Presidents, Patronage, and Turkey Farms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guns, Grass, and God's Wrath, Colorado's Budget, Politics, and Elections

Guns, Grass, and God’s Wrath, Colorado’s Budget, Politics, and Elections Michael J. Berry University of Colorado, Denver I. Introduction At the 2014 Democratic Party Assembly, incumbent Governor John Hickenlooper lamented that no “other state in the union . has been through as much as Colorado has in the past couple of years.” His statement was an implicit reference to a number of recent tragedies in the state. Among the most prominent were the 2012 Aurora movie theater shooting, the callous murder of Department of Corrections director Tom Clements in his home in early 2013, and the most dev- astating forest fires and floods to ever hit the state in June and September 2013. Hickenlooper’s statement on the uniqueness of the state, however, could just as easily apply to the state’s politi- cal realm. Colorado received considerable notoriety from the commencement of recreational marijuana sales on January 1, 2014. In a carefully staged photo opportunity, Iraq war veteran, Sean Azzariti, made the first legal recreational marijuana purchase as the state embarked on a grand social ex- periment. The prior year witnessed the first recall elections in state history resulting in the re- moval of two Democratic legislators from office including Senate President John Morse. An ad- ditional state senator facing a strong recall effort resigned under pressure. These highly charged campaigns to remove legislators were in response to the enactment of several controversial gun control laws. The legalization of recreational marijuana and the fight over gun control grabbed the lion’s share of headlines in the state over the past year. -

Chris Hansen, Gardner for Senate General Consultant Date: June 30, 2020 Re: Gardner Set to Face “Hot Mess” Hickenlooper in General Election ______

To: Interested Parties From: Chris Hansen, Gardner for Senate General Consultant Date: June 30, 2020 Re: Gardner set to face “hot mess” Hickenlooper in general election ____________________________________________________________________________ Today is Election Day in Colorado and Senator Cory Gardner will finally have an opponent. Although we fully expect John Hickenlooper to win tonight, he will emerge a bruised and battered candidate. His once-pristine reputation is tarnished. His glass jaw is fully exposed. And we haven't even started yet. John Hickenlooper is the worst candidate in the country One thing is clear, John Hickenlooper is the worst senate candidate in the country - in either party. Not counting his embarrassment of a presidential campaign, this primary was the first significant challenge in his political career and it was a complete disaster, requiring a multi-million dollar bailout in the form of a flood of last-minute ads from Chuck Schumer to prop him up. Just look at the last 30 days of headlines for Chuck Schumer’s number one recruit: ● AP NEWS: ‘A hot mess’: Hickenlooper stumbles into Democratic primary ● CO SUN: John Hickenlooper apologizes for 2014 “ancient slave ship” comment ● THE HILL: '#DropOutHick': Outcry from Indigenous women, allies over Hickenlooper in red face ● CPR: ‘Disrespect For The Rule Of Law’: Colorado Ethics Commission Holds Hickenlooper In Contempt For Skipping Hearing ● DENVER POST: John Hickenlooper violated ethics laws twice in 2018, commission finds ● CBS4 DENVER: Corporate Donations To Colorado Governor’s Office Raise ‘All Sorts Of Red Flags’ ● NPR: 1 Of Democrats' Top Senate Recruits Stumbles Amid Protests Recall that this primary was the easy path for Hickenlooper. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks at a Democratic

