Judicial System of Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

We Honour the Pouring Tradition…

Beer iis to Bellgiium as wiine iis to France and whiisky iis to Scotlland. Bellgiians can choose from over 800 diifferent brews from around 100 breweriies. These breweriies are known for theiir perfect ballance of hiigh qualliity, advanced bllendiing methods and state of the art technollogy. The resullts are here for you to enjoy. We honour the pouring tradition… I The Purification, your bartender will always use a clean glass, which is rinsed and then chilled with cold water, allowing the glass to reach the same temperature as the beer. II The Sacrifice, ensuring every drop of beer is fresh, your bartender allows the first foams from the tap to wash away. III The Liquid Alchemy Begins, the chalice is held at 45 degree angle allowing the perfect amount of foam to start forming the head of the beer. IV The Head, the glass is straightened and the head forms creating the vital protection for the beer ensuring maximum freshness and flavour. V The Removal, your bartender then closes the tap in one swift motion and moves the glass away to prevent drips entering the beer that have had contact with the air, these drops have oxidized and are not worthy of your beer. VI The Beheading, while the head is still forming, your bartender cuts it gently with a knife to eliminate the larger bubbles, bursting easily they accelerate the dissipation of the head. VII The Cleansing, your bartender rinses the bottom and sides of your glass, this keeps the outside of the chalice clean and comfortable to hold. -

Sectorverdeling Planning En Kwaliteit Ouderenzorg Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen

Sectorverdeling planning en kwaliteit ouderenzorg provincie Oost-Vlaanderen Karolien Rottiers: arrondissementen Dendermonde - Eeklo Toon Haezaert: arrondissement Gent Karen Jutten: arrondissementen Sint-Niklaas - Aalst - Oudenaarde Gemeente Arrondissement Sectorverantwoordelijke Aalst Aalst Karen Jutten Aalter Gent Toon Haezaert Assenede Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Berlare Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Beveren Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Brakel Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Buggenhout Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers De Pinte Gent Toon Haezaert Deinze Gent Toon Haezaert Denderleeuw Aalst Karen Jutten Dendermonde Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Destelbergen Gent Toon Haezaert Eeklo Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Erpe-Mere Aalst Karen Jutten Evergem Gent Toon Haezaert Gavere Gent Toon Haezaert Gent Gent Toon Haezaert Geraardsbergen Aalst Karen Jutten Haaltert Aalst Karen Jutten Hamme Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Herzele Aalst Karen Jutten Horebeke Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Kaprijke Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Kluisbergen Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Knesselare Gent Toon Haezaert Kruibeke Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Kruishoutem Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Laarne Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Lebbeke Dendermonde Karolien Rottiers Lede Aalst Karen Jutten Lierde Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Lochristi Gent Toon Haezaert Lokeren Sint-Niklaas Karen Jutten Lovendegem Gent Toon Haezaert Maarkedal Oudenaarde Karen Jutten Maldegem Eeklo Karolien Rottiers Melle Gent Toon Haezaert Merelbeke Gent Toon Haezaert Moerbeke-Waas Gent Toon Haezaert Nazareth Gent Toon Haezaert Nevele Gent Toon Haezaert -

Daguitstappen in Oost-Vlaanderen Verklaring Iconen Gratis

gratis & betaalbare daguitstappen in Oost-Vlaanderen Verklaring iconen gratis parkeren & betaalbare picknick daguitstappen eten en drinken in Oost-Vlaanderen speeltuin toegankelijk voor rolstoelgebruikers Deze brochure bundelt het gratis of op z’n minst betaalbaar vrijetijdsaanbod van het Provinciebestuur. Een reisgids die het mogelijk maakt om een uitstap naar een provinciaal uitstap naar natuur en bos domein, centrum of erfgoedsite te plannen. uitstappen met sport en doe-activiteiten De brochure laat je toe om in te schatten hoeveel een daguitstap naar een provinciaal domein of erfgoedsite kost. culturele uitstap Maar ook of het domein vlot bereikbaar is met de auto, het openbaar vervoer of voor personen met een beperking. De brochure is geschreven in vlot leesbare taal. De Provincie stapt af van de typische ambtenarentaal en ruilt lange teksten in voor symbolen, foto's of opsommingen. Op die manier maakt de Provincie vrije tijd en vakantie toegankelijk voor iedereen! 1 Aarzel dus niet om een kijkje te nemen in deze brochure en ontdek ons mooi aanbod. Colofon Deze publicatie is een initiatief van de directie Wonen en Mondiale Solidariteit van het Provinciebestuur Oost-Vlaanderen en het resultaat van een vruchtbare samenwerking tussen de dienst Communicatie, dienst Mobiliteit, directie Sport & Recreatie, directie Leefmilieu, directie Economie, directie Erfgoed en Toerisme Oost-Vlaanderen. Samenstelling Eindredactie: directie Wonen en Mondiale Solidariteit: Laurence Boelens, Melissa Van den Berghe en David Talloen Vormgeving: dienst Communicatie Uitgegeven door de deputatie van de Provincie Oost-Vlaanderen. Beleidsverantwoordelijke: gedeputeerde Leentje Grillaert Verantwoordelijke uitgever: Leentje Grillaert, gedeputeerde, p/a Gouvernementstraat 1, 9000 Gent Juni 2019 D/2019/5319/5 #maakhetmee Waar in Oost-Vlaanderen? Inhoud Hoe lees je de brochure? ..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

