Northumbria Research Link

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lillo&Greg Arteteca Ruffini De Santis Guarneri

LUIGI E AURELIO DE LAURENTIIS PRESENTANO PAOLO LILLO&GREG NINO RUFFINI ELEONORA FRASSICA GIOVANARDI UCCIO ENRICO DE SANTIS ARTETECA GUARNERI STUDIO STUDIO PHOTO: ANTONELLO&MONTESI PHOTO: ANTONELLO&MONTESI UN FILM FILMAURO PRESSBOOK PRODUTTORE ESECUTIVO MAURIZIO AMATI PRODOTTO DA REGIA DI AURELIO&LUIGI VOLFANGO DE BIASI DE LAURENTIIS PRESSBOOK UFFICIO STAMPA FILM UFFICIO STAMPA FILMAURO Valentina Guidi e Mario Locurcio Martina Riva e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Cell. Valentina: 335 6887778 - Mario: 335 8383364 Tel. 06.6995845 7 - Cell. 347 4828978 SEGUICI SU CREDITI NON CONTRATTUALI www.filmauro.it 2 PERSONAGGI ED INTERPRETI PERSONAGGI ED INTERPRETI Erminio Lillo (Pasquale Petrolo) Prisco Greg (Claudio Gregori) Vanni Paolo Ruffini ‘U Barone Nino Frassica Anita Eleonora Giovanardi Monica Monica Lima (Arteteca) Enzo Enzo Iuppariello (Arteteca) Mike The Hammer Vincent Riotta Er Duca Ninetto Davoli Barese Uccio De Santis ‘U Mago Enrico Guarneri Sua Maestà La Regina Patricia Ford CAST TECNICO Regia Volfango De Biasi Soggetto Volfango De Biasi, Alessandro Bencivenni, Tiziana Martini, Felice Di Basilio, Andrea Careri. Sceneggiatura Volfango De Biasi, Alessandro Bencivenni, Tiziana Martini, Gianluca Ansanelli, Marco Bonini, Paola T. Cruciani Fotografia Tani Canevari Scenografia Giuliano Pannuti Costumi Tatiana Romanoff Montaggio Stefano Chierchiè Organizzatore generale Edmondo Amati Produttore esecutivo Maurizio Amati Prodotto da Aurelio De Laurentiis & Luigi De Laurentiis Distribuzione FILMAURO Uscita 15 dicembre 2016 DIO SALVI LA REGINA 3 SINOSSI Londra. Due fratelli pasticcioni alle prese con una bella chef stellata ed il suo toscanissimo sous chef… Un piatto sopraffino, un mare di risate e nientedimeno che… la Regina d’Inghilterra!! Gli ingredienti ci sono tutti per mettere a segno un colpo sensazionale: rapire i preziosissimi cani di Sua Maestà e travolgere Buckingham Palace. -

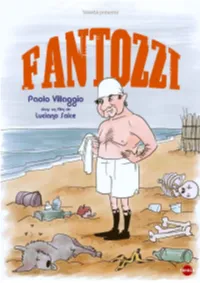

Ce N'est Pas À Moi De Dire Que Fantozzi Est L'une Des Figures Les Plus

TAMASA présente FANTOZZI un film de Luciano Salce en salles le 21 juillet 2021 version restaurée u Distribution TAMASA 5 rue de Charonne - 75011 Paris [email protected] - T. 01 43 59 01 01 www.tamasa-cinema.com u Relations Presse Frédérique Giezendanner [email protected] - 06 10 37 16 00 Fantozzi est un employé de bureau basique et stoïque. Il est en proie à un monde de difficultés qu’il ne surmonte jamais malgré tous ses efforts. " Paolo Villaggio a été le plus grand clown de sa génération. Un clown immense. Et les clowns sont comme les grands poètes : ils sont rarissimes. […] N’oublions pas qu’avant lui, nous avions des masques régionaux comme Pulcinella ou Pantalone. Avec Fantozzi, il a véritablement inventé le premier grand masque national. Quelque chose d’éternel. Il nous a humiliés à travers Ugo Fantozzi, et corrigés. Corrigés et humiliés, il y a là quelque chose de vraiment noble, n’est-ce pas ? Quelque chose qui rend noble. Quand les gens ne sont plus capables de se rendre compte de leur nullité, de leur misère ou de leurs folies, c’est alors que les grands clowns apparaissent ou les grands comiques, comme Paolo Villaggio. " Roberto Benigni " Ce n’est pas à moi de dire que Fantozzi est l’une des figures les plus importantes de l’histoire culturelle italienne mais il convient de souligner comment il dénonce avec humour, sans tomber dans la farce, la situation de l’employé italien moyen, avec des inquiétudes et des aspirations relatives, dans une société dépourvue de solidarité, de communication et de compassion. -