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Remarks at a Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee Lunch in Denver, Colorado July 9, 2014 Thank you, everybody. Thank you. Thank you so much. Everybody, have a seat, have a seat. It is good to be back here. [Laughter] I love Colorado, love Denver. Everybody looks good in Denver too. [Laughter] I don't know what it is, the hair or sun, altitude? I don't know. [Laughter] It's just a bunch of good-looking people in Denver, Colorado. [Laughter] We've got some great friends here, and I just want to mention some of them. First of all, nobody has a bigger heart, nobody did better work on behalf of the natural resources of this amazing country of ours, nobody has been a better friend to me than the person who just introduced me. Love him dearly. We came into the Senate together, and our lives have crossed paths ever since, and I'm so very, very proud of him and Hope. So please give Ken Salazar a big round of applause. To Maggie Fox and Tess Udall, thank you for putting up with somebody in politics. [Laughter] That's always rough, but you do it with grace, and we're so grateful to you. To your wonderful former Governor, Bill Ritter, who continues to do great work on behalf of the environment. My dear friend, who was actually on the steering committee for my first race in '08, one of our national board members, Federico Peña, your former mayor. Somebody who helped begin the tradition of great Democratic Senators from Colorado, Gary Hart is here. -

Ova2011 REPORT to the COMMUNITY

2011 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY innovation “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.” – Steve Jobs Inspiring a Diverse Community of vision Leadership to Improve Colorado. Providing Content, Context and Access to Inspire Leaders to Engage in Issues mission Critical to the Region’s Success. · Cooperative, Collaborative Relationships · Inclusivity and Diversity of Perspective values · Dedication to Quality · Commitment to Volunteerism 2011 REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY FROMTHECHAIRANDEXECUTIVEDIRECTOR November, 2011 The past year has been one of many accomplishments for the Denver Metro Chamber Leadership Foundation. As we reflected on 2010-2011, we noticed a thread that was woven throughout all of our programs—the thread of energetic innovation. The late Steve Jobs, former CEO and co- founder of Apple, is quoted as saying, “Innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower.” In order for the Leadership Foundation to effectively carry out its mission of providing content, context and access to inspire leadership, it has made innovation a top priority, taking the initiative to introduce new programs, processes and content that broaden our perspective, provide an even stronger platform for dialogue and elevate our overall effectiveness at inspiring and educating our community’s leaders. One of the year’s brightest highlights was the launch of Colorado Experience’s pilot program. For many years, the Leadership Foundation has imagined bringing the Leadership Exchange program to a local level, and it was thanks to the strong support of our board of directors and hard work of the Colorado Experience committee that we made this vision into a reality with a trip to Colorado Springs. -

Senator Mark Udall (D) – First Term

CBHC Lunchtime Webinar – Preparing for the NCCBH Hill Day in Washington, D.C. June 2010 Working together to develop and deliver health resources to Colorado Communities Colorado Specifics • Colorado has almost 80 people attending this year • CBHC is scheduling meetings with all of the members of Congress on your behalf • CBHC will email virtual Hill Day packets this year to all registered participants – These will include individualized agenda’s for Hill Visits • Please register with the National Council on the website: http://www.thenationalcouncil.org/cs/join_us_in_2010 June 29th, 2010—Hyatt Regency Hotel • Opening Breakfast & Check-in-- 8:00-8:30 a.m. • Policy Committee Meeting Morning Session—8:30-11:45 • "National Council Policy Update" - Linda Rosenberg, President and CEO, National Council • "Implementing Healthcare Reform: New Payment Models" - Dale Jarvis, MCPP Consulting • Participant Briefing Lunch-12:00-1:00 p.m. • "The 2010 Elections Outlook" - Charlie Cook, The Cook Political Report--1:00-2:00 p.m. • "Healthcare Reform and the Medicaid Expansion" - Andy Schneider, House Committee on Energy & Commerce 2:00-3:00 p.m. June 29th Hyatt Regency • Public Policy Committee Meetings 3:15-5:00 p.m. Speakers for the afternoon session include: • "CMS Update" - Barbara Edwards, Director, Disabled and Elderly Health Programs Group, Center for Medicaid, CHIP, and Survey and Certification (CMCS), CMS • "Parity Implementation - What You Should Know and Do" - Carol McDaid, Capitol Decisions, Parity Implementation Coalition June 29—Break Out -

