A Project on Medieval Manuscripts: the Book of Kells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Making of the Book of Kells: Two Masters and Two Campaigns

The making of the Book of Kells: two Masters and two Campaigns Vol. I - Text and Illustrations Donncha MacGabhann PhD Thesis - 2015 Institute of English Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London 1 Declaration: I hereby declare that this thesis has not been submitted as an exercise for a degree at any other university, and that it is entirely my own work. _________________________________ Donncha MacGabhann 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the number of individuals involved in the making of the Book of Kells. It demonstrates that only two individuals, identified as the Scribe-Artist and the Master-Artist, were involved in its creation. It also demonstrates that the script is the work of a single individual - the Scribe-Artist. More specific questions are answered regarding the working relationships between the book’s creators and the sequence of production. This thesis also demonstrates that the manuscript was created over two separate campaigns of work. The comprehensive nature of this study focuses on all aspects of the manuscript including, script, initials, display-lettering, decoration and illumination. The first part of chapter one outlines the main questions addressed in this thesis. This is followed by a summary of the main conclusions and ends with a summary of the chapter- structure. The second part of chapter one presents a literature review and the final section outlines the methodologies used in the research. Chapter two is devoted to the script and illumination of the canon tables. The resolution of a number of problematic issues within this series of tables in Kells is essential to an understanding of the creation of the manuscript and the roles played by the individuals involved. -

The Texts of the Lindisfarne Gospels

chapter 10 The Texts of the Lindisfarne Gospels Richard Marsden Beneath its celebratory splendour, the Lindisfarne Gospels associating production of the gospel-book with the cult of is a text – or rather texts. What we encounter today, after St Cuthbert has no foundation in evidence, and the earli- the addition of an Old English translation above the Latin est reference to its origins, in the above-mentioned colo- text more than two centuries after the original copying, is phon, makes no reference to Cuthbert at all.2 The work is a bilingual gospel-book. As such, it is an unusually rich said there to have been dedicated simply to the ‘holy ones’ resource for historians of both text and language; but the (Old English halgum, saints or possibly the community processes of trying to assess the two texts and to under- itself) of Lindisfarne. Thus the year of St Cuthbert’s trans- stand the relationship between them are hampered by lation (698) and the launch of his cult are no longer neces- many anomalies and puzzles. Some of these derive from sary reference points in our conjectures about when the instabilities which are inherent in Bible texts (in Eadfrith copied out the gospels. Although some recent whatever language) in the medieval period, some are a estimates have stretched the likely period of copying consequence of the vagaries and accidents of manuscript towards the end of Eadfrith’s life, Gameson’s argument transmission, and some reflect the complex dynamics of that by 710 the bishop would have been too elderly to be the glossing process itself. -

Lost Incunable Editions: Closing in on an Estimate

chapter 3 Lost Incunable Editions: Closing in on an Estimate Jonathan Green and Frank McIntyre Imagine, if you will, that you are a lepidopterist stationed in the butterfly-rich environment of a tropical Malaysian island. You hope to determine the number of butterfly species that live on the island, and so you resolve to survey an acre- sized patch of it for a month and record the number of individuals of each spe- cies that you find. At the end of the month, you find that a few species of butterfly are represented by a large number of specimens, while many species are repre- sented by only one or a few specimens. These results lead you to suspect that there remain many species of butterfly on the island that your survey has missed, but how many? And how many more species can you expect to discover with additional months of observation? As your opportunity to spend additional months on a tropical island depends on your presenting a convincing argument to your funding agency, these questions are of some urgency for you. This is a brief statement of what is known as the unseen species problem, which has been an area of intense study both within and well outside of the field of ecology for several decades. The example above concerning Malaysian butterflies is drawn from a pathbreaking article published in 1943 by Ronald Fisher, one of the founders of modern biology and statistics, who proposed statistical methods for estimating the number of unseen butterfly species.1 Since then, the development and implementation of these methods has con- tinued, so that several current statistical software packages can provide both an estimate of the number of missing species and determine the confidence interval of that estimation, that is, the range within which one is reasonably certain the actual number lies.2 In an ideal situation, the number of observed butterfly species will rise with each additional month of observation, but the estimate of total species will change only modestly as the confidence interval 1 R.A. -