RAPPORTO Il Mercato E L’Industria Del Cinema in Italia 2008

RAPPORTO Il Mercato e l’Industria del Cinema in Italia 2008 fondazione ente dello spettacolo RAPPORTO Il Mercato e l’Industria del Cinema in Italia 2008 In collaborazione con CINECITTA’ LUCE S.p.A. Con il sostegno di Editing e grafica: PRC srl - Roma fondazione ente Realizzazione a cura di: Area Studi Ente dello Spettacolo Consulenza: Redento Mori dello spettacolo Presentazione el panorama della pubblicistica italiana sul cinema, è mancata fino ad oggi una sintesi che consentisse una visione organica del settore e tale da misurare il peso di una realtà produttiva che per qualità e quantità rappresenta una delle voci più significative Ndell’intera economia. Il Rapporto 2008 su “Il Mercato e l’Industria del Cinema in Italia” ha lo scopo primario di colmare questa lacuna e di offrire agli operatori e agli analisti un quadro più ampio possibile di un universo che attraversa la cultura e la società del nostro Paese. Il Rapporto è stato realizzato con questo spirito dalla Fondazione Ente dello Spettacolo in collaborazione con Cinecittà Luce S.p.A., ed è il frutto della ricerca condotta da un’équipe di studiosi sulla base di una pluralità di fonti e di dati statistici rigorosi. Questo rigore si è misurato in alcuni casi con la relativa indeterminatezza di informazioni provocata dall’assenza di dati attualizzati (ad esempio, per i bilanci societari) e dalla fluidità di notizie in merito a soggetti che operano nel settore secondo una logica a volte occasionale e temporanea. La Fondazione Ente dello Spettacolo opera dal 1946. Finora si è conosciuto molto del cinema italiano soprattutto in termini di È una realtà articolata e multimediale, impegnata nella diffusione, promozione consumo. -

La Transgression Dans L'œuvre De David Cronenberg

Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Ecole doctorale Arts plastiques, esthétique et sciences de l'art Thèse pour l'obtention du grade de docteur de l'Université Paris 1 Présentée et soutenue publiquement par : Fabien Demangeot La transgression dans l'œuvre de David Cronenberg Directeur de thèse : M. Vincent Amiel, Paris 1 Jury : M. Vincent Amiel, professeur des Universités, Paris 1 Mme Raphaëlle Moine, professeure des Universités, Paris 3 M. Anthony Fiant, professeur des Universités, Rennes 2 M. David Roche , professeur des Universités, Toulouse Jean Jaurès M. David Vasse, Maître de conférence, Université de Caen-Normandie 1 2 Remerciements Je tiens, tout d'abord, à remercier Vincent Amiel pour sa disponibilité et ses précieux conseils qui m'ont permis de mener à bien ce travail de recherches. Je remercie également mes parents et ma grand-mère pour leur soutien et leur aide durant ces trois années. 3 Table des matières Remerciements........................................................p. 3. Table des matières simplifiée...................................p. 4. Résumé/Abstract.......................................................p. 5-6. Introduction................................................................p. 7-34. Partie 1 : Transgresser la morale.................................p. 35-193. Partie 2 : Transgresser le corps....................................p. 194-322. Partie 3 : Transgresser le réel.......................................p. 323-438. Partie 4 : Transgresser le cinéma..................................p. 439-551. Conclusion.....................................................................p. -

Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 1 Journeys into Perversion: Vision, Desire and Economies of Transgression in the Films of Jess Franco Glenn Ward Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex May 2011 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been, and will not be, submitted whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature:……………………………………… 3 Summary Due to their characteristic themes (such as „perverse‟ desire and monstrosity) and form (incoherence and excess), exploitation films are often celebrated as inherently subversive or transgressive. I critically assess such claims through a close reading of the films of the Spanish „sex and horror‟ specialist Jess Franco. My textual and contextual analysis shows that Franco‟s films are shaped by inter-relationships between authorship, international genre codes and the economic and ideological conditions of exploitation cinema. Within these conditions, Franco‟s treatment of „aberrant‟ and gothic desiring subjectivities appears contradictory. Contestation and critique can, for example, be found in Franco‟s portrayal of emasculated male characters, and his female vampires may offer opportunities for resistant appropriation. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR in FILM