De Versterkingen Van De Wellingtonbarriere' in Oost-Vlaanderen

DE VERSTERKINGEN VAN DE WELLINGTONBARRIERE' IN OOST-VLAANDEREN DE VESTING DENDERMONDE, DE GENTSE CITADEL EN DE VESTING OUDENAARDE ROBERT GILS GENT 2005 DE VERSTERKINGEN VAN DE WELLINGTONBARRIERE' IN OOST-VLAANDEREN DE VEST! G DENDERMONDE, DE GE TSE CITA DEL EN DE VESTING OUDENAARDE ROBERT GILS GENT 2005 INLEIDING Wanneer Napoleon in 1815 van het toneel verdwijnt, lijkt er voor Ew·opa een nieuwe tijd aan te bi-eken. De grote mo gendheden nemen het besluit de beide Nederlanden te vei- enigen onder het Huis van Oranje. Tussen 1815 en 18l0, tijdens die kortstondige hereniging, bouwt of vernieuwt de ederla.ndse genie, op het grond gebied van het huidige België, 19 vestingen als grensverde diging tegen Frankrijk: de Wellingronbarrière. Drie van die vestingen lagen op het grondgebied van de provincie Oost Vlaanderen, namelijk Dendern10nde, Gent en Oudenaarde. Deze publicatie schetst de tomandkom.i.ngvan de Welling ton barrière en beschrijft de ,-ersterkingen van die drie Oost-Vlaamse steden, alsook de vestingbouwkundige over blijfselen ervan. DE WELLINGTON ' BARRIERE EEN BARRIÈ RE Grensversrerkingen behoorden tot de zogenaamde strate gische versterkingen. Ze moesten nier alleen een object ver dedigen, zoals een woning of een nederzetting, maar een hele streek of zelfs een land en maakten dus deel uit van de nationale landsverdediging. De uitbouw van dergelijke ,·er srerkingen was maar mogelijk wanneer her centraal bestuur sterk genoeg was om zijn wil op re leggen, zoals dar het geval was voor de Romeinen, de graven van Vlaanderen of Ka.rel V. Grensversrerkingen bestonden uit één of meerdere lij nen van forten of vestingen (dit zijn versterkte steden), uit verdedigingslinies of uit een combinatie van beide voor gaande. -

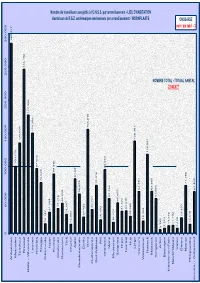

Nombre De Travailleurs Assujettis À L'o.N.S.S. Par Arrondissement - LIEU D'habitation Aantal Aan De R.S.Z