The Lindisfarne Gospels

University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Special Issue 03 | Winter 2014 http://www.forumjournal.org Title The Lindisfarne Gospels: A Living Manuscript Author Margaret Walker Publication FORUM: University of Edinburgh Postgraduate Journal of Culture and the Arts Issue Number Special Issue 03 Issue Date Winter 2014 Publication Date 20/01/2014 Editors Victoria Anker & Laura Chapot FORUM claims non-exclusive rights to reproduce this article electronically (in full or in part) and to publish this work in any such media current or later developed. The author retains all rights, including the right to be identified as the author wherever and whenever this article is published, and the right to use all or part of the article and abstracts, with or without revision or modification in compilations or other publications. Any latter publication shall recognise FORUM as the original publisher. FORUM | SPECIAL ISSUE 03 Walker 1 The Lindisfarne Gospels: A Living Manuscript Margaret Walker The University of Edinburgh This article questions how current and previous owners have marked the Lindisfarne Gospels, created 1,300 years ago. Their edits, which would be frowned upon today, are useful for historians to understand how the Gospels have been valued by previous owners and thus why they are so treasured today. The Lindisfarne Gospels are on display in the treasures gallery of the British Library. The eighth- century Insular manuscript is opened and accompanied by a short caption with information about the work. i It is presented as a 1,300-year-old masterpiece, which has survived to the present day against the odds of time. -

Johannes Gyllenmun – En Senmedeltida Ikonografisk Förvirring

Johannes Gyllenmun – en senmedeltida ikonografisk förvirring Eva Lindqvist Sandgren Title Saint John, the Golden-mouthed – a Late Mediaeval Iconographical Confusion Abstract The pictorial program in Thott 113, an illuminated French book of hours from c. 1400 in the Royal Library, Copenhagen, is fairly conventional. But instead of the usual evangelist portrait at the beginning of the gospel, St. John is placed on the island of Patmos, where his writing is inter- rupted by a devil who steals his ink. This motif became popular around the middle of the 15th cen- tury in northern France and Flanders, a fact previously noticed by scholars. In this article, however, the motif is connected to Parisian book illumination from a slightly earlier period, i.e. the late 14th or early 15th century, and to some of the illuminators working for Duke Jean de Berry (d. 1416). The motif originated through a confusion of John the evangelist with John Chrysostom. It can be con- nected to a Miracle play, performed annually by the goldsmiths’ guild in Paris during the 14th cen- tury. The book illuminators who used the scene included, for example, the Vergil Master, although the painter of the Thott hours in Copenhagen, the Ravenelle Master, seems to have used it even more frequently. Keywords Miniatures, late medieval book illumination, John the evangelist, John of Patmos, John Chrysostom, Jean bouche d’or, devil, ink horn, Miracle play, Parisian book illumination, Bible his- toriale, book of hours, gold smiths’ guild Author Associate prof./senior lecturer, Dept. of Art History, Uppsala University Email [email protected] Iconographisk Post Nordisk tidskrift för bildtolkning • Nordic Review of Iconography Nr 1, 2015, pp. -

An Introduction to William Shakespeare's First Folio

An Introduction to William Shakespeare’s First Folio By Ruth Hazel Cover illustration courtesy of Stephen Collins This eBook was produced by OpenLearn - The home of free learning from The Open University. It is made available to you under a Creative Commons (BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. 2 Brush up your Shakespeare The comic gangsters in Kiss Me Kate, Cole Porter’s 1948 musical based on Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, offer Shakespeare’s poetry – by which they actually mean his plays – as a guaranteed way to a woman’s heart: quoting Shakespeare will impress her and be a sure-fire aphrodisiac. Today, Shakespeare has become a supreme icon of Western European high culture, which is ironic since in his own day Shakespeare’s craft – jobbing playwright – was not a well-regarded one. Indeed, those who wrote plays to entertain the ‘groundlings’ (as the people who paid just one penny to stand in the open yard round the stage in public playhouses were called) were often considered little better than the actors themselves – who, in their turn, were only one level up, in the minds of Puritan moralists, from whores. Shakespeare himself did not seem eager to advertise authorship of his plays by seeing them into print, and when some of his plays were printed, in the handy quarto-sized editions for individual consumption, his name was not always on the title page. (The terms ‘folio’ and ‘quarto’ refer to the size of the pages in a book: in a Folio, each sheet of paper was folded just once, with a page height of approx. -

The Octavo Package Stefan A

TUGboat, Volume 23 (2002), No. 3/4 269 The Octavo Package Stefan A. Revets Abstract The Octavo package is a modification of the standard LATEX book class, written to help produce books of clas- sical design, format and layout. The page sizes made available are the classical octavo sizes and the margins are calculated according to late Gothic precepts. An at- tempt is made to maintain the uniformity of the printing grid, and display is kept unobtrusive. − − ∗ − − 1 Introduction Donald Knuth developed TEX because of his grow- ing dissatisfaction with the commercial typesetting of his books `The Art of Computer Programming' [4]. The program grew into a typesetting system, with a great deal of attention and ingenuity devoted to the calculations of the placement of letters, words and paragraphs on the page. The preface of the TEXbook begins with the words `This is a handbook about TEX, a new typesetting system intended for the creation of beautiful books . ' [3]. More people began to use TEX, and, with the advent of LATEX, ready-made class files became part of the system. The standard style and class files tended to show off the capabilities of the system, rather than con- form to good design. Philip Taylor put it with some humour and considerable precision: `Knuth, in his closing exhortation, wrote: \Go forth now and create masterpieces of the publishing art." Nowhere, so far as I can trace, did he write: \and let every one of them shriek `TEX' from every page". ' [9]. Class files have been proposed and are available from CTAN which give the more fastidious user the means with which to moderate at least some of the excesses of these standard LATEX styles. -