The 2010 Senate Landscape Is Almost Evenly Split Down The

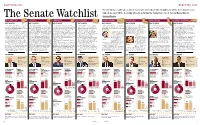

ELECTION 2010 ELECTION 2010 The 2010 Senate landscape is almost evenly split down the middle: Republicans will be defending 18 seats, while Democrats will be defending 19 seats, including the January special election in Massachusetts. The Senate Watchlist BY CHARLES MAHTESIAN CONNECTICUT NEVada ARKANSAS COLORADO PENNSYLVANIA LOUISIANA CALIFORNIA NORTH CAROLINA WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH WHY TO WATCH Chris Dodd, a five-term Democrat, is arguably The only thing stopping Senate Majority Leader In a state where John McCain crushed Barack Democrat Michael Bennet, appointed Democratic Sen. Arlen Specter faces what may Just when it looked like GOP Sen. David Democratic Sen. Barbara Boxer won a There’s no scandal or silver-bullet issue. He’s the party’s most vulnerable Senate incumbent — Harry Reid from being rated as the most vulnerable Obama by 20 points in 2008 and where polls show to the Senate seat left vacant when Ken be the toughest election of his Senate career, Vitter might weather the scandal surrounding second term in 1998 by 10 percentage points reasonably well-funded. And unlike former GOP just look at the lengthy list of Republicans who are Democratic senator is the quality of his opposition. voters are deeply skeptical of Obama’s health care Salazar became interior secretary, has two which is saying something given the long arc of his the revelation that he was a client of a and a third in 2004 by 20 points. colleague Sen. Elizabeth Dole, who lost by a champing at the bit to take him on. -

Official Ballot for Democratic Party Pueblo County Primary Election

Official Ballot for Democratic Party Ballot Type: D46 Pueblo County Primary Election Tuesday, June 30, 2020 Clerk and Recorder Return only one ballot. If your mail ballot packet contains ballots for both the Democratic and Republican Parties, mark and return only one ballot, and destroy the other. If you mark and return both party ballots, neither will count. Please vote your mail ballot. Due to COVID-19, help us make this a safe election for everyone by returning this ballot via mail or drop box. Instructions To vote for a named candidate, completely fill in the oval to To make a correction, draw a bold line through the oval and the left of your choice. Use blue or black ink. candidate name marked by mistake. Then, completely fill in the oval next to the correct name. WARNING: Any person who, by use of force or other means, unduly influences an eligible elector to vote in any particular manner or to refrain from voting, or who falsely makes, alters, forges or counterfeits any mail ballot before or after it has been cast, or who destroys, defaces, mutilates, or tampers with a ballot is subject, upon conviction, to imprisonment, or to a fine, or both. Section 1-7.5-107(3)(b), C.R.S. Federal Offices State Offices County Offices United States Senator State Board of Education Member - County Commissioner - District 1 .(Vote for One) Congressional District 3 .(Vote for One) .(Vote for One) Andrew Romanoff Eppie Griego John W. Hickenlooper Mayling Simpson Tisha Mauro Representative to the 117th United State Representative - District 46 County Commissioner - District 2 States Congress - District 3 .(Vote for One) .(Vote for One) .(Vote for One) SAMPLEDaneya Esgar Garrison Ortiz James Iacino District Attorney - 10th Judicial District Abel Tapia Diane E. -

HOUSE JOURNAL SIXTY-SEVENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE of COLORADO First Regular Session