0 50.000 100.000 150.000 200.000 250.000 300.000 Antwerpen 285.317 Mechelen 100.713 Turnhout 135.601 Brussel 246.196 Halle - Vilvoorde 177.566 Leuven 150.259 Nivelles 97.005 Brugge 76.029 Diksmuide 14.147 Ieper 31.594 Nombre detravailleursassujettisàl'O.N.S.S.pararrondissement-LIEUD'HABITATION Aantal aandeR.S.Z.onderworpenwerknemersperarrondissement-WOONPLAATS Kortrijk 89.016 Oostende 37.216 Roeselare 45.028 Tielt 28.247 Veurne 13.584 Aalst 81.681 Dendermonde 58.979 Eeklo 24.422 Gent 156.016 Oudenaarde 35.701 Sint-Niklaas 72.016 Ath 20.100 Charleroi 95.653 Mons 52.166 Mouscron 16.414 Soignies 45.607 Thuin 32.872 Tournai 33.570 Huy 25.280 Liège 138.301 Verviers 62.751 Waremme 18.308 Hasselt 118.531 Maaseik 62.885 NOMBRE TOTAL-TOTAALAANTAL Tongeren 51.994 Arlon 5.369 Bastogne 7.373 Marche-en-Fam 11.275 2.945.077 Neufchâteau 11.792 voir /zietabI-3 Virton 7.419 ONSS-RSZ Dinant 23.320 Namur 71.786 Philippeville 13.519 Inconnu / Onbekend 62.459 0 100.000 200.000 300.000 400.000 500.000 600.000 700.000 800.000 Antwerpen 372.354 Mechelen 80.255 Turnhout 113.531 Brussel 720.477 Halle - Vilvoorde 179.132 Leuven 101.940 Nivelles 71.474 Brugge 66.492 Diksmuide 8.232 22.337 Ieper Nombre detravailleursassujettisàl'O.N.S.S.pararrondissement-LIEUDETRAVAIL Aantal aandeR.S.Z.onderworpenwerknemersperarrondissement-WERKPLAATS Kortrijk 89.877 Oostende 23.727 Roeselare 48.038 Tielt 26.045 Veurne 11.669 Aalst 38.850 Dendermonde 29.849 Eeklo 10.773 Gent 148.949 Oudenaarde 24.309 Sint-Niklaas 45.822 Ath 10.225 Charleroi 84.326 Mons 32.591 Mouscron 18.774 Soignies -

Wegen, Zones & Grenzen Schaal Kaart N Haltes & Lijnen Stadslijnen Aalst

21 22 27 23 Eksaarde 27 Belsele 95 Bazel WAARSCHOOT Eindhalte HEMIKSEM 21 22 73 73 76 Domein Zwembad 93 56 Wippelgem 23 76 58 54 Eindhalte 99s 69 Sleidinge 1 52 Zaffelare AARTSELAAR 21 21 81 53 54 49 27 TEMSE 35 37 82 21 57 58 97 49 53 67 76 74 Eindhalte 73 54 68 91 98 Steendorp Streeknet Dender49 81 SCHELLE Eindhalte 56 68 Rupelmonde 69 74 78 93 95 73 82 92 Tielrode Daknam 81 82 Elversele 97 99 LOVENDEGEM 1 Evergem Brielken 74 Zeveneken 91 93 95 81 NIEL 68 82 97 98 98 76 78 WAASMUNSTER Hingene Schaal kaart 99 99s Stadslijnen Aalst 99 99s EVERGEM LOKEREN BOOM 1 Erpestraat - ASZ - Station - Oude Abdijstraat 0 1 km Belzele 55s LOCHRISTI 257 BORNEM 2 Erembodegem - Aalst Station - Herdersem Oostakker Weert 98 N 68 Schaal 1/100 000 77 35 78 91 92 252 253 257 Eindhalte3 Aalst Oude Abdijstraat - Station - Nieuwerkerken 68 Ruisbroek 252 253 Wondelgem Meulestede 77 254 4 ASZ - Station - O.L.V.-Ziekenhuis - Hof Zomergem 35 Eindhalte 254 257 ©HEREVinderhoute All rights reserved. HAMME 99 99s 252 Eindhalte 250 260 Streeklijnen Dender 92 Kalfort 13 Geraardsbergen - Lierde - Zottegem 35 Beervelde PUURS Terhagen 36 Zele Station 252 16 Geraardsbergen - Parike - Oudenaarde 35 91 37 257 Oppuurs 253 252 17 Geraardsbergen - Lierde - Oudenaarde 18 Eindhalte 68 Mariakerke 53 20Heindonk Gent Zuid - Melle - (Oosterzele) DESTELBERGEN 77 Moerzeke Mariekerke 253 54 21 Dendermonde - Malderen 68 Liezele GENT ZELE 21 Zottegem - Erwetegem - Ronse (Renaix) Drongen 92 92 260 36 Grembergen WILLEBROEK22 Zottegem - Erwetegem - Flobecq (Vloesberg) - Ronse (Renaix) 36 253 -

