Novella relation Sir Charles Sedley. -

Elevator Repair Service

ELEVATOR REPAIR SERVICE ABRONS ARTS CENTER A CONVERSATION BETWEEN JOHN COLLINS AND KATE SCELSA Kate Scelsa: So, John! John Collins: Kate, you’ve worked as a company member with ERS for about sixteen years now…And it turns out that you were doing stealth research for all these years on what would be perfect parts to write for some of our actors. KS: This is going to sound very sentimental, but writing this play has really felt like a love letter to this company. So it’s that, combined with my very deep love for Edward Albee’s play and specifically for the character of Martha. JC: And it’s exciting for me because I’m getting to work with one of my favorite novelists, who wrote one of my favorite books of the past couple of years. KS: Thank you for that plug. JC: It also fits in really nicely with the shows you’ve worked on with us, taking another work of great American literature as a jumping off point. And looking at the parts you’ve played in ERS shows, there have been a lot of Marthas in your life. KS: I’ve always been very interested in whether or not embodying that kind of female rage could be seen as sympathetic. Even powerful. Or if those women just become the shrew. Which means their rage can be dismissed. JC: Well you take Martha, who’s an extreme character… KS: She doesn’t care what anyone thinks of her. But what are the consequences of that attitude? For most of Albee’s play we see Martha as this incredible feminist character, in that she and her husband are on equal footing, and that’s what makes it so fascinating to watch, and fun to play. -

Annual Report

EMPOWERING NEW YORK CITY GIRLS THROUGH THE ARTS ANNUAL REPORT SEPTEMBER 2014 — AUGUST 2015 vI E ANNUAL rEPOrT IDE SEPTEMBER 2014 — AUGUST 2015 INS DearAs you look viBeback on our Community, 2014-2015 fiscal year, I hope you will enjoy PROGRAMS reflecting on all of the progress viBe Theater Experience has made over these last twelve months. We are very proud to have served our girls through our unique and comprehensive programming 3-4 that provides them with the nurturing necessary to help them findB their individual voices and then courageously share those stories with all of us. VIBE GIRLS When I took the seat of Board Chair in September, my goal was to SPEAK build viBe’s internal capacity so that we are positioned to leverage all of our resources – human and fiscal – to best serve our girls. To that end, we welcomed new board members who have brought critical 5 professional and administrative skills to our governing efforts. We also brought in new volunteers to the viBenefit Committee who worked tirelessly to ensure that our annual fundraiser was once again a huge success. Finally, we instituted a new SPECIAL membership model designed to increase support and encourage our donors to stay EVENTS engaged with our work. As we enter into the 2015-2016 fiscal year, we look forward to continuing to provide meaningful and transformative opportunities for our viBe girls. As Chair, I also look forward 5-6 to building on the Board’s efforts; truly a “working board,” we will continue to strategically align our committee work to support and grow our fundraising and programming efforts. -

BY ROBIN FROHARDT Wednesday, June 30 - Sunday, July 11, 2021 661 Imperial Street ART MATTERS NOW MORE THAN EVER

Photo by Maria Baranova BY ROBIN FROHARDT Wednesday, June 30 - Sunday, July 11, 2021 661 Imperial Street ART MATTERS NOW MORE THAN EVER WELCOME TO UCLA’S CENTER FOR THE ART OF PERFORMANCE UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) is the public facing research and presenting organization for the performing arts at the University of California, Los Angeles—one of the world’s leading public research universities. We are housed within the UCLA School of the Arts & Architecture along with the Hammer and Fowler museums. The central pursuit of our work as an organization is to sustain the diversity of contemporary performing artists while celebrating their contributions to culture. We acknowledge, amplify and support artists through major presentations, commissions and creative development initiatives. Our programs offer audiences a direct connection to the ideas, perspectives and concerns of living artists. Through the lens of dance, theater, music, literary arts, digital media arts and collaborative disciplines, informed by diverse racial and cultural backgrounds, artists and audiences come together in our theaters and public spaces to explore new ways of seeing that expands our understanding of the world we live in now. cap.ucla.edu #CAPUCLA Photo by Tony Lewis CAP UCLA Presents BY ROBIN FROHARDT Wednesday, June 30 - Sunday, July 11, 2021 661 Imperial Street (DTLA) One store, two ways to experince, hundreds of bags Installation: (Duration 30 mins.) Tue-Fri 2:30PM-5PM (last entry 4:30 PM) Sat & Sun 12:30PM-2PM (last entry 1:30 PM) July 4: Closed July 5: Special hours 12PM-7PM (last entry 6:30 PM) Immersive Film Experience: (Duration 60 mins.) Tue-Fri 1PM & 6PM Sat & Sun 11AM, 3PM & 5PM July 4: Closed Recommended for Ages 12+ due to current health protocols MESSAGE FROM THE ARTIST Dear Most Valued Customers: It’s almost impossible for me to try to explain what it is you are about to experience and the journey it took to get here. -

When Pipsy, a Pedigree Cocker Spaniel, Lands at Bitchfield Animal Shelter, She Becomes the Center of a Turf War Between Dogs & Cats