Book Burning and Censorship

THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS 0. THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS - Story Preface 1. WHY FREE EXPRESSION? 2. FREE EXPRESSION IN BOOKS 3. THE DIAMOND SUTRA 4. THE LINDISFARNE GOSPELS 5. THE PRECIOUS MANUSCRIPTS 6. JOHN WYCLIFFE'S BOOKS 7. JOHN HUS BURNS 8. TYNDALE WRITES, THEN BURNS 9. LUTHER'S TRANSLATIONS ARE BURNED 10. THE PRINTING PRESS 11. BOOKS BURN IN THE NEW WORLD 12. CENSORSHIP CONTINUES 13. BURNING CONTINUES 14. CHERISHED RIGHTS 15. MORE COOL LINKS Folio 27r of the Lindisfarne Gospels. Depicted here is the beginning of the Gospel of Matthew. Image online via Wikimedia Commons. Today we can examine the work of one monk, Eadrith (later the Bishop of Lindisfarne), who produced a stunning example of book painting that is even older than the Diamond Sutra. Although the manuscript is undated, The Lindisfarne Gospels were likely copied and illustrated by Eadrith while he was still a monk at Lindisfarne Priory, on Holy Island (off the English Northumberland coast). Nothing remains of the original monastery. Since Eadrith became Bishop in 698 AD—the date scholars typically use forthe manuscript—St. Bilfrid bound the manuscript and added precious gems and metalwork to its binding. Currently owned by the British Library, the Lindisfarne Gospels contain notes from a priest, Aldred, who also inserted a word-for-word Anglo-Saxon translation in the spaces between the lines of Latin text. Those insertions were probably made between 950 and 970 AD. In the meantime, the monks had fled looting Vikings who, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, invaded the area (be sure to activate "fly" to "view" this virtual-tour animation) duringJanuary of 793. -

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (C

St Cuthbert Part 1 Saint Cuthbert (634-687) Generally Cuthbert (c. 634 – 20 March 687) is a saint of the early Northumbrian church in the Celtic tradition. He was a monk, bishop and hermit, associated with the monasteries of Melrose and Lindisfarne in what might loosely be termed the Kingdom of Northumbria. After his death he became one of the most important medieval saints of Northern England, with a cult centred on his tomb at Durham Cathedral. Cuthbert is regarded as the patron saint of Northern England. His feast day is 20 March (Catholic Church and Church of England), Stained glass depicting St Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, from Gloucester Cathedral History of the St Cuthbert era Lots of small areas ruled by Kings. See map above. The population had just become Christian after a visit from Roman priests. Christian/ pagan fluctuation. There was also a conflict between the Irish way of worshiping and the Roman way. The Irish priests came from Iona on the other side of Scotland, the /west coast. New monasteries were founded, Lindisfarne, Melrose and Ripon. Vikings invade and destroy Lindisfarne in 793 and Iona (st Columbia’s stronghold) 2 years later. 1. King Edwin: Converted to Christianity in 627, which was slowly followed by the rest of his People. The politics of the kingdom were violent, and there were later episodes of pagan rule, spreading understanding of Christianity through the kingdom was a task that lasted throughout Cuthbert's lifetime. Edwin had been baptised by Paulinus of York, an Italian who had come with the Gregorian mission from Rome. -

INCUNABULA of the CLEVELAND MEDICAL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION* Montagnan a , Bartholomaeus