Belgium-Luxembourg-7-Preview.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Belgium & Luxembourg Bruges, Ghent & Antwerp & Northwest Belgium Northeast Belgium p83 p142 #_ Brussels p34 Wallonia p183 Luxembourg p243 #_ Mark Elliott, Catherine Le Nevez, Helena Smith, Regis St Louis, Benedict Walker PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to BRUSSELS . 34 ANTWERP Belgium & Luxembourg . 4 Sights . 38 & NORTHEAST Belgium & Luxembourg Tours . .. 60 BELGIUM . 142 Map . 6 Sleeping . 62 Antwerp (Antwerpen) . 144 Belgium & Luxembourg’s Eating . 65 Top 15 . 8 Around Antwerp . 164 Drinking & Nightlife . 71 Westmalle . 164 Need to Know . 16 Entertainment . 76 Turnhout . 165 First Time Shopping . 78 Lier . 167 Belgium & Luxembourg . .. 18 Information . 80 Mechelen . 168 If You Like . 20 Getting There & Away . 81 Leuven . 174 Getting Around . 81 Month by Month . 22 Hageland . 179 Itineraries . 26 Diest . 179 BRUGES, GHENT Hasselt . 179 Travel with Children . 29 & NORTHWEST Haspengouw . 180 Regions at a Glance . .. 31 BELGIUM . 83 Tienen . 180 Bruges . 85 Zoutleeuw . 180 Damme . 103 ALEKSEI VELIZHANIN / SHUTTERSTOCK © SHUTTERSTOCK / VELIZHANIN ALEKSEI Sint-Truiden . 180 Belgian Coast . 103 Tongeren . 181 Knokke-Heist . 103 De Haan . 105 Bredene . 106 WALLONIA . 183 Zeebrugge & Western Wallonia . 186 Lissewege . 106 Tournai . 186 Ostend (Oostende) . 106 Pipaix . 190 Nieuwpoort . 111 Aubechies . 190 Oostduinkerke . 111 Ath . 190 De Panne . 112 Lessines . 191 GALERIES ST-HUBERT, Beer Country . 113 Enghien . 191 BRUSSELS P38 Veurne . 113 Mons . 191 Diksmuide . 114 Binche . 195 MISTERVLAD / HUTTERSTOCK © HUTTERSTOCK / MISTERVLAD Poperinge . 114 Nivelles . 196 Ypres (Ieper) . 116 Waterloo Ypres Salient . 120 Battlefield . 197 Kortrijk . 123 Louvain-la-Neuve . 199 Oudenaarde . 125 Charleroi . 199 Geraardsbergen . 127 Thuin . 201 Ghent . 128 Aulne . 201 BRABO FOUNTAIN, ANTWERP P145 Contents UNDERSTAND Belgium & Luxembourg Today . -

Alumni Association

bottom) ( The Ghent Altarpiece Alumni Association Back cover: Dutch countryside (top); detail of Front cover: Bruges. Holland & Belgium Amsterdam to Bruges Aboard Magnifique IV May 26–June 3, 2021 Alumni Association Dear Vanderbilt Alumni and Friends, In Spring 2021, join us on a cultural cruise through the meandering waterways of the Low Countries. Cruise from the Dutch capital of Amsterdam to the medieval city of Bruges in Belgium aboard Magnifique IV, a riverboat ideal for viewing the region’s charming landscapes and historic sites. Begin in Amsterdam and enjoy a visit to the Rijksmuseum, the State Treasury of Dutch paintings. Embark Magnifique IV, a boutique river vessel with just 18 contemporary cabins, for a seven-night cruise through storybook villages and idyllic countryside. In picturesque Kinderdijk, view impressive windmills at a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and continue to historic Dordrecht, stopping to see the Great Church, the Dordrecht Museum, and a medieval monastery. Explore the Belgian cities of Antwerp, where you will visit the Rubens House, and Dendermonde, known for its spectacular Flemish buildings. Call at Ghent for a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity: be among the first to behold Jan van Eyck’s newly restored Ghent Altarpiece in its original home, Saint Bavo’s Cathedral. Conclude among the canals, cobblestones, and medieval buildings of charming Bruges. There, visit the Groeninge Museum for works by Jan van Eyck and other great Flemish artists, see Michelangelo’s Madonna and Child in the Church of Our Lady, and meet a local artist. This delightful journey provides numerous opportunities for cycling, walking, or cruising to CRUISE HIGHLIGHTS view the historic sites and serene landscapes of the region. -

New Light on Old Data : a Neolithic (?) Antler Workshop in Dendermonde (Belgium, O.Vl.)