Page 1 HOUSE JOURNAL SIXTY-SEVENTH GENERAL ASSEMBLY STATE OF COLORADO First Regular Session First Legislative Day Wednesday, January 07, 2009 1 Prayer by James D. Peters, Jr., Retired Pastor, New Hope Baptist 2 Church, Denver. 3 4 The hour of ten o'clock having arrived, the House of Representatives of 5 the Sixty-seventh General Assembly of the State of Colorado, pursuant 6 to law, was called to order by Andrew Romanoff, Speaker of the House 7 of Representatives, Sixty-sixth General Assembly, State of Colorado. 8 9 The Temporary Speaker announced that if there were no objections, 10 Marilyn Eddins would be appointed Temporary Chief Clerk. 11 12 ______________ 13 14 15 STATE OF COLORADO 16 17 Department of 18 State 19 20 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) 21 STATE OF COLORADO ) SS. Certificate 22 23 I, Mike Coffman, Secretary of State of the State of Colorado, do hereby 24 certify that I have canvassed the "Abstract of Votes" submitted in the 25 State of Colorado and do state that, to the best of my knowledge and 26 belief, the attached list represents the votes cast for members of the 27 Colorado State House of Representatives for the Sixty-seventh General 28 Assembly by the qualified electors of the State of Colorado in the 29 November 4, 2008 General Election. 30 31 IN TESTIMONY WHEREOF, I have hereunto set my hand and affixed 32 the Great Seal of the State of Colorado, at the City of Denver this 16th 33 day of December, 2008. 34 35 (Signed) 36 Mike Coffman 37 Secretary of State 38 39 40 _______________ 41 Page 2 House Journal--1st Day--January 07, 2009 1 November 4, 2008 General Election Final Results 2 3 Candidate Vote Totals Percentage 4 5 St. -

2014 Midterm Election Results

2014: Wave or No Wave Nationalization or All Elections are Local or Both President Obama’s Approval Ratings 2012-2014 60% 56% 54% 53% Metrics 52% 51% 48% 50% 50% 49% 50% • Obama spread – (11%) 48% 2014 Midterm Election Results • Congressional approval – 13% 49% 47% 47% • Generic ballot test – Reps 2% 40% 42% 43% 44% 42% 40% • Direction, right – 27% • House 234, need 17/lost 12 30% Colorado Medical Society • Senate 45, need 6/won 8/9 7-Sep-12 4-Nov-14 1st Debate Christmas 15-Apr-13 29-Nov-13 20-May-14 Elec9on Day Inauguraon Approval Disapproval Source: Real Clear Politics 2013/14 Floyd Ciruli Formatted: Ciruli Associates 2014 184 44 244 53 November 2014 House Minority Leader Senate Majority Leader Speaker Senator Nancy Pelosi Harry Reid John Boehner Mitch McConnell Ciruli Associates 1115 Grant St., Ste G-6 Denver, CO 80203 PH (303) 399-3173 FAX (303) 399-3147 www.ciruli.com 1 Ciruli Associates 2014 Control of U.S. Senate 2014 Tonight You Shook Up the Senate Forecasts Mostly Right; Miss Size of Republican Tide Gardner by 2 Points and Wins by 2; Post Endorses Montana November 4 and Results New Hampshire R-18 (18) South Dakota D-1 (4) Iowa R-11 (20) R-2 (8) Gardner vs. Udall – Real Clear Politics “Abut 85 percent Poll Date Gardner Udall of Colorado voters Results 11-4 48% 46% immediately Average 11-2 46 44 Kentucky R-7 (15) decided who they PPP 11-2 48 45 supported. Since Quinnipiac 11-2 45 43 then, the lead has West Virginia Denver Post 10-29 46 44 Sen. -

Salazar's Behalf Said That the First-Term Senator Sources: Salazar Interviewed for the Position Last Week and Is All but Certain to Be Appointed to Obama's Cabinet