LOCKED UP BITCHES by catya mcmullen featuring original music by scott allen klopfenstein directed + choreographed by michael raine performed by the bats FEBRUARY 21 – APRIL 28 wednesdays @ 7PM, thursdays @ 9PM fridays and saturdays @ 11PM TICKETS S15 THE FLEA THEATER NIEGEL SMITH, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW, PRODUCING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF LOCKED UP BITCHES BOOK AND LYRICS BY CATYA MCMULLEN FEATURING ORIGINAL MUSIC BY SCOTT ALLEN KLOPFENSTEIN DIRECTED AND CHOREOGRAPHED BY MICHAEL RAINE FEATURING THE BATS LACY ALLEN, LEILA BEN-ABDALLAH, XANDRA CLARK, CHARLY DANNIS, JANUCHI URE EGBUHO, PHILIP FELDMAN, KATHERINE GEORGE, ARIELLE GONZALEZ, ALICE GORELICK, ALEX HAYNES, CRISTINA HENRIQUEZ, TIFFANY IRIS, ADAMA B. JACKSON, JENNY JARNAGIN, MARCUS JONES, BRE NORTHRUP, EMMA ORME, JUAN “SKITTLEZ” ORTIZ, JEN PARKHILL, ALEXANDRA SLATER, RYAN WESLEY STINNETT, TANYAMARIA, XAVIER VELASQUEZ, KEITH WEISS, TAMARA WILLIAMS SCOTT ALLEN KLOPFENSTEIN MUSIC DIRECTOR AND ARRANGER KERRY BLU CO-MUSIC DIRECTOR YU-HSUAN CHEN SCENIC AND PROPERTIES DESIGNER EVA JAUNZEMIS COSTUME DESIGNER JONATHAN COTTLE LIGHTING DESIGNER MEGAN DEETS CULLEY SOUND DESIGNER KIMILLE HOWARD AssISTANT DIRECTOR CODY HOM STAGE MANAGER CAST Pipsy ..................................................................................Emma Orme All-Licks ..........................................................................Charly Dannis Crazy Tongue ............................................................ Adama B. Jackson Bull ..................................................................... -

Allison Leyton Allison Leyton-Brown

Allison Leyton-Brown M.F.A., Tisch School of the Arts, NYU – Music Theatre Writing Program (Composition) B.F.A., Concordia University, Montréal – Interdisciplinary Fine Arts F I L M / T V S C O R E S . Episode score and songs for Peg + Cat for PBS. 2013 . Misc. music for 20/20, The Good Wife, Primetime, Good Morning America, ABC’s What Would You Do?, Nightline, Katie, The Nate Berkus Show, etc. Staff writer for 4 Elements Music. ’10 – present. The Bicycle (13 min.) Dramatic short. NY Film Festival, dir. Kari Riely. ’13. Rainy Season (25 min.) Documentary film. Screenings across the US and Europe, dir. Joan Widdenfield. ’11. Meet My Boyfriend (12 min.) Comedy short, dir. J. Ruocco, Manhattan Film Fest. ’11. Little Miss Perfect (series) for WE Network.’09 – ’10. The Cooking Loft (theme) for The Food Network. ’08. Custody (90 min.) Television film for Lifetime TV Network. Score selections. ’07. Millions: A Lottery Story (101 min) Documentary feature, dir. Paul LaBlanc, Palm Beach International Film Fest. Official Selection.’07. Head Case (85 min) Dark comedy feature, dir. M. Wakefield, Rio de Janeiro MIX Festival ’05 & New York City MIX Fest.’03. History of the Movies (1 min) dir. S. Donsky, Coca Cola Young Directors’ Competition National Finalist.’04. The Rest (10 min) dir. D. Franco, RIP Fest. NYC ’03. Dog’s Life (90 min) Dramatic feature, dir. J. Knapich, Telluride Film Festival, Brooklyn Underground Film Fest. ’02. T H E A T R E S C O R E S The Narrowing; recorded instrumental score for 2 pianos, cello & violin, produced by Archipelago Theatre, NC. -