NotaeA Neolithic Praehistoricae (?) antler 17-1997 Workshop : 199-202 in Dendermonde (Belgium, O.Vl.) 199 New Light on Old Data : a Neolithic (?) Antler Workshop in Dendermonde (Belgium, O.Vl.) Christian CASSEYAS Résumé where the river Schelde has been widen (fig. 1). The Une collection de bois de cerf dragués provenant de Termonde ensemble belongs as well to the prehistoric, roman as montre tous les stades de la fabrication de haches-marteaux à to the medieval period, and there were no indications partir du bois de cerf jusquaux produits finis. Le propos de dater on the field to separate this material. le tout dans le Néolithique sera contrôlé avec des datations AMS. In spite of the small illustrations accompanying his article, it was possible for us to confirm the existence of the collection in the museums depot. Blomme is 1. Introduction referring to 30 antler mattocks, while we only found 5 in the collection. So, a part of the collection must be In 1899, A. Blomme published an article concerning elsewhere or may be lost. Apart from that, the mu- archaeological findings collected after dredging in seum owns a large number of antlers, of which many Dendermonde at the new bridge and at the place are showing traces of working. Fig. 1 Localisation of the place of finding. 200 C. Casseyas 2. The fabrication of antler mattocks to recognize them as well for the simple reason that they constitute the missing parts of the mattocks. Five of the seven implements belong to the antler- The examination of the mattocks and the waste mate- beam mattock type (middenspitsbijlen, haches-marteaux rial, made possible to reconstruct their manufacture as (partie médiane) or Tüllengeheihäxte). -

V.O. Liège - Route

V.O. Liège - route By car Liège Science Park Rue Bois Saint-Jean 29 Coming from Brussels (E40), Antwerp Coming from Maastricht (A25) 4102 OUGREE (E313) or Wallonia (E42) • In the extension of the A25, below Liège, T +32 4 228 05 03 • Coming from Brussels (E40) or Antwerp take the N90 southwards. You drive (E313), follow the direction Namen (E42). along the bank of the river Meuse. Next, follow the direction Seraing-Grâce- • About 10 km south of Liège, the N90 Hollogne to reach the A604. moves away from the river bank and here • Coming from the E42 (l’autoroute de the N680 (Route de Condroz) branches Wallonie), take the A604 via the direction off rightwards from the N90. Liège Seraing-Grâce-Hollogne (after exit No. 3 Science Park is signposted here. of Bierset). • After 5 km turn to the right, into Avenue • Just before the end of that A604, take du Pré Aily. After about 1 km , this road exit No. 4 Liège-Huy-Jemeppe (N617). changes into Rue du Bois Saint Jean. At the traffic light, turn left (direction • After 1 km you pass Rue de Sart-Tilman Liège). De river Meuse is now on your on your right. Our office is located 150 m right. Keep following this road until you further, on your right. can cross the bridge ‘Pont d’Ougrée’ • When you leave V.O., you preferably drive on your right. This is the direction in leftward direction (the building is ‘Université du Sart Tilman Marche - located behind you). At the end of the Dinant (N63)’. -

Vzw Golfbiljartverbond Gent- Eeklo- Oudenaarde-Zottegem Ondernemingsnummer: 044.333.4342 RPR Rechtbank Van Koophandel Gent 0479

Vzw Golfbiljartverbond Gent- Eeklo- Oudenaarde-Zottegem Ondernemingsnummer: 044.333.4342 RPR Rechtbank van koophandel Gent VERSLAG VERGADERING van het Bestuur vzw GEOZ d.d. 10/08/2019 Ref. DC2019-08vzwGEOZ Aanwezigen : Peter , Steven , Xavier , Ronny en Didier. Afwezig ( verontschuldigd ) Jean Paul. Verslag vorige vergadering Is goedgekeurd en op de site geplaatst . Financieel overzicht . De kastoestand wordt besproken en goedgekeurd . Terugbetaling sportpremie. Er zal , op de AV , uitleg gegeven worden aan de leden hoe ze hun lidgeld kunnen recupereren via hun ziekenfonds . Registreren bij BLOSO , formulieren via mutualiteit en de clubs tekenen af. Innerlijk reglement De aanpassingen van het intern reglement worden goedgekeurd door het Bestuur mits volgende opmerkingen: - Minnelijke schikking: afwezig op AV => 25euro - De regel van meeste ploegen in hoogste afdeling wordt aangepast. Deze aanpassingen worden nog opgenomen Klachtenprocedure Steven licht de aanpassingen toe van de klachtenprocedure. Het Bestuur keurt de aanpassingen goed. 0479/535.372 [email protected] https://new-geoz.be Tuinwijk 12, 9870 Machelen a/d Leie Vzw Golfbiljartverbond Gent-Eeklo- Oudenaarde-Zelzate Ondernemingsnummer: 044.333.4342 RPR Rechtbank van koophandel Gent Voorbereiding kalendervergadering: 14u. : Vierde = Ronny ; 14u45 : Derde = Peter ; 15u30 : Tweede = Didier ; 16u15 : Eerste = Peter. Kleine problemen ( dag , uur ) worden onmiddellijk , in overleg , opgelost. Grotere problemen ( geen datum ) wordt , indien mogelijk , opgelost door de kalenderverantwoordelijke Ook de bekerwedstrijden worden definitief geplaatst. Voorbereiding Algemene Vergadering van 17 aug. Om 14 uur te Lotenhulle . - Aanwezigen ( nieuwe werkende leden ) ( Didier ) Afwezig op de AV = Minnelijke schikking van 25 €. - Welkomswoord ( Jean Paul ) - - Financieel ( Steven ) Zoals afgesproken op de vorige AV is de volledige boekhouding , ter controle , verstuurd naar een werkend lid (Freddy Cooreman) . -