http://www.denverpost.com/fdcp?1231537726147 denver and the west Democratic sources who asked not to be named because they were not authorized to speak on Salazar's behalf said that the first-term senator Sources: Salazar interviewed for the position last week and is all but certain to be appointed to Obama's Cabinet. accepts Interior post Speaking to the media in Chicago on Monday, Obama said he would name the interior secretary later this week. By Christopher N. Osher and Karen E. Crummy Salazar's pending selection was revealed on the The Denver Post same day Denver Public Schools Superintendent Michael Bennet learned that he would not be offered Posted: 12/16/2008 12:30:00 AM MST the job of education secretary. Also Updated: 12/16/2008 12:32:22 PM MST Senate Seat Discuss who you think Gov. Ritter should name to replace Ken Salazar in the U.S. Senate. Monday, sources close to Denver Mayor John Hickenlooper said he is among several candidates to be transportation secretary in the Obama administration. Salazar met with members of Obama's transition team in Chicago at the end of last week to discuss a possible appointment to the Interior Department post, sources close to the transition team said. The position has not been formally offered, but no other candidates are known to be undergoing the Barack Obama leads a get-out-the-vote Rally for Colorado 7th Congression requisite background checks, and multiple sources candidate Ed Perlmutter in Aurora in October, 2006. U.S. Sen. Ken Salazar (THE DENVER POST | KATHRYN OSLER) said Salazar has signaled his willingness to give up his Senate seat for the job. -

2015 Conference Program

Connect. Collaborate. Colorado-style. 2015 Fifty, Five and the Future As Medicaid Turns 50 and the Affordable Care Act Turns Five, What’s Next for Health Policy in Colorado? KEYNOTE SPEAKER: Dr. Alice Rivlin Dr. Alice Rivlin is the Director of the Health Policy Center Studies Program at Brookings. Dr. Rivlin is the recipient at the Brookings Institution and the Leonard D. Schaeffer of numerous awards, including a MacArthur Foundation Chair in Health Policy. She is also a senior fellow in the “genius grant.” Economic Studies Program at Brookings and a visiting professor at the McCourt School of Public Policy at Originally from Philadelphia, she received a B.A. in Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. economics from Bryn Mawr College and a Ph.D. from Radcliffe College (Harvard University) in economics. She founded the Congressional Budget Office, which Dr. Rivlin continues to be a frequent contributor to provides nonpartisan budgetary and economic research, discussion and federal testimony around health information to support the federal budget process, in insurance in the United States. 1975. She has also served as Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve Board, Director of the White House Office of We are pleased to have her join us as the Keynote Management and Budget, and Director of the Economic Speaker for Hot Issues in Health Care 2015. #HIHC15 CONFERENCE AGENDA 11:50 a.m. Morning Breakout Sessions II (Choose One) 8:00 a.m. – 9:00 a.m. Registration and Buffet Breakfast Markets Under Pressure: How We Got Here and What’s Next Outside of Summit Ballroom Senior Director for Policy and Analysis Amy Downs and Research Analyst Tamara Keeney, 9:00 a.m. -

PROCEEDINGS Institute of Politics

1990-91 1991-92 Institute of Politics Jnliii i}\ KeHHech- School of Gcivernnient Harvard University PROCEEDINGS Institute of Politics 1990-91 1991-92 John R Kennedy School of Government Harvard University FOREWORD The Institute of Politics continues to participate in the democratic process with the many and varied programs it sponsors: a fellows program for individuals from the world of politics and ihe media; a program for undergraduate and graduate students encouraging them to become involved in the practical aspects of politics; training programs for elected officials including newly-elected members of Congress and newly-elected mayors; a variety of conferences and seminars; and a dynamic public events series of speakers and panel discussions in the Forum of Public Affairs of the John F. Kennedy School of Government. This edition of Proceedings, the thirteenth, covers two academic years—1990-91 and 1991-92—and shows the range of activities through which the Institute addressed the major political issues and events of the day, from the war in the Persian Gulf to the 1992 presidential election. The Readings section provides a glimpse at some of the actors involved and the issues discussed. The Programs section provides details of the many undertakings of the student program—study groups, twice-weekly suppers, intern ships, summer research grants, the quarterly Harvard Political Review, political debates and many special projects. There is also information on the program for fellows, on conferences, seminars and meetings, and a list of events held in ttie Forum. On October 25 and 26, 1991, the Institute celebrated the 25th anniversary of its founding with an exciting schedule of events including a traditional lOP supper, a debate between Ron Brown and Clayton Yeutter, chairmen of the Democratic and Republican National Committees and a 1960s dance.