INCUNABULA OF THE CLEVELAND MEDICAL LIBRARY ASSOCIATION* Montagnan a , Bartholomaeus. Consilia [Translated by Paravicius.]—A verroes. CoIIi- medica; tractatus de balneis et de fabribus get. Editio Princeps. Venice, Joannes and cum aliis quibusdam. Editio Princeps. Padua, Gregorius de Gregoriis, de Forlivio, 1490. Laurentius Canozius? 1477? Folio. Folio. Rhaze s . Liber nonus ad Almansorem cum Ser apio n , Joannes. Liber aggregatus in expositione Sillani de Nigris.—Receptae Petri medicinis simplicibus. [Translated into Latin de Tussignano supra nonum ad Almansorem. by Simon Januensis.] Venice, Reynaldus de Venice, [Bonetus Locatellus] for Octavianus Novimagio, 1479. Scotus, 1490. Folio. Folio. Serap ion , Joannes. Brevarium medicinae. Avice nna . Canon de medicina. [Translated Editio Princeps. Venice, Reynaldus de Novi- into Latin by Gerardus Cremonensis and with magio, 1479. Commentary by Gentilis de Fulgineo.] Venice, Folio. Baptista de Tortis. 1490-1495. Hugo Sene ns is (Ugo Benzo ). Super Large folio. quarta fen primi Canonis Avicennae. [Com- Gul iel mus de Sal ice to . Summa con- pleted by Marsilius de Sancta Sophia.] servationis et curationis. Chirugia. Venice, Editio Princeps. Venice, Andreas Calabrensis [Marinus Saracenus] 1490. (Papiensis), 1485. Folio. Folio. Jacobu s Foroli viens is [Giacomo Della Savona rola , Joannes Michael. Practica Torre] Expositio in aphorismos Hippocratis. de egritudinibus a capite usque ad pedes. Venice, Philippus Pincius, 1490. Venice, Andreas de Bonetis de Papia, i486. Folio. Folio. Picus Moran dulan us , Joannes. Heptaplus Rhaze s , or Abu Bakr , Muhammed. EI- de septiformi sex dierum geneseos enerratione. havi: Hoc est liber continens artem medicinae. Editio Princeps. [Florence, Bartolommeo di [Translated from Arabic into Latin by Libri, c. 1490.] Feragius, a doctor of Salerno.] Editio Prin- Folio. -

The Illustrated Book Cover Illustrations

THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: A collection of 18 pronouncements by Buddhist sages accompanied by their pictures. n.p., n.d. Manuscript scroll folded into 42 pages, written on leaves of the bodhi tree. Chinese text, beginning with the date wu-shu of Tao kuang [·i.e. 1838 ] Wooden covers. Picture of Buddhist sage Hsu tung on front cover, accompanied by text of his pronouncement on separate leaf on back cover: "A Buddhist priest asked Buddha, 'How did the Buddha attain the most superior way?' Buddha replied, 'Protect the heart from sins; as one shines a mirror by keeping off dust, one can attain enlightenment.'" --i~ ti_ Hsu tung THE ILLUSTRATED BOOK • An Exhibit: March-May 1991 • Compiled by Alice N. Loranth Cleveland Public Library Fine Arts and Special Collections Department PREFACE The Illustrated Book exhibit was assembled to present an overview of the history of book illustration for a general audience. The plan and scope of the exhibit were developed within the confines of available exhibit space on the third floor of Main Library. Materials were selected from the holdings of Special Collections, supplemented by a few titles chosen from the collections of Fine Arts. Selection of materials was further restrained by concern for the physical well-being of very brittle or valuable items. Many rare items were omitted from the exhibit in order to safeguard them from the detrimental effects of an extended exhibit period. Book illustration is a cooperation of word and picture. At the beginning, writing itself was pictorial, as words were expressed through pictorial representation. -

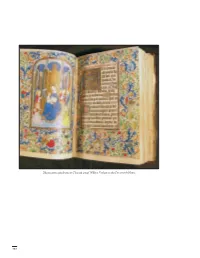

Illumination Attributed to Flemish Artist Willem Vrelant in the Farnsworth Hours

Illumination attributed to Flemish artist Willem Vrelant in the Farnsworth Hours. 132 Book Arts a Medieval Manuscripts Georgetown’s largest collection of late medieval and early renaissance documents, the Scheuch Collection, is described in the European History chapter. In addition to that collection, the library possesses nearly a score of early liturgical and theological manuscripts, including some with interesting and sometimes significant miniatures and illumina tion. Those held prior to 1970 are for the most part listed in Seymour de Ricci’s Census or its supplement, but special note should be made of the volume of spiritual opuscules in Old French (gift of John Gooch) and the altus part of the second set of the musical anthology known as the “Scots Psalter” (1586) by Thomas Wode (or Wood) of St. Andrews, possibly from the library of John Gilmary Shea. Also of note are two quite remarkable fifteenth-century manuscripts: one with texts of Bede, Hugh of St. Victor, and others (gift of Ralph A. Hamilton); the other containing works by Henry of Hesse, St. John Chrysostom, and others (gift of John H. Drury). In recent years the collection has Euclid, Elementa geometriae (1482). grown with two important additions: a truly first-rate manuscript, the Farnsworth Hours, probably illuminated in Bruges about 1465 by Willem Vrelant (gift of Mrs. Thomas M. Evans), and a previously unrecorded fifteenth-century Flemish manuscript of the Imitatio Christi in a very nearly contemporary binding (gift of the estate of Louise A. Emling). The relatively small number of complete manuscripts is supplemented, especially for teaching purposes, by a variety of leaves from individual manuscripts dating from the twelfth to the sixteenth century (in part the gifts of Bishop Michael Portier, Frederick Schneider, Mrs.