Wedstrijdboekje 9 Weekend 8-9 December 2018

o hoofdsponsors /-\'r UNil INTIRET w Oond.tño¡d.. tlõhÍl¡1.¡. sElzoEN 201 g r 201 g Velclenran Wedstrijdboekje 9 Veta tNlEgt€uR MqlNAAM DM TvpklSå'lån'n ['¡cttà- Weekend sìd IOHAN IYBTIRT 8 9 december 201 8 w Ürbidi 1,¡: j.t | ). ; :....¡. û..,h sponsors l\ {) \¡Å i ;.toilstow"8E ßreH nmil¡ffIffilt"ñ.ffiñúbqDHdFb :.p i./ .- .--.. $Z uE tsdÉ ¿ilxu|rdrr lq ir:: )li.i li I lì; I ì: K¡nacll{e :-g Thomas dc a Cook Lli i( )¡vi 1: loo ffi rðe¡å|rreqs4 DIÙIARCO ðriffi [ir+i; E!ç#ìFæ y#$,¡Lftår-ft' E äi¡ii:ess {þ crrRoÈnK Vondewolle ¡!IMûî¡JL fl,.r GREMETRGÊtI -A*ij" \{ pa rtne rs -mm8D Bakk€rU Ollvler Cocâ Colô . Môkelaar3kôntoor Frans De Klnder . Juwell€r Moo¡tgat . Junghetnrtch . HVH tulnaðnl€g . Schtppers pet¿r bvbâ Eufotyrc vrn Eetveld€'DlÊnst€nchequ€s D€nder. R€stôurônt 5t Aldegond€ (M¿spelôr€). tftdlum (G€€rt van Ñuffel). Ffltuur Fôblolð Domlnlqlecorbe€l-DLDCconsultlng.Alservlc€.Kl€dlngRoos€o.FlletPur'k€nrR€stôurôntDePlulm.DeRldderGeoffr€y.KTcc(Kâr€lThyseba€¡dt).G|ospor ..Oì,-.'.¡oagÇÇç_!{Qtd/ ".?.& '.1à ,ìo '.oi : IOHAN LYBEERT Accountant Lybeert Johan Parkla an 23 9300 Aalst Tel:053178 96 15 Fax: 053178 53 39 Mob 0475164 43 62 Mail : johan. [email protected] VËldËrnän ÏÜîAALPRüJ ËCTË N VELDEMAN BVBA Bosveld 20,9200 Dendermonde (België) +32 52 21 67 32 i nfo@vel d em a n-bvba . be Bevrijdingslaan 216 9200 Appels - Dendermonde telefoon : 052 20 04 50 fax : 052 21 85 02 e-mail:info(Ðveta.be website:www.veta.be INTER¡EUR Bevrijdingslaan 216 9200 Appels - Dendermonde telefoon : 052 20 04 50 fax : 052 21 85 02 e-mail:info veta.be website:www.veta.be wrnnfire nuÍnrnan Sports nutrition WWW.WCUP.EU MEIRDAM St-Onolfsdijk 12A 9200 Dendermonde MçIRRåM telefoon : 052 21 27 36 fax : 09 330 17 29 D uwd.ur v*rwd,ø e-mail: dend ermond e@m ei rd am .