Download Program

THE FLEA THEATER NIEGEL SMITH ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CAROL OSTROW PRODUCING DIRECTOR PRESENTS THE WORLD PREMIERE OF THE PLACE WE BUILT WRITTEN BY SARAH GANCHER DIRECTED BY DANYA TAYMOR FEATURING THE BATS BRITTANY K. ALLEN, LYDIAN BLOSSOM, TOM COSTELLO, BRENDAN DALTON, TAMARA DEL ROSSO, PHILIP FELDMAN, KRISTIN FRIEDLANDER, CLEO GRAY, RACHEL INGRAM, BEN LORENZ, ASH MCNAIR, SONIA MENA, ISABELLE PIERRE, XAVIER REMINICK, LETA RENÉE-ALAN, TESSA HOPE SLOVIS THE BENGSONS ARRANGEMENTS/MUSIC CONSULTANTS ARNULFO MALDONADO & FELI LAMEncA SCENIC DESIGN MASHA TSIMRING LIGHTING DESIGN CLAUDIA BROWN COSTUME DESIGN BEN TRUPPIN-BROWN SOUND DESIGN MARTE JOHAnnE EKHOUGEN PUPPET DESIGN ZACH SERAFIN PROPS MASTER ALEX J. GOULD FIGHT CHOREOGRAPHY JOCELYN CLARKE DRAMATURG CHARISE GREENE VOICE/DIALECT COACH BECKY HEISLER ASSOCIATE LIGHTING DESIGN IzzY FIELds COSTUME ASSISTANT JAKE BECKHARD ASSISTANT DIRECTOR TZIPORA REMAN STAGE MANAGER KAILA HILL ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER BRADLEY MEAD/WIIDE GRAPHIC DESIGNER RON LASKO/SPIN CYCLE PRESS REPRESENTATIVE CAST Aniko ..........................................................................Leta Renée-Alan Julia ......................................................................................Cleo Gray Kata ....................................................................... Kristin Friedlander Szuszanna ................................................................... Lydian Blossom Aisha ............................................................................ Isabelle Pierre Ilona .........................................................................Tamara -

Full Cast & Credits

DANSPACEPROJECT40 YOU MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. Help us celebrate 40 years of Danspace Project! Donate at danspaceproject.org/supportjoin ABOUT DANSPACE PROJECT Founded in 1974, Danspace Project presents new work in dance, supports a diverse range of choreographers in developing their work, encourages experimentation, and connects artists to audiences. Now in its fourth decade, Danspace Project has supported a vital community of contemporary dance artists in an environment unlike any other in the United States. Located in the historic St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, Danspace shares its facility with the Church, The Poetry Project, and New York Theatre Ballet. Danspace Project’s Commissioning Initiative has commissioned over 450 new works since its inception in 1994. Danspace Project’s Choreographic Center Without Walls (CW²) provides context for audiences and increased support for artists. Our presentation programs (including Platforms, Food for Thought, DraftWork), Commissioning Initiative, residencies, guest artist curators, and contextualizing activities and materials are core components of CW² offering a responsive framework for artists’ works. Since 2010, we have produced eight Platforms, published eight print catalogues and five e-books, launched the Conversations Without Walls discussion series, and explored models for public discourse and residencies. FOLLOW US! Facebook: Danspace Project Instagram: DanspaceProject Twitter: @DanspaceProject Tumblr:danspaceproject.tumblr.com www.danspaceproject.org BE FIRST. Join us in celebrating 40 -

Visibly Vibrant Visibly Noticed Vibrant Diverse Neighborhood

VISIBLY VIBRANT VISIBLY NOTICED VIBRANT DIVERSE NEIGHBORHOOD Hudson Square: One of Manhattan’s most historic yet up-and-coming neighborhoods Borders: TriBeCa, SoHo and Greenwich Village Rezoning Initiative: With the imminent rezoning of Hudson Square, the neighborhood is on the brink of a transformative moment, which will encourage its evolution into a 24/7 mixed use market. Once approved, the rezoning will allow for a burst of residential development, to include the following: • Potential for the addition of 3,500+ residential units over the next 10 years. • Residential occupancy will be boosted from 4% to 25%. • 429-foot tall residential tower, including a 420-seat school, at Canal Street and Sixth Avenue. • Site at 78-86 King Street slated for residential redevelopment is 40,000 sf with an additional 160,000 sf of air rights. KEY OFFICE TENANTS HUDSON SQUARE STATISTICS 335,000 SF 82,844 SF 2,363,853 SF Daytime Population 50,000 2012 Average Household Income $129,516 GLOBAL HEADQUARTERS 372,382 SF 237, 270 S F Number of Businesses 1,477 Number of Office Workers 26,098 Total Office Square Footage10.25 Million SF Annual Ridership A C Spring Street 3,589,809 Annual Ridership 1 Houston Street 4,225,089 271,940 SF 22,115 SF 316,594 SF 1,014 Hotel Rooms within 2 Blocks 721,171 SF 168,000 SF 225,474 SF PREMISES Ground Floor: North Retail 11,942 SF South Retail 3,357 SF Basement: Space A: 1,219 SF Space C: 1,019 SF Space D: 2,685 SF Space F: 424 SF CEILING HEIGHTS Ground Floor North Retail Ground: 16’ 3” – 18’ 3” South Retail Ground: 15’ Basement: 10’ 6” FRONTAGE North Retail: 64’ on Hudson St Outdoor Seating Basement 154’ on Charlton St Available South Retail: A 64’ on Hudson St 50’ on Vandam St POSSESSION C E B Immediate F North Retail LA Colombe TERM 11,942 SF Street Charlton StreetVandam Vandam Street Vandam Charlton Street Charlton Long-term D DIVISIONS Hudson Street Logical Divisions Considered ASKING RENT Office Building Lobby South Retail 3,357 SF Upon Request Hudson Street W 4TH ST BA RROW ST COMMERCE ST WA SHINGTON ST MORTON ST PL ’S BEDFORD ST ST.