ABSTRACT Title of Document: COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Master of Arts, 2014 Directed By: Dr. Patrick Warfield, Musicology The horror film soundtrack is a complex web of narratological, ethnographic, and semiological factors all related to the social tensions intimated by a film. This study examines four major periods in the zombie’s film career—the Voodoo zombie of the 1930s and 1940s, the invasion narratives of the late 1960s, the post-apocalyptic survivalist fantasies of the 1970s and 1980s, and the modern post-9/11 zombie—to track how certain musical sounds and styles are indexed with the content of zombie films. Two main musical threads link the individual films’ characterization of the zombie and the setting: Othering via different types of musical exoticism, and the use of sonic excess to pronounce sociophobic themes. COMMUNICATING FEAR IN FILM MUSIC: A SOCIOPHOBIC ANALYSIS OF ZOMBIE FILM SOUNDTRACKS by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2014 Advisory Committee: Professor Patrick Warfield, Chair Professor Richard King Professor John Lawrence Witzleben ©Copyright by Pedro Gonzalez-Fernandez 2014 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS II INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 1 Introduction 1 Why Zombies? 2 Zombie Taxonomy 6 Literature Review 8 Film Music Scholarship 8 Horror Film Music Scholarship -

Mettono E Garantiscono Appuntamenti Alla Rai, Si

PUPI AVATI PRIME E ULTIME FOLLIE DI P.A. LA MAZURKA DEL BARONE, DELLA SANTA si cercano contatti, si trovano intermediari che in cambio di soldi pro- E DEL FICO FIORONE mettono e garantiscono appuntamenti alla Rai, si incontrano contesse 1974 decadute, amanti di politici, portaborse di politici, assistenti di assistenti di assistenti alla produzione, si frequentano case, si incontra gente: una È uno dei momenti più cupi nel cammino di Pupi Avati. Ha fatto fauna di mostri terribili che navigano sotto il pelo dell’acqua della capi- due film che sono stati commercialmente due flop, vive un momento tale pronti ad azzannare le prede che arrivano dalla provincia. personale difficile, è naufragato il sogno della Hollywood sul Reno, ha “Quattro anni di marciapiedi romani, confuso in una massa di indi- una famiglia da mantenere che non riesce a mantenere (già due figli, vidui muniti a loro volta del loro copione e della loro legittima attesa. Mariantonia nata nel ’66 e Tommaso nel ’69 mentre il terzo, Alvise, ar- Tutti a condividere l’opportunità che conducesse direttamente alla glo- riverà nel ’71), il lavoro alla Findus è stato abbandonato perché quando ria. Marciavo con loro, suonavo gli stessi campanelli, salivo le stesse scale, il cinema entra così in profondità nel sangue è praticamente impossibile mi presentavo alle stesse scortesissime segretarie, imploravo i medesimi tornare alla vita borghese: bisogna continuare a navigare in mari burra- appuntamenti. Ma io di occasioni ne avevo già avute due e le avevo scosi e sconosciuti, bisogna confidare in maniera irrazionale sulla propria sprecate. A Roma si sapeva. -

Diapositive 5 Casiraghi N

DIAPOSITIVE 5 CASIRAGHI N. INVENTARIO 198404 : ITALIA ’40-’50 [1.] diapositive n. 40 Don Pasquale / Camillo Mastrocinque,Armando Falconi. 1940 diapositive n.1 Tosca / Carl Koch, 1941, con Imperio Argentina, Michel Simon 2 A che servono questi quattrini / Esodo Pratelli, 1942, con E. e P. De Filippo 8 Maria Malibran / Guido Frignone, 1943 1 La vita ricomincia / Mario Mattoli, 1945 , con Alida Valli 2 L’Elisir d’amore / Mario Costa, 1946, con Silvana Mangano 2 Avanti a lui tremava tutta Roma / Carmine Gallone, 1946 1 Che tempi! / Giorgio Bianchi, 1947, con Walter Chiari, Lea Padovani 4 Natale al campo 119 / Pietro Francisci, 1947, (il manifesto) A. Fabrizi, V. De Sica 4 Follie per l’Opera / Mario Costa, 1947 (manifesto) 2 Rigoletto / Carmine Gallone, 1947 1 Assunta Spina / Mario Mattoli, 1947, con Anna Magnani, Eduardo De Filippo 5 Anni difficili / Luigi Zampa, 1948 2 Cesare Zavattini 1 Marcello Mastroianni primi anni cinquanta 1 Olivetti, Ferrara, Silone 1 Di Vittorio, A.C.Jemolo 1 Brancati, Comencini, Moravia 1 N. INVENTARIO 198405 : [ITALIA] ANNI ’40-’50 [2.] diapositive n. 35 Catene / Raffaello Matarazzo, 1950 diapositive n. 3 Napoleone / Carlo Borghesio ; 1951, con Renato Rascel 4 I figli di nessuno / Raffaello Matarazzo, 1951 2 Totò a colori / Steno, (il manifesto) , 1952 4 Passaporto per l’Oriente / Alessandrini Goffredo, 1952, con Gina Lollobrigida 2 Aida / Clemente Fracassi, 1953 , con Sophia Loren… 10 Caso Renzi – Aristarco, 1953 copertina Cinema Muto 1 Rigoletto e la sua tragedia / Flavia Calzavara, 1954 4 Italia K2 / Marcello Baldi, 1954 1 Totò all’inferno / Mastrocinque, 1955 2 La banda degli onesti / Camillo Mastrocinque, 1956, Totò Peppino De Filippo 1 Totò truffa’62 / Camillo Mastrocinque, 1961 1 N. -

Narcocorridos As a Symptomatic Lens for Modern Mexico

UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Vol. 1, No. 2 “Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro “The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic Fetishism and Fan Engagement with and Anthropological Lens to the War Horror Scores” on Drugs in Mexico” Spencer Slayton Samantha Cabral “Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s “This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Extremity in Thomas Adès’s The Acceptance in Shrek the Musical” Exterminating Angel” Clarina Dimayuga Lori McMahan “Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema” Liv Slaby Spring 2020 Editor-in-Chief J.W. Clark Managing Editor Liv Slaby Review Editor Gabriel Deibel Technical Editors Torrey Bubien Alana Chester Matthew Gilbert Karen Thantrakul Graphic Designer Alexa Baruch Faculty Advisor Dr. Elisabeth Le Guin 1 UCLA Department of Musicology presents MUSE An Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 1, Number 2 Spring 2020 Contents Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement 2 with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton Callowness of Youth: Finding Film’s Extremity in Thomas Adès’s 10 The Exterminating Angel Lori McMahan The Narcocorrido as an Ethnographic and Anthropological Lens to 18 the War on Drugs in Mexico Samantha Cabral This Is Our Story: The Fight for Queer Acceptance in Shrek the 28 Musical Clarina Dimayuga Cats: Culturally Significant Cinema 38 Liv Slaby Contributors 50 Closing notes 51 2 Grave-Digging Crate Diggers: Retro Fetishism and Fan Engagement with Horror Scores Spencer Slayton he horror genre is in the midst of a renaissance. The slasher craze of the late 70s and early 80s, revitalized in the mid-90s, is once again a popular genre for Treinterpretation by today’s filmmakers and film composers. -

Quentin Tarantino Retro

ISSUE 59 AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER FEBRUARY 1– APRIL 18, 2013 ISSUE 60 Reel Estate: The American Home on Film Loretta Young Centennial Environmental Film Festival in the Nation's Capital New African Films Festival Korean Film Festival DC Mr. & Mrs. Hitchcock Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Howard Hawks, Part 1 QUENTIN TARANTINO RETRO The Roots of Django AFI.com/Silver Contents Howard Hawks, Part 1 Howard Hawks, Part 1 ..............................2 February 1—April 18 Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances ...5 Howard Hawks was one of Hollywood’s most consistently entertaining directors, and one of Quentin Tarantino Retro .............................6 the most versatile, directing exemplary comedies, melodramas, war pictures, gangster films, The Roots of Django ...................................7 films noir, Westerns, sci-fi thrillers and musicals, with several being landmark films in their genre. Reel Estate: The American Home on Film .....8 Korean Film Festival DC ............................9 Hawks never won an Oscar—in fact, he was nominated only once, as Best Director for 1941’s SERGEANT YORK (both he and Orson Welles lost to John Ford that year)—but his Mr. and Mrs. Hitchcock ..........................10 critical stature grew over the 1960s and '70s, even as his career was winding down, and in 1975 the Academy awarded him an honorary Oscar, declaring Hawks “a giant of the Environmental Film Festival ....................11 American cinema whose pictures, taken as a whole, represent one of the most consistent, Loretta Young Centennial .......................12 vivid and varied bodies of work in world cinema.” Howard Hawks, Part 2 continues in April. Special Engagements ....................13, 14 Courtesy of Everett Collection Calendar ...............................................15 “I consider Howard Hawks to be the greatest American director. -

Dalle 9 Alle 13) +39 331 433 49 57 +39 333 255 17 58

Lim Antiqua s.a.s - Studio bibliografico Via delle Ville I, 1008 I-55100 LUCCA Telefono e Fax +39 0583 34 2218 (dalle 9 alle 13) +39 331 433 49 57 +39 333 255 17 58 web: www.limantiqua.it email: [email protected] P. IVA 01286300460 Dati per bonifico: C/C postale n. 11367554 IBAN: IT 67 Q 07601 13700 000011367554 BIC: BPPIITRRXXX Orario di apertura Lunedì – Venerdì ore 9.00/14.00 Gli ordini possono essere effettuati per telefono, email o via fax. Il pagamento può avvenire tramite contrassegno, bollettino postale, bonifico sul conto postale o PayPal. Le spese di spedizione sono a carico del destinatario. I prezzi indicati sono comprensivi di IVA. Gli ordini saranno ritenuti validi e quindi evasi anche in caso di disponibilità parziale dei pezzi richiesti. ATTRICI E ATTORI DEL CINEMA ITALIANO p. 4 TELEVISIONE E MUSICA LEGGERA p. 74 ATTRICI E ATTORI DEL CINEMA ITALIANO 1. Paola Bàrbara (Roma 1912 - Anguillara Sabazia 1989) Firma autografa su fotografia d’autore(23x16,2 cm) dello studio fotografico Montabone di Firenze, datata 1938, raffigurante l’attrice italiana, talvolta accreditata con lo pseudonimo “Pauline Baards”. Segni di pennarello sul retro della foto, peraltro ottimo esemplare. € 120 !4 2. Nino Besozzi (Milano 1901 - ivi 1971) Firma autografa e dedica manoscritta su fotografia d’autore (cm 22,5x16,8) dello studio fotografico Ermini di Milano, datata 1955., raffigurante il ritratto dell’attore cinematografico e teatrale milanese.€ 80 3. Nino Besozzi (Milano 1901 - ivi 1971) Firma autografa e dedica manoscritta su fotografia (cm 14,5x10,5) dello studio fotografico Ermini di Milano, datata 1960, raffigurante l’attore cinematografico e teatrale milanese. -

ENNIO FLAIANO Il Notiziario Del Sistema Bibliotecario Urbano Di Brescia Aprile 2010

Numero 9 ExLibris ENNIO FLAIANO Il Notiziario del Sistema Bibliotecario Urbano di Brescia aprile 2010 ENNIO FLAIANO (1910-2010) nel centenario della nascita Pagina 2 Ennio Flaiano (1910-2010), nel centenario della nascita - Rassegna audio-video-bibliografica - A cura di: Stefano Grigolato Maddalena Piotti Luigi Radassao Brescia, aprile 2010 Il Notiziario del Sistema Bibliotecario Urbano di Brescia Pagina 3 Ennio Flaiano nasce a Pescara il 5 marzo 1910. Tra i colti nel fondo Flaiano presso la Biblioteca Cantonale di vari spostamenti che caratterizzeranno la sua infanzia Lugano. Dopo essere stato colpito nel 1971 da un pri- (Camerino, Senigallia, Fermo, Chieti) una tappa verrà mo infarto, Flaiano inizia a rimettere ordine tra le sue fatta anche a Brescia, dove trascorrerà l’anno scolasti- carte: il suo intento è quello di pubblicare una raccolta co 1921/22. A Brescia tornerà nel 1939, in occasione di organica di tutti quegli appunti sparsi che rappresenta- una mostra sulla Pittura del Rinascimento. Nell’articolo no la sua instancabile vena creativa. Muore a Roma il dedica un ampio spazio ad una positiva descrizione 20 novembre 1972, colpito da un secondo infarto che della cittàe dei suoi abitanti: “ Lo svolgersi dei suoi porti- gli sarà fatale, lasciando moltissimo materiale inedito ci accoglienti, lo sfociare delle sue vie in piazze riparate che verrà pubblicato dopo la sua morte. Di lui disse e chiuse come saloni da ballo, il rispetto di un modulo Enrico Vaime: “ L'uomo più intelligente che abbia mai latino degli edifizi basterebbero forse a convincere…. incontrato. Il più spiritoso. Reagiva alla cupezza del suo del carattere unico… di questa città.